CHAPTER 6 One-stop gynaecology

the role of ultrasound in the acute gynaecological patient

Introduction

Acute gynaecological symptoms such as pelvic pain and bleeding occur in pregnant women who have miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies and pregnancies of unknown location, or in women who are not pregnant with ovarian cyst accidents or acute pelvic inflammatory disease. The investigation of the acute gynaecological patient is moving away from the accident and emergency department and operating theatre, and into dedicated emergency gynaecology units (EGUs) located in an outpatient setting (Jones and Pearce 2009). EGUs offer an efficient way of organizing multidisciplinary services for women presenting with acute gynaecological symptoms. These changes have been driven by the demands of the patient and clinician to provide a rapid, accurate diagnosis, with the minimum of investigations and invasive procedures. They are underpinned by national standards and guidelines (Department of Health 2003, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2006). Furthermore, changing from traditional care pathways to more cost-effective, patient-centred approaches to medical practice lies at the heart of modern health service management (Department of Health 2000, Jones 2008).

In the UK, the majority of gynaecological ultrasound scanning has traditionally been undertaken by radiographers and radiologists in a separate department on a separate day. Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) is a pivotal investigation for the assessment of acute gynaecological patients. Therefore, in order to deliver modern acute gynaecological services, gynaecologists will have to learn these new skills (Jones 2005). TVUS probes, providing high-resolution images of the pelvic organs, have an established role in the characterization of adnexal masses, providing reliable and reproducible information regarding cyst type and probability of malignancy (Granberg et al 1989, 1990, Tailor et al 1997, Timmerman et al 1999a), particularly when they are used in combination with tumour markers (Moore et al 2008). They have superiority over transabdominal probes because of the higher resolution of pelvic anatomy. There is also no need for a full bladder, improving patient acceptability.

TVUS is a pivotal investigation in the delivery of an ‘Ambulatory Gynaecology Service’ (Jones 2008). This is a more comprehensive term which would include the assessment of patients with non-acute gynaecological symptoms such as menstrual disorders, postmenopausal bleeding and chronic pelvic pain. The discussion of these conditions falls outside the scope of this chapter.

Resources for Services

Ultrasound machine

Most gynaecology units will already have an ultrasound machine that can be used within a clinic setting. Minimum requirements are a transvaginal probe (6–7.5 MHz), a 3.5 MHz abdominal transducer and facilities for capturing images, either as a hard copy or digitally. A portable machine can be a wise investment if it is to be shared, for example, with the delivery suite, or to allow for ultrasound-guided procedures in the operating theatre. The ultrasound machine should not be more than 5 years old (Royal College of Radiologists/Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 1995).

Reducing the risk of infection transmission

TVUS is a relatively non-invasive procedure. There is, however, a moderate risk of transmission of infection as the probe comes into contact with mucous membranes. The risk of infection is reduced by the use of an appropriate cover for the transducer. It is estimated that up to 7% of covers will sustain perforations, and contamination of the probe may also occur on removing the cover after use (Jimenez and Duff 1997). As a result, appropriate cleaning of the transducer must occur between patients. Sterilization of the probe is not practical, and disinfection using a germicidal (e.g. 70% alcohol) cloth or spray, after first wiping off the gel, is effective. The probe is then left to air dry for at least 5 min. Basic hygiene measures, such as washing hands after each case and ensuring that contaminated gloves do not come into contact with the ultrasound machine, must be used to minimize cross-infection. There is no need for the routine use of antibiotics during ultrasound scanning.

Analgesia

TVUS is a well-tolerated procedure, even in women who present with acute pelvic pain. It does not require the routine use of analgesia. Basama et al (2004) demonstrated that TVUS was considered acceptable, and not painful, embarrassing or stressful in a study of 425 women undergoing TVUS in an emergency setting.

Ultrasound-guided ovarian cyst aspiration

It is important that the ovarian cysts are unilocular and thin walled if the technique is going to be successful and safe. Subtle, superficial, internal mural nodules or small papillary excrescences should be searched for meticulously because these features may indicate a malignant lesion, in particular a borderline tumour. With careful attention to ultrasound surveillance, cyst aspiration can be performed safely (Caspi et al 1996, Troiano and Taylor 1998). In 33–50% of cases, cyst aspiration will constitute definitive therapy. In other cases, cysts will recur and it is important to remember that cytology alone is not sufficiently accurate to exclude malignancy. Cyst recurrence after drainage is higher than if the capsule is removed (Balat et al 1996), but cyst fluid cytology is not always representative of the cyst wall pathology (Dietrich et al 1999).

Cyst aspiration in pregnant women is also feasible, and this technique is useful for functional cysts that become large and symptomatic (Khaw and Walker 1990). Cyst aspiration decreases the risk of rupture or torsion. Cysts that persist into later pregnancy are more likely to be serous or mucinous, and may be malignant. However, in some cases, it may be useful to aspirate the cyst and to remove it post partum. Such treatment may be warranted after careful assessment because surgical treatment for cysts in pregnancy is not without risk, with reported miscarriage rates between 2% and 35%.

The Emergency Gynaecological Unit

The provision of an EGU is now recognized as a gold standard service (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2006). It provides an easily accessible outpatient area with facilities for ultrasound-based assessment of pregnancy duration, viability and location, This allows the clinician to provide informed management and counselling of the patient in a setting which maximizes her privacy and comfort. The EGU should have a dedicated area for the triage, assessment and initial management of patients presenting with acute gynaecological disorders, including early pregnancy complications. There should be a separate area where the patient can change, a designated waiting area with toilet facility, and bed/trolley spaces to accommodate women who need to recline. An initial assessment of the clinical condition can be made and recorded on a preformed history sheet. The cost benefits of the EPU are well established (Bigrigg and Read 1991) as admission can be avoided in approximately 40% of patients, with a further 20% requiring a shorter stay. Ideally, there should be a dedicated unit for the assessment and investigation of women with suspected complications of early pregnancy. This will be centred around an ultrasound scanning room, run by dedicated ultrasound practitioners. There should be a private area in which the patient can change and also a separate counselling room with access to a counselling service and outside line telephone.

Anti-D immunoglobulin use

Current guidelines (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2000 & 2006) for the use of rhesus immunoprophylaxis in early pregnancy recommend that anti-D immunoglobulin should be given to all non-sensitized rhesus-D-negative women who have:

Ultrasound Overview

TVUS should be regarded as an extension of a bimanual examination rather than a replacement. A recent prospective comparative trial of endovaginal sonographic bimanual examination versus traditional digital bimanual examination in non-pregnant women with lower abdominal pain has been reported (Tayal et al 2008). The study clearly demonstrated that vaginal examinations combined with TVUS improved confidence in key findings, such as ovarian and uterine size or position irrespective of the patient’s body mass index. The advantages of TVUS over the transabdominal approach are well documented (Gonzalez et al 1988, Mendelson et al 1988). The placement of the ultrasound probe closer to the pelvic organs means that higher frequency ultrasound transducers (6–7.5 MHz) can be used, which produce high-resolution images. TVUS assessment of ovarian volume and morphology correlates closely with subsequent operative findings at laparotomy (Rodriguez et al 1988).

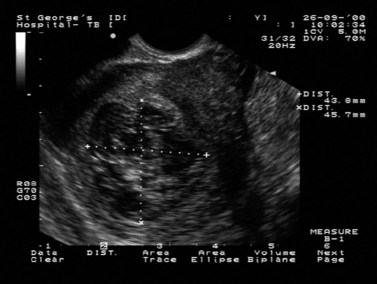

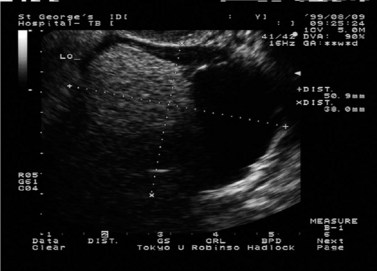

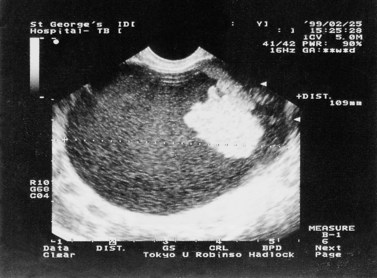

No single ultrasound measurement of the different anatomical features in the first trimester has been shown to have a high predictive value for determining early pregnancy outcome, and Doppler studies are not helpful either (Jauniaux et al 2005). Despite this, high-resolution TVUS has transformed understanding of the pathophysiology and management of early pregnancy failure. The ultrasound findings in both a normal pregnancy and a failing pregnancy are well described (Dogra et al 2005). The intrauterine gestation sac can be visualized from approximately 4 weeks after the last menstrual period using a transvaginal transducer, which is approximately 2 weeks earlier than if using the transabdominal approach (Fossam et al 1988). This is dependent upon a regular 28-day cycle, and hence a more accurate approach to confirming pregnancy viability or failure is dependent upon either changes with time or the presence or absence of fetal cardiac activity. The diameter of the gestational sac increases at approximately 1 mm/day in early pregnancy (Nyberg et al 1985), and can be differentiated from the ‘pseudosac’ of ectopic pregnancy by its thick, echogenic rind surrounding the echo-lucent central chorionic sac and eccentric location to the endometrial midline. The presence of a normal intrauterine gestation sac is associated with β-hCG levels of >1000 IU. Detection at levels greater than this is dependent upon a number of factors, including type of probe and ultrasound machine used, the presence of leiomyomas, operator variations and multiple gestations (Nyberg et al 1985, Bernaschek et al 1988). The absence of a gestation sac should prompt the operator to look for an extrauterine gestation (including a close examination of the cornua and cervix as well as the adnexa). Visualization of the yolk sac is regarded as definitive evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy. The yolk sac can be visualized from 5 weeks’ gestation (Figure 6.1), and the early embryonic pole from approximately 6 weeks. First recognized as a thickening along the yolk sac, it is linear to begin with, subsequently becoming curved in nature. The embryonic growth rate is 1 mm/day. Cardiac activity starts at approximately 5 weeks after the last menstrual period. Cardiac activity not detected in embryos of more than 4 mm is associated with embryonic demise (Brown et al 1990, Levi et al 1990, Goldstein 1992). However, a repeat scan to confirm diagnosis is always indicated. Embryonic bradycardia can be associated with poor outcome (Doubilet et al 1999), and a follow-up scan is warranted to confirm viability.

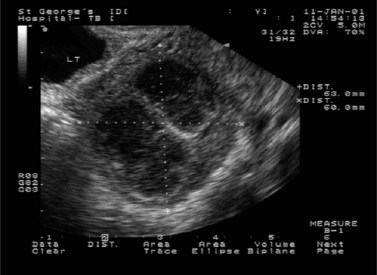

TVUS has an established role in the evaluation of adnexal masses. It provides an accurate assessment of ovarian morphology (Granberg et al 1989, 1990, Timmerman et al 1999b) and is a significant contributor to mathematical models being developed to assess ovarian tumours (Tailor et al 1997, Timmerman et al 1999a,c). There are several types of ovarian cyst that can be assessed using the recognition of characteristic morphological patterns (Jermy et al 2001). Endometriomas and benign cystic teratomas are two examples, accounting for over two-thirds of persistent adnexal masses in premenopausal women (Koonings et al 1989). These lesions can be particularly difficult to score using morphological scoring systems, and as angiogenesis is ubiquitous throughout the ovarian cycle, colour Doppler is of limited value (Alcazar et al 1997).

Clinical Conditions

Bleeding and/or pain with a positive pregnancy test

Sensitive urinary pregnancy testing kits, based on immunological assays, are able to detect β-hCG levels of between 20 and 50 IU with 99% accuracy. This has meant that an increasingly large number of women will present with bleeding and/or pain in early pregnancy. It has been estimated that approximately 30% of women will complain of pain or bleeding during early pregnancy, and approximately 15% of clinically recognizable pregnancies will result in miscarriage, the majority before the 13th week (Prendiville 1997). Due to the large volume of work in such a highly sensitive area of gynaecology, an integrated approach to diagnosis and management of women presenting with bleeding and/or pelvic pain during the first trimester is required.

Miscarriage

Once the diagnosis of intrauterine pregnancy has been established, the potential viability of the pregnancy will need to be addressed. The clinical value of the normal developmental timespan of the early embryonic and extraembryonic structures is its application in the diagnosis of pregnancy failure. What becomes more relevant is not the earliest point at which a structure can be seen (threshold), but the point at which a structure is always seen in a normally developing intrauterine pregnancy (discriminatory level), so its absence is diagnostic of pregnancy failure. Once an ectopic pregnancy has been excluded, all intrauterine pregnancies should be given the benefit of the doubt and serial scans should be performed to confirm a diagnosis. However, cardiac activity should always be visualized in an embryo measuring 6 mm or more (Figure 6.2).

Terminology

Trouble shooting

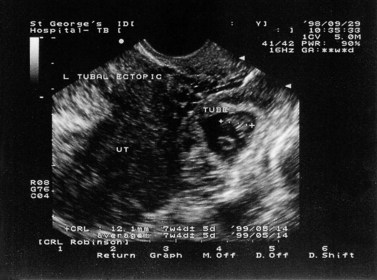

Ectopic pregnancy

Figure 6.5 Cornual ectopic pregnancy. The gestation sac is seen separately from the endometrial echo.

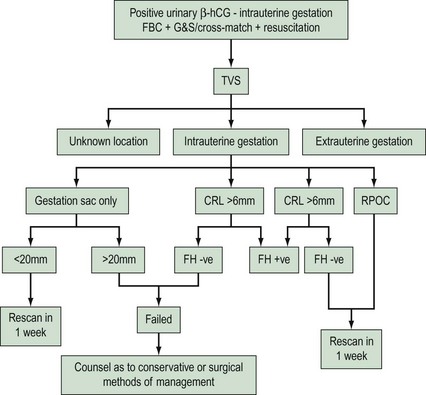

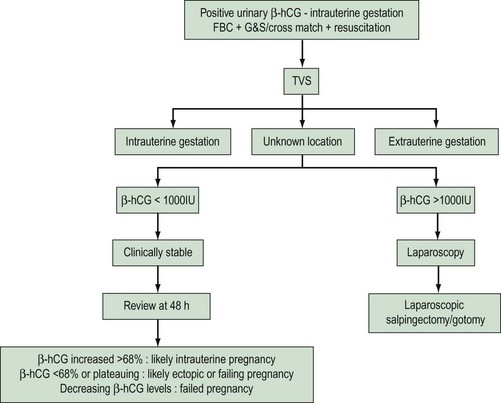

Further management of the patient will be dependent upon her clinical status. Within the authors’ unit, there has been a significant reduction in patients presenting with acute haemodynamic compromise due to a ruptured ectopic pregnancy since the EPU was established. This has meant that more conservative methods of treatment can be used, whether surgical (laparoscopic salpingectomy, salpingotomy), medical (methotrexate) or expectant (Figure 6.7).

All non-surgical methods of treating ectopic gestations will need intensive follow-up to ensure resolution of symptoms and β-hCG values. Patient compliance is central to these patients being treated on an outpatient basis, along with a dedicated EPU service (see Chapter 25, Ectopic pregnancy, for more information).

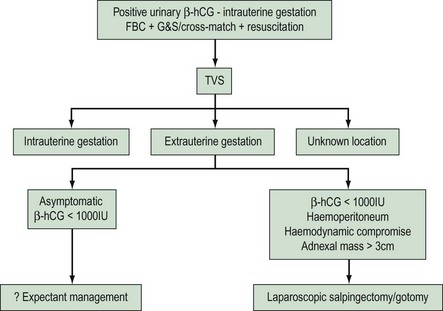

Pregnancy of unknown location

A proportion of women presenting with complications of early pregnancy will have no sonographic features of extra- or intrauterine pregnancy. This group will include patients who have a very early, continuing, intrauterine pregnancy, those who have an ectopic gestation and those who have a failing pregnancy, whether intra- or extrauterine. Rarely, a false-positive result may be due to a placental site tumour, for example of the ovary. Figure 6.8 demonstrates a suggested follow-up regime for women who fall into this category. Again, a coordinated EPU and rapid β-hCG assay service are essential.

Postnatal assessment

Few studies have targeted the normal ultrasound parameters of the uterus and ovaries in the postnatal period. The sonographic appearances of retained products of conception are variable (Carlan et al 1997, Hertzberg and Bowie 1991). One study evaluating the appearance of the uterine cavity revealed an echogenic mass in 51% of women with normal postpartum bleeding at 7 days post partum (Edwards and Ellwood 2000). Sonohysterography has been shown to enhance the ability of TVUS to diagnose retained products of conception (Wolman et al 2000), although in the presence of suspected pelvic infection, this procedure should not be performed. Management should be based primarily on clinical findings, with sonographic evaluation of the uterus and endometrium reserved for those cases with persistent symptoms. Rarely, arteriovenous malformations can cause protracted, heavy bleeding in the puerperium. If suspected, colour Doppler assessment of the uterine vasculature will aid their diagnosis, prior to arteriography and embolization. If surgical evacuation of retained products of conception is performed in the immediate postnatal period, the recognized higher morbidity associated with the procedure can be reduced by evacuating the uterus under sonographic guidance (Kohlenberg and Casper 1996).

The premenopausal patient

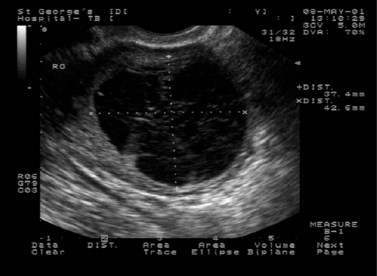

Pelvic pain in association with a pelvic mass

A careful history and a clear knowledge of the day of the menstrual cycle will prompt the sonographer to the most likely cause of the pain. For example, acute-onset, midcycle pain may be indicative of a follicular or corpus luteal cyst accident. Haemorrhage into a corpus luteal cyst has characteristic sonographic findings (Figure 6.9). The condition tends to be self-limiting and often responds to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesia. Surgery should be avoided if possible.

Figure 6.9 Haemorrhagic corpus luteal cyst. Fine strands of fibrin are seen within the cyst contents.

Women with a history suggestive of endometriosis presenting with acute pain may have sonographic evidence of an endometrioma (Figure 6.10). These rarely undergo torsion, as they are often fixed within the pelvis, but may undergo rupture or acute haemorrrhage within the cyst. Rarely, they can become infected. Recent cyst rupture may be suggested by the presence of resolving clinical symptoms, with free fluid present in the pouch of Douglas, often with a collapsing irregular cyst wall.

Figure 6.10 Large ovarian endometrioma: characteristic ‘ground-glass’ appearance of the cyst contents.

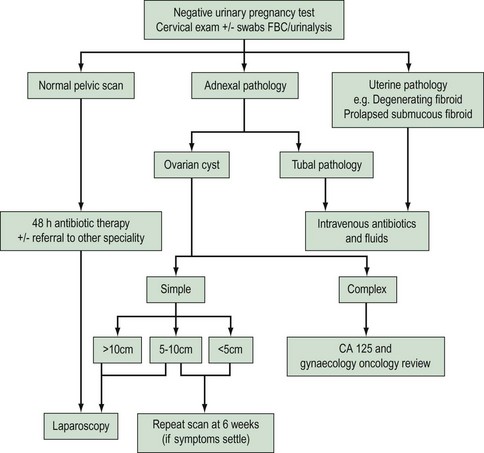

A suggested follow-up regime for women diagnosed with a pelvic mass is shown in Figure 6.11. Intervention will be dictated by the resolution, or not, of the patient’s symptoms. If the symptoms resolve and there are no sonographic features of malignancy on the ultrasound, a repeat scan at 6 weeks should be performed to confirm cyst resolution.

Ovarian torsion is unusual with adnexal masses <5 cm (Nicholas and Julian 1985). However, there are no pathognomonic features specific to adnexal torsion, and a high degree of clinical suspicion is essential. The clinical history is of acute-onset, constant pain that does not respond to analgesia, often with nausea and vomiting and systemic upset. Of the persistent adnexal masses in premenopausal women, benign cystic teratomas (Figure 6.12) are more likely to undergo torsion than endometriomas. The central feature of ovarian torsion is the cessation of vascular supply. Colour Doppler has therefore been used to interrogate the adnexal mass suspected of undergoing torsion. It is likely, however, that even if flow can be visualized within the mass, despite clinical symptoms and signs of ovarian torsion, ovarian blood flow may still be compromised, as demonstrated by surgically proven ovarian torsion despite the detection of blood flow within the mass (Rasado et al 1992).

Tubal pathology

Acute inflammatory processes within the fallopian tubes tend to produce thick-walled, cystic structures, tender to the touch of the probe (Figure 6.13). However, a chronic hydrosalpinx will have the appearance of a thin-walled structure, not obviously tender on probing and often detected coincidentally (Timor-Tritsch et al 1998).

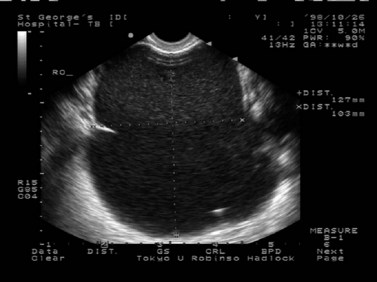

The postmenopausal patient

Characterization of any adnexal mass is important within this age group as the risk of a mass being malignant is high (Figure 6.14). Unilocular cysts may be found in up to 20% of asymptomatic postmenopausal women. Numerous studies have shown that simple, unilocular cysts measuring <5 cm in diameter are associated with a very low risk of malignancy (Kroon and Andolf 1995). Blood should be taken for tumour markers and emergency laparotomy should be avoided if at all possible, to allow for adequate oncological work-up of the patient if indicated. Urinary retention must be excluded. Other chronic surgical and medical conditions are more predominant in the older age group, such as diverticulitis, constipation and urinary tract infections. Early recourse to advice from other specialties should be considered in women with pelvic or abdominal pain.

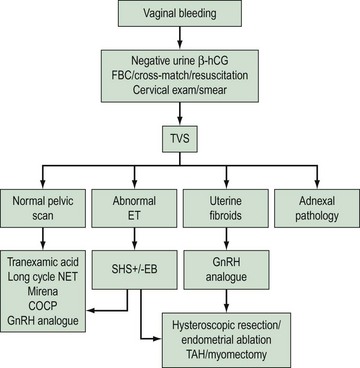

Acute bleeding and a negative pregnancy test

The investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding will centre on an assessment of the endometrium (Figure 6.15). Undirected endometrial sampling alone has no role in the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. It will miss focal lesions, such as polyps and fibroids. Whilst TVUS remains a cost-effective, non-invasive, well-tolerated technique for examining the pelvic organs, it is less specific than hysteroscopy when differentiating between endometrial polyps, myomas, carcinoma and hyperplasia. The addition of a negative contrast medium, such as saline, into the uterine cavity addresses this problem. An overwhelming quantity of data has shown that high-resolution TVUS with saline instillation is as predictive as hysteroscopy in the detection of endometrial pathology.

The premenopausal patient

The main differentials within this group are genital tract disease, systemic disease and iatrogenic causes. When all these have been excluded, a diagnosis of dysfunctional uterine bleeding can be made. History, clinical examination and pelvic ultrasound will help to elucidate the cause. Disease of the genital tract in this age group will focus on benign rather than malignant conditions. Benign pelvic conditions will include fibroids, endometrial and cervical polyps, cervicitis, adenomyosis and endometriosis, along with pelvic infection and foreign bodies. Systemic problems contributing to abnormal uterine bleeding will include coagulation disorders, chronic liver and renal disease, and thyroid dysfunction. Iatrogenic causes will include anticoagulant therapy, intrauterine contraceptive devices and hormonal preparations. There needs to be heightened suspicion of an underlying systemic disease in younger patients presenting with heavy vaginal bleeding, as up to 20% (Kadir et al 1998) may have a coagulopathy. Screening for a coagulopathy is also advised in women with abnormal vaginal bleeding who fail medical or surgical therapy. The endometrial thickness on ultrasound will dictate the need for endometrial sampling, as will the patient’s history.

Conclusion

The National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services (Department of Health 2003) is clear in its aim of providing patient-centred care with the identification and appropriate management of relevant social, medical and psychiatric problems, with a one-stop assessment, diagnosis and management ethos as set out in the NHS Plan (Department of Health 2000). EGUs are excellent examples of how this aspiration can be translated into clinical practice. TVUS plays a pivotal role in assessment of the acute gynaecological patient; as such, it is the core investigating modality in the EGU. It complements a full clinical examination, affording a ‘view’ of the pelvic structures. Its integration into the gynaecology emergency service facilitates more rapid diagnosis in a number of gynaecological conditions. It also helps to exclude gynaecological pathology, ensuring prompt referral to other specialties and multidisciplinary teams. Central to its appropriate use will be training and supervision, with up-to-date protocols and regular audit, and awareness of the limitations of personnel and the equipment.

KEY POINTS

Balat O, Sarac K, Sonmez S. Ultrasound guided aspiration of benign ovarian cysts: an alterntive to surgery. European Journal of Radiology. 1996;22:136-137.

Basama FM, Crosfill F, Price A. Women’s perception of transvaginal sonography in the first trimester in an early pregnancy assessment unit. Archives of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2004;269:117-120.

Bernaschek G, Rudelstorfer R, Csascsich P. Vaginal sonography versus serum human chorionic gonadotrophin in early detection of pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1988;158:608-612.

Bigrigg MA, Read MD. Management of women referred to early pregnancy assessment unit: care and cost effectiveness. British Medical Journal. 1991;302:577-579.

Brown DL, Emerson DS, Felker RE. Diagnosis of embryonic demise by endovaginal sonography. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 1990;9:711-716.

Caspi B, Goldchmit R, Zalel Y, Appelman Z, Insler V. Sonographically guided aspiration of ovarian cyst with simple appearance. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 1996;15:297-300.

Carlan SI, Scott WT, Pollack R, Harris K. Appearance of the uterus by ultrasound immediately after placental delivery with pathologic correlation. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound. 1997;25:301-308.

Department of Health. The NHS Plan. A Plan for Investment, a Plan for Reform. London: HMSO; 2000.

Department of Health. The National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services. London: HMSO; 2003.

Dietrich M, Osmers RG, Grobe G, et al. Limitations of the evaluation of adnexal masses by its macroscopic aspects, cytology and biopsy. European Journal of Gynaecology and Reproduction Biology. 1999;82:57-62.

Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Cow JS. Long-term prognosis of pregnancies complicated by slow embryonic heart rates in the early first trimester. Journal of Ultrasound Medicine. 1999;18:537-541.

Dogra V, Paspulati RM, Bhatt S. First trimester bleeding evaluation. Ultrasound Quarterly. 2005;21:149-154.

Edwards A, Ellwood DA. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the postpartum uterus. Ultrasound in. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;16:640-643.

Fernandez H, Yves Vincent SC, Pauthier S, Audibert F, Frydman R. Randomised trial of conservative laparoscopic treatment and methotrexate administration in ectopic pregnancy and subsequent fertility. Human Reproduction. 1998;13:3239-3243.

Fossam GT, Davajan V, Kletzky OA. Early detection of pregnancy with transvaginal ultrasound. Fertility and Sterility. 1988;49:788-791.

Goldstein SR. Significance of cardiac activity on endovaginal ultrasound in very early embryos. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;80:670-672.

Gonzalez CJ, Curson R, Parson J. Transabdominal versus transvaginal ultrasound scanning of ovarian follicles: are they comparable. Fertility and Sterility. 1988;50:657-659.

Granberg S, Wikland M, Jansson I. Macroscopic characterisation of ovarian tumors and the relation to the histological diagnosis: criteria to be used for ultrasound evaluation. Gynecologic Oncology. 1989;35:139-144.

Granberg S, Norström A, Wikland M. Tumors in the lower pelvis as imaged by transvaginal sonography. Gynecologic Oncology. 1990;37:224-229.

Hafner T, Aslam N, Ross JA, Zosmer N, Jurkovic D. The effectiveness of non-surgical management of early interstitial pregnancy: a report of ten cases and review of the literature. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;13:131-136.

Hertzberg BS, Bowie JD. Ultrasound of the postpartum uterus. Prediction of retained placental tissue. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 1991;10:451-456.

Jauniaux E, Johns J, Burton GJ. The role of ultrasound imaging in diagnosing and investigating early pregnancy failure. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;25:613-624.

Jermy K, Luise C, Bourne T. The characterization of common ovarian cysts in premenopausal women. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;17:140-144.

Jimenez R, Duff P. Sheathing of the endovaginal probe: is it adequate? Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;1:37-39.

Jones KD. Gynaecological training in a consultant delivered service: a European perspective. The Obstetrician and Gynaecologist. 2005;7:126-128.

Jones KD, editor. Ambulatory Gynaecology: a New Concept in Healthcare for Women. RCOG Press, London, 2008;1-11. Chapter 1

Jones K, Pearce C. Organizing an acute gynaecology service: equipment and set up. Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2009;23:425-426.

Khaw KT, Walker WJ. Ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration of ovarian cysts: diagnosis and treatment in pregnant and non-pregnant women. Clinical Radiology. 1990;141:105-108.

Kadir RA, Economides DL, Sabin CA, Owens D, Lee CA. Frequency of inherited bleeding disorders in women with menorrhagia. The Lancet. 1998;351:485-489.

Kohlenberg CF, Casper GR. The use of intraoperative ultrasound in the management of a perforated uterus with retained products of conception. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;36:482-484.

Koonings PP, Campbell K, Mishell D, Grimes D. Relative frequency of ovarian neoplasms: a 10 year review. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1989;74:921-925.

Kroon E, Andolf E. Diagnosis and follow-up of simple ovarian cysts detected by ultrasound in postmenopausal women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;85:211-214.

Levi CS, Lyons EA, Zheng HX. Endovaginal US: demonstration of cardiac activity in embryos of less than 5 mm in crown rump length. Radiology. 1990;176:71-74.

Ludwig M, Kaisi M, Bauer O, Diedrich K. Heterotopic pregnancy in a spontaneous cycle: do not forget about it!. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1999;87:91-93.

Mendelson EB, Bohm-Velez M, Joseph N, Neiman HL. Endometrial abnormalities: evaluation with transvaginal sonography. American Journal of Radiology. 1988;150:139-142.

Moore RG, Brown AK, Miller CM, et al. The use of multiple novel serum tumor markers for the detection of ovarian carcinoma in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecologic Oncology. 2008;108:402-408.

Nicholas D, Julian P. Torsion of the adnexa. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1985;28:375-380.

Nyberg DA, Filly RA, Mahony BS. Early gestation: correlation of hCG levels and sonographic identification. AJR American Journal of Roentgenology. 1985;144:951-954.

Prendiville WJ. Miscarriage: epidemiological aspects. In: Grudzinskas JG, O’Brien PMS, editors. Problems in Early Pregnancy: Advances in Diagnosis and Management. London: RCOG Press, 1997.

Rasado W, Trambert M, Gosink B, Pretorius D. Adnexal torsion: diagnosis by using Doppler sonography. American Journal of Radiology. 1992;159:1251-1253.

Rodriguez MH, Platt LD, Medearis AL, Lacarra M, Lobo RA. The use of transvaginal ultrasonography for evaluation of postmenopausal ovarian size and morphology. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1988;159:810-814.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2000 Clinical Guideline Number 22. Anti-D Immunoglobulin for Rh Prophylaxis RCOG, London.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Clinical Green Top Guidelines. The Management of Early Pregnancy Loss. London: RCOG Press; 2006.

Royal College of Radiologists/Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Guidance on Ultrasound Procedures in Early Pregnancy. London: RCR/RCOG; 1995.

Tayal VS, Crean CA, Norton HJ, et al. Prospective comparative trial of endovaginal sonographic bimanual examination versus traditional digital bimanual examination in non pregnant women with lower abdominal pain with regard to body mass index classification. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2008;27:1171-1177.

Tailor A, Jurkovic D, Bourne T, Collins W, Campbell S. Sonographic prediction of malignancy in adnexal masses using multivariate logistic regression analysis. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;10:41-47.

Timmerman D, Bourne TH, Tailor A, et al. A comparison of methods for the pre-operative discrimination between benign and malignant adnexal masses: the development of a new logistic regression model. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;181:57-65.

Timmerman T, Schwärzler P, Collins W, et al. Subjective assessment of adnexal masses using ultrasonography: an analysis of interobserver variability and experience. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;13:11-16.

Timmerman D, Verrelst H, Bourne T, et al. Artificial neural network models for the pre-operative discrimination between malignant and benign adnexal masses. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;13:17-25.

Timor-Tritsch IE, Lerner JP, Monteagudo A, Murphy KE, Heller DS. Transvaginal sonographic markers of tubal inflammatory disease. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;12:56-66.

Troiano RN, Taylor KJ. Sonographically guided therapeutic aspiration of benign-appearing ovarian cysts and endometriomas. AJR American Journal of Roentgenology. 1998;171:1601-1605.

Wolman I, Gordon D, Yaron Y, Kupferminc M, Lessing JB, Jaffa AJ. Transvaginal sonohysterography for the evaluation and treatment of retained products of conception. Gynecology and Obstetrics Investigation. 2000;50:73-76.