Disorders of the forefoot and toes

The forefoot

Short first metatarsal bone

This is known as Morton’s syndrome. Sometimes a short first metatarsal is related to pain, sometimes it is not. If the first metatarsal is too short and hypermobile, most of the body weight will be borne by the second metatarsal. Because of the hypermobility and shortening, the transverse arch becomes depressed and metatarsalgia results (p. e308 of this chapter).

March fractures

This condition was first described in 1855 by Breithaupt,1 a Prussian military doctor, who stated that many soldiers developed painful swellings at the dorsum of their feet after long marches. He called this Schwellfuss but the cause remained unclear until Stechow2 proved that the condition is caused by stress fracture.

Stress fractures of the metatarsal bones comprise 3.7% of all sport-related injuries, with the second and third metatarsal accounting for 80–90% of the fractures.3–5 Stress fractures of the metatarsals are also common in military recruits and in long-distance runners. It has been reported that up to 20% of stress fractures in athletes6 and 23% of stress fractures in military recruits7 are located in the metatarsals.

The lesion should be suspected when a patient presents with unilateral and localized warmth and oedema at the dorsum of the foot. Often the symptoms appear after a long walk but sometimes there is no specific precipitating activity. It is surprising that children are almost as liable to marching fractures as adults. Cyriax’s8 (his p. 440) youngest patient was a 6-year-old boy.

During the first few days, the fracture (usually a hair-line crack) may not be revealed by routine radiography. The diagnosis is confirmed after a few weeks, when the callus formation around the fracture becomes radiologically apparent. Earlier confirmation of the diagnosis is obtainable by either radionuclide bone imaging,9,10 or ultrasound examination.11–13

Differential diagnosis

Localized swelling, warmth and tenderness in the forefoot can also occur in:

• Gout in one of the tarsometatarsal joints. A history of recurrent acute attacks of arthritis at the same joint or in other joints is helpful.

• Rheumatic forms of arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and reactive arthritis. These disorders affect multiple joints. The history is also longer than the usual 6 weeks of that of a march fracture.

• Freiberg’s arthritis at the second metatarsophalangeal joint. Although ischaemic epiphyseal necrosis of the base of the second metatarsal bone occurs in adolescence, the disease may be asymptomatic until adult life, when the deformity of the joint and the degenerative arthritis produce pain.

• Ringworm and erysipelas. Local cellulitis, caused by an infection of β-haemolytic Streptococci spp. or fungi, can cause considerable redness, thickening and tenderness. In erisypelas, there is malaise, chills and fever, together with an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate. In ringworm, there is considerable itching and inspection of the interdigital clefts very often reveals a small localized infection between two toes.

Treatment

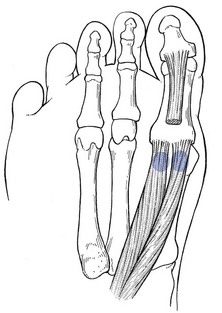

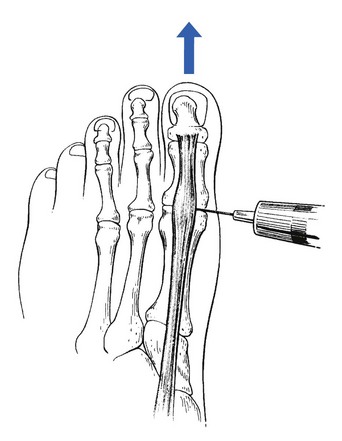

The patient lies supine on the couch. The therapist sits facing the foot and with the ipsilateral hand encircles the toes in such a way that the thumb lies at the dorsal aspect and the proximal interphalangeal joint of the flexed index finger presses under the metatarsophalangeal joints. The big toe is left free. The thumb keeps the toes flexed and the index finger presses upwards, so as to render the metatarsus convex. The shafts move apart and the muscle bellies lie closer to the surface. The middle finger of the other hand, reinforced by the index finger, is now placed in the groove between the two metacarpal bones (Fig. 1). Fingers, wrist and forearm are kept in one line and parallel to the metatarsal bones. Deep friction is imparted by rotating the fingers through an alternate pronation and supination movement of the forearm, so that the muscle is moved between the fingertip and the metatarsal shaft.

Fractures of the fifth metatarsal

Tuberosity avulsion fractures are the most common and usually complicate an inversion sprain (see p. 776). The majority heal with symptomatic care in a hard-soled shoe.

The true Jones fracture is defined as an acute fracture at the junction between the proximal diaphysis and metaphysis of the fifth metatarsal without distal extension beyond the fourth to fifth intermetatarsal articulation.14 The mechanism of injury is believed to be an abduction force applied to the forefoot with simultaneous ankle plantar flexion.15 A Jones fracture can be treated with 6 to 8 weeks of non-weight-bearing immobilization resulting in fair to good outcomes.16,17 Operative treatment is selected if the patient is a high-performance athlete or nonoperative treatment fails.18

A proximal diaphyseal fifth metatarsal stress fracture is defined as a stress fracture in the zone of the proximal fifth metatarsal immediately distal to the Jones fracture’s anatomic area.19 The mechanism of this injury is believed to be a repetitive load applied under the metatarsal head over a relatively short time, resulting in an overuse phenomenon. A proximal diaphyseal fifth metatarsal fracture may have a very long healing time and non-union can develop in as much as 25% of cases. For this reason, operative treatment is usually recommended.20

Splay foot

Treatment includes a high heel with a horizontal upper surface, which prevents the forwards gliding of the talus and thus releases the forefoot (see Ch. 59), and energetic training of the short plantiflexor muscles of the toes.

Localized splaying indicates a ganglion lying between two metatarsal heads. When the patient stands, an excessive interval is seen between two toes and palpation reveals a semisolid tumour keeping the heads apart (see p. e309 of this chapter).

The first metatarsophalangeal joint

The capsule of the first metatarsophalangeal joint is reinforced on the plantar surface by a fibrocartilaginous plate that is attached distally to the proximal phalanx and proximally to the plantar aspect of the neck of the first metatarsal. This volar plate contains the two sesamoid bones, inserted in the tendons of the flexor hallucis brevis (Fig. 2). The flexion–extension movement is a rolling and sliding of the metatarsal head within the stable support made up of the base of the proximal phalanx and the volar plate.21

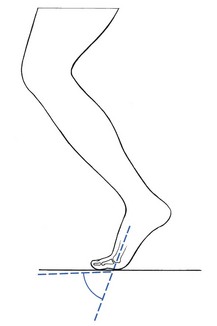

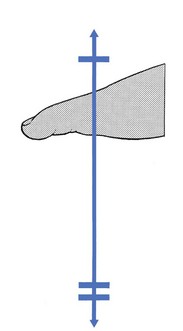

The joint is extremely important for normal gait. There must be 60–70% of extension with the first metatarsal to allow the hallux to function normally during the stance phase of gait.22 In the final stage of forefoot contact, 40% of body weight is imposed on the joint and the big toe23 (Fig. 3).

During extension, the sesamoids are drawn from the head–neck junction of the first metatarsal to the distal head area. The average range of motion is 50°.24 Apart from their function in weight bearing, the sesamoids also serve as a fulcrum that increases the mechanical advantage of the flexor hallucis brevis tendon.

The clinical examination of the big toe is summarized in Box 1.

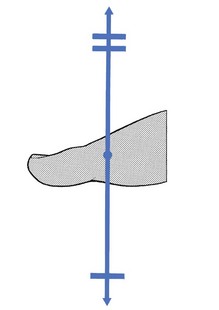

The capsular pattern

The capsular pattern at the first metatarsophalangeal joint is slight limitation of flexion, together with marked limitation of extension (Fig. 4).

Gout

The first metatarsophalangeal joint is usually the first joint to be affected in gout. The attack is characterized by a sudden onset of intense pain, frequently at night. The joint is swollen and exquisitely tender. The overlying skin is tense, warm and dusky red. The attack lasts 1–2 weeks, and asymptomatic periods of months or years commonly follow the initial acute attack.25

An acute attack can frequently be aborted by colchicine or by one of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.26–28 When attacks are frequent or other gouty complications such as tophi occur, lowering of blood uric acid is indicated.29

Arthritis in adolescence

Early osteoarthrosis at the first metatarsophalangeal joint, mostly bilateral, occurs in adolescence and is the result of osteochondritis dissecans.30 It leads to the formation of a hallux rigidus in young adults.

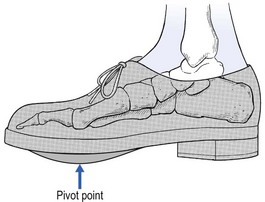

Because the patient is unable to extend the big toe during the foot-off phase, treatment must aim to introduce a forefoot movement that does not interfere with the mobility of the joint but nevertheless enables the heel to move upwards while the forefoot is on the ground. To do this, a ‘rocker’ is placed in or under a thick and solid sole of a shoe, at the joint line (Fig. 5).

Instead of extending at the first metatarsophalangeal joint, the forefoot will now rock during a normal gait. If this is not adequate, a steel plate in the sole prevents further stress on the rigid joint, but the resulting gait is less natural.31

Surgery for hallux rigidus consists of resection of osteophytes and metatarsal head (cheilectomy)32 or resection arthroplasty.33–35

Traumatic arthritis

This results from a direct trauma or forceful hyperextension of the joint. This is the case in osteoarthrosis, in which a superimposed post-traumatic arthritis easily occurs. It is also encountered in certain sports, such as soccer and American football.36–39 Treatment consists of an intra-articular injection of 10 mg of triamcinolone and prevention of further overstretching.

Arthrosis in middle age

Osteoarthrosis at the first metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ) is the second most common disorder affecting the foot after hallux valgus. The prevalence of the condition increases with age, and it has been reported that radiographic changes in the first MPJ are evident in approximately 46% of women and 32% of men at 60 years of age.40 The degeneration and stiffness is not the result of a previous aseptic necrosis but has probably been induced by trauma or repetitive stresses. Sometimes a heavy weight falling on the joint or a fracture is the precipitating cause. Repetitive stresses during extension (as in women wearing high heels) can influence the degeneration.

Deterioration is slow and insidious, and therefore symptoms may not arise for years. They appear only when the joint becomes overstrained.41 In other words, the source of the pain is not the osteoarthrosis as such but the superimposed post-traumatic arthritis. Symptoms therefore start when some dorsiflexion is lost: in men when 45° of extension range has been lost, in women who wear high heels when only 20 or 30° has been lost. The typical case is consequently a middle-aged man or woman who has pain at the big toe during and after walking.

Clinical examination shows a painful and markedly limited extension of the big toe, together with slight limitation of flexion. The end-feel is hard. Osteophyte formation and some local tenderness can be palpated at the dorsum of the joint.42

Because the pain is the result of a post-traumatic arthritis, it can be abolished by one intra-articular injection of triamcinolone. If the patient is careful in the future, wears appropriate shoes with thick, solid soles and avoids high heels, relapses are not to be expected. During the last decade an alternative treatment termed ‘viscosupplementation’ – the intra-articular injection of hyaluronan with the aim of restoring the viscoelasticity of the synovial fluid – has been proposed and studies show promising results.43,44 Good results can also be achieved by traction. Alternatively, mobilization, using traction–translation techniques can be used.45 In advanced cases, in which there is hallux rigidus, the use of a ‘rocker’ and a steel sole must be advised (Fig. 5). If all conservative treatment fails, surgery can be undertaken.46,47

The patient sits with the foot flat on the couch. The physician grasps the distal phalanx and pulls it in an axial direction, with a slight flexion component. This distracts the joint surfaces and enables the joint line to be identified, which is not always easy to do in patients with large osteophytes: the depression between the osteophyte and the bone should not be mistaken for the joint line. A 1 ml syringe is filled with steroid suspension and fitted with a thin 2 cm needle. After identifying the joint line and the tendon of the long extensor, the needle is passed into the space between the two bones, medially to the tendon (Fig. 6) and the steroid is injected.

Rheumatoid arthritis

This disease often affects the metatarsophalangeal joints.48 The usual signs and symptoms of an inflamed joint are seen. The patient has nocturnal pain and morning stiffness. Clinical examination reveals a capsular pattern and a capsular thickening at a warm and swollen joint. Treatment is causative.

Non-capsular patterns

Metatarsalgia

Treatment consists of an intra-articular injection of 10 mg of triamcinolone (see earlier). In a pes cavus deformity, the patient must also wear a raised heel with a horizontal upper surface (see Ch. 59). This measure relieves the excessive stress on the joint and prevents recurrences.

Sesamometatarsal lesions

Traumatic periostitis of the sesamoid bone of the flexor hallucis longus usually results from local trauma, such as stepping barefoot on a sharp pebblestone or landing on the medial side of the extended joint.49,50 After the accident the patient feels pain at the inner aspect of the forefoot with each step.

Clinical examination shows a full range of movement, sometimes with pain at the end of extension. Resisted flexion hurts at the plantar aspect and the sesamoid bone is tender to the touch, the exact point shifting with the position of the hallux.24 Clinical diagnosis can be confirmed with conventional radiography and MRI imaging.51,52

Treatment consists of infiltration of the correct area with 10 mg of triamcinolone. Usually one infiltration is sufficient. Some authors advise orthotics53 as a prophylactic measure but experience shows that this is never necessary. If conservative treatment is not followed by quick recovery, fracture54,55 or post-traumatic osteochondritis56 should be suspected. Immobilization in a plaster cast or surgical intervention is then required. Surgical treatment may include partial or complete resection of the sesamoid, shaving of a prominent tibial sesamoid or autogenous bone grafting for non-union.49

Alternatively, the pain can be caused by overuse, which sets up a traumatic arthritis at the sesamoid–first metatarsal joint.57,58 This condition is similar to metatarsalgia of the big toe. Treatment is an infiltration with 10 mg of triamcinolone between the sesamoid and the first metatarsal, together with prevention by use of a raised horizontal heel.

Technique: infiltration and injection

The patient lies supine on a high couch. The tender point is identified. Because the skin is usually thick and difficult to sterilize, the medial side of the metatarsophalangeal region must be scraped until the epidermis is clean. A 1 ml syringe is fitted to a thin needle and filled with 10 mg of triamcinolone. The insertion is made from the medial aspect. The thumb of the free hand is kept on the tender spot and the needle is advanced in the direction of the palpating thumb (Fig. 7), whether at the sesamoid bone or at the joint between sesamoid and metatarsal. Depending on the lesion, an infiltration or an injection is then made.

Halux valgus

This is the most common deformity of the big toe. It has been estimated that about 25% of the population have it to some degree.59 There is no parallel between the degree of valgus and the severity of the symptoms, and many patients with severe deformity are free of symptoms.

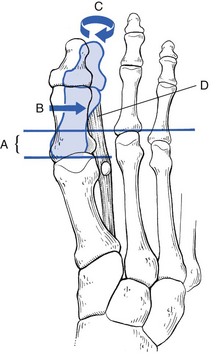

Much has been written about the aetiology of hallux valgus.60–62 Because hallux valgus also occurs in barefooted people who never wear shoes, there must be congenital factors predisposing to the deformity. The causative components seem to be multiple: the first metatarsal shaft is shorter than the second, there is a hypermobility of the first ray and the first intermetatarsal angle is enlarged.63,64 All these factors contribute to the origin of a widely splayed forefoot (A in Fig. 8).65,66 Because of the shortness of the first metatarsal, the second toe takes most of the weight during the final phase of the step. If there is a muscular imbalance between the adductor hallucis and abductor hallucis, the big toe will deviate laterally (B) and undergoes a pronation movement (C).67 This is accentuated by the contractions of the flexors and long extensor of the toe, which act like a bowstring and shift the tip of the big toe further into adduction (D). When this predisposed splayed forefoot is now forced into a high-heeled pointed shoe, excessive weight is added and the first toe deviates increasingly and rapidly in a lateral direction. The pointed shoe increases the pressure at the medial aspect of the metatarsophalangeal joint, which results in an inflamed and painful bursa (tailor’s bunion).68, 69

The diagnosis is made on the typical appearance:

• The forefoot is broadened and the transverse arch flattened.

• The big toe is angled towards the second toe and frequently overlies it. The medial portion of the first metatarsal head is enlarged.

• The skin and the bursa over the medial aspect of the first metatarsophalangeal joint are inflamed and thickened.

Treatment depends on the degree of disability. It is as well to remember that many patients with extreme deformities have no pain at all. Because most of the pain stems from the compression of the enlarged forefoot in too narrow shoes, the primary conservative treatment is appropriate shoes: a wide shoe with a horizontal heel should be advised; sometimes a ‘pouch’ can be pressed out at the side of the metatarsal head. Local tenderness at the skin or at the inflamed bursa can often be treated successfully with ichthammol ointment. Surgery is indicated when there is continuous pain or for cosmetic reasons.70–73 There is a choice of several procedures depending on the severity of the lesion and the age and mobility of the patient.74,75

The outer four metatarsophalangeal joints

The capsular pattern

The capsular pattern at the outer metatarsophalangeal joints is more limitation of flexion than extension (Fig. 9).

Freiberg’s osteochondritis

This is an ischaemic epiphyseal necrosis of the head of the second metatarsal bone, first described by Freiburg in 1914,76 and later by Kohler,77,78 who showed that the third instead of the second metatarsal is involved in about 20% of cases. The disease occurs in adolescence, before the epiphyseal closure of the metatarsal head has been completed.79

The precise aetiology is unknown but it is assumed that the development is precipitated by an abnormally long second metatarsal bone, indirect trauma and changes in bone marrow pressure.80,81 Sometimes the disease is asymptomatic until adulthood, when deformity of the involved metatarsal head and osteoarthrosis supervene and cause symptoms.

If the condition itself causes symptoms, examination will show localized arthritis of the second (or third) metatarsophalangeal joint, with local swelling and warmth and limitation of flexion and extension. It takes a month from the onset of pain before the characteristic radiographic changes become visible. Therefore, in its early stages the lesion is difficult to diagnose and a scintigraph or MRI image may be needed to distinguish it from a march fracture of the metatarsal shaft.82,83

Treatment consists of using orthotic metatarsal platforms to release pressure on the second metatarsal head. If there is limitation of extension, a ‘rocker’, as in hallux rigidus, can be prescribed. In advanced cases, surgery may be necessary.84

Traumatic arthritis

Traumatic arthritis at a metatarsophalangeal joint is rare. It can result from a direct blow or from indirect trauma, for instance during a hyperextension movement.85 Recently, hyperplantiflexion injuries to the great toe sustained in beach volleyball players have been described. This injury is referred to as ‘sand toe’ and may result in significant functional disability.86 Untreated, the capsulitis can continue for months, whereas one injection with 5 mg of triamcinolone can completely relieve pain within 2 days.

Non-capsular patterns

Chronic metatarsalgia

Aetiology

Scranton87 differentiates secondary and primary metatarsalgia. In the former, the lesion is the result of structural changes in the joint (e.g. Freiberg’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis or gout). The latter occurs if there is any incongruence between load and load-bearing capacity.

The aetiology of primary metatarsalgia is as follows. In a normal foot, only one-third of the body weight is borne by the forefoot. The transverse arch and the contraction of the long flexor muscles of the toes distribute the weight between the pads of the toes and the metatarsophalangeal joints. Because of the tautness of the anterior arch, the big toe and the outer toe take most of the weight. When too much weight falls on the forefoot, flattening of the anterior arch and insufficiency of the flexor muscles of the toes results in abnormal pressure on the plantar aspects of the second, third and fourth metatarsophalangeal joints.88,89 In due course, a local capsulitis develops. This happens in the following conditions:

• Splay foot: the broadened forefoot, associated with weakness of the intrinsic flexor muscles leads to flattening of the anterior arch and some clawing of the toes.

• Plantar deformity: the dropped forefoot leads to too much pressure at the plantar aspects of the metatarsophalangeal capsules.

• High heels: if the shoe has a high heel with an oblique upper surface, the patient will stand on an inclined plane, sliding constantly downwards on the forefoot. Too much weight is imposed on the forefoot, with chronic metatarsalgia as a result. It is not the high heel itself but the oblique upper surface which is the source of the trouble. High heels with a horizontal upper surface do not cause problems and are even beneficial to women with a plantaris deformity of the forefoot. Unfortunately, no such ready-made shoes exist.

• Pes cavus deformity: a pes cavus deformity is very often accompanied by extreme hyperextension at the metatarsophalangeal joints, caused by shortening of the extensor digitorum muscles together with ineffective intrinsic flexors, holding the toes clawed.90 In such cases, the toes do not bear body weight at all and serious metatarsalgia results, with large callosities under the metatarsal heads, together with corns at the dorsal aspects of the interphalangeal joints.

• Weak flexor muscles: sometimes the short muscles in the sole of the foot are weakened after a long rest in bed during an illness. If too much weight is borne too soon for too long a time, metatarsalgia can result.

• Dancer’s metatarsalgia: a dancer working en pointe may bruise the plantar aspect of the second, third and fourth metatarsophalangeal joints.91 To prevent this, most ballet shoes are fitted with a small semilunar pad, which ensures that the joints are protected and the body weight distributed as widely as possible.

Interdigital ganglion

A ganglion arising from a flexor tendon sheath may arise between the toes at the dorsum of the foot. It can cause painful pressure, especially if small shoes are worn.92 The diagnosis is obvious when a firm mass appears during standing. An excessive interval is then seen between the two toes and palpation reveals a semisolid tumour. Lying down permits the ganglion to recede. Because the mass is thick and composed of fibrolipomatous material, aspiration often fails. Excision is indicated if problems persist.

Bruising of the second digital nerve

During clinical examination the symptoms can be reproduced by local pressure on the bruised nerve.

Morton’s metatarsalgia

This condition, first described in 1876,93 results from a neuroma at the interdigital nerve between the fourth and fifth toes (exceptionally between the third and fourth toes).

Clinical examination is negative in most cases. Sometimes the symptoms can be reproduced by moving the heads of the adjacent metatarsal bones against each other during compression. Recently, ultrasound examination has been shown to be very sensitive in the detection of web-space abnormalities.94,95

The cause was described by Betts in 1940,96 who stated that the painful condition results from a fusiform neuroma, about 1 cm long, of the fourth digital nerve proximal to its point of division.97 When the fibrous swelling is nipped between the adjacent metatarsal heads, or pulled against a swollen transverse ligament,98 sudden ‘neuritic’ pain results.

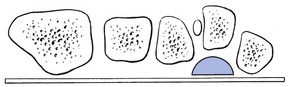

Treatment consists of relieving the pressure on the neuroma by alternating the alignment of the metatarsal heads. For instance, the head of the fourth bone can be elevated by a small support (Fig. 10). This will keep the bones slightly out of line and prevent pressure on the nerve. Steroid infiltration seldom succeeds. When conservative treatment fails, surgical excision of the neuroma may be required.99,100

References

1. Breithaupt, HS. Zur pathologie des Menschlichen Fusses. Med Ztg. 1855; XXIV:169–175.

2. Stechow. Sussödem und Röntgenstrahlen. Dtsch Mil-Aeztl. Zeitung. XXVI, 1897.

3. Iwamoto, J, Takeda, T, Stress fractures in athletes: review of 196 cases. J Orthop Sci 2003; 8:273–278. ![]()

4. Fetzer, GB, Wright, RW, Metatarsal shaft fractures and fractures of the proximal fifth metatarsal. Clin Sports Med 2006; 25:139–150. ![]()

5. Weinfeld, S, Haddad, S, Myerson, M. Stress fractures. Clin Sports Med. 1997; 16:319–338.

6. McBryde, AM, Stress fractures in runners. Clin Sports Med 1985; 4:737–752. ![]()

7. Milgrom, C, Giladi, M, Stein, M, et al, Stress fractures in military recruits. A prospective study showing an unusually high incidence. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1985; 67:732–735. ![]()

8. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol. 1, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

9. Holder, LE, Radionuclide bone-imaging in the evaluation of bone pain. J Bone Joint Surg 1982; 64A:1391–1396. ![]()

10. Gaeslien, GE, Early detection of stress fractures, using 99mTc-polyphosphate. Radiology 1976; 211:235–236. ![]()

11. Nitz, A, Scoville, CR, Use of ultrasound in early detection of stress fractures of the medial tibial plateau. Mil Med 1980; 145:844–846. ![]()

12. Ros, HP. Ultrageluid als screeningsprocedure bij stress-fracturen. Ned Tijdschr Fysiother. 1985; 95(10):206–209.

13. Gilaldi, M, Nili, E, Ziv, Y, Danon, YL, Aharonson, Z, Comparison between radiography, bone scan and ultrasound in the diagnosis of stress fractures. Mil Med 1984; 149:459–461. ![]()

14. Lawrence, SJ, Botte, MJ, Jones’ fractures and related fractures of the proximal fifth metatarsal. Foot Ankle 1993; 14:358–365. ![]()

15. Rosenberg, GA, Sferra, JJ, Treatment strategies for acute fractures and nonunions of the proximal fifth metatarsal. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2000; 8:332–338. ![]()

16. Fetzer, GB, Wright, RW, Metatarsal shaft fractures and fractures of the proximal fifth metatarsal. Clin Sports Med 2006; 25:139–150. ![]()

17. Konkel, KF, Menger, AG, Retzlaff, SA, Nonoperative treatment of fifth metatarsal fractures in an orthopaedic suburban private multispeciality practice. Foot Ankle Int 2005; 26:704–707. ![]()

18. Nunley, JA, Fractures of the base of the fifth metatarsal: The Jones fracture. Orthop Clin North Am 2001; 32:171–180. ![]()

19. Dameron, TB, Jr., Fractures of the proximal fifth metatarsal: selecting the best treatment option. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1995; 3:110–114. ![]()

20. Rosenberg, GA, Sferra, JJ, Treatment strategies for acute fractures and nonunions of the proximal fifth metatarsal. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8(5):332–338. ![]()

21. Hetherington, VJ, Carnett, J, Patterson, BA, Motion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. J Foot Surg. 1989;28(1):13–19. ![]()

22. Joseph, J. Range of motion of the great toe in men. J Bone Joint Surg. 1954; 36B:450–457.

23. Stokes, IAF, Hutton, WC, Stott, JR, Forces acting on the metatarsals during normal walking. J Anat 1979; 129:579–590. ![]()

24. Shereff, MJ, Begjiani, FJ, Kummer, FJ, Kinematics of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. J Bone Joint Surg 1986; 68A:392–398. ![]()

25. Dieppe, PA, Calvent, P. Crystals and Joint Disease. London: Chapman & Hall; 1982.

26. Seegmiller, JE, The acute attack of gouty arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1965; 8:714. ![]()

27. Yu, TF, Gutman, AB, Principles of current management of primary gout. Am J Med Sci 1967; 254:893. ![]()

28. Gast, LF, Cats, A, Geneesmiddelen tegen Jicht. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1988;132(40):1827–1831. ![]()

29. Klinenberg, JR, Goldfinger, S, Seegmiller, JE, The effectiveness of the xanthine oxidase inhibitor allopurinol in the treatment of gout. Ann Intern Med 1965; 62:639. ![]()

30. Goodfellow, J, Aetiology of hallux rigidus. Proc R Soc Med 1965; 59:821. ![]()

31. Smith, RW, Katchis, SD, Ayson, LC, Outcomes in hallux rigidus patients treated nonoperatively: a long-term follow-up study. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21(11):906–913. ![]()

32. Mann, RA, Clanton, TO, Hallux rigidus: treatment by cheilectomy. J Bone Joint Surg 1988; 70A:400–406. ![]()

33. Love, TR, Whynot, AS, Farine, I, Keller athroplasty: a prospective review. Foot Ankle 1988; 8:46–54. ![]()

34. Hamilton, WG, Hubbard, CE, Hallux rigidus. Excisional arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Clin. 2000;5(3):663–671. ![]()

35. Southgate, JJ, Urry, SR, Hallux rigidus: the long-term results of dorsal wedge osteotomy and arthrodesis in adults. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1997;36(2):136–140. ![]()

36. Coker, TP, Arnold, JA, Weber, DL, Traumatic lesions of the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe in athletes. Am J Sports Med 1978; 6:326–334. ![]()

37. Clanton, TO, Butler, JE, Eggert, A, Injuries to the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe in athletes. Am J Sports Med 1978; 6:326–334. ![]()

38. Rodeo, SA, O’Brien, S, Warren, RF, et al, Turf-toe: an analysis of metatarsophalangeal joint sprains in professional football players. Am J Sports Med 1990; 18:280–285. ![]()

39. Clanton, TO, Ford, JJ, Turf toe injury. Clin Sports Med. 1994;13(4):731–741. ![]()

40. Coughlin, MJ, Shurnas, PS, Hallux rigidus: demographics, eitology and radiographic assessment. Foot Ankle Int 2003; 24:731–743. ![]()

41. Camasta, CA, Hallux limitus and hallux rigidus. Clinical examination, radiographic findings, and natural history. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1996;13(3):423–448. ![]()

42. Zollinger, H, Hallux rigidus and its treatment. Ther Umsch. 1991;48(12):832–835. ![]()

43. Maher, A. An audit of the use of sodium hyaluronate 1% (Ostenil® Mini) therapy for the treatment of hallux rigidus. Br J Podiatry. 2007; 10:47–51.

44. Pons, M, Alvarez, F, Solana, J, Viladot, R, Varela, L, Sodium hyaluronate in the treatment of hallux rigidus. A single-blind, randomized study. Foot Ankle Int 2007; 28:38–42. ![]()

45. Mink, AJF, ter Veer, HJ, Vorselaars, JA. Extremiteiten; Functie-onderzoek en Manuele Therapie. Utrecht: Bonn Scheltema and Holkema; 1990.

46. Smith, RW, Joanis, TL, Maxwell, PD, Great toe metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis: a user-friendly technique. Foot Ankle. 1992;13(7):367–377. ![]()

47. Schenk, S, Meizer, R, Kramer, R, Aigner, N, Landsiedl, F, Steinboeck, G, Resection arthroplasty with and without capsular interposition for treatment of severe hallux rigidus. Int Orthop. 2009;33(1):145–150. ![]()

48. van der Leeden, M, Steultjens, MP, Ursum, J, et al, Prevalence and course of forefoot impairments and walking disability in the first eight years of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(11):1596–1602. ![]()

49. Richardson, EG, Halucal sesamoid pain: causes and surgical treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7(4):270–278. ![]()

50. McBryde, AM, Jr., Anderson, RB, Sesamoid foot problems in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 1988;7(1):51–60. ![]()

51. Karasick, D, Schweitzer, ME, Disorders of the hallux sesamoid complex: MR features. Skeletal Radiol. 1998;27(8):411–418. ![]()

52. Taylor, JA, Sartoris, DJ, Huang, GS, Resnick, DL, Painful conditions affecting the first metatarsal sesamoid bones. Radiographics. 1993;13(4):817–830. ![]()

53. Axe, MJ, Ray, RL, Orthotic treatment of sesamoid pain. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(4):411–416. ![]()

54. Van Hal, ME, Keene, JS, Lange, TA, Clancy, WG, Jr., Stress fractures of the great toe sesamoids. Am J Sports Med 1982; 10:122–128. ![]()

55. Abraham, M, Sage, R, Lorenz, M, Tibial and fibular sesamoid fractures on the same metatarsal: a review of two cases. J Foot Surg 1989; 28:308–311. ![]()

56. Irvin, LM, Witt, CS, Zielsdorf, LM. Lesions of the metatarsophalangeal joints. J Foot Surg. 1985; 24(3):256–262.

57. Grace, DL, Sesamoid problems. Foot Ankle Clin. 2000;5(3):609–627. ![]()

58. Oloff, LM, Schulhofer, SD, Sesamoid complex disorders. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1996;13(3):497–513. ![]()

59. Nix, S, Smith, M, Vicenzino, B, Prevalence of hallux valgus in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res 2010; 3:21. ![]()

60. Chomeley, JA, Hallux valgus in adolescents. Proc R Soc Med 1958; 51:903. ![]()

61. Root, MC, Orien, WP, Weed, JH. Normal and Abnormal Function of the Foot: Clinical Biomechanics; vol. 2. Clinical Biomechanics, Los Angeles, 1977.

62. Kelikian, H. Hallux Valgus and Allied Deformities of the Forefoot and Metatarsalgia. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1965.

63. Myerson, MS, Badekas, A, Hypermobility of the first ray. Foot Ankle Clin. 2000;5(3):469–484. ![]()

64. D’Arcangelo, PR, Landorf, KB, Munteanu, SE, Zammit, GV, Menz, HB, Radiographic correlates of hallux valgus severity in older people. J Foot Ankle Res 2010; 3:20. ![]()

65. Glasoe, WM, Allen, MK, Saltzman, CL, First ray dorsal mobility in relation to hallux valgus deformity and first intermetatarsal angle. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22(2):98–101. ![]()

66. Tanaka, Y, Takakura, Y, Sugimotor, K, et al, Precise anatomic configuration changes in the first ray of the hallux valgus foot. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21(8):651–656. ![]()

67. Greensburg, GS, Relationship of hallux abductus angle and first metatarsal angle to severity of pronation. J Am Podiatr Assoc. 1976;69(1):29. ![]()

68. Mann, RA, Coughlin, MJ. Hallux valgus and complications of hallux valgus. In: Mann RA, ed. Surgery of the Foot. 5th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1986:65.

69. Schoenhaus, HD, Cohen, RS, Etiology of the bunion. J Foot Surg. 1992;31(1):25–29. ![]()

70. Johnson, KA. Chevron osteotomy of the first metatarsal: patient selection and technique. Contemp Orthop. 1981; 3:707.

71. McBride, ED. A conservative operation for bunions. J Bone Joint Surg. 1928; 10:735.

72. Mitchell, CL, Fleming, JL, Allen, R, et al, Osteotomy buniectomy for hallux valgus. J Bone Joint Surg 1958; 40A:4. ![]()

73. De Doncker, E, Kowalski, C, Le pied normal et pathologique. Notions d’anatomie, de physiologie et de pathologie des déformations du pied. Acta Orthop Belg 1970; 36:4–5. ![]()

74. Weil, LS, Scarf osteotomy for correction of hallux valgus. Historical perspective, surgical technique, and results. Foot Ankle Clin. 2000;5(3):559–580. ![]()

75. Zembsch, A, Trnka, HJ, Ritschl, P, Correction of hallux valgus. Metatarsal osteotomy versus excision arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 2000; 376:183–194. ![]()

76. Freiburg, AH. Interaction of the second metatarsal bone. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1914; 19:191.

77. Kohler, A. Typical disease of the second metatarsophalangeal joint. Am J Roentgenol. 1923; 10:705.

78. Hoskinson, J, Freiberg’s disease: review of long-term results. Proc R Soc Med 1974; 67:10. ![]()

79. Ficat, RP, Arlet, J. Ischemia and Necrosis of Bone. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1980.

80. Stanley, D, Betts, RP, Rowley, DI, Smith, TW, Assessment of etiologic factors in the development of Freibeig’s disease. J Foot Surg. 1990;29(5):444–447. ![]()

81. Beito, SB, Lavery, LA, Freiberg’s disease and dislocation of the second metatarsophalangeal joint: etiology and treatment. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1990;7(4):619–631. ![]()

82. Manusov, EG, Lillegard, WA, Raspa, RF, Epperly, TD, Evaluation of pediatric foot problems: Part I. The forefoot and the midfoot. Am Fam Phys. 1996;54(2):592–606. ![]()

83. Mandell, GA, Harcke, HT, Scintigraphic manifestations of infraction of the second metatarsal (Freiberg’s disease). J Nucl Med. 1987;28(2):249–251. ![]()

84. Chao, KH, Lee, CH, Lin, LC, Surgery for symptomatic Freiberg’s disease: extraarticular dorsal closing-wedge osteotomy in 13 patients followed for 2–4 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70(5):483–486. ![]()

85. Clanton, TO, Butler, JE, Eggert, A, Injuries to the metatarsophalangeal joints in athletes. Foot Ankle. 1986;7(3):162–176. ![]()

86. Frey, C, Andersen, GD, Feder, KS, Plantarflexion injury to the metatarsophalangeal joint (‘sand toe’). Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17(9):576–581. ![]()

87. Scranton, PE, Metatarsalgia. J Bone Joint Surg 1980; 62A:723. ![]()

88. Herschel, H, Van Meel, PJ, Metatarsalgie. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1982;126(45). ![]()

89. Bojsen Möller, F, Lamoreux, L, Metatarsalgia. Acta Orthop Scand 1979; 50:471. ![]()

90. Myerson, MS, Shereff, MJ, The pathological anatomy of claw and hammer toes. J Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71A(1):45–49. ![]()

91. Brok, AGM. Medische problemen bij ballet en andere dansvormen. Geneeskd Sport. 1983; 16:135–140.

92. Kulund, DN. Airplane insulation for flying feet. Athletic Training. 1979; 14(3):144–145.

93. Morton, TG. Peculiar painful affection of fourth metatarsophalangeal articulation. Am J Med Sci. 1876; 71:37.

94. Read, JW, Noakes, JB, Kerr, D, et al, Morton’s metatarsalgia: sonographic findings and correlated histopathology. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20(3):153–161. ![]()

95. Oliver, TB, Beggs, I, Ultrasound in the assessment of metatarsalgia: a surgical and histological correlation. Clin Radiol. 1998;53(4):287–289. ![]()

96. Betts, LO. Morton’s metatarsalgia: neuritis of the fourth digital nerve. Med J Aust. 1940; 1:514.

97. Morscher, E, Ulrich, J, Dick, W, Morton’s intermetatarsal neuroma: morphology and histological substrate. Food Ankle Int. 2000;21(7):558–562. ![]()

98. Bosley, CG, Cairney, PC. The intermetatarsophalangeal bursa. Its significance in Morton’s metatarsalgia. J Bone Joint Surg. 1980; 62B:184.

99. Dereymaeker, G, Schroven, I, Steenwerckx, A, Stuer, P, Results of excision of the interdigital nerve in the treatment of Morton’s metatarsalgia. Acta Orthop Belg. 1996;62(1):22–25. ![]()

100. Assmus, H, Morton metatarsalgia. Results of surgical treatment in 54 cases. Nervenarzt. 1994;65(4):238–240. ![]()