Older people

Introduction

In demographic terms, the UK has an ageing population. From 1971 to 2021 the number of people in the UK aged 65 and over is expected to increase by nearly 70 % from 7.3 million to 12.2 million (Office for National Statistics 2006), because average life expectancy in the UK has doubled in the last 200 years. By 2021, there will be more people over 80 than under the age of 5; over a quarter of the population will be over 60. The number of people aged over 65 years is escalating, with the fastest-growing group being those aged over 80 years. In England and Wales, the numbers in this age group increased by >1.2 million between 1981 and 2007 (from 1.5 to 2.7 million), from 2.8% to 4.5% of the population. It is suggested that by 2021 there are expected to be 601 000 people aged 90 and over (Office for National Statistics 2009).

More older people are likely to be admitted to hospital as the population ages; often this is via the ED as the gateway to hospital care. Older peoples’ health problems are also often complex clinically and managerially, thus time consuming and challenging for clinical staff (Bridges et al. 2005, Beynon et al. 2011).

Background

There is evidence from the UK, North America and Europe that people who live in areas of socio-economic deprivation have higher rates of emergency admissions, after adjusting for other risk factors. In the UK, admission rates are significantly correlated with measures of social deprivation (Majeed et al. 2000). Socio-demographic variables explain around 45 % of the variation in emergency admissions between GP practices, with deprivation more strongly linked to emergency than to elective admission (Duffy et al. 2002). Practices serving the most deprived populations have emergency admission rates that are around 60–90 % higher than those serving the least deprived populations (Purdy 2010, Purdy et al. 2011).

There have been concerns about the quality of care delivered to older people for many years. The Health Advisory Service 2000 (1998) identified eight major issues affecting the care of older people (Box 22.1). It was reported that older people waited longer in the ED than any other patient group (Association of Community Health Councils for England and Wales 2001); however, it was also acknowledged that older people present with more complex needs and take longer to process (Clark & Fitzgerald 1999). Meyer & Bridges (1998) found evidence of negative attitudes amongst nurses towards older people in the ED. Spilsbury et al. (1999) interviewed ED patients about their experiences. They reported concerns about lack of assessment, long waiting times, and staff not taking into account their sensory or physical problems while not giving consideration to their privacy, safety and comfort. They also stated that staff did not appear to understand their pre-admission circumstances. Meyer & Bridges (1998) concur, stating that ED nurses perceive their role as primarily providing biomedical care rather than nursing care. This prompted the Royal College of Nursing A&E Nursing Association to release a mission statement on the care of older people in the ED, which highlights the need to:

‘Provide an environment appropriate to meeting the needs of older people, by creating a culture and supporting practice that is respectful of the complex needs, rights, desires, dignity and life experience’ (Sowney 1999).

Higgins et al. (2007) describe the persistent negative attitudes of nurses towards older people in acute clinical settings and the National Service Framework for Older People creates a benchmark to underpin the care of older people (Department of Health 2001a). The aim of this document is to address their needs, by promoting knowledge-based practice and partnership working between those who use and those who provide a service (Department of Health 2001a). This highlights the need for emergency nurses to have expert understanding of the ageing process, specialist assessment whilst also developing practice through leadership, teaching and mentoring. Nikki et al. (2012) argue that more attention should also be paid to empathic encounters with family members, who will know the patient’s previous functional capacity and medication, which is decisive information when planning further care and thinking about the patient coping at home.

Physiology of ageing

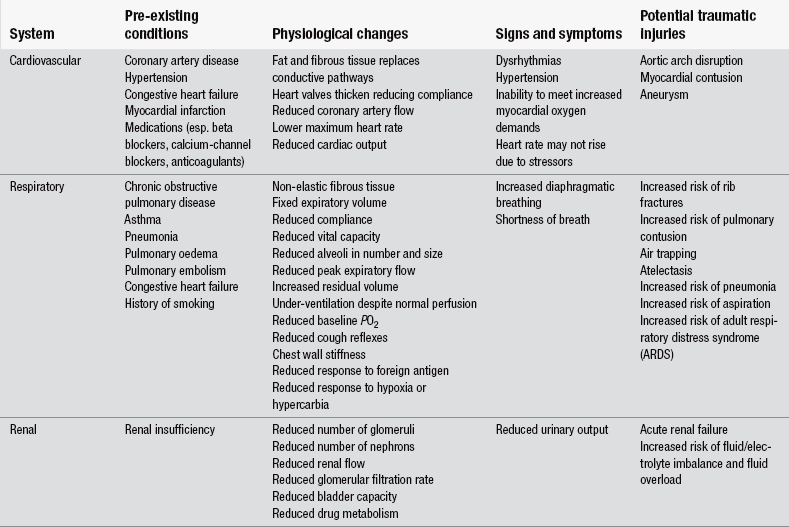

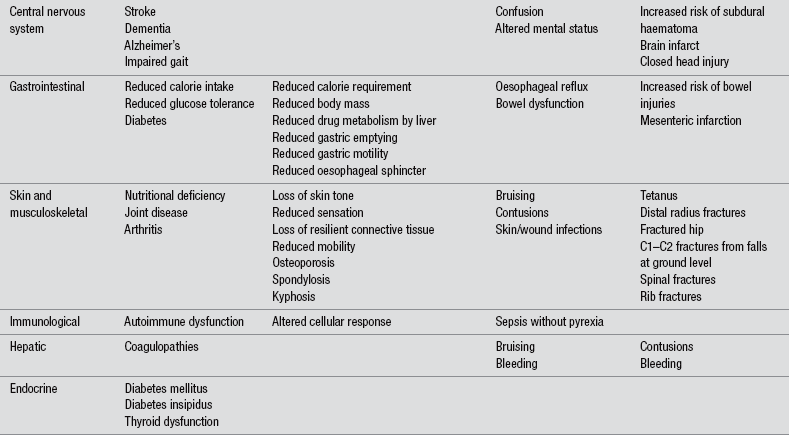

There is no single unifying theory of ageing and it has recently been investigated as a complex, multifactorial process. Death and ageing are distinct entities, but ageing is associated with numerous gradual declines in physiological function that will inevitably lead to death. In broad terms there are two categories of theories to ageing (Maguire & Slater 2010). Ageing is genetically programmed and influenced by the environment, so the rate of ageing among people varies widely (Cheitlin 2003). Ageing is characterized by a general deterioration of bodily function. Although ageing is considered to be inevitable, the reality is that the rate of deterioration in organ function can be reduced by factors such as regular exercise and accelerated by habits such as cigarette smoking and heavy alcohol consumption. Indeed, there is considerable variability in individuals’ susceptibility to ageing. Table 22.1 outlines some of the organ and tissue changes associated with ageing, which will underpin patient assessment.

Table 22.1

Physiological changes associated with ageing

Adapted from Stevenson J (2004) When the trauma patient is elderly. Journal of Peri Anaesthesia Nursing, 19(6), 392–400.

Assessment

An older person presenting to the ED requires a thorough physical, psychological and social assessment. Good communication is vital and the emergency nurse must have the ability to listen effectively. As older people’s hearing and vision may be impaired and their responses slow, it is important to give the patient time to express themselves freely. It is also important to remember that the history-taking process may take longer than the physical examination, and studies indicate that over 80 % of diagnoses are based on the interview alone (Epstein et al. 2003). Patients have previously expressed concerns about lack of assessment and information-giving (Considine et al. 2010). Older people can present with multiple pathologies and the presenting complaint may not be the only condition that needs to be considered.

The emergency nurse needs to elicit why the person has attended the ED. The assessment can begin with a general question that allows full freedom to respond; for example, ‘What brings you here?’ or ‘What can we do for you?’ After the patient answers, probe further by asking ‘Is there anything else?’ It is imperative to remember that patients may also have complex psychological and social causes and may have complicated feelings about themselves, their illnesses or potential treatments. To gain a thorough history, which fulfils the patient expectations, the interviewing technique must allow patients time to recount their own stories spontaneously (Bickley & Szilagyi 2003). An example of how to structure history taking is provided in Table 22.2.

Table 22.2

| Location | Where is the pain/problem? |

| Timing/onset | When did it start? When did you last feel well? Did it start suddenly or gradually? |

| Quality | How does the patient describe the pain? Is it constant or intermittent? |

| Quantity or severity | How does this problem affect their daily living, e.g., shortness of breath, can they walk as far as normal, can they do the stairs? |

| Aggravating factors | Does anything make it worse? |

| Relieving factors | Does anything make it better? |

| Associated manifestations | Are there any other symptoms, e.g., if they are short of breath do they also have a cough? |

When first meeting the patient, the nurse should introduce themselves, both as a courtesy and as an opportunity to establish a rapport. If the patient has walked into the department, the nurse should accompany the patient to the cubicle and observe features such as gait, balance and pace.

Not all patients attending the ED require a full set of vital signs and the older person must be assessed individually. For many patients, vital signs will form an integral part of the patient assessment. Older people may have altered vital signs that are normal for them; however, it is imperative to establish their normal baseline. This can be gained from the patient or relative, the computer record system or the patient’s Single Assessment Process document (Department of Health 2001a). For example, the heart rate of an older person is likely to be slower, with arrhythmias being relatively common in otherwise asymptomatic patients. Similarly, the older person’s blood pressure is likely to be elevated, usually as a consequence of atherosclerosis. This predisposes the patient to the development of cardiovascular diseases, such as congestive cardiac failure, stroke, transient ischaemic attacks and dementia. If a normally hypertensive patient appears to have a normal blood pressure they may actually be hypotensive. Similarly, if the patient is prescribed and taking beta-blockers they will fail to have a tachycardic response to shock, so the emergency nurse must apply knowledge of pharmacology and altered physiology when analyzing vital signs.

Elder abuse

Elder abuse, although increasingly recognized as a violation of human rights, remains one of the most hidden forms of inter-family conflict within many societies (Podnieks et al. 2010, Naughton et al. 2012).

The prevalence of elder abuse in the UK is estimated to be 2.6 % (Biggs et al. 2009) although international studies range from 2.1 % in Ireland (Naughton 2011), to 9–11.4 % in the US (Lauman et al. 2009, Lowenstein et al. 2009), which raises several questions. Are the differences related to cultural/societal factors or study design factors or in the risk factors for elder abuse? Nurses should have a high index of suspicion when assessing older people, as with non-accidental injury in children. Clinicians must assess whether the mechanism is consistent with the injury or illness presented (Crouch 2003) as cognitive impairment limits older adults’ abilities to advocate for themselves and possibly heightens their risk for abuse (Ziminski et al. 2012). If emergency nurses know the red flags of abuse (Box 22.2), the right questions to ask (Boxes 22.3 and 22.4) and the appropriate action to take in cases of suspected abuse, they can make a critical difference to the welfare of an older person (Gray-Vickery 2005). As Phelan (2012) notes nurses in the ED should be cognizant of interviewing the older person on their own when collecting information, as he may be hugely compromised with the presence of a family member who may be the perpetrator. It is also useful to interview the accompanying relative separately to elicit the cause of attendance, which may deviate from the older person’s account. In the context of a relative refusing to leave, it should be noted and the older person should be facilitated to answer the questions rather than being dominated by the relative/other person. This is also why it is essential to build up rapport with the patient to enable to older person to disclose. If nurses suspect abuse, attention to detail when documenting is of paramount importance. Document the person’s account in their own words (Community and District Nursing Association 2003) and signs of abuse clearly, and consider the use of illustration through medical photography; this requires specialist consent and adherence to local protocols. Upon detection of abuse local guidelines and policies should be adhered to.

Polypharmacy

The use of multiple medications (polypharmacy) is common among older people (Linton et al. 2007, Zarowitz 2011). This is caused by many factors, such as co-existing chronic conditions, use of more than one pharmacy, increase in the availability of over-the-counter medicines and multiple prescribing providers. Indeed, interviews carried out with multi-professionals reported that participants admitted that prescribing was sometimes inappropriate and prescribing for chronic diseases was poorly understood (Spinewine et al. 2005). A US study indicated that 23 % of women and 19 % of men take at least five prescription drugs (Kaufmann et al. 2002). These figures, however, do not take into account medication purchased over the counter.

The effects of polypharmacy may have precipitated the patient’s attendance at the ED. Falls and dehydration are common risk factors associated with multiple medications (Department of Health 2001b). Emergency nurses need to be aware of medicine-related features, which are known to be associated with problems in older people. These are:

• taking four or more medications

• specific medications, e.g., warfarin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), diuretics and digoxin

Social and personal factors associated with medication-related problems are:

• social support – minimal support available

• physical condition – poor hearing, vision and dexterity

• mental state – delirium/dementia (Department of Health 2001a).

Patients presenting with polypharmacy should have a detailed drug history recorded; it is good practice to have a pharmacist review medications during the patient’s ED episode. However, if this service is unavailable, careful attention should be given to taking and documenting the drug history. In addition to the drug name, dose and frequency, the source of the history, compliance and concordance should be noted. The key to ensuring safety is appropriate prescribing and monitoring of the patient’s condition; 5–17 % of preventable admissions are associated with adverse reactions to medications (Department of Health 2001a). Prescribing should take into account the physiology of ageing, drug interactions, cautions, side-effects and the recommended dose for older people.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia is classified as a core temperature below 35°C; it is associated with a high mortality rate among older people. Three types of accidental hypothermia are recognized. Acute hypothermia (often called immersion hypothermia) is caused by sudden exposure to cold such as immersion in cold water or a person caught in a snow avalanche. Exhaustion hypothermia is caused by exposure to cold in association with lack of food and exhaustion such that heat can no longer be generated. Chronic hypothermia comes on over days or weeks and mainly affects the elderly (Guly 2010). It is important to ascertain whether hypothermia is caused by environmental exposure or is a consequence of unknown pathology. Common precipitants include immobility (Parkinson’s disease, hypothyroidism), reduced cold awareness (dementia), unsatisfactory housing, poverty, drugs, alcohol, acute confusion and infections (Wyatt et al. 2005). Malnutrition may also be a leading factor associated with hypothermia. A well-balanced diet is essential to provide the calories needed to generate and maintain adequate heat. A decrease in calorie intake can have a profound effect on the ability to produce heat by shivering (Neno 2005).

Physiology

Body temperature is regulated in the anterior hypothalamus. In cold weather, when the body needs to conserve heat, the hypothalamic heat production centres respond to impulses from the thermoreceptors by causing peripheral vasoconstriction via the sympathetic nervous system. This vasoconstriction enhances the insulating properties of the skin, reducing blood flow to the superficial vessels; the result is less heat being lost from the skin (Pocock & Richards 2004).

The ability of people to respond appropriately to changes in the ambient temperature decreases with age. There is a reduction in the awareness of temperature variances and of thermoregulatory responses. Many older people are unable to discriminate a difference between 2.5 and 5°C (Pocock & Richards 2004). When vasoconstriction fails to raise the body temperature, heat is produced by shivering. However, this response is reduced in older people (Box 22.5).

Assessment

Assessment should begin with airway, breathing, circulation and disability; immediate intervention is required if the patient is not breathing or has an absent pulse, when advanced life support should be commenced (Nolan et al. 2010).

A 12-lead ECG should be recorded and patients with a core temperature <35°C should have continuous cardiac monitoring because of the risk of dysrhythmia or ischaemic changes. The ECG may show a bradycardia or atrial fibrillation: however, in severe hypothermia the ECG may show J waves that occur at the junction of the QRS complex and the ST segment (Haslett et al. 2002). The J wave is a specific finding in hypothermia that disappears when the temperature begins to return to normal (Manning & Stolerman 1993).

Management

Re-warming may be passive external, active external or active internal (core re-warming). Patients should be re-warmed at a rate that corresponds with the rate of onset of hypothermia (Nolan et al. 2010). In reality this is difficult to gauge. Re-warming should not exceed increases of 0.3–1.2°C per hour in mild hypothermia; however, in severe cases rapid re-warming of 3°C per hour is essential (Carson 1999). Hypothermic patients should be handled carefully; vigorous procedures such as tracheal intubation can precipitate VF (Nolan et al. 2010).

In mild cases it is sufficient to remove the patient from the cold environment, and prevent further heat loss by wrapping the patient up warmly and providing hot drinks in a warm environment (passive warming). In all cases of hypothermia the removal of wet/soiled clothing should be undertaken as soon as possible, and the patient should be dried and covered with blankets. The patient’s head should also be covered, as up to 40 % of body heat is lost through the scalp. In moderate cases active external methods should be used which include heated pads that lie beneath the patient, or warm air-filled blankets (Holtzclaw 2004). In severe cases active external methods may include the use of warm humidified gases, and gastric, peritoneal, pleural and bladder lavage with warm fluids at 40°C (Nolan et al. 2010).

In hypothermic cardiac arrest the patient requires circulation, oxygenation and ventilation while the core body temperature is gradually raised; this is best achieved by active internal re-warming using cardiopulmonary bypass. Where this facility is unavailable, continuous veno-venous haemofiltration and warming replacement fluids can be used. Death should not be confirmed until the patient has been rewarmed, or until warming attempts have failed to raise the core temperature (Resuscitation Council (UK) 2005).

During the re-warming phase the emergency nurse must be aware that:

• the patient may become hypotensive as the vascular space expands due to vasodilatation. Patients are therefore likely to require large volumes of fluid. Older people are at greater risk of pulmonary oedema; patients therefore require careful haemodynamic monitoring via arterial blood pressure and central venous pressure and should be transferred to a critical-care environment following the ED episode

• peripheral vasodilatation may cause the core body temperature to drop

• arrhythmias may occur but tend to revert spontaneously (other than VF) and do not require treatment

• rapid metabolic changes can occur and should be monitored closely; hyperkalaemia may occur (Nolan et al. 2010).

Following an episode of hypothermia, it will be essential to prevent a recurrence. An in-depth multi-professional assessment, including occupational therapist, nutritionist and social worker, which addresses the predisposing factors that led to the admission is required. Only patients who have had a mild case of hypothermia, i.e., above 34°C, may be discharged following preventive advice. Those with lower core temperatures will require admission. Although increasing severity of hypothermia does worsen prognosis, the major determinant of outcome is the precipitating illness or injury. Reported mortality rates vary from 0–85 % (Rogers 2004).

Delirium

Confusion in older people is a catchall term that covers both dementia and delirium, but may also be a consequence of depression. They are, however, quite different. Dementia is a long-term, non-reversible loss of both short- and long-term memory. Delirium (sometimes called ‘acute confusional state’) is a common clinical syndrome characterized by disturbed consciousness, cognitive function or perception, which has an acute onset and fluctuating course. It usually develops over 1–2 days. It is a serious condition that is associated with poor outcomes. However, it can be prevented and treated if dealt with urgently (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2010). The prevalence of older people attending the ED with delirium is 10–12 % (Hustey & Meldon 2002).

The ED nurse has an important role in the detection and management of patients with acute delirium. A study by Hustey & Meldon (2002) found that the mental impairment detection rate by emergency doctors was between 28 and 35 % and those discharged with delirium had very little discharge advice or follow-up arranged. Information received from the ambulance crew, relatives, home wardens and neighbours can also be crucial in determining the onset and degree of delirium in the patient. This information will be helpful in determining the patient’s health and mental status prior to their arrival in the ED.

The aetiology of delirium has to be determined from the history, physical examination and special investigations. This creates a real challenge for emergency nurses, as the history and symptoms can be atypical (Table 22.3); however, linked to knowledge of the altered physiology of ageing, the underlying cause will be found through appropriate investigations.

Table 22.3

Disorders presenting with atypical features in older people

| Disorder | Atypical presentation |

| Myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolism | Confusion, collapse, breathlessness and palpitations without chest pain |

| Bronchopneumonia | Confusion, tachypnoea, minimal chest signs, no pyrexia |

| Appendicitis | Confusion and constipation or diarrhoea, few localizing signs and no pyrexia |

| Peptic ulcer | Anaemia, haematemesis or melaena without symptoms of dyspepsia |

| Urinary tract infection | Confusion and urinary incontinence without pyrexia, dysuria or frequency |

| Dehydration | No thirst, skin changes indistinguishable from those of ageing |

| Diabetes mellitus | Asymptomatic until onset of complications, nephropathy, neuropathy or retinopathy |

| Hypothyroidism | Lethargy and general deterioration with no other characteristic signs and symptoms |

| Thyrotoxicosis | Apathy, weight loss and cardiac signs without anxiety, excess sweating or heat tolerance |

| Brain tumour | Confusion, drowsiness and focal neurological signs without headache or papilloedema |

(Adapted from Edwards CRW, Bouchier IAD, Haslett C (1995) Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. London: Churchill Livingstone.)

Assessment

Delirium can result from a pathological lesion within the brain or acting on the brain from a focus elsewhere in the body such as a urine or chest infection. Rapid onset indicates an acute problem. It is therefore important to elicit the timeframe for the development of delirium; information can be gleaned unobtrusively from observing and interacting with the patient. The nurse should note the following:

• does the patient respond appropriately to questions?

• are the patient’s clothes soiled?

• orientation to time, place and person and situation should also be assessed.

Physical examination will provide clues to the cause of the confusional state. Mental function may be impaired in varying degrees; impaired conscious level is a hallmark symptom of delirium. It is important to exclude hypoxia at this point. Observe the patient’s work of breathing; checks for cyanosis and vital signs should include a respiratory rate and oxygen saturation monitoring. Temperature, blood pressure, pulse and respirations should be taken to assess for signs of infection, such as urinary tract and chest infections, which are common causes of delirium in older people (Box 22.6). Simple diagnostic tests such as urinalysis will help to identify potential causes. Evidence of dehydration will often be present in the confused, older person. The nurse should observe mucous membranes, skin turgidity and vital signs, as significant dehydration may be the cause of the confusional state. In addition, hypothermia, myocardial infarction, stroke and metabolic disorders such as diabetes mellitus (Table 22.3) may also present as acute confusion; it is therefore necessary to check the patient’s blood sugar, record and analyse a 12-lead ECG and monitor oxygen saturation levels. Blood screening for infections or metabolic causes should also be undertaken. A chest X-ray may confirm a chest infection.

Stroke

Stroke mostly occurs in elderly people; patient outcomes after stroke are highly influenced by age, with over 80 % of strokes occurring in people over 65 years of age (Chen et al. 2010). Stroke is ranked as the second most common single cause of death in the developed world after ischaemic heart disease (Di Carlo 2009). It is also the largest cause of adult disability with up to half of all patients who survive a stroke failing to regain independence and needing long-term healthcare (Sturm et al. 2004).

A stroke is defined as a focal neurological deficit due to a vascular lesion that has a rapid onset and lasts longer than 24 hours (Kumar & Clark 2002). Approximately 150 000 people in England have a stroke every year and a further 20 000 people have a transient ischaemic attack (TIA), which is defined as stroke symptoms and signs that resolve within 24 hours (NICE 2008).

Physiology

Brain tissue is particularly sensitive to the effects of oxygen deprivation, and the effect of occlusion of any part of the vasculature depends on the vessel involved, the collateral blood supply and the duration of occlusion. There are two mechanisms of cerebral injury: cerebral infarction (80 %) and intracerebral haemorrhage (20 %) (Wyatt et al. 2005). Cerebral infarction is most likely to occur from a thromboembolism secondary to atherosclerosis in the carotid artery and aortic arch (Pocock & Richards 2004). However, this can also be caused by an embolism from atrial fibrillation, valve disease or following a myocardial infarction. Intracerebral haemorrhage is caused by an entry of blood into the brain, which immediately stops function in the area as the neurones are disrupted (Pocock & Richards 2004). This may be caused by hypertension, bleeding disorders and intracranial tumours (Wyatt et al. 2005). Older people who have a stroke are more likely to have an other underlying pathology such as COPD, ischaemic heart disease, visual impairments and renal failure; these co-morbidities must be considered at the time of assessment.

Assessment

The correct diagnosis must be made through careful history-taking, physical examination and investigations. An acute focal stroke is characterized by a sudden appearance of a focal deficit, most commonly a hemiplegia, with or without aphasia, hemi-sensory loss or visual field defect (Haslett et al. 2002).

Classifications of a focal stroke:

• transient if the deficit disappears in 24 hours; however, 20 % of these patients will have a stroke within the first month; they are most at risk within the first 72 hours (Royal College of Physicians 2004)

• completed if the deficit persists but does not worsen

• evolving if the deficit continues to worsen after 6 hours (Haslett et al. 2002).

The nursing assessment must commence with airway, breathing, circulation and disability. If the patient is unconscious, resuscitate as per guidelines, otherwise assess the airway for patency as the patient may have difficulty protecting their own airway (Haslett et al. 2002). Open the patient’s airway using manual manoeuvres and inspect for foreign bodies, vomit and suction as necessary. If this is successful insert an oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal adjunct and administer oxygen. If the patient tolerates an airway, the patient will require a definitive airway and the nurse must call for a senior clinician and anaesthetic support.

Assess breathing by observing the rate, rhythm, depth and effort of breathing and monitor oxygen saturation levels. People who have had a stroke should receive supplemental oxygen only if their oxygen saturation drops below 95 %. The routine use of supplemental oxygen is not recommended in people with acute stroke who are not hypoxic (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2008). Chest auscultation may detect underlying pathology and the patient may require a chest X-ray.

To assess circulation record the patient’s temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, blood sugar level and an ECG, particularly looking for atrial fibrillation. Hypertension is commonly noted following a stroke; the only indication for lowering blood pressure in the acute phase is if the patient is at risk of complications of hypertension, e.g., hypertensive encephalopathy, aortic aneurysm and renal involvement (Royal College of Physicians 2004, Peters 2009). Blood pressure should return to normal within 24–48 hours spontaneously (Haslett et al. 2002). Intravenous access should be gained and bloods taken for full blood count, U&E and a clotting screen if the stroke is suspected to be caused by a bleeding disorder. Patients should have their gag reflex assessed by a trained professional; until this is completed the patient should receive intravenous fluids. Extent of any disability is assessed by recording a full Glasgow Coma Scale.

Management

The emergency nurse must possess knowledge of the medical treatment options to influence care and to support the patient and relatives. The nurse must monitor the patient closely to observe for signs of an evolving stroke and this must be communicated to the medical staff. The neurological assessment should include documentation of the localized signs and brain imaging should be carried out as soon as possible or within 24 hours of the onset. If the pathology or the diagnosis of a stroke is uncertain, an MRI scan should be considered (Royal College of Physicians 2004).

The fundamental approaches to acute ischaemic stroke therapy are reperfusion and neuroprotection, with early reperfusion being the most effective therapy. Early clot lysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) up to three hours after ischaemic stroke improves patients’ outcomes (Green 2008, Chen et al. 2010). A haemorrhagic stroke must be excluded, and the patient must not be hypertensive. This procedure must be carried out by specialist staff.

Antithrombolytic treatment can be started when a primary haemorrhage has been excluded. Aspirin 300 mg should be given rectally if the patient is dysphagic. Anticoagulation is only necessary if the embolism is from the heart caused by atrial fibrillation; these patients will require oral anticoagulation with warfarin (Haslett et al. 2002).

The Royal College of Physicians (2004) report that surgical evacuation of a primary intracerebral haemorrhage is not supported by evidence. However, they suggest cases of supratentorial haemorrhage with mass effect should be considered for surgical intervention. They recommend that urgent neurosurgical opinion be sought.

Falls

Falls are the commonest cause of accidental injury in older people, the commonest cause of presentation to urgent care (Kenny et al. 2013, Banerjee et al. 2012) and the commonest cause of accidental death in the 75-plus population. About 6 % of falls in those over 65 result in a fracture, including 1 % being of the hip. Having fallen is the commonest reason for older people to attend the ED and for being admitted to hospital. Injury occurs more commonly in frailer persons and the nature of the fall affects injury risk and type. Falls due to syncope are particularly likely to result in injury including facial bruising. In more active and younger people, wrist fractures are more common whereas from 75 plus, hip fractures predominate (British Geriatric Society 2007). Traumatic injury caused by falls is the most common surgical reason for presentation to the ED by an older person (Aminzadeh & Dalziel 2002).

Falls can result from the interaction of multiple intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Common intrinsic factors include a history of a previous fall, visual disorders, arthritis, confusion, balance impairment, muscle weakness, sensory impairment and polypharmacy (Tideiksaar 2003, Sudip et al. 2004). Extrinsic factors include environmental hazards such as poor lighting, slippery floors and lack of bathroom rails (Tideiksaar 2003). As a consequence, older people are more likely to sustain falls than younger individuals. Illnesses such as cardiac disease, diabetes and sepsis also contribute to the incidence of falls in older people, as do medications such as diuretics, hypnotics and antihypertensive drugs, due to their hypotensive side-effects (Department of Health 2001a).

The emergency nurse must again assess the older person systematically; airway, breathing, circulation, disability and exposure must be assessed. It is important to ensure that the presentation is caused by a mechanical fall and not by a collapse caused by syncope, postural hypotension, visual problems, polypharmacy or carotid sinus syndrome (British Geriatric Society 2003). Physical examination should include an assessment of standing balance and gait; vital signs should include lying and standing blood pressure, blood sugar monitoring, urinalysis and a 12-lead ECG. Any subsequent investigations may be required dependent on clinical findings.

The emergency nurses’ role is pivotal to ensuring that the ED assessment is comprehensive and includes a full social history. A study by Bentley & Meyer (2004) found that the most likely reason for re-attendance at the ED after direct discharge was a fall. In those identified cases, adequate assessment of the patients’ social and functional needs was not done and the impact of illness or injury underestimated when considering their ability to cope on discharge.

A risk assessment of the older person prior to discharge should include:

• medical conditions – a thorough history and examination to exclude underlying pathology and problems associated with polypharmacy which may have caused the fall. If an underlying medical condition is the cause of the fall the patient is likely to require admission to hospital. A full social history must be documented as part of this process

• mobility – their ability to walk unaided, with a stick or Zimmer frame, but without carer support, is an important determinant of fitness for discharge. Assessment should be carried out with a multi-professional team

• social support – it is important to establish whether the older person lives alone or has formal or informal support available or whether the ED nurse needs to start coordinating these services in collaboration with primary care

• lifestyle – consider whether the injury incurred will enable the older person to function: for example, in a patient who lives alone but has a fractured wrist, an OT assessment should be considered

• external influences – those living alone in a tower block without working lifts will find it more difficult to mobilize than someone living in sheltered accommodation. The handover ambulance crew can often provide useful information about the environment to which the patient may be returning.

The greatest risk indicator for a future fall is a history of a fall; therefore the assessment and discharge process must be rigorous. There are several tools available; most agree that two predictive risk indicators are a history of falls and polypharmacy (Tideiksaar 2003, Sudip et al. 2004) (Box 22.7). However, remember that seemingly minor infections can cause a fall in older people.

Fractured neck of femur

Fractured neck of femur (hip) is the most serious consequence of falls among older people, with a post-operative mortality rate of 5–10 % at 30 days and 19–30 % one year after a fall (Roche et al. 2005, Braur et al. 2009, Wiles et al. 2011). Around 20 % of patients require institutional care at discharge (Roberts et al. 2004). Recurrent falls are associated with increased mortality, increased rates of hospitalization, curtailment of daily activities and higher rates of institutionalization. Osteoporosis affects 1 in 3 women and 1 in 12 men over the age of 50 years and almost half of all women experience an osteoporotic hip fracture by the age of 70 years (Department of Health 2001a). Over 300 000 patients present to hospitals in the UK with fragility fractures each year, with medical and social care costs – most of which related to hip fracture care – at around ≤2bn. Current projections in the UK suggest that hip fracture incidence will rise from 70 000 per year in 2007 to 91 500 in 2015 and 101 000 in 2020 (British Orthopaedic Association 2007).

Classical features associated with a fractured neck of femur are:

Management

Emergency nurses should utilize an integrated care pathway where it exists: this will facilitate a seamless assessment, treatment and referral process for the patient. Ninety per cent of patients should be admitted in two hours and 100 % within four hours (Department of Health 2006). Patients will require pressure-area care in the ED and consideration should be given to ordering a pressure-relieving mattress.

Analgesia is extremely important in the treatment of hip fractures as pain is likely to be the patient’s main problem. Patients with dementia/delirium or cognitive impairment receive less analgesia than those who do not have any cognitive impairment (Heyburn et al. 2000). It is therefore imperative that the emergency nurse is sensitive to subtle non-verbal signs of pain. It must also be remembered that the patient may be pain-free at rest but will have to move for the X-ray and ultimate transfer to a ward or theatre. Analgesia should be administered in accordance with local policy within 20 minutes of arrival; however, greatest efficacy is usually achieved by intravenous opiates titrated to pain; an anti-emetic drug should also be administered.

Conclusion

Crouch (2012) has astutely described the elderly as ‘the most complex, challenging and rewarding to care for within the emergency department’. This chapter has covered the physiological effects of ageing, and some of the common presenting complaints associated with older people.

As demographic changes in the population continue to evolve, emergency nurses are required to ensure they have the appropriate knowledge and skills to provide older people with the highest standard of care. The assessment of older people, because of their social, psychological and physical vulnerability, is a critically important dimension of care in the ED; however, older people should not be seen as a homogeneous group who are all victims or who are automatically infirm because of their age. The ED nurse has an opportunity to challenge stereotypes, provide health promotion and offer guidance on services available to older patients, as well as acting as an advocate for those unable to communicate for themselves. It presents a challenge which ED nurses should embrace as part of their role as health professionals.

References

Action on Elder Abuse. Indicators of Abuse. London: Action on Elder Abuse; 2005.

Aminzadeh, F., Dalziel, W.B. Older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes and effective interventions. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2002;39:238–247.

Association of Community Health Councils of England and Wales. Nationwide Casualty Watch. London: ACHEW; 2001.

Banerjee, J., Conroy, S., O’Leary, V., et al. Quality care for older people with urgent or emergency care needs (‘Silver Book’). London: British Geriatrics Society; 2012.

Bentley, J., Meyer, J. Repeat attendance by older people at accident and emergency departments. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;48(2):149–156.

Beynon, T., Gomes, B., Murtagh, F.E.M., et al. How common are palliative care needs among older people who die in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2011;28:491–495.

Bickley, L.S., Szilagyi, P.G. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking, eighth ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Company; 2003.

Biggs, S., Manthorpe, J., Tinker, A., et al. Mistreatment of older people in the United Kingdom: Findings from the First National Prevalence Study. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. 2009;21:1–14.

Brauer, C.A., Coca-Perraillon, M., Cutler, D.M., et al. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302:1573–1579.

Bridges, J., Meyer, J., Dethick, L., Griffiths, P. Older people in accident and emergency: implications for UK policy and practice. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology. 2005;14:15–24.

British Geriatric Society. Standards of Medical Care for Older People: Expectations and Recommendations. London: British Geriatric Society; 2003.

British Geriatric Society. Falls. London: British Geriatric Society; 2007.

British Orthopaedic Association. The care of patients with fragility fracture. London: BOA; 2007.

Carson, B. Successful resuscitation of a 44 year old man with hypothermia. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 1999;25(5):356–360.

Cheitlin, M.D. Cardiovascular physiology: Changes with ageing. American Journal of Geriatric Cardiology. 2003;12(1):9–13.

Chen, R.L., Balami, J.S., Esiri, M.M., et al. Ischemic stroke in the elderly: a review of the evidence. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2010;6:256–265.

Clark, M.J., Fitzgerald, G. Older people’s use of the ambulance service, a population based analysis. Journal of Accident and Emergency Medicine. 1999;16:108–111.

Community and District Nursing Association. Responding to Elder Abuse. London: CDNA; 2003.

Considine, J., Smith, R., Hill, K., et al. Older peoples’ experience of accessing care. International Emergency Nursing. 2010;13:61–69.

Crouch, R. Emergency care of the older person. In: Jones G., Endacott R., Crouch R., eds. Emergency Nursing Care, Principles and Practice. London: GMM, 2003.

Crouch, R. The older person in the emergency department: seeing beyond the frailty. International Emergency Nursing. 2012;20(4):191–192.

Department of Health. National Service Framework for Older People. London: Department of Health; 2001.

Department of Health. National Service Framework for Older People. Medicines and Older People, Implementing Medicines-related Aspects of the NSF for Older People. London: Department of Health; 2001.

Department of Health. Delivering Quality and Value. London: Department of Health; 2006.

Di Carlo, A. Human and economic burden of stroke. Age and Ageing. 2009;38:4–5.

Duffy, R., Neville, R., Staines, H. Variance in practice emergency medical admission rates: can it be explained? British Journal of General Practice. 2002;52(474):14–17.

Edwards, C.R.W., Bouchier, I.A.D., Haslett, C. Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1995.

Epstein, O., Perkins, D.G., Cookson, J., De Bono, D.P. Clinical Examination, third ed. London: Mosby; 2003.

Gray-Vickery, P. Elder abuse: are you prepared to intervene? LPN. 2005;1(2):38–42.

Green, A.R. Pharmacological approaches to acute ischaemic stroke: reperfusion certainly, neuroprotection possibly. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;153((Suppl 1):S325–S338.

Guly, H. History of accidental hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2010;82(1):122–125.

Haslett, C., Chilvers, E.R., Boon, N.A., Colledge, N.R. Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine, nineteenth ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2002.

Health Advisory Service. (1998) Not because they are old: An independent inquiry into the care of older people on acute wards in general hospitals. London: HAS (2000); 2000.

Heyburn, G., Jenkinson, M., Beringer, T., et al. The efficiency of analgesia in the elderly hip fracture patient. Age Ageing. 2000;29(Suppl 1):26.

Higgins, I., Slater, L., Van der Riet, P., et al. The negative attitudes of nurses towards older patients in the acute hospital setting: a qualitative descriptive study. Contemporary Nurse. 2007;26(2):225–238.

Holtzclaw, B. Shivering in acutely ill vulnerable populations. Advanced Practice in Acute Clinical Care. 2004;15(2):267–279.

Hustey, F.M., Meldon, S.W. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2002;39:248–253.

Kaufman, D.W., Kelly, J.P., Rosenberg, L., et al. Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the United States: The Slone survey. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287(3):337–344.

Kenny, R.A., Romero-Ortuno, R., Cogan, L. Falls. Medicine in Older Adults. 2013;41(1):24–28.

Klein Schmidt, K.C. Elder abuse: a review. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1997;30(4):463–472.

Kumar, P., Clark, M. Clinical Medicine, fifth ed. London: WB Saunders Co; 2002.

Laumann, E.O., Leitsch, S.A., Waite, L.J. Elder mistreatment in the United States: Prevalence Estimates From a Nationally Representative Study. Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2009;63B:S248–S254.

Linton, A., Garber, M., Fagan, N.K., et al. Examination of multiple medication use among TRICARE beneficiaries aged 65 years and older. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 2007;13(2):155–162.

Lowenstein, A., Eisikovits, Z., Band-Winterstein, T., et al. Is elder abuse and neglect a social phenomenon: Data from the First National Prevalence Survey in Israel. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. 2009;21:253–277.

Maguire, S.L., Slater, B.M.J. Physiology of ageing. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine. 2010;11(7):290–291.

Majeed, A., Bardsley, M., Morgan, D., et al. Cross-sectional study of primary care groups in London: association of measures of socioeconomic and health status with hospital admission rates. British Medical Journal. 2000;321(7268):1057–1060.

Manning, B., Stolerman, D.F. Hypothermia in the elderly. Hospital Practice. 1993;28(5):53–70.

Meyer, J., Bridges, J. An Action Research Study into People in the A&E Department. London: City University; 1998.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Stroke: Diagnosis and initial management of acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA). London: NICE; 2008.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Delirium: Diagnosis, prevention and management. London: NICE; 2010.

Naughton, C., Drennan, J., Treacy, P., et al. The role of health and non-health-related factors in repeat emergency department visits in an elderly population. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2011;27:683–687.

Naughton, C., Drennan, J., Lyons, I., et al. Elder abuse and neglect in Ireland: results from a national prevalence study. Age and Ageing. 2012;48(1):98–103.

Neno, R. Hypothermia: assessment, treatment and prevention. Nursing Standard. 2005;19(20):47–52.

Nikki, L., Lepistö, S., Paavilainen, E. Experiences of family members of elderly patients in the emergency department: A qualitative study. International Emergency Nursing. 2012;20(4):193–200.

Nolan, J.P., Hazinski, M.F., Billi, J.E., et al. International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Part 1: Executive Summary. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1219–1276.

Office of National Statistics. Population Trends. London: ONS; 2006.

Office of National Statistics. Population Figures. London: ONS; 2009.

Peters, M.L. The older person in the emergency department: Aging and atypical illness presentation. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2009;36(1):29–34.

Phelan, A. Elder abuse in the emergency department. International Emergency Nursing. 2012;20(4):214–220.

Pocock, G., Richards, C.D. Human Physiology. The Basis of Medicine, second ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004.

Podnieks, E., Anetzberger, G.J., Wilson, S.J., et al. World view environment scan on elder abuse. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. 2010;22:164–179.

Purdy, S. Avoiding hospital admissions: What does the research evidence say?. London: The King’s Fund; 2010.

Purdy, S., Griffin, T., Salisbury, C., et al. Emergency admissions for chest pain and coronary heart disease – A cross-sectional study of general practice, population and hospital factors in England. Public Health. 2011;125:46–54.

Resuscitation Council (UK). Resuscitation Guidelines. London: Resuscitation Council (UK); 2005.

Roberts, H.C., Pickering, R.M., Onslow, E., et al. The effectiveness of implementing a care pathway for femoral neck fracture in older people: a prospective controlled before and after study. Age and Ageing. 2004;33:178–184.

Roche, J.J.W., Wenn, R.T., Sahota, O., et al. Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: prospective observational cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2005;33:1374.

Rogers, I. Hypothermia. In Cameron P., Jelinek G., Kelly A.M., et al, eds.: Textbook of Adult Emergency Medicine, second ed, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

Royal College of Physicians. National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke, second ed. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2004. [Prepared by the Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party].

Sowney, R. Older People in Accident and Emergency, a position statement. Emergency Nurse. 1999;7(6):6–7.

Spilsbury, K., Meyer, J., Bridges, J., et al. The little things count. Emergency Nurse. 1999;7(6):24–31.

Spinewine, A., Swine, C., Dhillon, S., et al. Appropriateness of use of medications in elderly inpatients: qualitative study. British Medical Journal. 2005;331:935–940.

Stevenson, J. When the trauma patient is elderly. Journal of Peri Anaesthesia Nursing. 2004;19(6):392–400.

Sturm, J.W., Donnan, G.A., Helen, M., et al. Quality of life after stroke: the North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Stroke. 2004;35:2340–2345.

Sudip, N., Parsons, S., Cryer, C., et al. Development and preliminary examination of the predictive validity of the Falls Risk Assessment Tool for use in primary care. Journal of Public Health. 2004;26(2):138–143.

Tideiksaar, R. Best practice approach to fall prevention in community-living elders. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2003;19(3):199–205.

Wiles, M.D., Moran, C.G., Sahota, O., et al. Nottingham Hip Fracture Score as a predictor of one year mortality in patients undergoing surgical repair of fractured neck of femur. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2011;106(4):501–504.

Wyatt, J.P., Illingworth, R.N., Clancy, M.J., et al. Oxford Handbook of Accident and Emergency Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Zarowitz, B.J. Polypharmacy: When is enough, enough? Geriatric Nursing. 2011;32(6):447–449.

Ziminski, C.E., Phillips, L.R., Woods, D.L. Raising the index of suspicion of elder abuse: Cognitive impairment, falls, and injury patterns in the emergency department. Geriatric Nursing. 2012;33(2):105–112.