Chapter 32 Oesophagus, stomach and duodenum

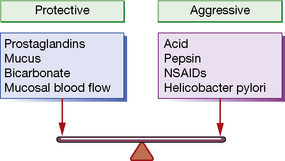

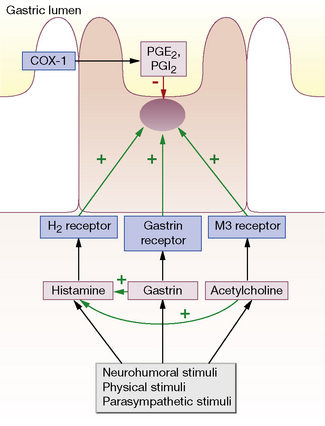

Gastric acid secretion and mucosal protection

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori): an occasionally silent killer

It is now known that a large majority of benign gastric and duodenal ulceration is due to H. pylori infection (following Marshall and Warren’s Nobel prize-winning experiments1,2); most of the remainder can be attributed to NSAID use. Colonisation of the stomach with H. pylori is seen in virtually all patients with a duodenal ulcer and in 70–80% of those with gastric ulcers. H. pylori appears to stimulate increased acid secretion. All patients colonised with H. pylori develop gastritis, but only about 20% have ulcers or other lesions. As yet incompletely understood host factors and differences in strain of the organism are likely to explain this discrepancy.

NSAIDs: enemies of the gut

Aspirin and the other NSAIDs inhibit cyclo-oxygenase (COX) (see Ch. 16). In the stomach, the constitutively expressed COX-1 isoform is responsible for the production of the gastroprotective prostaglandins E2 and I2 (see above). Inhibition of the inducible COX-2 isoform (which is normally up-regulated in activated inflammatory cells) is responsible for NSAIDs’ anti-inflammatory properties. Most NSAIDs inhibit both isoforms unselectively, so the beneficial anti-inflammatory effect is offset by the potential for mucosal injury by depletion of protective prostaglandins. Aspirin is particularly potent in this respect, perhaps because it inhibits COX irreversibly, unlike the other NSAIDs where inhibition is reversible and concentration dependent.

Drugs affecting oesophageal motility and the lower oesophageal sphincter

Newer therapies being explored in the treatment of GORD include GABA inhibition to reduce transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations. Baclofen (see p. 304) is clinically effective but has limiting CNS unwanted effects, and more tolerable compounds are being investigated. Other pharmacological targets which are showing potential in early clinical research include cannabinoid agonists.

Drugs to reduce or neutralise gastric acid

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

Pharmacology

As can be deduced from the above, the most effective site of action for antisecretory drugs is the proton pump. Proton pump inhibitors are taken up by parietal cells from the portal circulation and are then excreted into the acid milieu around the secretory canaliculus. The resulting ionised form binds irreversibly to the proton pump, resulting in virtual total inhibition of acid secretion (Fig 32.1).

H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs)

Drugs to enhance mucosal protection

Pharmacological management

Oesophageal dysmotility

Pharmacological management of achalasia3 is best viewed as a temporary measure and drugs which reduce LOS tone rarely provide effective symptomatic improvement. Botulinum toxin, which inhibits cholinergic transmission by reducing ACh release from pre-synaptic motor neurones (see Ch. 22), can be injected endoscopically into the LOS and results in medium-term (3–6 months) relaxation of the LOS and symptomatic improvement. Endoscopic dilatation or surgical correction results in longer-term improvement. Relaxation of the LOS results in potentially free reflux of gastric acid contents and must therefore be accompanied by a PPI.

Nausea and vomiting

The physiology of nausea and vomiting is complex and incompletely understood. Vomiting can be protective, e.g. when it expels toxins (such as food poisoning and alcohol) from the GI tract. Suppressing nausea and vomiting is important in the management of other conditions including chemotherapy, general anaesthesia, morning sickness of pregnancy and when it accompanies other disease states (e.g. cardiac ischaemia, migraine).4

Drugs used in nausea and vomiting

D2-receptor antagonists

These include the phenothiazines, also used as antipsychotics, such as chlorpromazine and haloperidol. They are powerful antiemetics but have relatively common and significant CNS side-effects including drowsiness and extrapyramidal movement disorders. Their pharmacology is discussed in detail in Chapter 20.

5-HT3-receptor antagonists

Drugs such as ondansetron are powerful and well tolerated agents which act at the CTZ.

Non-ulcer dyspepsia and functional disorders

Up to a third of patients presenting to secondary care with dyspeptic symptoms have no pathological cause identified and have ‘non-ulcer dyspepsia’. Management of these patients can be challenging and requires a comprehensive approach. Many patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia have abnormalities of gastric emptying and increased pain perception in the gastrointestinal tract, suggesting that the condition is part of the spectrum of irritable bowel syndrome (see Ch. 33).

Armstrong D., Sifrim D. New pharmacologic approaches in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am.. 2010;39:393–418.

Camilleri M., Tack J.F. Current medical treatments of dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am.. 2010;39:481–493.

McColl K.E. Helicobacter pylori infection. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2010;362:1597–1604.

Moayyedi P., Talley N. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 2006;367:2086–2100.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Dyspepsia: Managing Dyspepsia in Adults in Primary Care. London: NICE; 2004.

Richter J.E. Oesophageal motility disorders. Lancet. 2001;358:823–828.

Rotherberg M.E. Biology and treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(4):1238–1249.

White P.F. Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting – a multimodal solution to a persistent problem. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2004;350:2511–2515.

Yang Y.X., Metz D.C. Safety of proton pump inhibitor exposure. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1115–1127.

1 Marshall B J, Warren J R 1984 Unidentified curved bacillis in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet i:1311–1315. (Marshall deliberately infected himself by drinking a solution swimming with the bacterium, as part of a successful and widely reported experiment to prove Koch’s postulates.)

2 Pincock S 2005 Nobel Prize winners Robin Warren and Barry Marshall. Lancet 366:1429.

3 Characterised by incomplete relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS), increased LOS tone, lack of peristalsis in the oesophagus and consequent inability of smooth muscle to move food down the oesophagus.

4 The pharmacology of vomiting was little studied until the world war of 1939–1945, when motion sickness attained military importance as a possible handicap for sea landings made in the face of resistance. The British military authorities and the Medical Research Council therefore organised an investigation. Whenever there was a prospect of sufficiently rough weather, about 70 soldiers were sent to sea in small ships, again and again, after being dosed with a drug or a dummy tablet and having had their mouths inspected to detect non-compliance. The ships returned to land when up to 40% of the soldiers vomited. ‘On the whole the men enjoyed their trips’; some of them, however, being soldiers, thought the tablets were given in order to make them vomit and some ‘believed firmly in the efficacy of the dummy tablets’. It was concluded that, of the remedies tested, antimuscarinic drug hyoscine was the most effective. Holling H E, McArdle B, Trotter W R 1944 Prevention of seasickness by drugs. Lancet i:127.