Disorders of the hand and fingers

Disorders of the inert structures

The capsular pattern

• How did it all start? The possibilities are: no apparent cause, trauma or post-immobilization. A spontaneous onset indicates the possibility of rheumatoid arthritis or of a simple arthrosis. Trauma suggests traumatic arthritis.

• Are other joints affected as well? If they are, this suggests a rheumatoid condition.

• Which joints were affected first, the distal or the proximal joints? Arthrosis usually starts at the distal interphalangeal joints, whereas rheumatoid arthritis tends to start at the metacarpophalangeal joints.

• Is the joint capsule swollen? Swelling often occurs in a rheumatoid or traumatic arthritis.

• Does the joint change colour? The joint becomes red in gout.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is undoubtedly the most deforming and most incapacitating disorder of the hand.1

As in any other patient, symptoms may develop that have nothing to do with the patient’s rheumatoid arthritis. Trigger finger, carpal tunnel syndrome and de Quervain’s disease are common, and another possibility is a ganglion lying between the heads of the second and third metacarpal bones, which gives rise to vague local aching and responds well to aspiration.2

Traumatic arthritis

Traumatic arthritis of the finger joints does not respond satisfactorily to any treatment. Intra-articular injection with a steroid, so useful in traumatic arthritis in the toe joints, affords no corresponding benefit in the fingers. Recovery is spontaneous over 6–18 months, depending on the severity of the original trauma and the age of the patient. Sometimes manual therapeutic techniques may favourably alter the natural course.3 Immobilization is strongly contraindicated.

Arthrosis

Occasionally arthrosis in one joint develops as the result of severe injury but more often the condition has a spontaneous onset and affects several joints. Women between 40 and 60 years of age are often affected, and there is a strong familial predisposition.4

Arthrosis begins at the distal interphalangeal joints, and its knobbly appearance is quite different from rheumatoid arthritis. Both hands are usually affected more or less symmetrically. The index, middle and ring fingers are most usually affected. At the base of the distal phalanx, two small rounded bosses on the dorsum of the joint (Heberden’s nodes)5 can be seen. A varus deformity may develop at a distal joint, usually at the index. Some years later, the arthrosis may spread to the proximal interphalangeal joints (with the formation of nodes at index and middle fingers – Bouchard’s nodes); it seldom reaches the metacarpophalangeal joints. From time to time, a new node forms at an affected joint and the patient will mention some aching or slight pain over 1 or 2 months, during which time the fingertip may occasionally become pink. The colour is mottled and different from the shiny red of gout. After a month or two the discolouration passes off and the node ceases to be painful.

The radiograph clearly shows the usual arthrotic changes – osteophytes and erosion of cartilage.

Disorders of the contractile structures

Strains of muscles and tendons in the hand are not infrequent. They have no tendency to spontaneous cure. Diagnosis is not difficult and conservative treatment leads to good results. All the intrinsic muscles of the hand and their short tendons respond immediately to adequate deep transverse friction but not to infiltrations with steroids. In contrast, friction has no effect on the long flexor tendons in the palm but triamcinolone infiltration is successful.7

Dorsal interosseous muscles

Pain

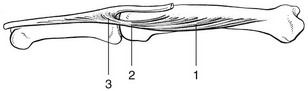

There are three possible localizations for the lesion: in the muscle belly; in the tendon where it crosses the metacarpophalangeal joint; and at the insertion into the base of the phalanx (Fig. 1).

Technique: friction to the muscle belly![]()

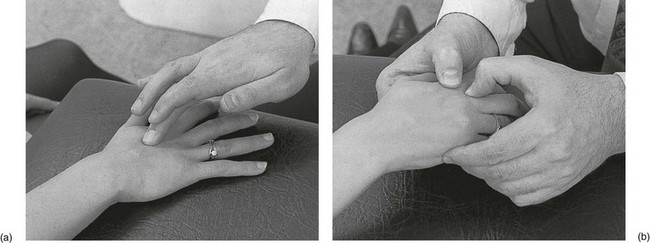

The patient sits at the couch with the hand resting on it. The therapist sits opposite the patient. The tender spot between the shafts of the metacarpal bones is palpated for, keeping the finger as parallel as possible to the metacarpals. Friction is imparted with the middle finger, reinforced by the index finger (Fig. 2a). The movement is pure pronation–supination, transverse to the muscular fibres.

Technique: friction to the tendon![]()

It is sometimes difficult to get the finger to the exact spot because it lies more or less between the knuckles. Therefore the following procedure is used. With one hand the therapist takes the patient’s hand, with the fingers in the palm of the patient’s hand. The tips of the middle and ring fingers lie on the palmar aspect of the knuckle that contains the lesion and push the bone upwards. At the same time the thumb is laid on the dorsal aspect of the adjacent knuckle, which is pushed downwards. This manūuvre brings the affected tendon within reach of the thumb of the other hand. With the fingers of this hand counterpressure is exerted (Fig. 2b). The friction is given with the thumb, starting at the palmar aspect of the tendon and ending at the dorsal side of it. The movement is achieved by a supination movement of the forearm.

Thenar muscles

Treatment consists of a few sessions of deep transverse friction.

Trigger finger

Trigger finger is a common condition causing pain and disability in the hand. It can arise spontaneously or can be the result of repetitive minor trauma or a complication of rheumatoid arthritis. Primary trigger finger occurs most commonly in the middle fifth to sixth decades of life and up to six times more frequently in women than men.9 The third or fourth finger is most commonly involved. The disorder is caused by swelling of one of the digital flexor tendons just proximal to the metacarpophalangeal joint, in combination with narrowing of its tendon sheath.

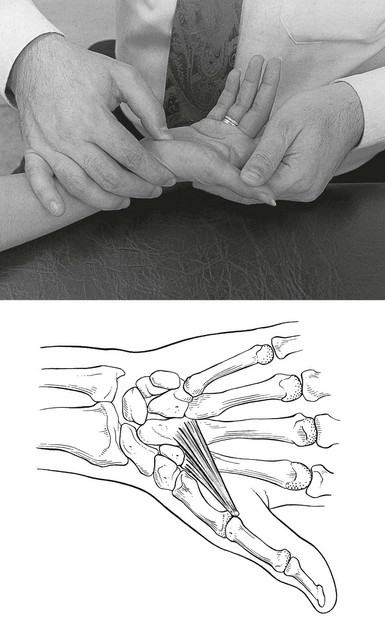

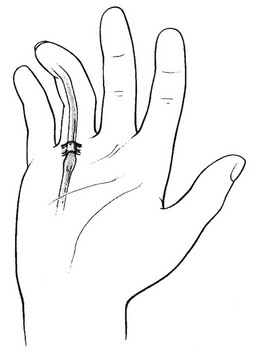

The condition presents with discomfort in the palm during movement of the involved digits. Gradually the flexor tendon causes painful popping or snapping as the patient flexes and extends the digit. As the condition progresses, the digit may begin to lock in a particular position, more often flexion, which may require gentle passive manipulation into full extension. A snap accompanies disengagement. Trigger finger arises through a discrepancy in the diameter of the flexor tendon and its sheath at the level of the metacarpal head known as the A1 pulley. This thickening of the sheath can result in a narrowed tunnel for tendon excursion and ultimately result in a block to tendon excursion.10 However, the flexors are usually powerful enough to overcome this obstruction, whereas the weaker extensors are less able to counteract the block, resulting in the finger being locked in flexion. A painful nodule, the result of intratendinous swelling, is easily palpated in the palm, just proximal to the head of the metacarpal bone (Fig. 4).

Fig 4 Trigger finger.

If the condition gives rise to painful symptoms, infiltration with 10 mg of triamcinolone acetonide in and around the flexor sheath at the level of the A1 pulley should be given.11,12 Steroid injection is an effective method of treating patients with trigger finger and should be considered as the preferred treatment.13–16 If the result is not adequate, the tendon sheath can be slit up either at open surgery or percutaneously.17 Success rates have been reported as over 90%; however, its use is tempered by the risk of digital nerve or artery injury and tendon bowstringing.18,19

Tendon rupture

Mallet finger

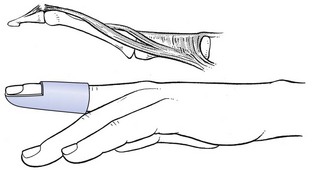

As the result of an injury that flexes the distal interphalangeal joint while it is actively held in extension, the long extensor tendon may rupture (Fig. 6) or may become detached (avulsion fracture) from the distal phalanx. Distinction between the two can be made by radiography.

Mallet injuries with and without a bony fragment may be effectively treated by splinting the distal interphalangeal joint in extension for 8 weeks, followed by 1 month of night splinting.20 Dorsal, volar, or pre-fabricated stack type splints all can be used but care must be taken to avoid dorsal skin ischemia.21 When a bone fragment has been retained with the extensor tendon, the opportunity to heal is enhanced because of the greater healing potential of bone compared to tendon.22 The proximal interphalangeal joint should be left free, as immobilization of the proximal interphalangeal joint and its resultant stiffness may cause more morbidity than the original injury. Patients are counseled to expect a slight extensor lag (5–10°) under the best circumstances, with a mild loss of total motion.23 Internal fixation of mallet fingers is recommended in cases of volar subluxation of the distal phalanx or in cases where the dorsal component is greater than one-third of the joint surface.24

Dupuytren’s contracture

This disorder, named after G. Dupuytren,25 is a painless contracture of the palmar aponeurosis. The aetiology is still unknown but it seems to occur more often in combination with alcoholism, disorders of the liver, diabetes and epilepsy.26–28 It is common in men after the age of 30, whereas in women it does not occur under the age of 45.29 A small node in the palm of the hand is the initial symptom. Further contraction of the palmar fascia leads to flexion contracture of the fingers, especially the ring and little fingers, which are affected in 85%.30

Südeck’s atrophy

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome (RSDS), or Südeck’s atrophy, is a curious disorder that is not uncommon. Different terminology has been used to label the same condition: Südeck’s atrophy, causalgia, algodystrophy, algoneurodystrophy, reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome (RSDS).31 It is a controversial condition. The controversy concerns the manner in which the sympathetic nervous system is involved in RSDS. It was redefined in 1996 by an ad hoc International Association for the Study of Pain task force that suggested changing the name to ‘complex regional pain syndrome’ (CRPS).32–34 CRPS type 1 is reflex sympathetic dystrophy; type II is causalgia.35

It occurs most commonly as a complication of major or minor trauma (up to 5% of patients with traumatic injuries) or in patients with myocardial ischaemia (5–20%) or hemiplegia (12–20%).36 Kozin37 stated that RSDS was found to occur most frequently after fracture (25%) or other trauma (27%). In 27% of cases, no specific precipitating event could be identified. Central nervous system or spinal disorders, myocardial ischaemia and peripheral nerve injury are responsible for, respectively, 12, 6 and 4% of cases.

The main symptom is post-traumatic pain which is disproportionate to the injury. It spreads beyond the distribution of any single peripheral nerve, is usually felt distally in the arm and is often described as ‘burning’.38 Tenderness is always present and is occasionally associated with allodynia and enhanced sensitivity to palpation. Swelling of the affected part is often present and pitting or non-pitting oedema may be found. Dystrophic skin changes are seen: nail and hair changes (hypertrichosis), shiny and taut skin and loss of wrinkling.

The radiographic changes (patchy osteoporosis) have been well described by Südeck,39 Kienböck40 and Hermann et al.41 A bone scan may be useful to arrive at a diagnosis.

The treatment of complex regional pain syndrome type I (CRPS-I) is subject to much debate. There is more or less concensus about the following.42 For pain treatment, the WHO analgesic ladder is advised with the exception of strong opioids. For neuropathic pain, anticonvulsants and tricyclic antidepressants may be considered. For inflammatory symptoms, free-radical scavengers (dimethylsulphoxide or acetylcysteine) are advised. To promote peripheral blood flow, vasodilatory medication may be considered. Percutaneous sympathetic blockades may be used to increase blood flow in case vasodilatory medication has insufficient effect.43,44 To decrease functional limitations, standardised physiotherapy and occupational therapy are advised.45

References

1. Tubiana, R, Ghozlan, R, Minkes, CJ. Main rhumatoïde, Appareil Locomoteur. Encyclopédie Médicochirurgicale. 1978; 10:14067.

2. Rhoades, CE, Gelberman, RH, Manjarris, JF, Stenosing tenosynovitis of the fingers and thumb. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1984; 190:236. ![]()

3. Mink, AJF, ter Veer, HJ, Vorselaars, JACTH. Extremiteiten, Functie-onderzoek en Manuele Therapie, 6th ed. Utrecht: Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema; 1990.

4. Veys, EM, Mielants, H, Verbruggen, G. Reumatologie. Ghent: Omega Editions; 1985.

5. Heberden, W. Commentaries on the History and Cure of Diseases. London: Payne; 1802.

6. Dieppe, PA, Calvent, P. Crystals and Joint Disease. London: Chapman & Hall; 1982.

7. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol I, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

8. Haloua, JP, Collin, JP, Coudeyre, L, Paralysis of the ulnar nerve in cyclists. Ann Chir Main 1987; 6:282. ![]()

9. Weilby, A, Trigger finger. Incidence in children and adults and the possibility of a predisposition in certain age groups. Acta Orthop Scand 1970; 41:419–427. ![]()

10. Sampson, SP, Badalamente, MA, Hurst, LC, Seidman, J, Pathobiology of the human A1 pulley in trigger finger. J Hand Surg (Am). 1991;16(4):714–721. ![]()

11. Taras, JS, Raphael, JS, Pan, WT, et al, Corticosteroid injections for trigger digits: is intrasheath injection necessary? J Hand Surg [Am] 1998; 23:717–722. ![]()

12. Kazuki, K, Egi, T, Okada, M, et al, Clinical outcome of extrasynovial steroid injection for trigger finger. Hand Surg 2006; 11:1–4. ![]()

13. Lambert, MA, Morton, RJ, Sloan, JP, Controlled study of the use of local steroid injection in the treatment of trigger finger and thumb. J Hand Surg. 1992;17B(1):69–70. ![]()

14. Buch-Jaeger, N, Foucher, G, Ehrler, S, Sammut, D, The results of conservative management of trigger finger. A series of 169 patients. Ann Chir Main Memb Super. 1992;11(3):189–193. ![]()

15. Akhtar, S, Burke, FD, Study to outline the efficacy and illustrate techniques for steroid injection for trigger finger and thumb. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(973):763–766. ![]()

16. Peters-Veluthamaningal, C, van der Windt, DA, Winters, JC, Meyboom-de Jong, B, Corticosteroid injection for trigger finger in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1). ![]()

17. Eastwood, DM, Gupta, KJ, Johnson, DP, Percutaneous release of the trigger finger: an office procedure. J Hand Surg. 1992;17A(1):114–117. ![]()

18. Pope, DF, Wolfe, SW, Safety and efficacy of percutaneous trigger finger release. J Hand Surg [Am] 1995; 20:280–283. ![]()

19. Park, MJ, Oh, I, Ha, KI, A1 pulley release of locked trigger digit by percutaneous technique. J Hand Surg [Br] 2004; 29:502–505. ![]()

20. Wehbé, MA, Schneider, LH, Mallet fractures. J Bone Joint Surg 1984; 66A:658. ![]()

21. Kalainov, DM, Hoepfner, PE, Hartigan, BJ, et al, Nonsurgical treatment of closed mallet finger fractures. J Hand Surg [Am] 2005; 30:580–586. ![]()

22. Hooyboer, PGA, Vuursteen, PJ. De behandeling van de mallet finger; stack-spalk of tenodermodese. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1990; 4:134.

23. Patel, MR, Desai, SS, Bassini-Lipson, L, Conservative management of chronic mallet finger. J Hand Surg [Am] 1986; 11:570–573. ![]()

24. Badia, A, Riano, F, A simple fixation method for unstable bony mallet finger. J Hand Surg [Am] 2004; 29:1051–1055. ![]()

25. Dupuytren, G. Leçons Orales de Clinique Chirurgicale. Paris: Baillière; 1832.

26. Hueson, JT. Dupuytren’s contracture. In: Flynn JE, ed. Hand Surgery. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1982:797.

27. Lamb, DW. Dupuytren’s disease. In: Lamb DW, Kuczynski K, eds. The Practice of Hand Surgery. Oxford: Blackwell; 1981:470.

28. James, JIP. The genetic pattern of Dupuytren’s disease and idiopathic epilepsy. In: Hueston JT, Tubiana R, eds. Dupuytren’s Disease. 2nd English ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1985:94.

29. Ewing, J. Neoplastic diseases. In: Rothman R, Simeone F, eds. A Treatise on Tumors. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1982:368.

30. Lukes, RJ, Collins, RD, New approaches to the classification of lymphomata. Br J Cancer 1975; 31:1. ![]()

31. Alvarez-Lario, B, Aretxabala-Alcibar, I, Alegre-Lopez, J, Alonso-Valdivielso, JL, Acceptance of the different denominations for reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(1):77–79. ![]()

32. Marchettini, P, Lacerenza, M, Formaglio, F, Sympathetically maintained pain. Current Rev Pain. 2000;4(2):99–104. ![]()

33. Stanton-Hicks, M, Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: a sympathetically mediated pain syndrome or not? Current Rev Pain. 2000;4(4):268–275. ![]()

34. Stanton-Hicks, M, Complex regional pain syndrome (type I, RSD; type II, causalgia): controversies. Clin J Pain. 2000;16(2 Suppl):S33–S40. ![]()

35. Viel, E, Ripart, J, Pelissier, J, Eledjam, JJ, Management of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Ann Méd Interne (Paris). 1999;150(3):205–210. ![]()

36. Davis, SW, Shoulder–hand syndrome in a hemiplegic population: 5 year retrospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1977; 58:3553. ![]()

37. Kozin, F. The painful shoulder and reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. In: McCarty DJ, ed. Arthritis and Allied Conditions. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1985:1322.

38. Goldstein, DS, Tack, C, Li, ST, Sympathetic innervation and function in reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2000;48(1):49–59. ![]()

39. Südeck, P. Über die akute entzündliche Knochenatrophie. Arch Klin Chir. 1900; 62:147.

40. Kienböck, R. Über akute Knochenatrophie bei Entzündungsprocessen an den Extremitäten (falschlich sogenannte Inaktivitätsatrophie der Knochen) und ihre Diagnose nach dem Röntgenbild. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1901; 5:1345.

41. Hermann, LG, Reinecke, HG, Caldwell, JA. Posttraumatic painful osteoporosis: a clinical and roentgenological entity. Am J Roentgenol. 1942; 47:353.

42. Perez, RS, Zollinger, PE, Dijkstra, PU, et al, CRPS I task force. Evidence based guidelines for complex regional pain syndrome type 1. BMC Neurol 2010; 10:20. ![]()

43. Kozin, F, Reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. Bull Rheum Dis. 1986;36(3):632–638. ![]()

44. Bushnell, TG, Cobo-Castro, T, Complex regional pain syndrome: becoming more or less complex? Manual Therapy. 1999;4(4):221–228. ![]()

45. Oerlemans, HM, Oostendorp, RA, de Boo, T, et al, Adjuvant physical therapy versus occupational therapy in patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy/complex regional pain syndrome type I. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(1):49–56. ![]()