Chapter 36 Olecranon Bursitis

Introduction

A bursa either communicates with a joint space/tendon sheath or forms in response to friction in order to facilitate movement. There are approximately 140 bursae throughout the body,1 with 50 named and in constant positions.2 Most are deep and are found between tendon and other tendons, ligaments or bone. A small number are subcutaneous, being located between bone and skin. Their walls consist of cellular or collagenous connective tissue and are lined with synovium.3 There are 11 in the vicinity of the elbow of which the olecranon bursa, situated between skin and the posterior aspect of the olecranon process is most frequently affected by inflammation. The normal olecranon bursa contains very little fluid but significant amounts are produced when it is inflamed and this can result in substantial swelling.

An anatomical study of 20 full-term foetuses found that eight had olecranon bursae.4 In contrast, a similar study, based on the dissection of 63 cadavers of varying ages, noted that (i) no olecranon bursae occurred in those under the age of 7, which is consistent with the low incidence of olecranon bursitis in children, (ii) their volume increased with age and (iii) the bursa on the right was larger than that on the left in all those over the age of 10.

A study comparing elbow effusions with olecranon bursitis5 found that the lowest pressure in an elbow joint effusion occurred at 30–40° of flexion and then rose rapidly with further flexion. Baseline pressure within olecranon bursal fluid, however, persisted until approximately 60° of elbow joint flexion and then rose exponentially with further flexion, although this did not cause pain. It was felt more likely that pain arose in receptors in the area between the bursa and the underlying osteo-tendinous structures. It was also noted that, as flexion progressed, the olecranon process including the triceps insertion, moved distally under the bursa. Another difference between joint and bursal fluid is that bursal fluid has poor mucin clot and a lower white cell count, glucose and complement.

Background/aetiology

There are a variety of synonyms for olecranon bursitis:

Clinical Pearl 36.1

Most cases of olecranon bursitis are caused by low level trauma or repetitive elbow movements. Other predisposing factors include conditions causing systemic inflammation or impaired immunity (Table 36.1). There is also an increased incidence in patients on maintenance haemodialysis.

| Traumatic | Repetitive low level trauma, e.g. in miners, mechanics, carpet-layers, book-keepers, wrestlers, gymnasts, gardeners, those with spinal cord injury, those with tardive dyskinesia (by causing involuntary movements while leaning on elbows) |

| Single direct impact | |

| Penetrating injury, e.g. laceration, surgical incision, intrabursal steroid injection, internal fracture fixation | |

| Distal triceps tendon injury | |

| Systemic inflammation | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Gout | |

| Calcium pyrophosphate deposition (pseudogout) | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Pigmented villonodular synovitis | |

| Impaired immunity | Diabetes |

| Steroid therapy | |

| Malignancy | |

| Human immune deficiency syndrome | |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | |

| Uraemia | |

| Monoclonal gammopathy | |

| Myelodysplasia | |

| Alcoholism | |

| Intravenous drug abuse | |

| Miscellaneous | Adjacent internal fixation metalwork maintenance haemodialysis |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |

| Psoriasis | |

| Scleroderma | |

| Sunitinib therapy (used in treatment of renal cell carcinoma) |

A study of mononuclear cells in the fluid from aseptic olecranon bursitis has revealed ‘a preponderance of activated T cell subpopulations and monocyte/macrophages’ suggesting that there is ‘an immunologic role in the development and perpetuation’ of this condition.6 The authors proposed that trauma to the bursa caused synovial damage, increasing permeability and exposing the vascular endothelium.

Aseptic olecranon bursitis

In most, but not all, cases of aseptic bursitis the history suggests a predisposing cause. The most common is low level trauma such as occurs when repeatedly leaning on the elbow (Table 36.1). Other cases are associated with more substantial trauma including direct impact, a laceration and surgery. It has also been reported in association with a distal triceps tendon injury but whether this is cause or effect is unclear. Integrity of the distal triceps tendon should, however, always be tested. Systemic inflammatory conditions, impaired immunity and miscellaneous other conditions are also associated with this condition.

Rheumatoid synovitis can affect the olecranon bursa and may predate a more generalized manifestation of the disease.3 Rheumatoid nodules and gouty tophi in this area may form within the bursa or be extra-bursal. Calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition (pseudogout) can also occur and give rise to bursitis.

Inflammation of the serous membranes (pericardium, pleura and peritoneum), i.e. serositis, is known to occur in uraemic patients and this may explain the increased incidence of olecranon bursitis in those receiving haemodialysis. The condition nearly always occurs in the same limb as the vascular access and the possibility of it being caused by repeated low level trauma to this area has also been raised. In most reported cases the elbow has rested on the arm of a chair and it is suggested that prolonged pressure over the olecranon with small movements during the few hours of dialysis is the cause of the bursitis. However, one group reported three cases despite the practice of performing the procedure with the patient in bed and with padding behind the elbows.1

Septic olecranon bursitis

Approximately one-third of cases of olecranon bursitis are septic and yet clinically distinguishing them from non-septic cases is difficult. The portal of entry for the infecting organism is usually the skin. The haematogenous route is rare. A past history of septic bursitis and the presence of rheumatoid nodules or gouty tophi are associated with an increased risk of infection.7

Although Staphylococcus aureus is the commonest cause of infection numerous other organisms have been reported (Table 36.2) many of them as single case reports. Some infections are caused by mixed flora. There is a significant association with conditions or therapy that impair immunity (Table 36.1). In all rheumatoid patients with septic olecranon bursitis the possibility of septic arthritis of the elbow should be considered.8

Table 36.2 Organisms reported to cause septic olecranon bursitis

| Gram-positive | Staphylococcus aureus |

| Group A streptococci (Streptococcus pyogenes) | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | |

| Enterococcus | |

| Gram-negative | Enterobacter |

| Serratia marcescens | |

| Escherichia coli | |

| Haemophilus influenzae | |

| Brucella abortus | |

| Neisseria | |

| Atypical | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| Atypical mycobacteria | |

| Nocardia | |

| Achlorophyllic algae (Prototheca species) | |

| Fungi | Candida |

| Phaeoacremonium species | |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | |

| Anthopsis deltoidea |

Presentation

The typical patient is a middle-aged male but the condition can occur in both sexes and over a wide age distribution. It is uncommon in children. One-third of patients have significant comorbidities.10 The time of presentation varies widely. Some patients report a history of trauma or prior bursal disease. The history must include a full enquiry for predisposing factors (Table 36.1) including inflammatory joint disease, uraemia with haemodialysis and conditions that impair immunity. Unusual organisms cultured from bursal fluid in cases of septic bursitis are often associated with the latter.

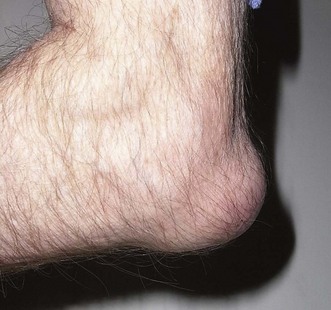

The normal bursa is not usually palpable, although it may become somewhat nodular in older people. When inflammation (bursitis) occurs, an effusion develops within the bursa (Fig. 36.1) that then becomes swollen, often conspicuously. It may or may not be painful. In a study largely based on patients with olecranon bursitis it was concluded that (i) tension within the bursal wall was not a major contributor to pain, (ii) puncturing the bursal base usually led to pain and (iii) pain was usually experienced during extension against resistance.5

At times the swelling is striking and may be associated with a cellulitis. In the absence of an elbow joint synovitis or effusion, flexion beyond 60–90° may be associated with pain over the olecranon but passive extension is not usually affected.11 This is in contrast to septic arthritis where all movement is usually painful. It is generally true that aseptic olecranon bursitis is associated with less marked symptoms than septic bursitis so the restriction of motion, tenderness, erythema, cellulitis and elevation in temperature all tend to be less. While these features are more likely to be present in septic bursitis their absence does not rule it out. In the presence of septic bursitis a sterile effusion of the elbow joint may occur while aseptic bursitis may be present at the same time as synovitis in the joint due to rheumatoid arthritis or gout.12 A discharging sinus may develop, particularly in those with rheumatoid arthritis. In this situation there is a high risk that the sinus will communicate with the elbow joint causing a septic arthritis. If this occurs treatment should be commenced urgently. Extensive forearm swelling because of leaking from an olecranon bursitis secondary to rheumatoid arthritis has been reported.

The features of aseptic and septic olecranon bursitis have been compared, revealing substantial overlap.12 This makes clinical diagnosis difficult and so the final judgement should be based on bursal fluid culture.

Clinical Pearl 36.5

All cases have a swollen usually fluid-filled bursa overlying the olecranon. Recent skin damage, redness, tenderness (none, mild, moderate or severe), heat, fever, cellulitis around the bursa and in the forearm and/or an overlying skin lesion or ulcer may be present. A rheumatoid nodule (Fig. 36.2) or gouty tophus may be present. Establishing whether infection is present is important.

Investigation

Bursal fluid should be aspirated, placed in a sterile container and sent for Gram stain, culture and sensitivities, white cell count, cell type, glucose level and crystal analysis. The serum glucose should also be measured so that the ratio of bursal to serum glucose can be calculated. The Gram stain is negative in approximately 30% of cases that subsequently prove on culture to be infected and so it does not reliably indicate a lack of infection.7 If the initial culture is negative, the other indices can help to distinguish between aseptic and septic fluid but the specificity is low. White cell counts of up to 1000/mm3 with a predominance of mononuclear cells are more likely to be found in aseptic fluid, while counts of greater than 10 000/mm3 with a predominance of polymorphonuclear cells suggest infection. There is, however, substantial overlap between these values. A fluid glucose level of less than 50% of the serum level also points towards infection.

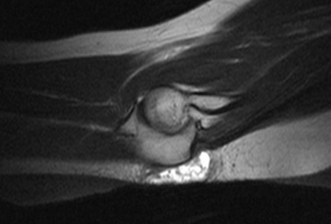

The surface temperature of the bursa is higher in the presence of infection and this has been used to aid in distinguishing between aseptic and septic bursitis. The use of a surface temperature probe for this purpose has been shown to have 100% sensitivity and 94% specificity in discriminating between the two conditions.13 If there is doubt about the diagnosis, ultrasound scanning can be used to aid the identification of early cases and to distinguish olecranon bursitis from other causes of swelling around the elbow. It can demonstrate synovial proliferation, calcification, loose bodies, rheumatoid nodules (Fig. 36.2) and gouty tophi. Hyperechoic particles within the bursal fluid suggest a haemorrhagic, inflammatory or septic aetiology.

All cases should have anteroposterior and lateral X-rays of the affected elbow. In simple aseptic olecranon bursitis the only abnormality is soft tissue swelling (Fig. 36.3). A gouty tophus may be seen (Fig. 36.4). The main indication for obtaining X-rays is to look for evidence of osteomyelitis, bony erosion or adjacent joint involvement. In one study,14 olecranon spurs and amorphous deposits or both were present in 57% of patients and 14% of controls. It remains unclear as to whether they predispose to the condition. In the presence of a sinus, a sinogram helps to establish if there is communication with the elbow joint.

MRI scanning (Fig. 36.5) is not often undertaken as there is considerable overlap in the appearance of aseptic and septic olecranon bursitis. Sepsis is, however, unlikely in the absence of bursal and soft tissue enhancement. If there is concern about underlying osteomyelitis, MRI may be considered but the appearances are not specific.15

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

Conservative management

In the presence of aseptic traumatic olecranon bursitis patients whose symptoms do not resolve spontaneously may settle with aspiration and the application of a firm compression bandage. If benefit is not achieved using this approach consideration should be given to aspiration of the bursa and steroid injection. While this has been shown to rapidly accelerate recovery, one study with a mean follow-up of 31 months reported that it was also associated with complications such as infection (12%), skin atrophy (20%) and chronic pain when leaning on the elbow (28%). These complications did not occur in those patients who had aspiration alone.16 Another study with a follow-up of 1, 3 and 6 weeks together with a 6-month questionnaire confirmed the efficacy of intrabursal steroid and reported no adverse local effects such as bursal infection and atrophy of the skin or subcutaneous tissue.17 Canoso and Sheckman, however, suggested that the risk of introducing infection when injecting the bursa with corticosteroid may be significantly higher than with intra-articular injection.11 In those who are slow to respond, the possibility of immune compromise should be considered.

Surgical management

In one study involving 21 procedures in 20 patients with a minimum follow-up of 2 years and an average of 5.2 years, complete relief of symptoms occurred in 94% of those without rheumatoid arthritis but only in 40% of those with rheumatoid arthritis.18 The authors reported that no deep infection and no draining wounds occurred. In another study involving 37 bursectomies, wound healing problems occurred in 10 (27%) with recurrence of the bursitis in 8 (22%).19 These authors advised 3–4 weeks of postoperative cast immobilization and suggested that wound tension could be avoided if the cast was applied with the elbow in less than 60° of flexion.

Primary treatment most commonly involves aspiration or incision and drainage of the bursa combined with antibiotic therapy. The optimum route for antibiotic administration is, however, unclear with one series that used both oral and intravenous treatment reporting a 100% cure rate12 while another noted significant failure rates for oral therapy.20 Intravenous therapy while providing rapid therapeutic levels has the disadvantage that hospital admission is usually required due to the limited availability of community services for intravenous antibiotic administration. Successful treatment has, however, been reported using a home parenteral therapy programme.10

The sooner the antibiotic therapy is started after the onset of infection the more rapidly that sterilization of the bursal fluid occurs. In one study, sterilization occurred within a mean of 4.4 days when symptoms had been present for less than 7 days and 9.2 days when they had been present for 7 days or longer.12 In another study, sterilization occurred within 1 week if antibiotic therapy was commenced within 2 weeks of the onset of symptoms but was delayed if the symptoms had been present for longer.21

The duration of therapy varies between published series. In one report, parenteral therapy was given for a mean of 7.3 (1–17) days and then followed by oral therapy for a mean of 11.1 (6–28) days.20 All cases resolved, with a return to baseline status by a mean of 40 (10–135) days. Other work suggests that antibiotic therapy is required for 5 days after bursal fluid culture becomes sterile. Treatment should be continued for longer in those who have had symptoms for longer and in those with impaired immunity from any cause.

Where the infection is severe with intense cellulitis, significant pyrexia and systemic toxicity, inpatient treatment with intravenous antibiotics is mandatory. Sometimes circulatory support may also be necessary. In the immune-compromised patient bacteraemia can occur and infection extend to involve the adjacent bone or elbow joint.7

The treatment plan is different if a sinus is present. In the rheumatoid patient the infected bursa may be in communication with the elbow joint (Figs 36.6–36.8) resulting in septic arthritis.8 While sinuses can heal spontaneously, early excision with bursectomy and synovectomy are often required. In this scenario immune-modifying medication should be minimized in the perioperative period.

Various other techniques have been reported for dealing with refractory cases. They include the injection of a sclerosant such as tetracycline in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or talcum powder in patients having revision surgery for recurrent olecranon bursitis, radiosynoviorthesis (radiation synovectomy), endoscopic resection and excision of the olecranon process with preservation of the bursa.22 Plastic surgical reconstructive procedures to cover skin defects due to the bursitis or occurring following bursectomy have been reported. They include radical excision of the infected tissue with fasciocutaneous flap coverage,23 debridement and adipofascial flap coverage,24 and a de-epithelialized double-breasted flap with bursal excision and elbow joint synovectomy.25

1 Handa PS, Khaliq SU. Swelling of olecranon bursa in uremic patients receiving hemodialysis. Can Med Assoc J. 1978;118:812-814.

2 Rosse C, Gaddum-Rosse P. Hollinhead’s Textbook of Anatomy. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997.

3 Athanasou N. Colour Atlas of Bone, Joint and Soft Tissue Pathology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998.

4 Whittaker CR. The arrangement of the bursae in the superior extremities of the full-time foetus. J Anat Physiol. 1910;44(2):133-136.

5 Canoso JJ. Intrabursal pressures in the olecranon and prepatellar bursae. J Rheumatol. 1980;7(4):570-572.

6 Smith DL, Bakke AC, Campbell SM, et al. Immunologic characteristics of mononuclear populations found in nonseptic olecranon bursitis. J Rheumatol. 1994;21(2):209-214.

7 McAfee JH, Smith DL. Olecranon and prepatellar bursitis. Diagnosis and treatment. West J Med. 1988;149:607-610.

8 Viggiano DA, Garrett JC, Clayton ML. Septic arthritis presenting as olecranon bursitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1980;62:1011-1012.

9 Cea-Pereiro JC, Garcia-Meijide J, Mera-Varela A, et al. A comparison between septic bursitis caused by staphylococcus aureus and those cause by other organisms. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;20:10-14.

10 Laupland KB, Davies HD. Olecranon septic nursitis managed in an ambulatory setting. Clin Invest Med. 2001;24(4):171-178.

11 Canoso JJ, Sheckman PR. Septic subcutaneous bursitis. Report of sixteen cases. J Rheumatol. 1979;6(1):96-102.

12 Ho G, Tice AD. Comparison of nonseptic and septic bursitis. Arch Intern Med. 1979;139:1269-1273.

13 Smith DL, McAfee JH, Lucas LM, et al. Septic and nonseptic olecranon bursitis. Utility of the surface temperature probe in the early differentiation of septic and nonseptic cases. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1581-1585.

14 Saini M, Canoso JJ. Traumatic olecranon bursitis. Radiologic observations. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1982;23(3A):255-258.

15 Floemer F, Morrison WB, Gongartz G, et al. MRI characteristics of olecranon bursitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:29-34.

16 Weinstein PS, Canoso JJ, Wohlgethan JR. Long-term follow-up of corticosteroid injection for traumatic olecranon bursitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984;43:44-46.

17 Smith DL, McAfee JH, Lucas LM, et al. Treatment of nonseptic olecranon bursitis. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:2527-2530.

18 Stewart NJ, Manzanares JB, Morrey BF. Surgical treatment of aseptic olecranon bursitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(1):49-54.

19 Degreef I, De Smet L. Complications following resection of the olecranon bursa. Acta Orthop Belg. 2006;72:400-403.

20 Raddatz DA, Hoffman GS, Franck WA. Septic bursitis: presentation, treatment and prognosis. J Rheumatol. 1987;14(6):1160-1163.

21 Ho G, Su EY. Antibiotic therapy of septic bursitis. Its implication in the treatment of septic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24(7):905-911.

22 Quayle JB, Robinson MP. A useful procedure in the treatment of chronic olecranon bursitis. Injury. 1978;9(4):299-302.

23 Ip TC, Jones NF. Treatment of chronic infected olecranon bursitis radical excision and radial forearm flap coverage. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2001;5(2):112-116.

24 Lai CS, Tsai CC, Liao KB, Lin SD. The reverse lateral arm adipofascial flap for elbow coverage. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39(2):196-200.

25 MacQuillan A, Josty IC, Murison MSC. Deepithelialized double-breasted flap with synovectomy of the elbow: new technique for the management of refractory olecranon bursitis. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;48(4):451-452.