Chapter 85 Ocular Toxoplasmosis

Introduction

Toxoplasmosis is a common zoonosis caused by the infection with Toxoplasma gondii, and it is also the most important and frequent cause of infectious retinal disease and posterior uveitis. Toxoplasmosis can cause severe, life-threatening disease, specially in newborns and immunosuppressed patients but the majority of T. gondii infections in immunocompetent patients remain asymptomatic.1,2

In the eye it can cause blindness secondary to the retinitis present in the posterior pole of the eye or vitreoretinal complications in the acute or recurrent form of the disease.3 Ocular toxoplasmosis (OT) represents 50–85% of the posterior uveitis cases in Brazil and about 25% of cases in the United States.4 The prevalence of OT in the United States is not well determined but it ranges from 0.6 to 2% according to published reports and in Brazil, the prevalence ranges from 10 to 17.7%.5

Ocular toxoplasmosis may occur either in a congenital or a postnatal acquired form, and in both the eye may be affected during the acute phase of the infection or, more commonly, many months to years later.6 Many concepts related to OT have changed in the last years and are presented in Box 85.1.

Beef probably is not an important source of transmission; undercooked lamb, pork, and chicken are the common culprits as well as food and environment contaminated by the feces of infected cats. Transmission can also occur via organ transplantation and blood transfusion.7 Recently, water has been associated with the transmission of ocular toxoplasmosis on different continents.8

Fetal toxoplasmosis tends to occur only when the woman acquires the infection during or months before the pregnancy. The infection may be severe and is a frequent cause of abortion in the first months of pregnancy. When the fetus is infected, OT may become clinically apparent decades later and when it does, it presents bilaterally 85% of the time.9 Even women with IgG serum antibodies against toxoplasma may not be always protected against transmitting congenital toxoplasmosis to the fetus.10

Biology, life cycle, and transmission

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate, intracellular protozoan parasite that undergoes a life cycle which includes both sexual and asexual reproduction. The sexual cycle occurs exclusively in felines, which shed a large number of infectious oocysts in their feces once in life, usually for a few weeks. Members of the cat family are its definitive hosts (hosts in which the parasite reproduces sexually), but hundreds of other species, including mammals, birds, and reptiles, may serve as intermediate hosts.11 The parasite can be found in the host’s tissues, such as muscles, retina, nervous system, and body fluids (saliva, milk, semen, urine, and peritoneal fluid).12

T. gondii exists in three forms: the oocyst, the tachyzoite, and the bradyzoite (also called the tissue cyst). Once the cyst is ingested by the intermediate hosts it causes disease with the production of tachyzoites. Under the pressure of the immune response the bradyzoites are formed. They are very resistant and may remain in the retina as well as the central nerve system and different muscles such as the tongue and heart for many years.13 The bradyzoites can remain dormant in the host for years without tissue damage and, for unknown causes, may rupture, causing reactivation of the ocular acute and recurrent disease.14

Strains/clonal populations: haplogroups genetics

The ability to identify parasite types may provide new insights into the pathogenesis of this disease, and genotyping ultimately may become an important diagnostic and prognostic tool.15

The majority of strains identified in Europe and North America are classified into three distinct genotypes (types I, II, and III). Type I strains are very virulent and types II and III strains are less virulent. All of them can cause disease in humans. Type I strains are considered to be more often associated with postnatal acquired ocular infections, and type II strains are more associated with congenital infections and toxoplasmic encephalitis.16 Atypical strains as well as mixed infections have been identified in many parts of the world and these atypical strains seem to be common in Brazil.17 The genetic make up of T. gondii is more complex than previously recognized and unique or divergent genotypes may contribute to different clinical outcomes of toxoplasmosis in different localities.18

Atypical toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis as well as variations in the clinical presentation and severity of disease have been attributed to several factors, including the genetic heterogeneity of the host and the genotype of the parasite responsible for infection.19

Pathogenesis

Serologic evidence of previous toxoplasma infection is present in 20–70% of individuals in different countries, depending on a variety of factors including climate, hygiene, and dietary habits. There is no consistent correlation between the prevalence of serum antibodies and the frequency of ocular disease.20 Different factors, such as the pathogenicity of the toxoplasmosis strains, may play an important role.21

Ocular toxoplasmosis in immunocompetent patients is characterized histologically by foci of granulomatous chorioretinal inflammation and coagulative necrosis of the retina with sharply demarcated borders. Inflammatory changes can be widespread in the eye and involve choroid, iris, and trabecular meshwork. Immunosuppressed patients with ocular toxoplasmosis have both tachyzoites and tissue cysts in areas of retinal necrosis and within retinal pigment epithelial cells.22 Parasites can occasionally be found in the iris, choroid, vitreous, and optic nerve. The lesions tend to be diffuse and often are active in both eyes.23,24

Ocular disease

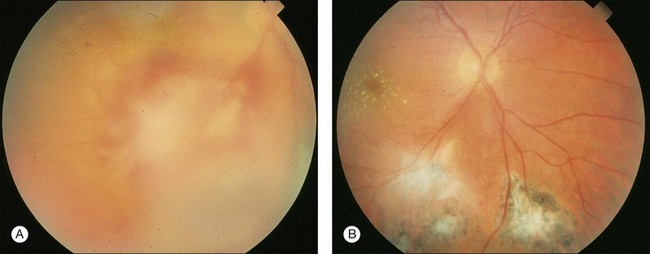

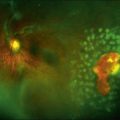

The retina is the primary site of T. gondii infection in the eye and the hallmark is a necrotizing retinochoroiditis satellite lesion adjacent to old hyperpigmented scars accompanied by vitreous inflammation and anterior uveitis. Retinal vasculitis is also present (Fig. 85.1). OT is characterized by recurrent episodes of necrotizing retinochoroiditis thought to be caused by the proliferation of live organisms that emerge from tissue cysts and/or an inflammatory reaction triggered by autoimmune mechanisms.25

The most common clinical signs of active ocular toxoplasmosis are blurring or loss of vision and floaters. Depending on the location of the lesions and the anterior chamber and vitreous inflammation patients can be more or less symptomatic.26

The diagnosis is clinical and suspected based on the ocular examination, the exclusion of the differential diagnostic entities (see below), and the presence of circulating antibodies for toxoplasmosis. It is important to perform both biomicroscopy and indirect ophthalmoscopy in both eyes. In special cases other procedures such as optical coherence tomography or fluorescein angiography may be necessary to diagnose and manage complications like macular edema and vasculitis.27 Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis can be associated with severe morbidity if disease extends to structures critical for vision, including the macula and optic nerve, if there is damage to the eye from inflammation or if there are complications such as retinal detachment due to necrotic hole formation or tractional changes or neovascularization.28

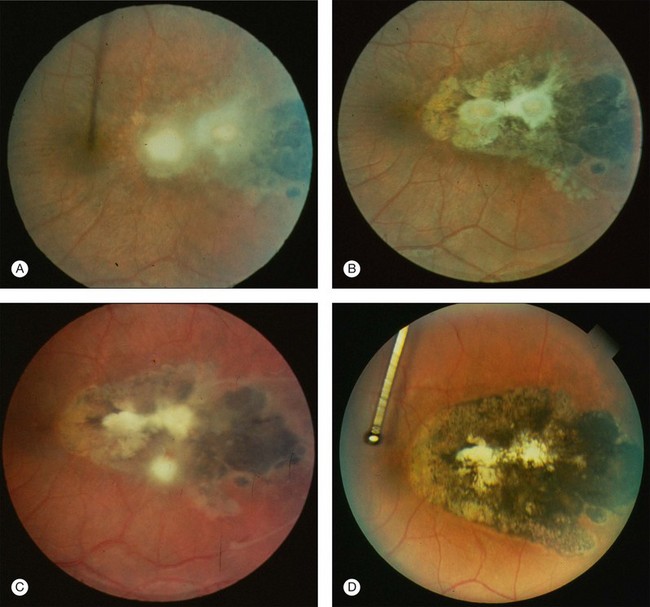

Recurrence frequency varies between individuals and is unpredictable, not only with respect to frequency but also regarding the retina site and its clinical presentation29 (Fig. 85.2).

Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis lesions have the same fundus characteristics, whether they result from congenital or acquired infections (Fig. 85.3). Acute and new lesions are usually intensely white, focal lesions with overlying vitreous inflammatory haze. Active lesions that are accompanied by a severe vitreous inflammatory reaction will have the classic “headlight in the fog” appearance. Anterior uveitis is characterized by inflammatory cells in the aqueous, medium-sized keratic precipitates, and posterior synechiae.30

Eyes with active toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis will occasionally develop retinal vasculitis with vascular sheathing and hemorrhages in response to reactions between circulating antibodies and local T. gondii antigens.31 Typically, hyperpigmented scars of old and inactive lesions are present, and recurrent lesions occur at the border of healed scar as a satellite lesion.32

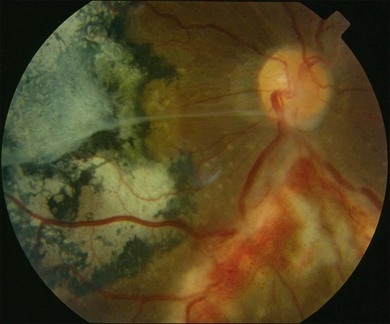

In most cases toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis is a self-limited disease. Untreated lesions generally begin to heal after 1 or 2 months, although the time course is variable, and in some cases active disease may persist for months.33 HIV-infected patients have a tendency to present with diffuse retinitis with less vitreous involvement since they do not generate a vigorous inflammatory response. A high number of recurrences may be seen (Figs 85.4 and 85.5).

As a lesion heals, its borders become more defined and after several months may become hyperpigmented. Large scars will have an atrophic center that is devoid of all retinal and choroidal elements; the underlying sclera gives the lesion its white center.34 Recent evidence has also suggested that patients with recent acquired infection may present with vitritis or even anterior uveitis in the absence of retinochoroiditis.35

The association between Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis and ocular toxoplasmosis has been reported in different countries and the pathologic mechanisms remain unknown.36

Laboratory techniques

Parasites are found rarely in intraocular fluids, and invasive diagnostic tests such as retinal biopsy are associated with serious risks that prevent their routine use. Different serologic tests exist and should be used only to confirm past exposure to T. gondii; it is inappropriate to base a diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis on the presence of antibodies alone. There is no minimal level of antibodies necessary to make the diagnosis of OT; any positive serology is enough therefore to diagnose ocular toxoplasmosis. The IgG serum antibodies can persist at high titers for years after an acute infection, and there is a high prevalence of such antibodies in the general population. Because active retinal lesions are usually foci of recurrent disease, serum IgG titers may be low and IgM may be absent. The serologic determination of IgA antibodies may help to determine the time of the primary infection since they last for less time in the serum.37

The development of molecular biology techniques has allowed the identification of T. gondii DNA in the aqueous humor and the vitreous, as well as ocular tissue sections of patients with presumed toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis, by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques even when organisms are not identified on histopathologic examination.38,39

The differential diagnoses comprise infectious diseases such as rubella, cytomegalovirus, syphilis, herpes simplex, tuberculosis, and toxocariasis. Noninfectious conditions like retinal and choroidal coloboma, retinoblastoma, retinopathy of prematurity, gyrate atrophy, retinal vascular membrane, and serpiginous choroidopathy among others have to be excluded in some presentations.40

Outcomes and complications

Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis can result in permanent loss of vision because of retinal necrosis, uveitis, and its complications. Central vision will be lost if lesions affect the fovea, maculopapillary bundle, or optic disc. Other reported complications include macular edema, retinal neovascularization, vascular occlusion and vitreoretinal lesions such as vitreous hemorrhage and epiretinal membranes. Subretinal neovascular membranes may be a cause of sudden loss of vision. Rhegmatogenous and tractional retinal detachments may occur as well as secondary glaucoma and cataracts.41

Treatment and prevention

There are many questions surrounding the treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis. Available drugs do not eliminate tissue cysts and cannot prevent chronic infection. No treatment has proven to be superior or even more effective than no treatment. It is accepted that steroids decrease the inflammation and therefore can lead to better vision function but should not be used without antitoxoplasmic drugs in order to avoid the worsening of the infection.42 But the efficacy of the antitoxoplasmic agents and systemic steroids have never been studied in large clinical trials. There is no cure for toxoplasmosis since the tissue cysts are resistant to the available drugs and remain viable for many years.43

The combination of pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and corticosteroids, which is considered the “classic” therapy for ocular toxoplasmosis (Box 85.2), is the most common drug combination used and considered by many experts to be the best option.44 Therapy with trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole probably is equally effective and has fewer side-effects and better patient compliance. It may be considered, however, as having a higher risk to cause severe allergic reactions because of the long life of sulfamethoxazole.45 Other drugs, such as systemic or intraocular clindamycin, have also been used.46,47

Box 85.2

Classic therapy for ocular toxoplasmosis

• Pyrimethamine: 75–100 mg loading dose given over 24 hours, followed by 25–50 mg daily for 4–6 weeks depending on clinical response

• Sulfadizine: 2.0–4.0 g loading dose initially, followed by 1.0 g given 4 times daily for 4–6 weeks, depending or clinical response

• Prednisone: 40–60 mg daily for 2 to many weeks depending on clinical response; taper off before discontinuing pyrimethamine/sulfadiazine

• Folinic acid: 5.0 mg tablet, 2–3 times weekly during pyrimethamine therapy

The duration of treatment depends on the individual clinical picture. Steroid treatment is often administered systemically and, as noted above, always associated with antitoxoplasmic drugs. Local drops are used when anterior uveitis is present.48

Traditional short-term treatments of active toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis lesions do not prevent subsequent recurrences. There is no cure for OT since none of the available drugs penetrates the cyst.49

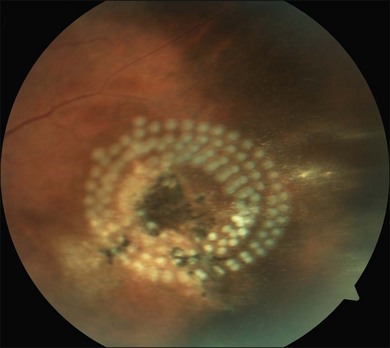

The combination of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole given for many months may decrease the number of recurrences and should be considered in higher-risk patients.50 Periodical evaluation of the retina is mandatory in order to diagnose and treat potential sight-threatening complications such as retinal holes and retinal detachments (Fig. 85.6).

Classically, toxoplasmosis was considered as a self-limiting benign infection in the normal host, with treatment not necessary. Prevention of ocular toxoplasmosis in all patients with the acute form of systemic infection is debatable. Opinion is divided whether treatment should be offered in cases of recent acquired toxoplasmosis to decrease the population of tissue by cysts, thereby avoiding or decreasing later ocular involvement,51 since its effectiveness has never been demonstrated.

When indicated, cataract surgery should be performed to restore vision and to allow the fundus examination in order to identify new lesions as well as retinal complications secondary to the uveitis. As a rule, patients with cataract secondary to ocular toxoplasmosis are operated on, typically with IOL (intraocular lens) implantation with good results, after at least 3 months of the uveitis being inactive.52

1 Weiss LM, Dubey JP. Toxoplasmosis: A history of clinical observations. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39(8):895–901. Review

2 Commodaro AG, Belfort RN, Rizzo LV, et al. Ocular toxoplasmosis: an update and review of the literature. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(2):345–350. Review

3 Nussenblatt RB. Ocular toxoplasmosis. In: Nussenblatt RB, Whitcup SM, Palestine AG. Uveitis: fundamentals and clinical practice. 2nd ed. St Louis: Mosby–Year Book; 1996:211–228.

4 Jones JL, Kruszon-Moran D, Wilson M, et al. Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States: seroprevalence and risk factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:357–365.

5 Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment. Part I: epidemiology and course of disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(6):973–988.

6 Holland GN, O’Connor GR, Belfort R, et al. Toxoplasmosis. In: Pepose JS, Holland GN, Wilhelmus KR. Ocular infection and immunity. St Louis: Mosby–Year Book; 1996:1183–1223.

7 Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 2004;363:1965–1976. Review

8 Bowie WR, King AS. Outbreak of toxoplasmosis associated with municipal drinking water. Lancet. 1997;350:173–178.

9 Garza-Leon M, Muccioli C, Arellanes-Garcia L. Toxoplasmosis in pediatric patients. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2008;48:75–85.

10 Silveira C, Ferreira R, Muccioli C, et al. Toxoplasmosis transmitted to a newborn from the mother infected 20 years earlier. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003 Aug;136(2):370–371.

11 Remington JS, McLeod R, Thulliez P, et al. Toxoplasmosis. In: Remington JS, Klein J. Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant. 5th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2001:205–346.

12 Belfort R, Jr., Muccioli C. Toxoplasmosis ocular. Uveítis y Tumores Intraoculares Temas Selectos. Fernando Arévalo J, Graue-Wiechers F, Quiroz-Mercado H, et al, eds. Uveítis y Tumores Intraoculares Temas Selectos. Venezuela: AMOLCA; 2008;vol. 1:81–88.

13 Tenter AM, Heckeroth AR, Weiss LM. Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30(12–13):1217–1258.

14 Silveira C, Vallochi AL, Rodrigues da Silva U, et al. Toxoplasma gondii in the peripheral blood of patients with acute and chronic toxoplasmosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(3):396–400.

15 Howe DK, Honoré S, Derouin F, Sibley LD. Determination of genotypes of Toxoplasma gondii strains isolated from patients with toxoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(6):1411–1414.

16 Vallochi AL, Muccioli C, Martins MC, et al. The genotype of Toxoplasma gondii strains causing ocular toxoplasmosis in humans in Brazil. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(2):350–351.

17 Vaudaux JD, Muccioli C, James ER, et al. Identification of an atypical strain of toxoplasma gondii as the cause of a waterborne outbreak of toxoplasmosis in Santa Isabel do Ivai, Brazil. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(8):1226–1233.

18 Grigg ME, Ganatra J, Boothroyd JC, et al. Unusual abundance of atypical strains associated with human ocular toxoplasmosis. J Infect Dis. 2001;184(5):633–639.

19 Bottós J, Miller RH, Belfort RN, et al. UNIFESP Toxoplasmosis Group. Bilateral retinochoroiditis caused by an atypical strain of Toxoplasma gondii. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(11):1546–1550.

20 Talabani H, Asseraf M, Yera H, et al. Contributions of immunoblotting, real-time PCR, and the Goldmann–Witmer coefficient to diagnosis of atypical toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(7):2131–2135.

21 Saeij JP, Boyle JP, Boothroyd JC. Differences among the three major strains of Toxoplasma gondii and their specific interactions with the infected host. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:476–481.

22 Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment. Part II: disease manifestations and management. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:1–17.

23 Holland GN, Engstrom RE, Jr., Glasgow BJ, et al. Ocular toxoplasmosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106(6):653–667.

24 Rehder JR, Burnier MB, Jr., Pavesio CE, et al. Acute unilateral toxoplasmic iridocyclitis in an AIDS patient. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106(6):740–741.

25 Arevalo JF, Belfort R, Jr., Muccioli C, et al. Ocular toxoplasmosis in the developing world. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010;50(2):57–69. Review

26 Bonfioli AA, Orefice F. Toxoplasmosis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2005;20(3):129–141. Review

27 Pereira A, Orefice F. Toxoplasmosis. In: Foster CS, Vitale AT. Diagnosis and treatment of uveitis. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 2001:385–410.

28 Bosch-Driessen LH, Karimi S, Stilma JS, et al. Retinal detachment in ocular toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(1):36–40.

29 Holland GN, Crespi CM, ten Dam-van Loon N, et al. Analysis of recurrence patterns associated with toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(6):1007–1013.

30 Rothova A. Ocular manifestations of toxoplasmosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2003;14(6):384–388. Review

31 Smith JR, Cunningham ET, Jr. Atypical presentations of ocular toxoplasmosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13(6):387–392. Review

32 Hovakimyan A, Cunningham ET, Jr. Ocular toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2002;15(3):327–332. Review

33 Tabbara KF. Ocular toxoplasmosis. Int Ophthalmol. 1990;14(5–6):349–351. Review

34 Pleyer U, Torun N, Liesenfeld O. [Ocular toxoplasmosis.]. Ophthalmologe. 2007;104(7):603–615. quiz 616. Review

35 Holland GN, Muccioli C, Silveira C, et al. Intraocular inflammatory reactions without focal necrotizing retinochoroiditis in patients with acquired systemic toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128(4):413–420.

36 Toledo de Abreu M, Belfort R, Jr., Hirata PS. Fuchs’ heterochromic cyclitis and ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93(6):739–744.

37 Vallochi AL, Nakamura MV, Schlesinger D, et al. Ocular toxoplasmosis: more than just what meets the eye. Scand J Immunol. 2002;55:324–328.

38 Matos K, Muccioli C, Belfort R, Jr., et al. Correlation between clinical diagnosis and PCR analysis of serum, aqueous, and vitreous samples in patients with inflammatory eye disease. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2007;70:109–114.

39 Fekkar A, Bodaghi B, Touafek F, et al. Comparison of immunoblotting, calculation of the Goldmann–Witmer coefficient, and real-time PCR using aqueous humor samples for diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(6):1965–1967.

40 Vasconcelos-Santos DV, Dodds EM, Oréfice F. Review for disease of the year: differential diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011;19(3):171–179.

41 London NJ, Hovakimyan A, Cubillan LD, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and causes of vision loss in patients with ocular toxoplasmosis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(6):811–819.

42 Stanford MR, Gilbert RE. Treating ocular toxoplasmosis: current evidence. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(2):312–315. Review

43 Stanford MR, See SE, Jones LV, et al. Antibiotics for toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis: an evidence-based systematic review. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:926–931. quiz 931–2. Review

44 Rothova A, Meenken C, Buitenhuis HJ, et al. Therapy for ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;115:517–523.

45 Soheilian M, Sadoughi MM, Ghajarnia M, et al. Prospective randomized trial of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole versus pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine in the treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(11):1876–1882.

46 Soheilian M, Ramezani A, Azimzadeh A, et al. Randomized trial of intravitreal clindamycin and dexamethasone versus pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and prednisolone in treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(1):134–141.

47 Lasave AF, Díaz-Llopis M, Muccioli C, et al. Intravitreal clindamycin and dexamethasone for zone 1 toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis at twenty-four months. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(9):1831–1838.

48 Bosch-Driessen EH, Rothova A. Sense and nonsense of corticosteroid administration in the treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:858–860.

49 Holland GN, Crespi CM, ten Dam-van Loon N, et al. Analysis of recurrence patterns associated with toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(6):1007–1013.

50 Silveira C, Belfort R, Jr., Muccioli C, et al. The effect of long-term intermittent trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole treatment on recurrences of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:41–46.

51 McLeod R, Kieffer F, Sautter M, et al. Why prevent, diagnose and treat congenital toxoplasmosis? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(2):320–344.

52 Van Gelder RN, Leveque TK. Cataract surgery in the setting of uveitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20(1):42–45.