Chapter 40 Open Debridement and Interposition

Introduction

The many causes

Degenerative conditions of the elbow have a broad spectrum of pathology: primary osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthropathies, posttraumatic arthritis, osteochondritis dissecans and degenerative changes from instability. Furthermore conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis have their own spectrum of pathology – those who mainly present with deranged mechanics and those patients whose primary complaint is pain.1 Published results rarely discriminate between these causes, so there is limited evidence as to which are best treated with open debridement. Moreover, knowing the aetiology of the arthropathy does not predict the exact cause of the pain and stiffness. Degenerative changes of the bone or soft tissues affect any part of the complex elbow joint, so it is better to determine the anatomical cause of the patient’s pain and stiffness. Only then can it can be accurately addressed at the time of surgery.

Background/aetiology

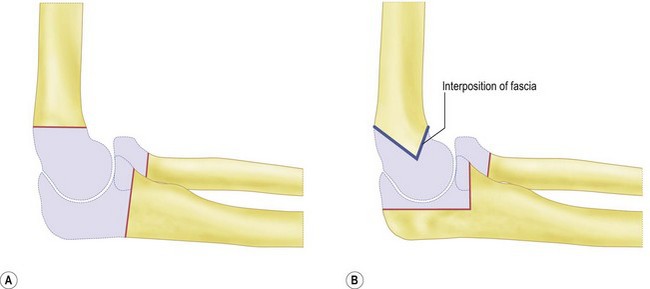

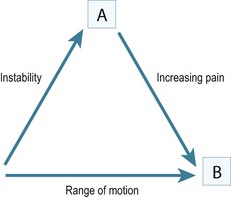

Historically the treatment for painful elbow ankylosis was a resection arthroplasty; resection of the painful joint was achieved by excising the entire olecranon, radial head and distal humerus above the condyles (Fig. 40.1A). Whilst in most cases this gave good pain relief, instability was common as there were no soft tissue or bony stabilizers remaining after surgery. Stability relied purely on the fibrous scar tissue between the cut bone surfaces. Despite this, good results were reported in posttraumatic, tuberculosis and rheumatoid arthrirtis.2–4 Defontaine introduced the interposition as a refinement to the resection arthroplasty in 1887.5 By removing less bone and leaving a fulcrum between the olecranon and the distal humerus, he addressed the difficulty of instability experienced in resection arthroplasty (Fig. 40.1B). Tissue was positioned in the joint to act as a spacer, keeping the collateral ligaments functional and providing a pain-free articulation. The material used was varied and included muscle transposition, skin, fat or even pig’s bladder. Despite the use of an interposition graft, however, because less bone was excised, stiffness and even reankylosis could still be a problem. Hass cut the distal humerus into a wedge with the idea of reducing bone contact while still providing a fulcrum, however, pain, stiffness and wear of the articulation remained a persistent problem.6 Schüller first published the use of interposition in rheumatoid elbows in 1893. Hurri et al reported on 76 rheumatoid elbows and found that interposition arthroplasty provided better stability compared with the group of patients who had had a resection arthroplasty alone.3 However, their results also showed that only 40% were pain-free compared with 64% in the resection group. These were also the findings of Buzby, who concluded that patients were happier with a pain-free, flail elbow than they were with the more stable but painful interposition arthroplasty, the surgery often providing only a few degrees of extra motion.2 Even in these early reports it became clear that movement was always achieved at the expense of stability, while movement with stability resulted in less predictable pain relief (Fig. 40.2).4

In 1971, Peterson and Janes published the experience from the Mayo clinic, which identified a spectrum of pathology in the rheumatoid elbow; those with deranged mechanics and those patients whose primary complaint was pain.1 In patients whose primary complaint was pain, a limited open debridement, synovectomy with radial head excision produced better results than interposition. The use of interposition arthroplasty has declined with the increasing success of total elbow arthroplasty, which gives better pain-free range of motion and stability in the low-demand patient.

It was not until the 1970s that Minami7 and Kashiwagi8 published the first papers giving a detailed description and recommended treatment option for less severe elbow osteoarthritis. A procedure first described by Outerbridge and then published by Kashiwagi became known as the Outerbridge–Kashiwagi procedure. In 1992 this was modified by Morrey, who used a trephine to remove osteophytes encroaching on the olecranon and coronoid fossae, with elevation rather than splitting of the triceps, the so-called ulnohumeral arthroplasty.9 The column procedure approached the elbow via a lateral incision, debriding osteophytes and releasing the capsule through both anterior and posterior intervals. A more extensive debridement arthroplasty was described by Tsuge and Mizusek, which involved a formal disarticulation of the joint, with or without release of the collateral ligaments, excision of the capsule and reshaping of the radial head.10

Aetiology of pain stiffness around the elbow

Primary osteoarthritis

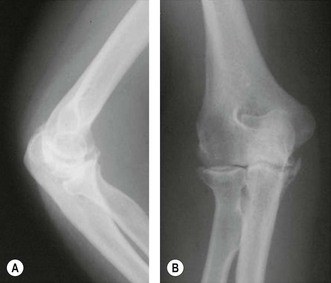

This accounts for only 2–3% of patients presenting with elbow arthritis.11 It seems to almost exclusively affect men who are engaged in repetitive heavy manual labour and is presumably as a result of a genetic predisposition, followed by environmental stimulus for wear. The pathological changes which occur as the disease process progresses have been described.12,13 The elbow forms osteophytes which occur on the coronoid, olecranon and fill their respective fossae on the humerus. Due to the high congruency of the joint, there is an early decrease in the range of movement. Pain can occur where the extra bone growth impinges on neighbouring normal bone or due to the development of a ‘kissing lesion’. The joint space, however, is initially maintained and the ulnohumeral articular cartilage is not worn.10,14,15 It is this characteristic which allows for the successful treatment with debridement of the extrinsic bone and soft tissue, leaving the relatively preserved ulnohumeral articulation alone. Osteophytes can break off and form loose bodies which cause locking as they interpose themselves within the joint. The ulnar nerve can also be irritated by the degenerative processes within the elbow and can often be a leading source of pain. Finally, ulnohumeral articular wear develops; this tends to cause pain which persists throughout the entire range of motion. Removal of osteophytes and soft tissue release will be less successful in these patients, as the ulnohumeral joint has intrinsic wear.

Heterotopic ossification

This is new bone formation within non-osseous tissues typically after elbow dislocation, with an incidence varying from 25% to 75%.12,16 This high incidence is thought to be as a result of brachialis, which is mainly muscular as it crosses the joint, being torn at the time of dislocation. It also occurs after surgery and its incidence is increased in the presence of a concomitant head injury.

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

History

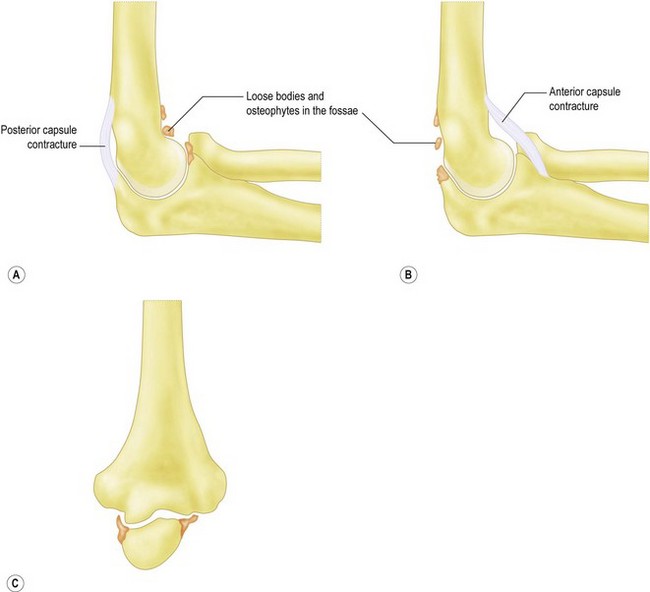

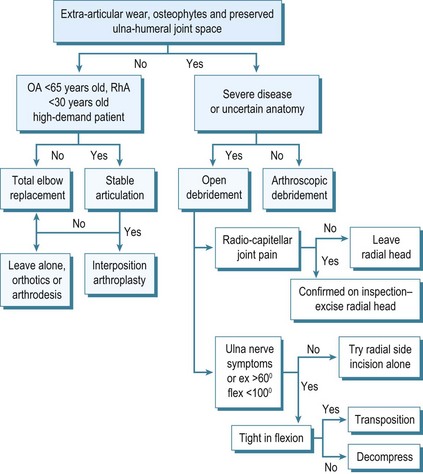

The patient’s age and occupation is important. Find out why the patient has consented to treatment. While most patients will complain of both pain and loss of movement, one is often more of a problem than the other. Is the loss to range of movement functionally significant? Does it stop them doing their job? If so, document whether it is flexion or extension which is the main limiting factor. This will guide you into which soft tissues or bone needs to be debrided to give the elbow a functional range of movement (Fig. 40.3). Can the patient reduce the demands on the elbow or even change jobs?

Clinical examination

Is pain limited to the endpoint of movement, suggesting impingement due to osteophytes which can be removed? Or, is it throughout the arc of movement, suggesting intra-articular wear, which is less likely to benefit from joint preserving open debridement (Fig. 40.4). Does the endpoint have a solid, bony block to it, or is it soft and springy, which would suggest a soft tissue contracture.

Trauma and instability

Accurate examination of the lateral and medial collateral ligaments is difficult; however, any gross instability should be assessed. In cases of trauma, non-union and malunion should be identified, as these may require fixation and bone grafting at surgery. In posttraumatic cases where the anatomy may have been altered, arthroscopic debridement carries a high risk of an iatrogenic injury to neurovascular structures.17

Investigation

Ultimately the decision to perform debridement is based on the disease process, anatomical culprit of the pain and stiffness, patient and surgeon factors. Table 40.1 summarizes the factors which the surgeon should consider in the management of elbow arthritis.

| Patient factors | Age |

| Activity level | |

| Willingness to modify activity level | |

| Poor rehabilitation potential | |

| Anatomical factors | Articular wear |

| Impingement spurs | |

| Loose bodies | |

| Ulna nerve symptoms | |

| Soft tissue contracture | |

| Stability | |

| Disease factors | Primary osteoarthritis |

| Inflammatory arthritis | |

| Trauma | |

| OCD in young patient | |

| Athletes | |

| Surgeon factors | Training |

| Experience | |

| Technical expertise |

Treatment options

While total joint replacement has been adopted as the treatment of choice in most other joints of the body, the role of total elbow replacement in degenerative conditions at the elbow remains limited. Kozak reported complications in four out of five elbow replacements for primary osteoarthritis at 3 years.18 In addition, elbow arthritis again largely affects middle-aged men in manual work who wish to maintain their high demands on the elbow joint; they are obviously not good candidates for arthroplasty.9

Surgical debridement serves to remove painful osteophytes which impinge causing pain and loss of movement, along with a release of soft tissues to improve movement. This is only effective in patients with relatively well-preserved ulnohumeral cartilage. If there is excessive wear and joint-space narrowing the elbow will continue to be painful and total elbow arthroplasty or interposition arthroplasty would be the better option. Various techniques to debride the elbow can now be undertaken arthroscopically. Recent advances in arthroscopic surgery to the elbow have meant many patients with less severe arthritis can be treated in this way. However, it is contraindicated in the presence of extensive osteophytes, multiple pathology, previous surgery and uncertain anatomy. While there may have been some excellent reported outcomes, arthroscopic debridement is regarded by many surgeons as having an increased risk of complications,19–23 with no clear clinical benefit over open surgery.24,25 Open debridement of the elbow remains the mainstay of treatment for moderate to severe elbow arthritis.

Contraindications for open debridement

The presence of metabolically active heterotopic ossification is a relative contraindication to early open debridement. The optimal timing for excision of the heterotopic ossification has not been established. A normal alkaline phosphatase is useful in patients who have large amounts of heterotopic ossification, typically around the hip. However, a relatively small amount of heterotopic ossification around the elbow results in only a small rise in alkaline phosphatase levels, which makes it an unreliable indicator of osteoblast activity. A three-phase technetium scan has been reported as being 90% sensitive for metabolically active heterotopic ossification and is therefore the preferred method.26 Heterotopic ossification can absorb over time, especially in children who have a recovering head injury. There is some evidence that earlier release is preferable (6 months) as it gives better long-term results.27–29 The use of preoperative radiotherapy and non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs also decreases the risk of recurrence after excision.29

Interposition arthroplasty is an option if the ulnohumeral joint has intra-articular wear and the patient is too young or active for a total elbow replacement. Interposition arthroplasty does not carry the same weight-lifting restriction as total elbow arthroplasty (5 kg lifting or 2 kg repetitive restriction) and has been shown to be durable in the active patient.30,31 Alternatives are limited in these patients; arthrodesis severely limits the functional tasks that can be performed and is poorly tolerated. Resection arthroplasty creates severe disabling instability in most patients and is only indicated in those with active infection. Satisfactory results have been published for interposition arthroplasty in healthy, active patients with severe posttraumatic or rheumatoid elbow arthrosis.30,32–35

This salvage procedure, however, should only be considered when the patient is disabled by pain with loss of function and non-operative measures have been exhausted.35 There is no age limit as a guide, but interposition arthroplasty is typically performed in patients with severe inflammatory arthritis (<30 years old) or posttraumatic arthritis (<60 years old). It is important that the elbow is stable as there is a significant association between poor outcomes and preoperative instability.30,35 For the interposition arthroplasty to have the best results there needs to be both bony congruence and soft tissue stability. The most common contraindication is insufficient bone stock which will increase postoperative instability due to lack of congruency. This can be restored by grafting the distal humerus as a staged procedure. An alternative is to use the calcaneal bone graft attached to the Achilles tendon at the time of surgery. Deformity which alters the mechanical axis of the arm will need to be corrected with an osteotomy if possible, as the pull of the flexors and extensors must be centred over the arthroplasty for stability. Ten degrees of varus or valgus is considered to be the limit. The interposition arthroplasty will not, however, provide prolonged pain-free stability if the patient is involved in very heavy manual labour which requires lifting with abduction of the shoulder. In these patients either a new occupation must be found or rarely an arthrodesis may be a better option. The sustained use of crutches or having to transfer from bed to a chair is also a relative contraindication.

The principle of the surgery is to place scar tissue between the distal humerus and olecranon in place of the articular cartilage. In 1990 Morrey developed three additional features to the technique: distraction using an external fixator, early postoperative motion and a larger interposition graft.36 Various interposition materials have been used in the ulnohumeral joint, including fascia lata,35 cutis graft,37 Achilles tendon allograft,30 Gelfoam38 and silicone.39 The Wrightington experience has been with Achilles tendon allograft, which has the benefit of no donor site morbidity and an adequate thickness without having to suture several layers together. There is some evidence that it may survive longer than fascial interposition graft, leading to fewer patients requiring revision surgery in the early postoperative period.30 The elbow is then held with a dynamic external fixator which is used as a means of initiating early motion while neutralizing forces and thus protecting the soft tissues, the interposed graft, and any ligament repair or reconstruction.31,36

Recent advances: the lateral compartment resurfacing elbow arthroplasty

Summary Box 40.4

Surgical techniques and rehabilitation

Goals of management

Ideally, the arc of movement should be between 30° and 130° of flexion, with 50° of supination and 50° of pronation. This range of motion has been demonstrated to be sufficient for most activities of daily living.9 There is no doubt, however, that the loss of terminal flexion, which is required for bringing the hand towards the face, for feeding and grooming, etc., is a more significant disability than the loss of terminal extension. The second goal should be stability. Stability is more important for patients who do heavy lifting and manual activities, especially when the arm is internally or externally rotated. In this position maximum valgus and varus stresses are applied across the elbow and any instability will be apparent. The third goal is to extinguish pain. If surgery increases the range of motion significantly but the joint is too painful to move, the patient will not regard it as a successful operation.

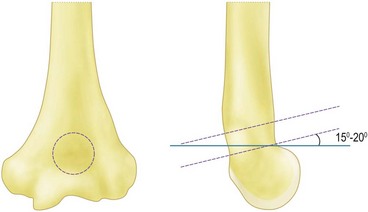

Surgical technique – open debridement

Sufficient exposure is required to accurately place the trephine in the centre of the olecranon fossa. Too distal and the trochlea will be thinned and insufficient bone will be removed to allow the olecranon to engage, too lateral and the trephine will cut into the capitellum as it breaks through on the volar surface and too medial will weaken the thin medial column. Extensive osteophytes and previous debridement can mean that accurate placement is difficult. In this instance it is best to perform a thorough debridement of the olecranon first and then extend the elbow which will then indicate the position of the fossa. The distal humerus flexes as it approaches the elbow, so the trephine should be angled 15–20° proximally front to back to avoid damaging the anterior articular surfaces (Fig. 40.6). Once the volar cortex is cut through the dowel is removed. The fenestration can be widened and the edges smoothed using Cloward up-biting rongeurs, which have the benefit of protecting the volar structures. They can also be used to remove excess bone from the anterior compartment.

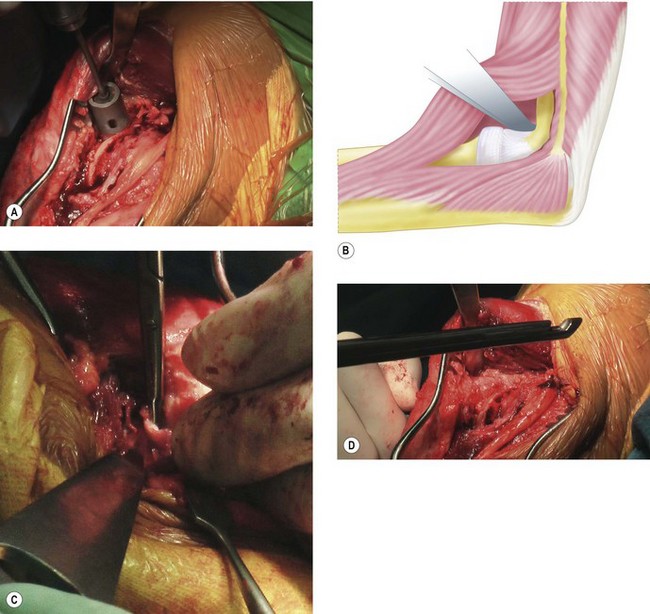

A Homan retractor can be used to lift the brachialis muscle off the capsule giving access across to the medial side, allowing a clear view to excise the entire capsule (Fig. 40.7). Full flexion and extension should now be achieved with gentle short lever arm manipulation. Any bone impingement or soft tissue contracture which may be blocking range of motion can be palpated by placing a finger front and back during flexion and extension. Bone wax can be used to seal the bleeding cancellous bone which is necessarily exposed during the operation. If more than 50% of the triceps has been lifted off the olecranon it must be formally repaired with osseous sutures. The use of a drain will reduce postoperative swelling, particularly if there is a large potential space under the posterior skin flaps.

Surgical technique – interposition arthroplasty

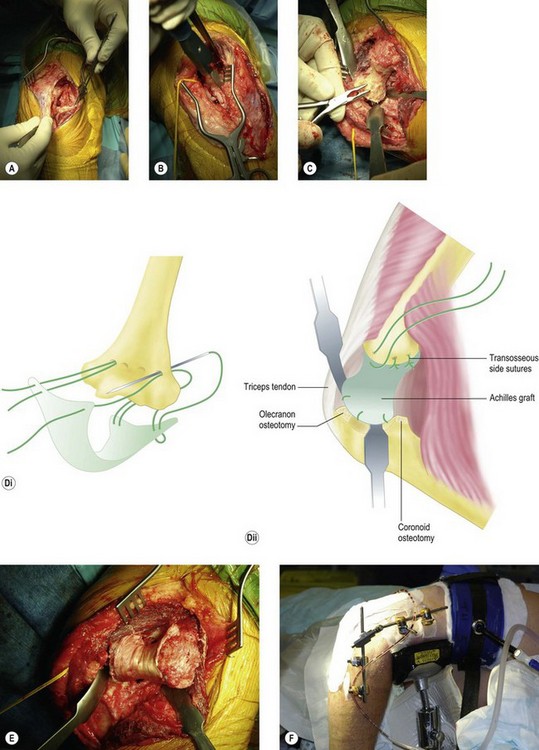

An indwelling catheter is sited to give adequate postoperative pain relief to allow continuous passive range of motion for 24–48 hours postoperatively. The patient is positioned and the incision is made in the same way as that described for the open debridement. If patients have had previous surgery, any scars should be incorporated into the incision to reduce the potential risk of skin necrosis. Once the full thickness skin flaps have been raised both medially and laterally the bony ridge of the ulna is palpated through the fascia. The soft tissue plane between anconeus and extensor carpi ulnaris (Kocher’s interval) can be utilized, although I prefer the interval between the ulna and anconeus. An incision is made 5 mm or so lateral to the ulnar ridge, exposing the anconeus muscle bellow. This 5 mm cuff of tissue allows easy repair of the fascia at the end of the operation. The anconeus is then stripped off the lateral face of the proximal ulna down to the supinator crest where the lateral ligament complex of the elbow inserts. The annular ligament is lifted off the supinator crest using subperiosteal dissection (Fig. 40.8A). If the radial head is still present and requires excision it can be delivered into the wound and removed. At this stage it should be possible to supinate the forearm, lifting the ulna off the trochlea. The articular cartilage can then be clearly visualized to confirm that the ulnohumeral articulation requires an interposition arthroplasty. If more than 50% of the surface is worn then interposition is warranted. Any worn areas should not be confused with the normal absent or thin articular cartilage in the mid-portion of the olecranon. Before proceeding to interposition arthroplasty the lateral side of the distal humerus must be exposed to allow access to the anterior compartment of the elbow. To achieve this, using sharp dissection and sticking close to bone, the anconeus, lateral ulnar collateral ligament and common extensor origin are lifted off as one big sleeve of tissue until it can be folded over the epicondyle. It should now be possible to see the volar capsule, which will need to be released to gain useful elbow motion. Careful dissection of the capsule away from the overlying tissue before excision will protect the posterior interosseous nerve from injury. If there is any doubt as to the safety of this, the capsule can be stripped off the humerus more proximally using a periosteal elevator. This will then allow extension without removing the capsule. However, it is likely that without excision of the capsule the anterior release will be less effective.

Moving to the medial side, the ulnar nerve is identified proximally in normal tissue and dissected out distally. It is then lifted out of its bed so that the ulnar gutter can be approached with safety. If the anterior bundle of the ulnar collateral ligament has not been destroyed by the disease process, it can be clearly demarcated and protected as it is vital for postoperative stability. While leaving it attached makes the exposure for the rest of the operation more difficult, I believe it should be protected because instability is a leading cause of failure. The remainder of the medial ligament and scar tissue is removed from the ulnar gutter along with any excess bone in the olecranon fossa. The triceps can be lifted off the distal humerus with a retractor. There are usually large osteophytes here, partly due to the posteromedial impingement found in valgus laxity, and also because they are often left over after previous debridement, as they lie under the nerve and near the anterior ligament. These osteophytes along with the tip of the olecranon should be excised; this will aid in dislocation of the joint (Fig. 40.8B). The articular surfaces are then fully exposed.

The next step is to prepare the bone of the trochlea and olecranon. The aim is to have a smooth articulation of subchondral bone between the trochlea and the olecranon, leaving a 3 mm gap between the two to accommodate the graft. If too much bone is removed, this will result in increased wear. Alternatively, if there are any ridges there will be poor congruence and if sclerotic bone is left the graft will not adhere onto the trochlea (Fig. 40.8C). Using the technique described by Cheung and Morrey,35 three or four drill holes are made from posterior to anterior across the distal humerus at the proximal edge of the articulation. Horizontal mattress sutures are passed through the Achilles graft and then the drill holes, with further sutures passed through the bone at the edges (Figs 40.8D and E). The joint is reduced and checked for range of motion and congruence. The lateral soft tissues are sutured to the lateral condyle and the annular ligament fixed back to the supinator crest with transosseous sutures. The range of motion is checked once more. Some elbows are stable and in these cases an external fixator is not essential, however, the fixator also distracts the joint, maintaining the gap while the graft integrates with the bone. For this reason we prefer to apply an external fixator in all cases (Fig. 40.8F).

Rehabilitation

The formation of postoperative scar tissue (which can develop into contracture if left static) has three phases and an understanding of this will help with its management. In the inflammatory phase scar tissue forms from postoperative bleeding and oedema, which must be minimized. Postoperative bleeding is reduced by meticulous haemostasis prior to closure and the use of drains. Bone wax can reduce osseous bleeding, however, it introduces a foreign material which will create its own inflammatory reaction and increase the risk of infection.40 Bleeding can be further reduced in the immediate postoperative period by applying a light compression bandage and elevating the arm with the elbow extended. The wounds should be dressed with a sterile non-adherent dressing and bulk must be kept to a minimum. The use of cryotherapy to reduce oedema also appears to help. However, it can be cumbersome and care must be taken to ensure that it does not interfere with early range of motion. The use of continuous passive mobilization (CPM) has not been established. The role of CPM is not solely to passively maintain the range of motion. Indeed, when used properly it has been shown to reduce swelling.41 The motion should be full so the elbow alternately flexes and extends to tighten the tissues, augment lymphatic drainage and prevent oedema. The CPM machine should be set at the range of motion that was achieved at the time of surgery and should not be stopped in the first 24–36 hours. The total end time has been shown to be more important than the number of repetitions, so the slowest speed setting should be used. It can be paused for 30-minute intervals at end range positions only.

Outcome including literature review

Open debridement

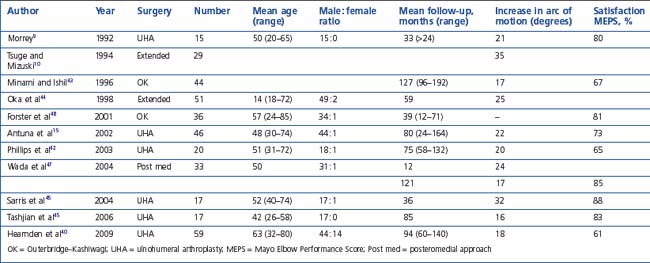

On review of the literature, most authors report modest improvement in pain relief and range of motion, with patients being generally satisfied with the procedure.9,10,15,42–46 Table 40.2 summarizes these data.

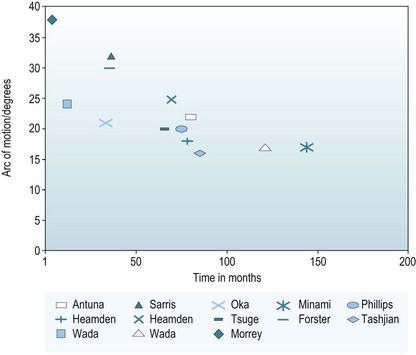

Survivorship

It does appear, however, that the range of motion gained at surgery deteriorates with time; this has been demonstrated in several studies. Minami et al reported a 10% deterioration in range of motion when they compared the same group of patients at 5 years after surgery and then again at 12 years.49 Phillips et al extrapolated the best and worst scenarios for patient-perceived benefit over time.42 They predicted that 50% of patients would still be satisfied at 8 years after surgery. Wada et al measured a 24° increase in the arc of movement 1 year after surgery in their 33 patients.47 However, at the latest follow-up 70% had had a deterioration, a mean of 7° loss between these two time points. The authors concluded that the disease process was progressive, and that patient satisfaction would deteriorate with time.47 When range of motion at follow-up is compared across all the published data, there is a trend that would suggest that studies with the longest follow-up have the poorest range of motion. At our institution 59 patients were followed up for 7.6 years. We looked at the arc of movement at the end of surgery, at 3 months and at a mean follow-up of 7.8 years. Figure 40.9 shows our data along with all the other outcome studies for open debridement. It again demonstrates that the range of motion gained at surgery deteriorates with time.40

Prognostic factors

Forster et al found that patients in whom duration of symptoms was less than 2 years, with considerable pain and one or more loose bodies benefited most from the open debridement.48 Phillips et al42 and Antuna et al15 found no correlation between the functional assessment and reappearance of the bone with the fenestration of the olecranon fossa.

Recurrence of osteophytes

Oka et al44 studied the recurrence of osteophytes radiographically and found mild arthrosis in 75% and moderate recurrence of osteophytes in the remaining 25%. The spurs were less severe, however, than the preoperative arthrosis in all cases and none had required revision surgery at a mean of 5 years. Phillips et al42 found no correlation between deteriorating function and recurrence of bone with the fenestration of the olecranon fossa. However, Wada et al47 reoperated on two patients who had lost motion as a result of pain and osteophyte recurrence.

Return to work

Oka et al44 included two populations: the 26 athletes returned to their sport and all 24 manual labourers returned to their occupation with only one having some limitation. Phillips et al42 reported 75% return to their previous jobs, 6% changed to a lighter work, 2% become unemployed and 6% retired. In the Wada series47 all of the office workers returned to their work, while 76% of heavy manual labourers returned to the same job, 12% retired and 12% transferred to working in an office.

Interposition arthroplasty

Only a few papers have reported the results of interposition arthroplasty; it is not a common operation and the numbers are small. The extent of bone resection, the type of graft used, the role of ligament reconstruction and the use of a dynamic external fixation have not been optimized. The Mayo group has the largest series and are currently pleased with the use of Achilles allograft. However, the results of interposition arthroplasty are inconsistent with 24–30% of patients having a poor result, confirming that it is salvage surgery and should be considered only as a last resort.30,31,36–38,50 Eight to 15% required revision to total elbow replacement as a result of pain or instability; fortunately total elbow replacement after a failed interposition arthroplasty has good results. Instability is the leading cause for failure. Patients who have preoperative instability have a higher failure rate and as a consequence it should be considered a contraindication. Most studies report a reduction in pain after the interposition surgery but rarely achieve an asymptomatic joint; therefore patients with a painless loss of motion should not be offered this surgery.

Complications of open debridement

The literature demonstrates that there is a significant complication rate associated with open elbow debridement; between 12% and 19% of patients experienced an adverse incident or required further surgery. Forster et al48 reported a 17% complication rate (three ulnar nerve and one wound infection) with 8% requiring revision surgery; two patients had revision OK procedures and a third patient underwent an ulnar nerve release. Tashjian et al45 reported 12%; one infection and one patient required subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve. Antuna and Morrey recorded two acute neurological complications, two patients returned to theatre for manipulation under anaesthesia to maintain the range of motion within the first 8 weeks and a further two patients required revision debridement. In addition 29% complained of some degree of ulnar nerve symptoms postoperatively; they also found that untreated ulnar nerve symptoms had contributed to a poorer outcome at follow-up.15 As a consequence they concluded that the nerve should be aggressively evaluated prior to surgery. Phillips et al reported no infection or ulnar nerve damage.42

1 Peterson LF, Janes JM. Surgery of the rheumatoid elbow. Orthop Clin North Am. 1971;2(3):667-677.

2 Buzby B. End results of excision of the elbow. Ann Surg. 1936;103:625-634.

3 Kirkaldy-Willis W. Excision of the elbow joint. Lancet. 1948;1:53-57.

4 Hurri L, Pulkki T, Vainio K. Arthroplasty of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Chir Scand. 1964;127:459-465.

5 Defontaine L. Osteotomie trochleiforme: nouvelle method pour la cure des ankylosis osseus du coude. Rev Chir. 1887;7:716-726.

6 Hass J. Functional arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1944;26:297-306.

7 Minami M. Roentgenological studies of oeteoarthritis of the elbow joint. J Jap Orthop Assoc. 1977;51:1223-1236.

8 Kashiwagi D. Intraarticular changes of the osteoarthritic elbow. J Jap Orthop Assoc. 1978;52:1367-1382.

9 Morrey BF. Primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow. Treatment by ulnohumeral arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1992;74:297-299.

10 Tsuge K, Mizuski T. Debridement arthroplasty for advanced primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1994;76:641-646.

11 Stanley D. Prevalence and etiology of symptomatic elbow osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3:386-389.

12 Josefsson PO, Johnell O, Gentz CF. Long-term sequelae of simple dislocation of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1984;66:927-930.

13 O’Driscoll SW, An KN, Korinek S, et al. Kinematics of a semi constrained total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1992;74:297-299.

14 Dalal S, Bull M, Stanley D. Radiographic changes at the elbow in primary osteoarthritis: a comparison with normal aging of the elbow joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:358-361.

15 Antuna SA, Morrey BF, Adams RA, et al. Ulnohumeral arthroplasty for primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow: longterm outcome and complications. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2002;84:2168-2173.

16 Linscheid RL, Wheeler DK. Elbow dislocations. JAMA. 1965;194(11):1171-1176.

17 Sharma S, Rymaszewski LA. Open arthrolysis for post traumatic stiffness of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2007;89:778-781.

18 Kozak K, Adams R, Morrey BF. Total elbow arthroplasty in primary degenerative osteoarthritis of the elbow. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:837-842.

19 Kelberine F, Landreau P, Cazal J. Arthroscopic management of the stiff elbow. Chir Main. 2006;25:S108-S113.

20 Park JY, Cho CH, Choi JH, et al. Radial nerve palsy after arthroscopic anterior capsular release for degenerative elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:1360.e1-1360.e3.

21 Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2001;83:25-34.

22 Ruch DS, Poehling GG. Anterior interosseus injury following elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:756-758.

23 Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L. Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:784-787.

24 Cohen AP, Redden JF, Stanley D. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow: a comparison of open and arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:701-706.

25 Redden JF, Stanley D. Arthroscopic fenestration of the olecranon fossa in the treatment of osteoarthriris of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:14-16.

26 Freed JH, Hahn H, Mentor R. Use of three phase bone scan in early diagnosis of heterotopic ossification and its evaluation of didronel therapy. Paraplegia. 1982;20:208.

27 Garland DE, Orwin JF. Resection of heterotopic ossification in patients with spinal cord injuries. Clin Orthop. 1989;242:169-176.

28 Stover SL, Hataway CJ, Zeiger HE. Heterotopic ossification in spinal-cord injured patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1976;58:683.

29 McAuliffe JA, Wolfson AH. Early excision of heterotopic ossification about the elbow followed by radiation therapy. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1997;79:749-755.

30 Larson N, Morrey BF. Interposition arthroplasty as a salvage procedure of the elbow using an Achilles tendon allograft. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2008;90:2714-2723.

31 Nolla J, Ring D, Lozano-Calderon S, et al. Interposition arthroplasty of the elbow with hinged external fixation for post-traumatic arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:459-464.

32 Froimson AI, Silva JE, Richey DG. Cutis arthroplasty of the elbow joint. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1976;58:863-865.

33 Kita M. Arthroplasty of the elbow using J-K membrane. An analysis of 31 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1977;48:450-455.

34 Knight RA, Zandt ILV. Arthroplasty of the elbow: an end result study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1952;34:610-618.

35 Cheung SL, Morrey BF. Treatment of the mobile, painful arthritic elbow by distraction interposition arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2000;82:233-238.

36 Morrey BF. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow. Operative treatment, including distraction arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1990;72:601-618.

37 Froimson AI, Morrey BF. Interposition arthroplasty of the elbow. In: Morrey BF, editor. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery: The Elbow, vol. 105. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002:391-408.

38 Shahriaree H, Sajadi K, Silver CM, et al. Excisional arthroplasty of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1979;61:922-927.

39 Smith MA, Savidge GF, Fountain EJ. Interposition arthroplasty in the management of advanced haemophilic arthropathy of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1983;65:436-440.

40 Hearnden A, Talwalker S, Roy N, et al. Ulnohumeral Arthroplasty in the management of the arthritic elbow. Shoulder Elbow. 2009;1:95-98.

41 Flowers KR, LaStayo P. Effect of total end range time on improving passive range of motion. J Hand Ther. 1994;7:150-157.

42 Phillips NJ, Ali A, Stanley D. Treatment of primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow by ulnohumeral arthroplasty. A long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2003;85(3):347-350.

43 Minami M, Ishil S. Outerbridge-Kashiwagi arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the elbow: 44 elbows followed for 8–16 years. J Orthop Sci. 1996;1:6-11.

44 Oka Y, Ohta K, Saitoh I. Debridement arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the elbow. Clin Orthop. 1998;351:127-134.

45 Tashjian RZ, Wolf JM, Ritter M, et al. Functional outcomes and general health status after ulnohumeral arthroplasty for primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:357-366.

46 Sarris I, Riano F, Goebel F, et al. Ulnohumeral arthroplasty: results in primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow. Clin Orthop. 2004;420:190-193.

47 Wada T, Isogai S, Ishii S, et al. Débridement arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2004;86:233-241.

48 Forster MC, Clark CI, Lunn PG. Elbow osteoarthritis: Prognostic indicators in ulnohumeral debridement- the outerbridge Kashiwagi procedure. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:557.

49 Minami M, Kato S, Kashiwagi D. Outerbridge Kashiwagi’s method for arthroplasty of osteoarthritis of the elbow: 44 elbows followed for 8–16 years. J Orthop Sci. 1996;1:11-15.

50 Hausman MR, Birnbaum PS. Interposition elbow arthroplasty. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2004;8:181-188.