6 Older people

Presentation of disease in older people

Two major factors influence the recognition of disease processes in older people:

The acceptance of ill health and disease as ‘ageing’, with its resultant disabilities, means that many older people expect to be frail, rarely complain and often seek help late. Coming to terms with some disability or change is necessary at all ages, and acceptance is part of survival. However, the tacit acceptance of inevitable deterioration – for example in vision, hearing, teeth and feet – may lead to treatable conditions being ignored and result in loss of independence. Table 6.1 illustrates what may be regarded as normal ageing and what is pathological.

| System | Normal ageing | Pathophysiological changes common in older age |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular |

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; FVC, forced vital capacity; GI, gastrointestinal; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LH, luteinizing hormone; PEFR, peak expiratory flow rate.

The range of presentation of disease in old age is an essential element for the student and practitioner to comprehend. The term ‘geriatric giants’ (Box 6.1) refers to a set of symptoms and signs that occur in old age which may have as their cause many different disease processes. In normal day-to-day circumstances, ageing organs are able to maintain normal metabolic function. However, when major stressors are experienced, as in acute illness, functional capacity is exceeded and rapid clinical deterioration may occur. In the elderly patient, multiorgan failure may develop rapidly in the context of illness, especially infections. Another important concept is that of multiple comorbidities, which may be causally linked, although more typically they are not. Iatrogenic illness, most commonly due to polypharmacy, often exacerbates disability in the older person.

History

There are several universal practical points in the way the history is approached which are particularly important when taking a history from an older patient (Box 6.2). The first contact is extremely important (Box 6.3). Eye contact, a greeting, an outstretched hand (expecting a returned handshake), your name and the purpose of the meeting are all that are required to begin with. These relatively simple gestures can provide a wealth of information in the first few minutes. Depressed and very anxious patients may avoid eye contact. The handshake is often revealing. Some patients with dementia may not respond, not recognizing the meaning of the social gesture. Frightened older patients may continue to clutch one’s hand. Giving your name and purpose puts people at ease and can also be used later to assess short-term memory. Ask the person ‘What is your name?’ Be alert for hearing impairment. The reply will indicate how a person wishes to be addressed; alternatively, the patient may be specifically asked this.

The social history and social networks

The social history has extra significance in older people. Routine questions regarding occupation, smoking and alcohol are often forgotten, but should provide a familiar stepping stone to discussing the patient’s home, how he is managing and what support he has. Find out the kind of home he lives in, the number of internal and external stairs, where the toilet and bathroom are situated, and who does the cooking, shopping and cleaning. Remember that most older people, including many of those with severe functional impairment, live in private households. Many are dependent to a greater or lesser extent upon friends and relations who contribute to their social networks, whether informally or formally. No assessment of an older person with even a slight disability is complete without a description of the people who are available to help. The informal network of support consists of both direct and extended family, and friends and neighbours (Box 6.4). This network is usually limited in size but often has a long history of contact. Although perhaps less skilled than a formal network, it has the great advantage of being flexible, familiar and continuous. The formal network consists of any basic financial entitlements, such as pensions, statutory agencies and, in the UK, the NHS, which includes a community multidisciplinary team, and the local social services, e.g. home care, meals-on-wheels and day care facilities. Local availability of these organizations will vary. Finally, voluntary organizations, religious authorities and other organizations can provide valuable help.

Activities of daily living (ADL)

An enquiry about activities of daily living (ADL) provides useful information in patients with multiple disabilities and health problems (see Table 6.2), and informs the planning of treatment and future care. In general, patients who can dress, get about outdoors, are continent, can do their own housework and cooking, and manage their own pension do not require much immediate enquiry other than about their presenting problem. Among the old and the very old, such patients are the exception. If a daily living task cannot be carried out, a detailed enquiry focusing on the reason for this must be made.

| Item | Categories |

|---|---|

| Bowels | 0 = incontinent (or needs to be given an enema) |

| 1 = occasional accident (once per week) | |

| 2 = continent | |

| Bladder | 0 = incontinent/catheterized, unable to manage |

| 1 = occasional accident (max once every 24 h) | |

| 2 = continent (for over 7 days) | |

| Grooming | 0 = needs help with personal care |

| 1 = independent face/hair/teeth/shaving (implements provided) | |

| Toilet use | 0 = dependent |

| 1 = needs some help but can do something alone | |

| 2 = independent (on and off, dressing, wiping) | |

| Feeding | 0 = unable |

| 1 = needs help cutting, spreading butter, etc. | |

| 2 = independent (food provided in reach) | |

| Transfer | 0 = unable – no sitting balance |

| 1 = major help (one or two people, physical), can sit | |

| 2 = minor help (verbal or physical) | |

| 3 = independent | |

| Mobility | 0 = immobile |

| 1 = wheelchair independent (includes corners) | |

| 2 = walks with help of one (verbal/physical) | |

| 3 = independent (may use any aid, e.g. stick) | |

| Dressing | 0 = dependent |

| 1 = needs help, does about half unaided | |

| 2 = independent, includes buttons, zips, shoes | |

| Stairs | 0 = unable |

| 1 = needs help (verbal, physical), carrying aid | |

| 2 = independent | |

| Bathing | 0 = dependent |

| 1 = independent (may use shower) |

The Barthel Index should be used as a record of what a patient does, not as a record of what he was able to do previously. The main aim is to establish the degree of independence from any help, physical or verbal, however minor and for whatever reason. The need for supervision means the patient is not independent. Performance over the preceding 24-48 hours is important, but longer periods are relevant. A patient’s performance should be established using the best available evidence. Ask the patient or carer, but also observe what the patient can do. Direct testing is not needed. Unconscious patients score 0 throughout. Middle categories imply that the patient supplies over 50% effort. Use of aids to be independent is allowed.

Drug history

Older people are prescribed more medication than any other age group. A treatment history checklist is useful when enquiring about current and past medications (Box 6.5). This is applicable to any patient with chronic illness or multiple comorbidities. Many patients do not take all (or even any) of their prescribed medications. Checking dates on bottles, and a tablet count, is a rough guide to compliance. Medicine cabinets often contain old medications kept for use in the event of future problems – patients will sometimes change a new medication for an older, trusted remedy without telling the doctor. Compliance may be improved by the use of dosette boxes, or by carers giving the patient his medications. The local pharmacist and GP will also be useful contacts when checking adherence to a treatment regimen.

Examination

Special considerations

Skin

Wrinkles are mainly due to past exposure to ultraviolet light and hence are not usually seen in covered areas. The skin of the elderly bruises easily (senile purpura); some people have skin like transparent tissue paper, described as paparaceous, especially on the backs of the hands and the forearms (Figs 6.1 and 6.2). The skin around the eyes may show yellow plaques – Dubreuilh’s elastoma. Some solar-induced changes to be aware of include keratoacanthoma, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and malignant melanoma. The most common skin lesion noted is the small red Campbell de Morgan spot, a benign lesion seen most often on the trunk and abdomen.

Leg ulcers resistant to healing are common in old age: 50% are due to venous stasis (Fig. 6.3), 10% to arterial disease and 30-40% are of mixed origin. Examination should include sensory (neuropathic ulcers) and vascular (ischaemia and varicose veins) examinations of the lower limbs. Measure the ankle and brachial blood pressures, using a Doppler meter and sphygmomanometer cuff, the Doppler meter being used instead of a stethoscope at the feet. The ankle–brachial pressure index (ABPI) is calculated using the formula:

Cardiovascular system

Heart valves, especially the aortic valve, can become less mobile, exacerbated by calcification. This is known as aortic sclerosis and is characterized by a non-radiating ejection systolic murmur, heard loudest in the aortic area. Degeneration and calcification of the mitral valve can result in either apical ejection murmurs or the more common pansystolic mitral regurgitant murmur (see Ch. 11).

Respiratory system

Kyphosis, owing to intervertebral disc degeneration and osteoporosis, and calcification of the costal cartilages make the chest wall more rigid and less expansible. A reduction in pulmonary elasticity with age may be responsible for some hyperinflation on a chest radiograph, but this is principally due to pathological hyperexpansion associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Generally, the physical signs of respiratory system disease are the same in the old as in the younger patient. Measurements of peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) and vital capacity (VC) are reduced (see Table 6.1) but, despite these changes, normal oxygenation is maintained and the normal adult ranges for oxygen saturation should be used.

Gastrointestinal system

Abdominal examination may be limited by patients’ orthopnoea, kyphoscoliosis or other disabilities. However, always try to perform an appropriate assessment. If abdominal examination is limited by such disabilities, the patient will also find it difficult to lie supine for investigations such as computed tomography (CT) scanning or colonoscopy. The indications for digital rectal examination are the same as for younger patients, but this may not be feasible or appropriate, particularly in the very disabled or frail older patient. Constipation severe enough to cause faecal impaction is not uncommon and can have serious consequences (Box 6.6). This is often iatrogenic, but if of recent onset should be investigated appropriately.

Nervous system

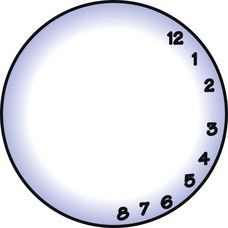

Central nervous system examination should routinely include an assessment of higher cortical function (language, perception and memory). If cognitive impairment is suspected, assess the mental state early in the interview before the patient tires and record the result in the clinical notes (see below). As well as the Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (see below), use the ‘clock test’. The patient is presented with a drawn circle, about 10-15 cm in diameter, and asked to fill in the numbers of a clock face (Fig. 6.4). Abnormalities may be due to visual impairment, agnosia (owing to right parietal lobe lesions) or cognitive impairment. This test is easily reproducible and less influenced by cultural and language problems than the AMTS or MMSE. A newer test, the Test Your Memory (TYM), has recently been introduced for patients attending diagnostic memory clinics or outpatient clinics, to fill in prior to be seen by medical staff.

Dysphasia, i.e. difficulty in encoding and decoding language, is usually associated with a left hemisphere lesion (see Ch. 14). Dyspraxia is difficulty initiating and carrying out voluntary movements, for example of the tongue, and hence can affect speech. Dysarthria has many causes, including local factors in the mouth and dentition, stroke, Parkinson’s disease and other neurological disorders. Dysphonia, an abnormality of the quality of the voice (e.g. hoarseness), can be due to anxiety, vocal abuse, local disease of the larynx and pharynx or hypothyroidism. It is common after surgery to the throat and intubation. Dysfluency (stammer) is found in people of all ages.

It is essential to observe the walking or gait pattern wherever possible. This may reveal subtle evidence of hemiparesis, poor balance (Box 6.7) or the furniture-clutching gait of the patient with longstanding mobility problems. When observing the gait, always have someone walk alongside the patient to offer a helping hand in case he stumbles or falls. Occasionally patients claim that they are capable of carrying out activities when in reality they cannot. Always check the feet for chiropody problems (e.g. onychogryphosis), which cause a ‘painful’ or antalgic gait.

Vision and the eyes

Visual acuity should be assessed and any loss of vision noted, together with the history of development of the visual disorder. Acute and chronic causes of loss of vision should be considered during the examination (Box 6.8). If the patient wears glasses, ask to see them. A state of disrepair may be an indication of cognitive impairment and/or their underuse, thereby explaining falls and misinterpretation of the environment. The visual fields should always be assessed. It is common to see irregular, asymetrical pupils due to previous iridotomy. Pupillary responses are normal in the well, older patient, but stroke and medication may cause abnormal size and responses. Abnormalities such as Horner’s syndrome and palsies of the third, fourth and sixth cranial nerves are relatively common in the elderly, related to stroke and neoplastic disease. Funduscopy should be attempted wherever necessary, but may be difficult when there are cataracts.

The ‘geriatric giants’

Professor Bernard Isaacs drew attention to the four ‘geriatric giants’ (see Box 6.1) – immobility, instability (falls), incontinence and intellectual impairment – in the mid 1970s. Impaired senses (vision, hearing, speech and language), iatrogenesis and pressure ulcers are now commonly included. These are important causes of disability and illness, but are not diagnoses in themselves so much as presentations of disease. In any older person presenting with one of the geriatric giants, the underlying causes must be considered.

Immobility

Within the bounds of common sense, the patient should be asked or helped to stand up and attempt a few steps, during which the gait can also be assessed (see above). Always have someone in close attendance in case of falls. The patient may be able to mobilize but unable to get out of a chair or bed unaided. Look for signs of distress on standing that may not have been mentioned by the patient. Tentative steps or clutching helpers may indicate loss of confidence or apraxia. Sometimes a diagnostic gait pattern is found (Box 6.9).

Box 6.9 Abnormalities of gait

The broad-based, unsteady gait of cerebellar ataxia

The broad-based, unsteady gait of cerebellar ataxia

The high-stepping, foot-slapping unsteady gait of sensory ataxia

The high-stepping, foot-slapping unsteady gait of sensory ataxia

The apraxic gait, with rapid small steps like a slipping clutch, or with feet apparently glued to the floor

The apraxic gait, with rapid small steps like a slipping clutch, or with feet apparently glued to the floor

The parkinsonian gait, with loss of postural reflexes, festination, a fixed posture, tremor, rigidity, hypokinesia of face and limbs, excess salivation and seborrhoea

The parkinsonian gait, with loss of postural reflexes, festination, a fixed posture, tremor, rigidity, hypokinesia of face and limbs, excess salivation and seborrhoea

The gait of stroke with dragging of one leg

The gait of stroke with dragging of one leg

The myopathic waddling gait due to weak proximal muscles, e.g. from osteomalacia

The myopathic waddling gait due to weak proximal muscles, e.g. from osteomalacia

The tentative antalgic or painful gait of patients with acute pain from, e.g., arthritis, injury or ulceration

The tentative antalgic or painful gait of patients with acute pain from, e.g., arthritis, injury or ulceration

Instability/falls

It is said that ‘young people trip, but old people fall’. With age, muscle strength is lost and postural reflexes become impaired. Falls are therefore common in old age, especially in the very old. Several causes may coexist (see Box 6.7). Even a single fall should lead to a detailed history and examination, and a corroborative history sought from spouse or friends. In a patient who was previously well, a search should be made for new acute illness. If none is present, the fall may be deemed ‘accidental’ due to environmental or mechanical factors, although this is a diagnosis of exclusion. Information about the pattern of any previous falls can be helpful: frequency, relationship to posture, activity or time of day, prewarning and residual symptoms following the fall, and any avoiding steps taken by the patient should be ascertained. The absence of any warning implies a sudden event, usually neurological or cardiovascular in nature. Sinister symptoms associated with falling include loss of consciousness (although, notoriously, this is poorly reported), focal neurological deficit, features of seizure, chest pain, palpitations or other cardiorespiratory symptoms. The most useful clinical investigation in older fallers is to watch them walking. Patients may also require 24-hour ambulatory electrocardiograph monitoring, a CT head scan and sometimes tilt-table testing.

Incontinence

When taking a history of urinary of faecal incontinence, try to differentiate between loss of ability to control voiding and failure to identify or reach an acceptable place. Find out how socially disabling the incontinence has become: many patients become isolated or afraid to go out because of the associated anxiety and potential embarrassment. Clinical examination should include rectal and vaginal examinations, assessment of the prostate gland, evaluation of the pelvic floor muscles and culture of a mid-stream specimen of urine. An incontinence chart kept for a few days may suggest a recognizable pattern of urinary and/or faecal incontinence. The specialist help of a continence adviser is often useful. Causes of urinary incontinence are shown in Box 6.10.

Pressure ulcers

The mean capillary pressure in the skin of healthy young adults is approximately 25 mmHg. A bedridden patient or a person lying on the floor generates pressures in the skin in excess of 100 mmHg, especially over the sacrum, heels and greater trochanters (96% of ‘decubitus’ pressure ulcers occur below the level of the waist). Such pressures lead to occlusion of cutaneous blood vessels, causing the surrounding tissues, including the skin, to become hypoxic. In such circumstances, necrosis of the skin, adipose tissue and muscle may develop in as little as 4 hours. About 80% of pressure ulcers are superficial (Fig. 6.5). They occur mainly in dehydrated, immobile and incontinent patients exposed to sustained pressure. People with impaired sensation, or with diabetes, are especially vulnerable. Decubitus ulcers are always potentially preventable, but will occur in any setting if skin care is disregarded. Any superficial ulcer will deepen if the pressure is not relieved. Deep ulcers (Fig. 6.6) are formed when localized high pressure applied to the skin cuts off a wedge-shaped area of tissue, usually adjacent to a bony prominence.

All at-risk patients should have active skin care management, including good nursing care and adequate hydration, started immediately a new illness or injury occurs, whether at home or in hospital. All pressure area sites must be inspected at the first clinical assessment, and again at regular intervals during the illness. An alternating-pressure air mattress (APAM), in which horizontal air cells (Fig. 6.7) inflate and deflate over a short cycle, constantly supporting the patient, provides periods of low pressure at all pressure sites, and good protection.

Confusion

The confused older patient

‘Patient confused, no history available’ is a phrase that should never be used. It is crucial to establish whether the patient is orientated in place, time and person, and whether they are alert. A corroborative history from a friend or relative, and thorough clinical examination, will help decide whether the confusional state is acute or chronic. It is important to use a standard test of mental function (Box 6.11). Explain to the patient that you wish to test his memory. With experience, it is possible to check most of the items in the mental test score by working them into your introductory conversation. Hearing and speech impairments (such as nominal dysphasia) can make people appear very cognitively impaired, but should be easy to recognize. Depressed patients tend to perform poorly on mental test scores. If a problem is detected with a simple test, proceed to a more in-depth assessment using the MMSE (see Ch. 7). Assessment of mental state is most valuable when applied serially over a period of time.

Assessment of capacity

Legally, competent adults (relatives or carers) are not able to make any decisions about the medical management or social care of another adult, unless they have been made their legal representative through lasting powers of attorney (LPAs) or being a court of protection-appointed deputy. Similarly, cognitively impaired patients may be unable to make a valid and consistent decision. Such patients require assessment of their mental capacity when making important decisions about their health or social care. A person lacks capacity if they are deemed to have a temporary or permanent impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, their mind or brain. The Mental Capacity Act (2005) (see the Department of Health Web site for more information: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Bulletins/theweek/Chiefexecutivebulletin/DH_4108436) defines a person as lacking capacity (i.e. someone who is unable to make a valid decision) if they are unable to: