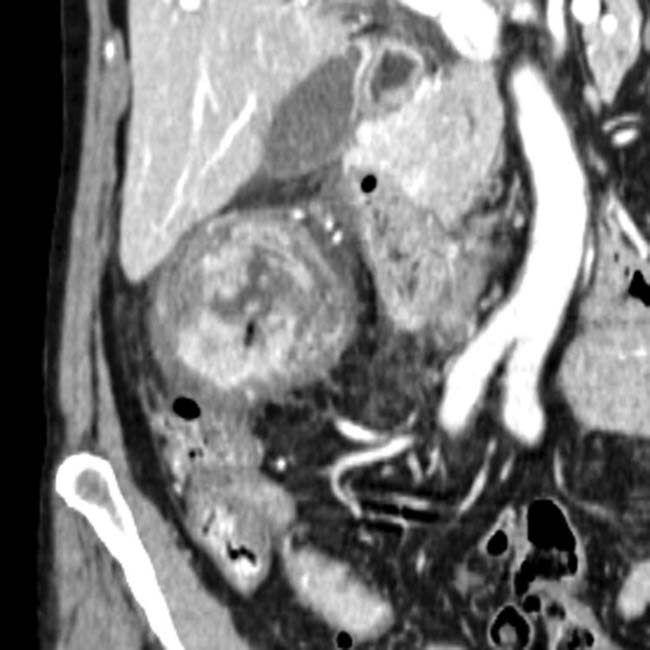

Heterogeneous, encapsulated mass located within omentum (usually in right lower quadrant)

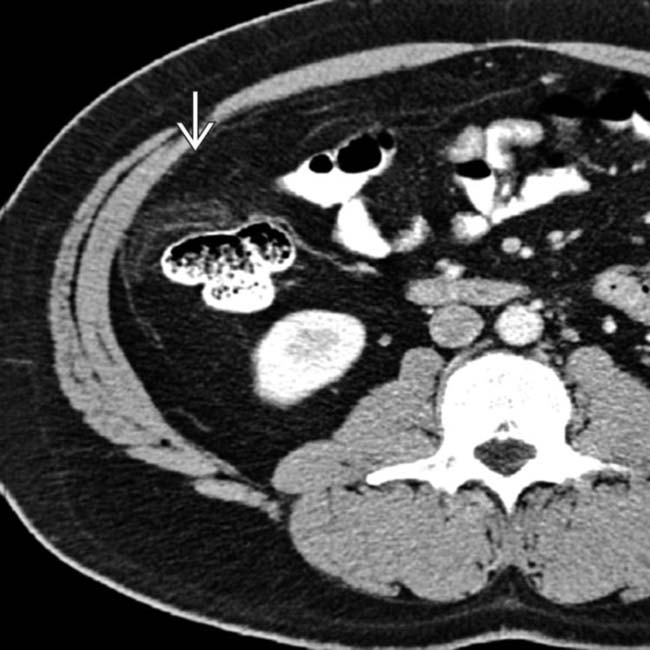

in the omentum with a subtle peripheral rim, in keeping with an omental infarct. The patient’s pain resolved in a few days with conservative therapy.

in the omentum with a subtle peripheral rim, in keeping with an omental infarct. The patient’s pain resolved in a few days with conservative therapy.

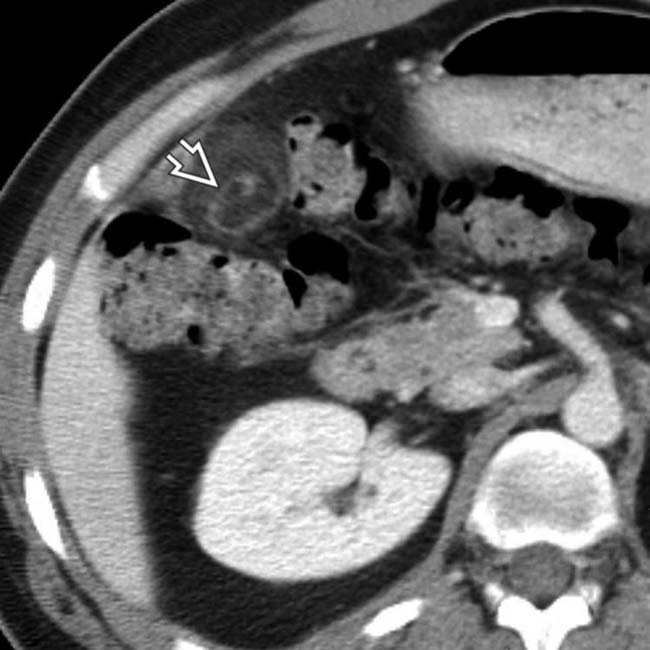

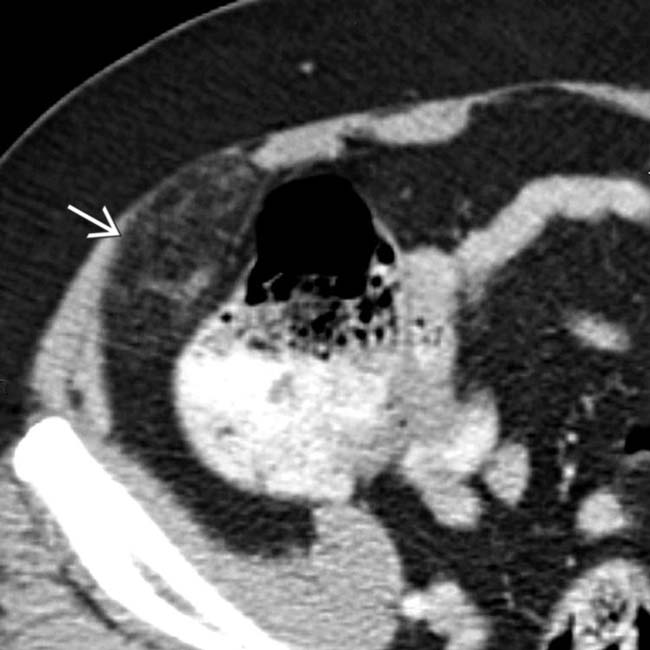

with a peripheral hyperdense rim in the right omentum. The patient had experienced RLQ pain about 1 week earlier, and this was thought to be a subacute omental infarct.

with a peripheral hyperdense rim in the right omentum. The patient had experienced RLQ pain about 1 week earlier, and this was thought to be a subacute omental infarct.

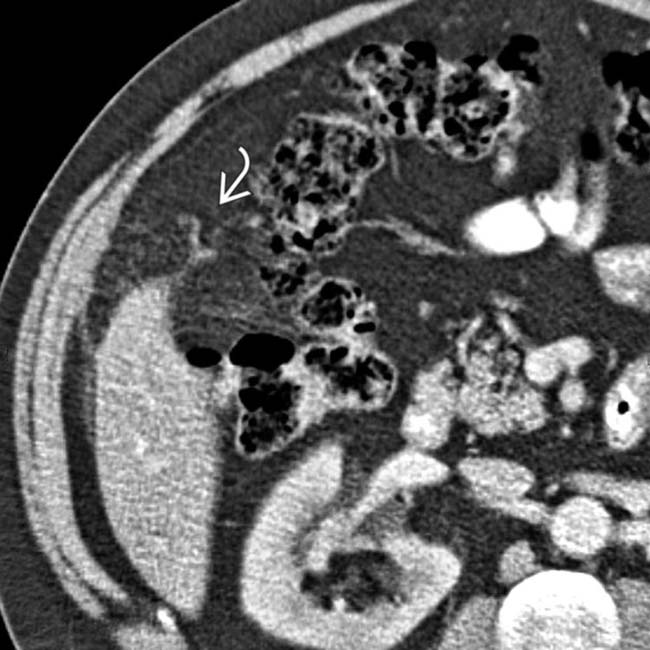

with a hyperdense rim adjacent to the ascending colon.

with a hyperdense rim adjacent to the ascending colon.

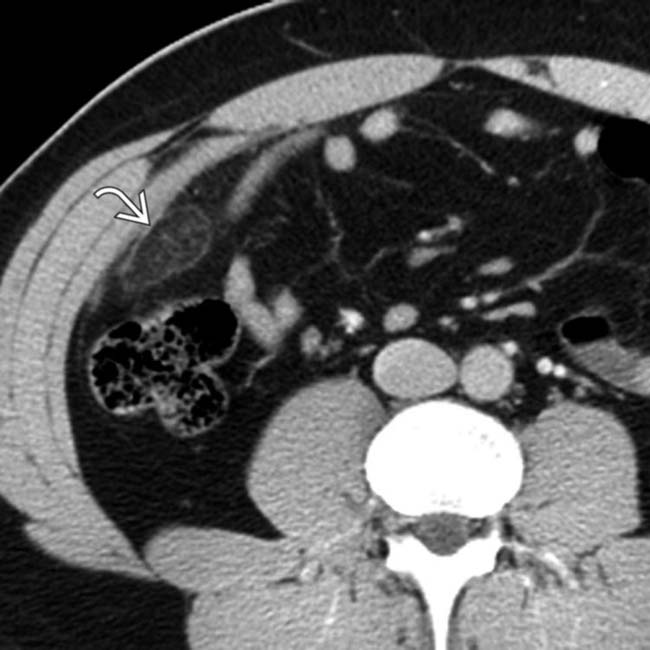

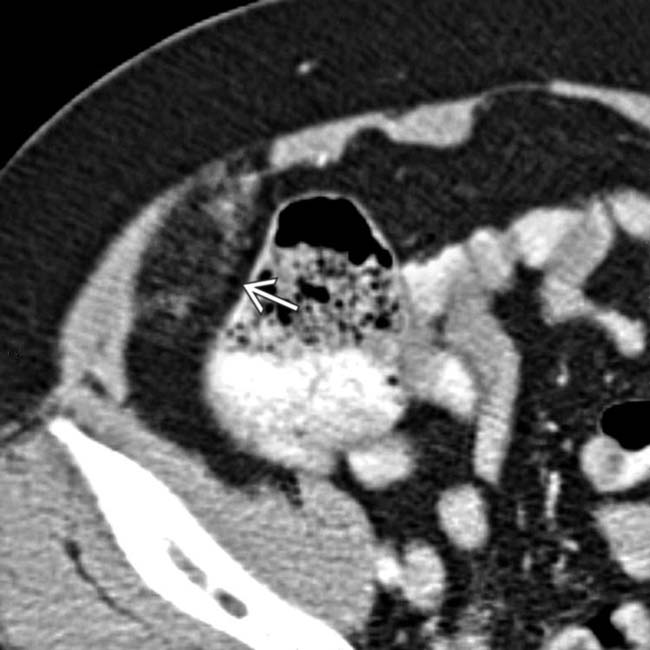

within the infarcted omentum, indicating twisting of the omental pedicle, which may be the etiology of the infarct in some cases.

within the infarcted omentum, indicating twisting of the omental pedicle, which may be the etiology of the infarct in some cases.IMAGING

General Features

CT Findings

• Heterogeneous, encapsulated mass located within omentum between anterior abdominal wall and colon

Can have variable internal attenuation, but usually some internal foci of fat attenuation (-20 to -50 HU)

Can have variable internal attenuation, but usually some internal foci of fat attenuation (-20 to -50 HU)

Can have variable internal attenuation, but usually some internal foci of fat attenuation (-20 to -50 HU)

Can have variable internal attenuation, but usually some internal foci of fat attenuation (-20 to -50 HU)DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Acute Appendicitis

• Can mimic omental infarction clinically, but distinction readily made with cross-sectional imaging

Epiploic Appendagitis

PATHOLOGY

General Features

• Etiology

Multiple other secondary causes reported

Multiple other secondary causes reported

Multiple other secondary causes reported

Multiple other secondary causes reported

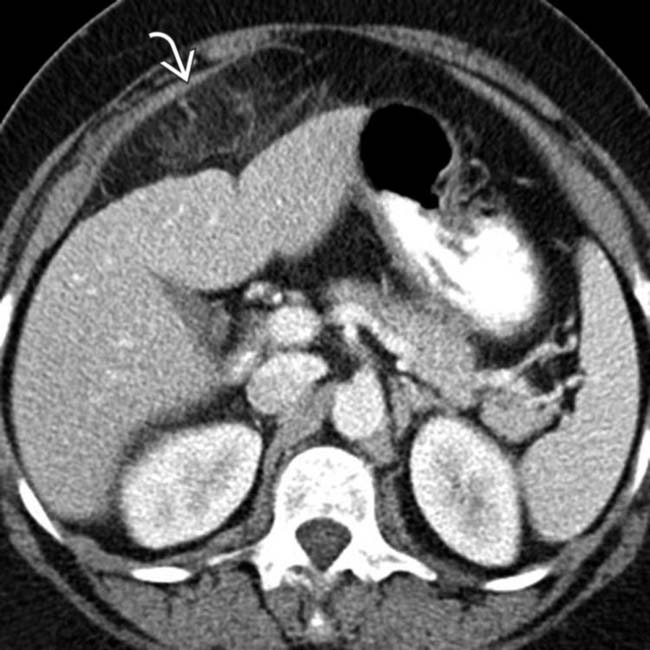

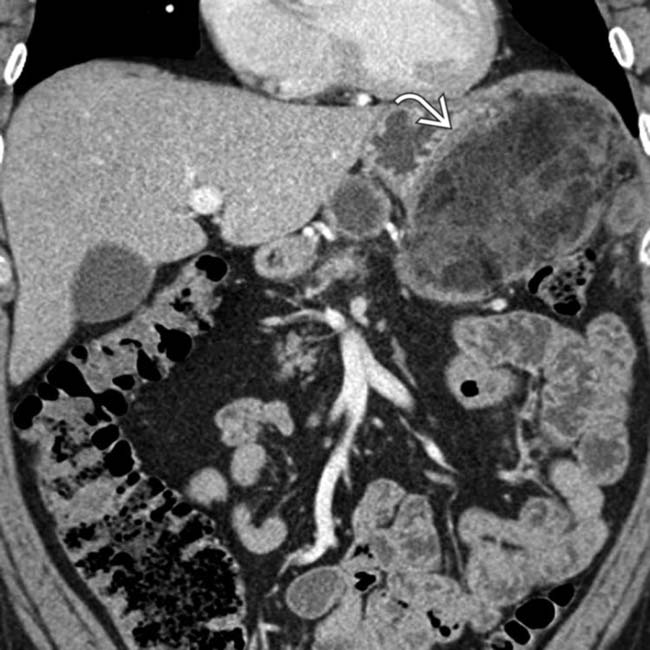

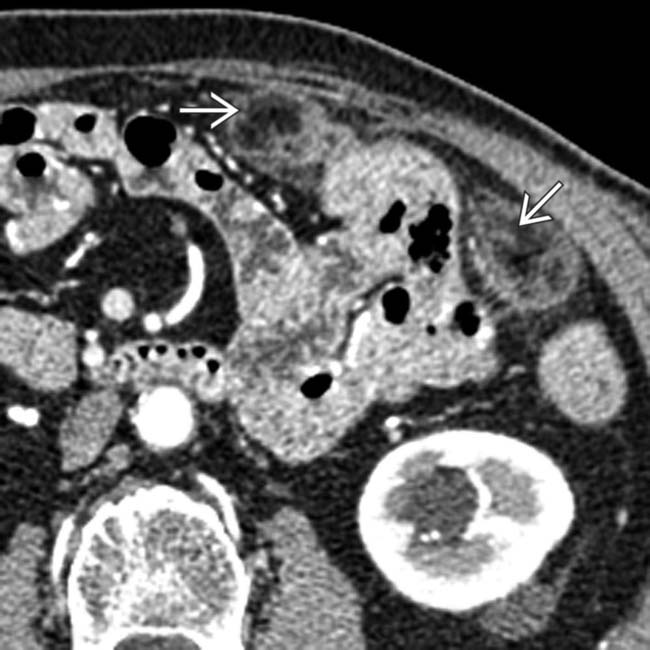

with a hyperdense rim and adjacent inflammation in the right lower quadrant (RLQ) omentum, a classic appearance and location for an omental infarct.

with a hyperdense rim and adjacent inflammation in the right lower quadrant (RLQ) omentum, a classic appearance and location for an omental infarct.

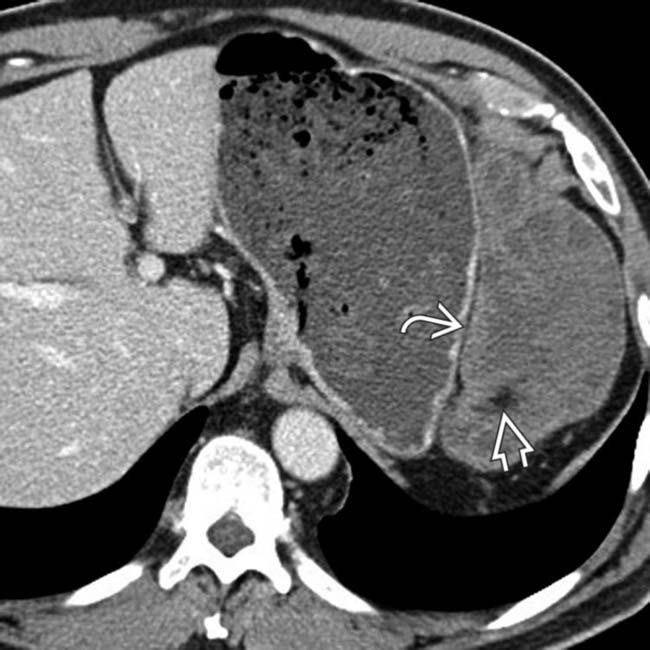

in the left upper quadrant omentum, representing a large omental infarct. Omental infarcts after surgery can be quite large and in proximity to the surgical bed.

in the left upper quadrant omentum, representing a large omental infarct. Omental infarcts after surgery can be quite large and in proximity to the surgical bed.

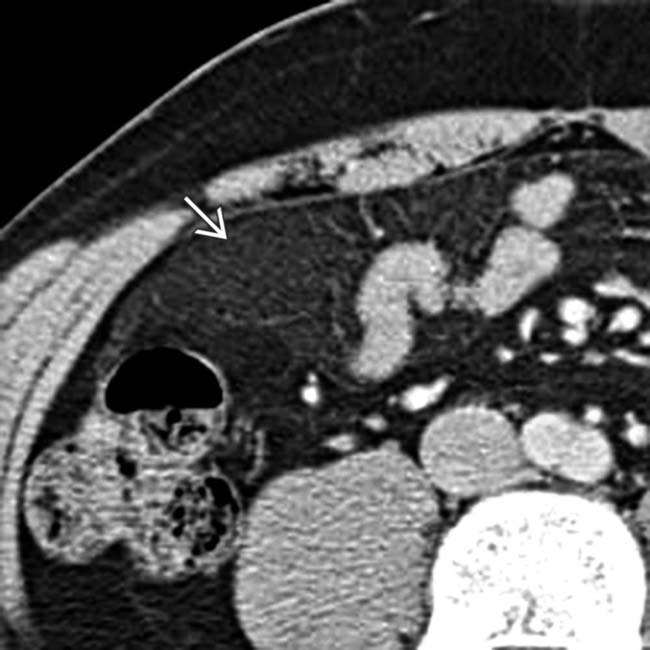

in the RLQ omentum with surrounding fat stranding, characteristic of an omental infarct.

in the RLQ omentum with surrounding fat stranding, characteristic of an omental infarct.

in the LUQ omentum. Note the presence of internal fat density

in the LUQ omentum. Note the presence of internal fat density  within the mass. Omental infarcts, as in this case, can be quite large and mimic a tumor (such as a liposarcoma) or carcinomatosis.

within the mass. Omental infarcts, as in this case, can be quite large and mimic a tumor (such as a liposarcoma) or carcinomatosis.

in the anterior omentum, corresponding to the site of the patient’s pain. This represents an omental infarct likely related to the vasculitis.

in the anterior omentum, corresponding to the site of the patient’s pain. This represents an omental infarct likely related to the vasculitis.

in the RLQ with adjacent fat stranding. The referring physician favored a diagnosis of appendicitis and opted for surgery, where an omental infarct was confirmed.

in the RLQ with adjacent fat stranding. The referring physician favored a diagnosis of appendicitis and opted for surgery, where an omental infarct was confirmed.

.

.

.

.

within the omentum overlying the hepatic flexure. This is the typical site and appearance for spontaneous omental infarction.

within the omentum overlying the hepatic flexure. This is the typical site and appearance for spontaneous omental infarction.

.

.

, overlying the ascending colon.

, overlying the ascending colon.

.

.

.

.

from prior sigmoid resection 2 months previously.

from prior sigmoid resection 2 months previously.

adjacent to the ascending colon. (Courtesy D. Green, MD.)

adjacent to the ascending colon. (Courtesy D. Green, MD.)

in a patient with an omental infarct. (Courtesy D. Avrin, MD.)

in a patient with an omental infarct. (Courtesy D. Avrin, MD.)

, displacing the anterior abdominal wall, representing a large omental infarct.

, displacing the anterior abdominal wall, representing a large omental infarct.

in the RUQ. The gallbladder

in the RUQ. The gallbladder  is normal.

is normal.

to the ascending colon, which is a characteristic feature. The gallbladder

to the ascending colon, which is a characteristic feature. The gallbladder  is again clearly visualized as normal.

is again clearly visualized as normal.

.

.

as a ball of “dirty fat” lying adjacent to the ascending colon. Appropriately, this patient was managed without surgery.

as a ball of “dirty fat” lying adjacent to the ascending colon. Appropriately, this patient was managed without surgery.

as a ball of “dirty fat” adjacent to the ascending colon.

as a ball of “dirty fat” adjacent to the ascending colon.