34

Obstetric haemorrhage

Introduction

Obstetric haemorrhage is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality worldwide, and even in the more affluent societies, with ready access to resuscitation, uterotonics, blood transfusion and surgery, deaths still occur. Haemorrhage may be of rapid onset. It is important to recognize its severity promptly, institute effective therapy and keep ahead of the loss.

A vaginal examination should not be performed in the presence of antepartum vaginal bleeding without first excluding placenta praevia – ‘No PV until no PP’.

Definitions

Vaginal bleeding associated with intrauterine pregnancy is divided into the following categories:

![]() threatened miscarriage – up to 24 weeks’ gestation

threatened miscarriage – up to 24 weeks’ gestation

![]() antepartum haemorrhage – from 24 weeks’ gestation until the onset of labour

antepartum haemorrhage – from 24 weeks’ gestation until the onset of labour

![]() intrapartum haemorrhage – from the onset of labour until the end of the second stage

intrapartum haemorrhage – from the onset of labour until the end of the second stage

![]() postpartum haemorrhage – from the third stage of labour until the end of the puerperium (6 weeks after delivery).

postpartum haemorrhage – from the third stage of labour until the end of the puerperium (6 weeks after delivery).

Antepartum haemorrhage (APH)

APH affects 3–5% of pregnancies. Placental abruption and placenta praevia are the most important causes of APH but are not the commonest. The majority of APH remains unexplained after clinical and ultrasound examination.

Causes

Antepartum haemorrhage is classified according to the source of the bleeding.

Local

There may be bleeding from the vulva, vagina or cervix. Bleeding from the cervix is not uncommon in pregnancy and may follow sexual intercourse. A cervical ectropion or benign polyp is often found, and only very rarely is there cervical carcinoma. Later in pregnancy, the passing of a blood-stained ‘show’, mucus along with a small amount of blood, may simply herald the onset of labour as the cervix becomes effaced.

Placental

Placenta praevia

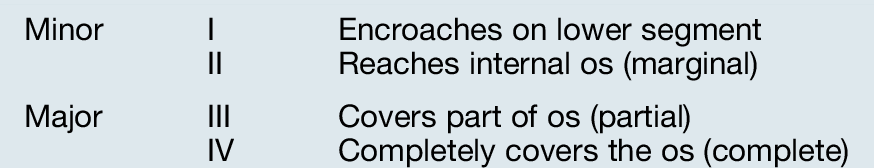

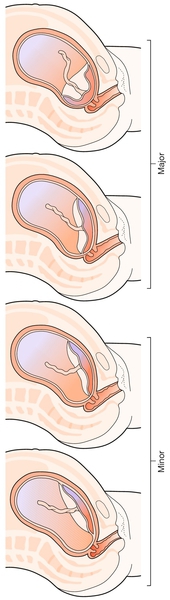

This is when the placenta encroaches upon the lower segment, with the lower segment arbitrarily defined on ultrasound scanning as extending 5 cm from the internal os. Placenta praevia is more common among women with a previous caesarean section but the majority of women with placenta praevia have no discernible risk factors. Transvaginal ultrasound is a reliable and safe method of determining the distance between the edge of the placenta and the internal os of the cervix. Placenta praevia is classified either as major or minor, or graded I–IV (Table 34.1, Fig. 34.1).

It is also important to note whether the placenta is anterior or posterior, as caesarean section is technically more difficult with an anterior placenta.

It is not possible to avoid haemorrhage in labour with a major placenta praevia, but it may be possible to deliver successfully with a minor degree of praevia. In the assessment of suitability for such a delivery, engagement of the presenting part is important together with the actual distance of the placenta from the internal os determined by ultrasound (Fig. 34.2). Those who do not have an at least partially engaged head should be delivered by caesarean section and a distance of at least 2 cm from placental edge to internal os is recommended before recommending vaginal birth. A low-lying placenta may be identified in an asymptomatic woman at the time of an ultrasound scan early in pregnancy and placental location is routinely determined at the time of the fetal anomaly scan at 20 weeks. As the uterus grows from the lower segment upwards, the placenta appears to move upwards with advancing gestation. In total, 2% of those with a low-lying placenta before 24 weeks; 5% of those at 24–29 weeks and 23% of those at 30 + weeks, will still have a placenta praevia at term. This is not a reflection of placental migration, but simply a feature of uterine growth. When a low-lying placenta is detected on ultrasound scanning early in pregnancy, it is necessary to repeat the scan early in the third trimester and then review the management if the placenta is still low.

The risk of placenta praevia is of a sudden, unpredictable, major haemorrhage and some clinicians advocate hospital admission from 30–32 weeks onwards, so that facilities for resuscitation and delivery are immediately available. This can be socially difficult for the woman, particularly if she has children at home, and immobility in hospital may predispose to thromboembolic disease. Outpatient management is frequently undertaken, particularly for those who have had no bleeding (placenta praevia an incidental ultrasound finding) or just light bleeding, and who live close to the hospital with good social support and available transport. Elective delivery is usually planned for 38–39 weeks, but will be earlier if there is a major haemorrhage.

Caesarean section in the presence of placenta praevia should be directly supervised or performed by a senior obstetrician, since a large blood loss is frequently encountered due to the relatively poor capacity of the lower segment of the uterus to contract.

Anterior placenta praevia in the presence of a history of one or more caesarean sections predisposes the woman to placenta accreta, where the placenta invades the myometrium and cannot be readily separated from the uterus following delivery. Placenta accreta can be diagnosed with ultrasound antenatally and MRI is increasingly being used to improve accuracy of diagnosis. The presence of placenta accreta markedly increases the chance of severe haemorrhage and a multidisciplinary approach to delivery is recommended. Severe haemorrhage can require hysterectomy and women should be warned of this possibility prior to surgery.

Placental abruption

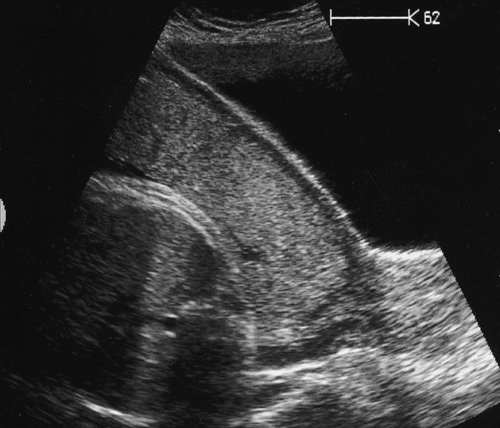

Placental abruption is defined as retroplacental haemorrhage (bleeding between the placenta and the uterus) and usually involves some degree of placental separation. Its management depends on the amount of bleeding, presence or absence of maternal haemodynamic compromise, the maturity of the fetus and its condition. Separation of the placenta results in a reduced area for gas exchange between the fetal and maternal circulations predisposing to fetal hypoxia and acidosis. It is crucial to remember that with placental abruption the amount of ‘revealed’ blood (bleeding from the vagina) may not reflect the total blood loss and, indeed, a woman may have considerable retroplacental bleeding without any external loss at all – a ‘concealed abruption’, the most hazardous type of abruption (Fig. 34.3).

History of a previous pregnancy affected by placental abruption and maternal cigarette smoking are among the risk factors for placental abruption, but the majority of placental abruptions occur by chance in women without identifiable risk factors.

Light bleeding from the edge of a normally situated placenta does not normally compromise the fetus and a brief episode of inpatient observation with subsequent surveillance of fetal growth with serial ultrasound fetal biometry is appropriate until delivery at term.

Major revealed haemorrhage is obvious, and urgent delivery is usually required. A major concealed abruption is inferred from the degree of pain, uterine tenderness and evidence of hypovolaemic shock; again, urgent delivery may be required. The decision between vaginal delivery and caesarean section is influenced by the degree of bleeding, maternal and fetal conditions.

If there is no fetal heartbeat, vaginal delivery is to be preferred, as the mother should not be subjected to an avoidable caesarean section when the baby is dead. However, in this situation it is likely that there will have been a major degree of blood loss. Hypovolaemic shock may develop and may progress to multisystem failure if not corrected. In addition, release of thromboplastins from the damaged placenta may lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with depletion of platelets, fibrinogen and other clotting factors. Waiting for vaginal delivery therefore carries risks, and caesarean section may occasionally be indicated to minimize these systemic maternal risks. Deciding on the appropriate mode of delivery is further complicated by the risks of carrying out an operation in the presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Less severe degrees of placental abruption can still be associated with fetal compromise. There is usually pain and frequent contractions, the contractions precipitated by irritation of the myometrium from the retroplacental clot. The fetal heart rate will show an abnormal pattern which will deteriorate to a fetal bradycardia before fetal death unless delivery is expedited. Placental abruption predisposes the mother to postpartum haemorrhage. The old adage ‘abruption kills the baby but the postpartum haemorrhage kills the mother’, fortunately, is experienced only rarely in modern obstetric practice but to remember it serves the obstetrician well.

Unexplained APH

A specific explanation for the APH is often not found, even after the pregnancy is over, and it is then presumed to have come from a normally situated placenta. Bleeding with no explanation is the commonest clinical scenario and, in the absence of maternal or fetal compromise, is managed expectantly. Unexplained APH, especially if more than one episode (recurrent unexplained APH), is a recognized risk factor for subsequent poor fetal growth.

Clinical presentations

Bleeding can be spotting, light, moderate or severe and can occur with or without pain. Admission to hospital is advised, as even light bleeding may be a warning of haemorrhage yet to come.

An attempt should be made to determine the cause of the bleeding. In practice, history and initial examination are carried out simultaneously. It is relevant to ask when the bleeding started, how much blood has been lost, and when the baby was last felt to move. Observation will tell if the mother is in pain, which suggests abruption or labour, and there may be visible blood on the bed, her legs or the floor. If the mother is pale, with low blood pressure and rapid pulse, there is probably hypovolaemic shock. With an abruption, the uterus is typically hard and tender (‘Couvelaire’ uterus, see History box) and there may be no discernible fetal heartbeat. There may be frequent contractions or continuous pain. When the bleeding is from a placenta praevia, the uterus is usually soft, the presenting part will usually be free, and the fetal heartbeat is usually present. Subsequent management depends on the estimated severity of haemorrhage.

Light bleeding, with a soft uterus and normal cardiotocography

An ultrasound scan should be arranged to check the placental site (if not already established by an earlier scan) and, providing the placenta is not low-lying, a speculum examination should be performed to look for cervical effacement or dilatation, an ectropion or a polyp. If all is normal, it is common practice to admit the woman at least until the bleeding settles. However, most clinicians will not admit the woman if the bleeding is light and clearly seen to be coming from an ectropion. Women who are rhesus-negative should be given prophylactic anti-D.

If there is a placenta praevia and the pregnancy is at more than 37–38 weeks’ gestation, it is reasonable to arrange for delivery by caesarean section. If less than this gestation, a conservative approach is usually appropriate.

Light bleeding, but with a hard, tender uterus

The diagnosis is probably a concealed abruption (with a small amount of revealed bleeding), and management revolves around maternal resuscitation, correction of hypovolaemia and coagulation defects, and evaluation of the fetal condition by cardiotocography. Prompt delivery is highly likely to be appropriate; the route of delivery will be influenced by a number of factors, including evidence of fetal compromise and the presence of maternal coagulopathy.

APH requiring maternal resuscitation

Whether the diagnosis is placenta praevia or an abruption, delivery is highly likely to be required, irrespective of gestational age.

Intrapartum haemorrhage

Abnormal bleeding during labour must be distinguished from a ‘show’ that may occur during cervical dilatation. In a previously low-risk pregnancy, intrapartum bleeding would be an indication for continuous electronic fetal monitoring.

Causes

Placental abruption

Placental abruption (see earlier) can occur during labour and should be particularly considered if the uterus does not relax between contractions.

Placenta praevia

As the cervix dilates, so the placenta separates from the uterine wall and typically painless bleeding occurs.

Uterine rupture

Uterine rupture is fortunately relatively rare, and is discussed on page 376.

Vasa praevia

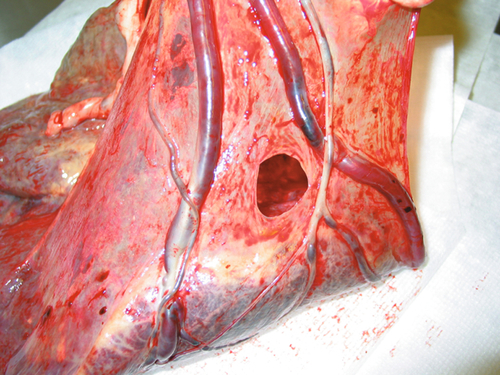

This is rare, and occurs when the umbilical cord vessels run in the fetal membranes and cross the internal os of the cervix. These vessels may rupture in early labour and this often leads to rapid fetal exsanguination. It may be that the cord is inserted into the membranes rather than directly into the placenta (type 1 vasa praevia, Fig. 34.4), or that the vessels are running from the placenta to a separate succenturiate placental lobe (type 2 vasa praevia). The condition presents as severe fetal distress or fetal death following a relatively small intrapartum haemorrhage. Diagnostic tests to differentiate fetal from maternal blood in APH are unreliable and baby is usually delivered urgently by caesarean section because of the fetal compromise. The diagnosis of vasa praevia is usually made retrospectively, by examination of the placenta and membranes. Although it is possible to diagnose the condition antenatally with colour flow Doppler ultrasound, routine screening for vasa praevia is not established practice.

Fig. 34.4Umbilical cord vessels running through the membranes.

If these vessels overlie the internal cervical os, it is termed ‘vasa praevia’.

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH)

It is impossible to predict with certainty which women will have a postpartum haemorrhage, and it is important to appreciate that a major haemorrhage can very rapidly lead to maternal death.

Definitions

There is always some bleeding during the third stage of a normal delivery, usually around 200–300 mL.

![]() A primary PPH is defined as a blood loss of 500 mL or more within 24 h of delivery.

A primary PPH is defined as a blood loss of 500 mL or more within 24 h of delivery.

![]() A secondary PPH is any significant loss between 24 h and 6 weeks after the birth.

A secondary PPH is any significant loss between 24 h and 6 weeks after the birth.

Primary PPH

This occurs in around 5% of all deliveries. It is more common in grand multiparity (four deliveries or more); women over age 35; with a BMI of over 35; multiple pregnancy; women with fibroids; polyhydramnios; placenta praevia and in those who have had a long labour. It may also follow an antepartum haemorrhage and is more likely in women with a past history of postpartum haemorrhage. Women with risk factors for PPH are advised to give birth in a consultant-led unit.

Prevention

It is important to treat anaemia in the antenatal period (haematinic supplements), particularly if the woman has risk factors for PPH. It is usual to give a uterotonic such as syntocinon 5 IU with delivery of the baby’s anterior shoulder; such active management of the third stage of labour is associated with a lower incidence of PPH.

Causes

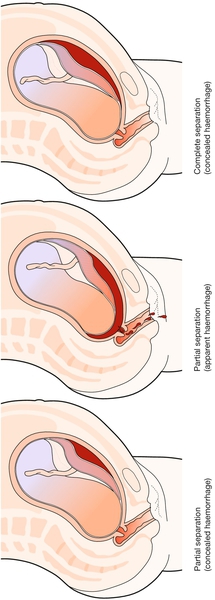

![]() Atony – including retained placenta (90%). Normally, contraction of the uterus in the third stage of labour causes compression of intramyometrial blood vessels, and bleeding stops promptly (Fig. 34.5). If there is uterine atony, this compression does not occur. Atony can occur following delivery of the entire placenta (the myometrium simply does not contract sufficiently well) or when part or all of the placenta is retained. The physical presence of placental tissue prevents effective uterine contraction and the partial placental separation results in bleeding from the placental bed.

Atony – including retained placenta (90%). Normally, contraction of the uterus in the third stage of labour causes compression of intramyometrial blood vessels, and bleeding stops promptly (Fig. 34.5). If there is uterine atony, this compression does not occur. Atony can occur following delivery of the entire placenta (the myometrium simply does not contract sufficiently well) or when part or all of the placenta is retained. The physical presence of placental tissue prevents effective uterine contraction and the partial placental separation results in bleeding from the placental bed.

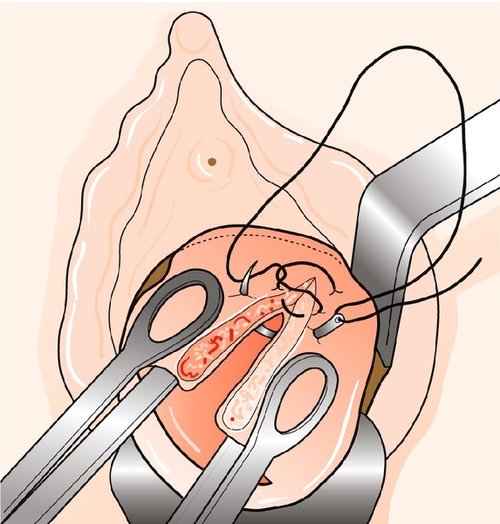

![]() Trauma (7%). Bleeding may be from an episiotomy, a vaginal tear, cervical laceration (Fig. 34.6) or a rupture in the uterine wall. Lacerations of the genital tract are more common after an instrumental delivery.

Trauma (7%). Bleeding may be from an episiotomy, a vaginal tear, cervical laceration (Fig. 34.6) or a rupture in the uterine wall. Lacerations of the genital tract are more common after an instrumental delivery.

![]() Coagulation problems – usually disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). DIC may be present due to a number of different causes including maternal sepsis and placental abruption.

Coagulation problems – usually disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). DIC may be present due to a number of different causes including maternal sepsis and placental abruption.

![]() Multiple causes may be present necessitating a systematic approach to the woman experiencing a primary PPH.

Multiple causes may be present necessitating a systematic approach to the woman experiencing a primary PPH.

Clinical presentation

The bleeding is usually obvious, but, occasionally, an atonic uterus can fill-up without obvious external loss and the first real sign can be cardiovascular collapse. A less dramatic, prolonged trickling of blood may go unnoticed, the significance of which may not be initially appreciated. With blood-soaked pads and bedding, it is common to underestimate the real loss. Signs of hypovolaemic shock must be sought.

The key questions are:

1. Has the placenta been delivered and is it complete?

2. Is the uterus firmly contracted?

3. If so, is the bleeding due to trauma?

Management

A controlled, reassuring presence is important. Ensure appropriate numbers, skill mix and expertise of staff are in attendance or are en route.

Assessment

![]() Make a rough but realistic estimate of the loss.

Make a rough but realistic estimate of the loss.

![]() Determine the pulse and blood pressure.

Determine the pulse and blood pressure.

![]() Palpate the abdomen to assess the size and tone of the uterus.

Palpate the abdomen to assess the size and tone of the uterus.

Treatment

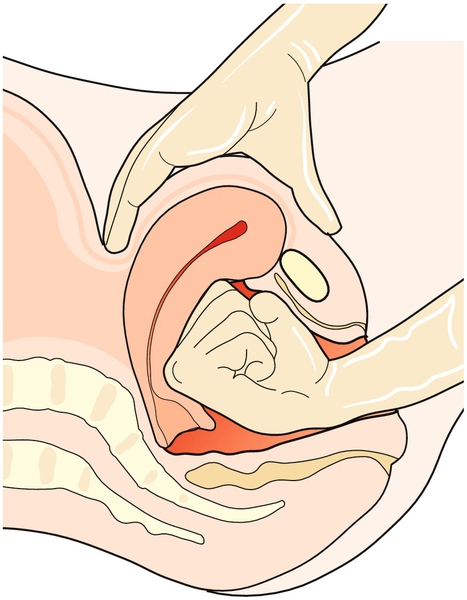

![]() If the uterus is atonic, a contraction can be ‘rubbed up’ by abdominal massage. Bimanual compression may also be performed (Fig. 34.7).

If the uterus is atonic, a contraction can be ‘rubbed up’ by abdominal massage. Bimanual compression may also be performed (Fig. 34.7).

![]() Intravenous access should be established with two wide-bore cannulae and blood taken for haemoglobin concentration, platelet count, blood clotting and a red cell cross-match (the number of units depends on volume lost).

Intravenous access should be established with two wide-bore cannulae and blood taken for haemoglobin concentration, platelet count, blood clotting and a red cell cross-match (the number of units depends on volume lost).

![]() An intravenous bolus of syntocinon 10 IU should be given to contract the uterus, followed by a syntocinon infusion.

An intravenous bolus of syntocinon 10 IU should be given to contract the uterus, followed by a syntocinon infusion.

![]() Crystalloid and/or colloid should be rapidly infused to maintain the circulating volume. A urinary catheter should be inserted to measure urine output and avoid a full bladder becoming an obstacle to uterine contraction.

Crystalloid and/or colloid should be rapidly infused to maintain the circulating volume. A urinary catheter should be inserted to measure urine output and avoid a full bladder becoming an obstacle to uterine contraction.

![]() If the placenta has not been delivered, a gentle attempt at umbilical cord traction should be tried. If still retained, a regional block or general anaesthetic will be required for a manual removal of the placenta. If the placenta is abnormally adherent (placenta accreta) in the presence of haemorrhage, an emergency hysterectomy may be required.

If the placenta has not been delivered, a gentle attempt at umbilical cord traction should be tried. If still retained, a regional block or general anaesthetic will be required for a manual removal of the placenta. If the placenta is abnormally adherent (placenta accreta) in the presence of haemorrhage, an emergency hysterectomy may be required.

![]() Further oxytocics can be given, e.g. further boluses of intravenous syntocinon, intramuscular ergometrine, intramuscular carboprost and/or rectal misoprostol (carboprost and misoprostol are synthetic prostaglandin analogues).

Further oxytocics can be given, e.g. further boluses of intravenous syntocinon, intramuscular ergometrine, intramuscular carboprost and/or rectal misoprostol (carboprost and misoprostol are synthetic prostaglandin analogues).

![]() Bleeding from genital tract lacerations should be diagnosed promptly by examination (often under regional block or general anaesthesia) and bleeding arrested by application of clamps and suturing.

Bleeding from genital tract lacerations should be diagnosed promptly by examination (often under regional block or general anaesthesia) and bleeding arrested by application of clamps and suturing.

If the haemorrhage continues:

![]() a central venous pressure (CVP) line should be considered and inserted by the anaesthetist, and a blood transfusion commenced. Group-specific un-cross-matched blood or even O negative blood may be used in extreme emergency

a central venous pressure (CVP) line should be considered and inserted by the anaesthetist, and a blood transfusion commenced. Group-specific un-cross-matched blood or even O negative blood may be used in extreme emergency

![]() the coagulation defects of DIC should be corrected with fresh frozen plasma or cryoprecipitate, depending on advice obtained by the duty haematologist. Rarely, recombinant factor Vlla is appropriate

the coagulation defects of DIC should be corrected with fresh frozen plasma or cryoprecipitate, depending on advice obtained by the duty haematologist. Rarely, recombinant factor Vlla is appropriate

![]() additional techniques to stop haemorrhage due to atony are aimed at either maintaining compression of the uterus or applying pressure directly to the placental bed. A ‘brace’ suture involves an additional laparotomy (unless the haemorrhage is following a caesarean section) and the placing and tying of sutures around the uterine body in order to maintain compression. Placement of an intrauterine balloon does not require a laparotomy and works by applying pressure directly to the placental bed. Hysterectomy may be indicated, especially if there is a placenta accreta. Internal iliac artery ligation is occasionally performed (Fig. 34.8)

additional techniques to stop haemorrhage due to atony are aimed at either maintaining compression of the uterus or applying pressure directly to the placental bed. A ‘brace’ suture involves an additional laparotomy (unless the haemorrhage is following a caesarean section) and the placing and tying of sutures around the uterine body in order to maintain compression. Placement of an intrauterine balloon does not require a laparotomy and works by applying pressure directly to the placental bed. Hysterectomy may be indicated, especially if there is a placenta accreta. Internal iliac artery ligation is occasionally performed (Fig. 34.8)

![]() radiologically directed arterial embolization is also an option in the management of PPH provided the woman is stable for transfer to the radiology theatre suite. This procedure is highly specialized and is performed by interventional radiologists. Embolization often enables haemorrhage to be controlled without resorting to hysterectomy.

radiologically directed arterial embolization is also an option in the management of PPH provided the woman is stable for transfer to the radiology theatre suite. This procedure is highly specialized and is performed by interventional radiologists. Embolization often enables haemorrhage to be controlled without resorting to hysterectomy.

Secondary PPH

This is usually due to infection of the uterine cavity, retained products of conception or both; exceptionally, it is due to trophoblastic disease. Pulse rate, blood pressure and temperature must be measured and the uterus palpated for tenderness. Endocervical and vaginal swabs are sent for culture.

In practice, the decision is usually between conservative management with antibiotics, or arranging for an evacuation of retained products under regional or general anaesthesia. In the first week, the evacuation can often be carried out digitally without the need to instrument the uterus. Clinical judgement is important, often giving broad-spectrum antibiotics in the first instance if the bleeding is not severe, and arranging an evacuation if the bleeding does not settle. Ultrasound scans of the postpartum uterus are often difficult to usefully interpret. However, in the presence of persistent bleeding, ultrasound can be used to observe the spontaneous resolution of intrauterine haematomas and identify retained products.