Observation Medicine and Clinical Decision Units

Principles of Observation Medicine

Observation services are an extension of emergency department (ED) services specifically designed to address unmet patient needs. Observation services improve patient care by continuing the evaluation and management of selected ED patients who would otherwise require admission for acute care services. Approximately 80% of patients treated on observation services can be sent home without the need for hospitalization. The cost to evaluate and to treat these patients is half that incurred by admission.1,2 In addition, the physician threshold for extended evaluation (traditionally provided with hospitalization) is lowered. Patients with atypical signs and symptoms are more fully evaluated to rule out serious conditions, such as acute myocardial infarction or acute appendicitis. Thus in addition to lower costs, there is also a simultaneous decrease in the inadvertent release home of patients with serious disease.1

Two categories of patients benefit from extension of the usual 2- to 4-hour ED visit to up to 24 hours. One group is selected patients with a critical diagnostic syndrome (Box 195-1). These are patients whose diagnoses are unclear after the initial ED evaluation and who will benefit from further evaluation during observation. They are either admitted if they are found to have a serious disease or released home. The second group is patients with selected emergency conditions (see Box 195-1). Those patients not successfully treated during the traditional ED treatment period benefit from further treatment in an observation unit.

Observational Approach

Additional physician staffing is also required for the observation unit. Management of ED patients in the observation unit for an additional 12 to 14 hours requires approximately a doubling of the physician service for a single patient.3 Calculations of the physician staffing for the amount of additional services will be approximately one full-time equivalent for every 2000 patients observed per year. As with the nurses, physicians in the observation unit must have broad-based knowledge and experience in the management of a wide variety of disease processes. Emergency physicians possess the skill sets necessary for observation medicine. The emergency physician is ultimately responsible for the care of the patient and needs to provide clear leadership at all times.

The structure of the observation unit will determine its clinical effectiveness and financial viability. Models for the structure of the observation unit are reviewed in the American College of Emergency Physicians textbook Emergency Department Design.4 An observation unit that is properly designed and located adjacent to the ED will result in a 50% lowered cost compared with traditional hospital admission while providing equivalent or improved quality of patient care.

Clinical Conditions

Evaluation of Critical Diagnostic Syndromes

Abdominal Pain

Traditional Approach.: Abdominal pain is one of the most frequent complaints in the ED and accounts for 4 to 8% of all visits.5 The typical ED evaluation of the patient with abdominal pain includes a thorough history and physical examination and the appropriate diagnostic tests. Within the short time frame of 2 to 4 hours, patients are given a provisional diagnosis and are either hospitalized or sent home.

Problem with Traditional Approach.: The ED evaluation is inadequate for many patients, and in 40% of patients the origin of abdominal pain is never determined. Acute appendicitis is the most common abdominal surgical emergency and illustrates the inadequacies of the traditional approach. The diagnosis of acute appendicitis is missed in 20 to 30% of cases (false-negative decisions). In addition, 20 to 30% of patients taken to surgery for acute appendicitis are found to have no abnormality (false-positive decisions).5 Whereas abdominal computed tomography (CT) imaging has been found to improve physician performance in identifying patients with acute appendicitis,6–8 there is increasing concern for the amount of ionizing radiation exposure to patients from the increased use of CT.9

Observational Approach.: With observation, the ED evaluation can be extended from 2 to 4 hours to up to 23 hours for selected patients (Box 195-2). After the initial history and physical examination of the patient, the physician estimates the probability that the patient has appendicitis by use of validated risk stratification tools, such as the Alvarado score. Those patients deemed to have a low probability of disease are ideal candidates for the observational approach.10 Patients who are at greater risk of having their diagnosis missed, such as those who are immunocompromised, pregnant, or at the extremes of age, often benefit from observation. Elders in particular benefit from observation; surgical problems are often missed because of the atypical clinical findings that occur with older age.11

During the period of observation, the patient is usually kept fasted and hydrated intravenously. Serial abdominal examinations are repeated at 4-hour intervals, and laboratory tests such as complete blood count and C-reactive protein level are repeated as appropriate. Imaging and consultations are also arranged during this time frame. Patients without appendicitis will experience improvement of their pain and have had completion of diagnostic workup and exclusion of surgical disease.12 Patients are hospitalized if they have no improvement, worsening of their clinical findings, or surgical disease diagnosed by testing. In patients who do have appendicitis, signs and symptoms will continue or worsen.13

Physician decision-making improves with observation, and false-positive surgeries can nearly be eliminated. Intensive observation with serial physical examinations at least every 8 hours rather than once per day has been found to reduce the false-positive rate from 20 to 5%.13,14 The use of a period of observation can also help identify many patients whose diagnoses otherwise would be missed during the initial ED evaluation. Initially, many appendicitis patients have few clinical signs or symptoms of appendicitis on presentation, making diagnosis difficult.12 Physicians delaying disposition decisions in questionable cases can avoid these false-negative decisions. Appendicitis patients have more signs and symptoms during short-term observation, whereas those without the disorder clear their signs and symptoms. Thus fewer patients have an unclear clinical picture after observation with fewer false-negative decisions.15 Missing of the diagnosis at the initial evaluation delays surgery up to 72 hours and doubles complications (perforation, abscess).11 Physicians who observe selected patients with low probability of disease rather than discharge them after their initial evaluation can avoid most of these missed diagnoses and the resulting complications.

Chest Pain

Traditional Approach.: The ED evaluation of chest pain is composed of two assessments: (1) the probability that the patient has an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or acute coronary ischemia (ACI) and (2) the risk of the patient’s having a life-threatening event. These two factors determine the appropriate setting for further testing and monitoring. The probability of AMI is traditionally assessed in the ED with a directed history, physical examination, and electrocardiogram (ECG) and an initial measurement of cardiac biomarkers, such as creatine kinase MB fraction (CK-MB), cardiac troponin I or T, B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), and myoglobin. Other markers, such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, myeloperoxidase, and D-dimer, are used less frequently.1–5,7,8,16–23

Problem with Traditional Approach.: The poor performance of initial diagnostic testing makes the evaluation of chest pain highly dependent on clinical judgment. The initial ECG is diagnostic in only 50% of AMI patients,24 and the initial CK-MB measurement has a sensitivity of only 35%.25 Reliance on physician judgment and initial ED testing has resulted in as many as 2 to 5% of AMI patients being discharged home with inadvertent reassurance.1,26 AMI patients not identified at the initial evaluation and released from the ED have up to a 25% risk of poor outcome.1 Fear of inadvertently releasing AMI patients has led many emergency physicians to err on the side of admitting a large number of patients who do not have AMI or unstable angina. As a result of the increased sensitivity of a more liberal admission policy, two thirds of patients admitted for chest pain have a noncardiac cause of their symptoms.1 Costs range in the billions of dollars for these negative evaluation hospitalizations.4 Despite this liberal admission policy, missed AMI remains one of the leading causes of malpractice suits against emergency physicians.27

Observational Approach.: The emergency physician can use the observation unit to extend the evaluation of selected patients with chest pain (Box 195-3). When it is used principally for such a purpose, the observation unit has been termed a chest pain unit. The chest pain unit has been successful in improving the sensitivity and specificity of the evaluation process.28,29 Patients with low risk of AMI are transferred to the observation unit. Patients unsuitable for observation unit evaluation include those who have a high to moderate probability of acute myocardial ischemia, unstable vital signs, electrocardiographic findings of AMI, or persistent or recurring chest pain consistent with unstable angina.

The physician identifies patients with low probability for ACI by use of one or more risk stratification tools. Risk stratification based on classic risk factors alone has been shown to be a poor predictor of short-term outcome.30 Risk stratification based on electrocardiographic findings is more reliable. The Brush ECG criteria classify as low risk those without ST segment elevation or depression, T wave inversion or strain, new (or presumed new) Q waves, left bundle branch block, or paced rhythm.31 Another useful risk stratification tool is the Goldman protocol, which uses history, physical examination, and electrocardiographic findings to classify patients into high (>70%), moderate, or low (>7%) risk.32 Another tool is the acute cardiac ischemia time-insensitive predictive instrument, which uses age and gender of the patient, presence or absence of chest pain, and electrocardiographic findings to assign a probability of acute ischemia.33

Patients admitted to the observation unit are first evaluated to rule out a myocardial infarction. They are serially tested with cardiac markers and ECGs. CK-MB estimation at 0, 3, and 6 hours after presentation has 100% sensitivity, 98% specificity, and 100% negative predictive value in the detection of AMI.28,29 Other useful serum cardiac markers are the troponins (I and T) and myoglobin. Patients who present more than 24 hours after symptom onset have negative CK-MB and myoglobin testing findings, but troponin T or I remains positive for up to 6 days. Patients are monitored with continuous ECG monitors equipped with dysrhythmia alarms and memory storage capabilities. Continuous electrocardiographic ST segment monitoring can detect dynamic ST segment changes indicative of ischemia, which, when present, indicate an increased likelihood for an adverse cardiac event.34 Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring also helps detect arrhythmias that may be associated with acute coronary syndrome.

After evaluation to exclude AMI, the patient is evaluated for possible acute coronary syndrome. This may be performed before release of the patient from the observation unit or at follow-up evaluation within 72 hours of discharge. The most common testing modality used is exercise stress testing.35 Patients who obtain their target heart rate without electrocardiographic evidence of ischemia can be released home. They have an annual mortality rate of less than 1%.35 The performance of exercise testing depends on the ability of the patient to exercise adequately, gender (women have higher false-positive rates), interpretability of the resting ECG, and availability of the test. Other testing modalities include stress echocardiography, technetium (99mTc) sestamibi scanning, and cardiac CT angiography.

Approximately one third of ED patients with chest pain are candidates for observation, with 80 to 85% released home after observation.1 This reduces the hospitalization rate from 60 to 70% down to 40 to 50%.1 The cost of evaluation with observation is half that of traditional evaluation with hospitalization.1 The safety and cost-effectiveness of the observation approach have been confirmed in four randomized clinical trials.36–39 Payers expect clinicians to be cost-effective and to use observation for evaluation of patients with chest pain when it is appropriate. The Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services began audits in 2010 by Recovery Audit Contractors to deny payment for patients with low probability of AMI chest pain who were admitted to the hospital rather than evaluated in the lower cost outpatient observation unit. The use of observation units for chest pain evaluation is thus becoming the standard in U.S. hospitals.

Deep Venous Thrombosis

Traditional Approach.: The primary objectives for the treatment of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) are to prevent pulmonary embolism, to reduce morbidity, and to prevent or to minimize the risk for development of postphlebitic syndrome. Patients with suspected DVT are usually hospitalized when diagnostic testing is unavailable in the ED or the diagnosis has been confirmed and further management is required. Traditionally, anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin has been administered by continuous intravenous infusion for 5 to 7 days while oral anticoagulation is instituted.40 Meta-analyses of randomized trials of unfractionated heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) showed that they were similar, with a risk of recurrent DVT of 4%, a risk of pulmonary embolism of 2%, and a risk of major bleeding of 3%.41,42 The anticoagulant response to this treatment varies markedly among patients, and therefore the dosage must be monitored by coagulation profiles.43

Problem with Traditional Approach.: New modalities for investigation and treatment have made it possible to manage DVT on an outpatient basis with lower costs than with hospitalization. There are new, less invasive investigative tests and newer therapeutic agents that do not require monitoring of coagulation profiles.

Observational Approach.: The role of the observation unit in the management of patients thought to have DVT is for diagnostic testing as well as for initiation of therapy with LMWH and patient education. Patients often present during the night or on weekends when definitive tests for DVT (e.g., Doppler ultrasonography) are not available. The patient may have a positive D-dimer test finding, which requires a confirmatory definitive test because of its poor specificity.44 In these circumstances, the patient can be anticoagulated for the short term with one dose of LMWH (enoxaparin, 1 mg/kg twice daily) until the diagnosis can be clarified. If the diagnosis is confirmed, the patient can be admitted or treated as an outpatient on the basis of hospital protocol. Patients considered for outpatient management are instructed in how to administer the medication. They are educated about DVT and its complications and the possible side effects of the LMWH. Appropriate follow-up evaluation is also arranged before discharge. With this approach, patients spend 67% less time in the hospital and have greater physical activity and social functioning than their standard heparin cohorts do.45 Outpatient management is not recommended if the patient has proven or suspected concomitant pulmonary embolism, significant comorbidities, extensive iliofemoral DVT, active bleeding, renal failure, or poor follow-up compliance. LMWH is administered by subcutaneous injection in doses adjusted for the patient’s weight, without laboratory monitoring.

Outpatient testing with venous compression ultrasonography has become readily available.46 It is both sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of proximal (femoropopliteal) DVT.47 When repeated compression ultrasonography is compared with impedance plethysmography, compression ultrasonography is superior in detection of DVT.46 It has been proved to be a safe method of deciding when to administer anticoagulation.44 The D-dimer assay has also been shown to be a useful adjunct to compression ultrasonography in outpatient testing.

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Traditional Approach.: Most patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding are admitted to the hospital after initial ED assessment and stabilization.

Problem with Traditional Approach.: Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is a common and potentially life-threatening condition with an overall mortality rate of 6 to 10%.48 However, most cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding are self-limited, and 80% of patients have only one bleeding episode.49

Observational Approach.: Not all patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding do poorly, suggesting that outpatient management is possible if patients at high risk for further bleeding can be identified. Prognostic indicators include the patient’s age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, orthostatic changes in blood pressure or pulse, color of stool or emesis, anticoagulant use, and comorbid conditions.50 In an attempt to refine diagnostic accuracy, risk assessment, and disposition, several scoring systems have been developed. Some practitioners use hemodynamic stability, intensity of bleeding, and underlying health status as predictors of rebleeding, need for surgery, and mortality.51 Some use a period of observation with early endoscopy to identify the patient who can be discharged early. Patients found to have clean-based ulcers at endoscopy have a rebleeding rate of less than 2% and virtually never require urgent intervention for recurrent bleeding and can be released. Use of this approach has been proved to be both safe and cost-effective; a prospective clinical trial demonstrated that 24% of patients can avoid hospitalization, with cost savings of $990 per patient.52

Syncope

Traditional Approach.: Syncope is caused by a spectrum of disease entities. ED evaluation includes a thorough history, physical examination, and 12-lead ECG. Patients with evidence of possible myocardial ischemia or a cardiac cause of their syncope are usually admitted to the hospital because cardiac syncope has a high risk of death (up to one third will have a poor outcome).53 Those with concomitant heart failure have a 25% mortality rate at 30 days.54 On the other hand, patients with noncardiac syncope have a low risk of adverse events (1%) and can be managed as outpatients.53

Problem with Traditional Approach.: Attempts to exclude a possible cardiac cause of syncope usually result in 25 to 40% of patients being hospitalized for further evaluation and management.54 The traditional ED evaluation identifies only 50% of patients with a serious cause of their syncope,55 and this has often resulted in a liberal admission policy; however, one study found that only 12% of patients had a serious cause of syncope that justified hospitalization.56 It is estimated that a third of patients admitted after their ED evaluation have very low risk of an adverse event (<2%) and would be appropriate for outpatient observation evaluation.57

Observational Approach.: The use of observation for selected patients with syncope reduces unnecessary hospitalizations (Box 195-4). Patients with a cardiac syncope have a poor prognosis and need to be identified. These patients often do not have chest pain as a symptom, but they may have ischemic changes on the ECG, arm or shoulder pain, or prior history of exercise-induced angina. A “rule out myocardial infarction” evaluation with cardiac monitoring, serial ECGs, and enzyme measurement may be the only way to identify these patients. Prolonged electrocardiographic monitoring can point to a specific cause in up to one fifth of patients, with half of all abnormalities detected in the first 24 hours.58

The challenge for the emergency physician is to risk stratify patients into very low risk, who can be discharged home; low risk, who are appropriate for outpatient observation; and moderate to high risk, who are appropriate for acute care hospitalization. Many factors have been found to correlate with adverse outcomes and should be considered by the clinician in the risk stratification, but attempts to create simple high-reliability decision rules have not been successful.59 Martin found that the 1-year risk of dysrhythmia or death in syncope patients correlates with four factors: an abnormal ECG, history of ventricular dysrhythmia, history of heart failure, and age older than 45 years.59 Patients with none of these risk factors have only a 4.4% rate of adverse events at 1 year and may be appropriate for outpatient evaluation. In contrast, patients with three or four risk factors have a 58% adverse outcome rate and should be hospitalized. Patients with one or two risk factors have intermediate risk and may be appropriate for evaluation on an observation service. The San Francisco Syncope Rule has been found to have sensitivity in identifying patients who are at immediate risk for serious outcomes within 7 days that ranges in different studies from 74 to 96%.60,61 Its criteria are abnormal electrocardiographic findings, history of congestive heart failure (CHF), dyspnea, hematocrit level of less than 30%, and hypotension.60,61 The Risk stratification Of Syncope in the Emergency department (ROSE) criteria suggest that an elevated BNP level, Hemoccult-positive stool, anemia, low oxygen saturation, and presence of Q waves on the ECG predict serious outcomes at 30 days.62 These rules had a sensitivity of 87% and a negative predictive value of 98.5% to help risk stratify patients. In this study, the isolated finding of a BNP level above 300 pg/mL was a major predictor of serious outcomes and was present in 89% of patients who died within 30 days. Another study found that 6.1% of patients had severe outcomes within 10 days of syncope evaluation.63 The mortality rate was 0.7%, and 5.4% of patients were readmitted or experienced major therapeutic intervention. Risk factors associated with severe short-term outcomes included abnormal ECG, history of CHF, age older than 65 years, male gender, history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, structural heart disease, presence of trauma, and lack of prodromal symptoms. The Evaluation of Guidelines in SYncope Study 2 (EGSYS 2) prospectively observed nearly 400 patients at 1 month and 2 years. The death rate was 2% at 1 month and 9% at 2 years. Patients with advancing age, presence of structural heart disease, or abnormal ECG had higher risk.64 Osservatorio Epidemiologico sulla Sincope nel Lazio (OESIL) score is another clinical decision rule that has been found to have limited accuracy.65,66 Additional factors indicating that a patient should be admitted rather than placed in outpatient observation are abnormal neurologic findings, positive cardiac biomarkers, and loss of consciousness for longer than 15 minutes.

Because many factors should be considered in the risk stratification for patient disposition to observation or hospitalization (see Box 195-4), the best practice approach is to develop an institutional consensus on this risk stratification and to codify it in a syncope order set. This approach reduces physician variability in decision-making by more uniformly adopting evidence-based practices, which improves both quality of patient care and use of health care resources.

During the observation period, serial examination of patients is carried out, including vital signs, with the majority of patients safely discharged home without hospitalization.67 Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring, consultation, serial cardiac enzyme determinations, and further tests, such as two-dimensional echography of the heart, psychiatric assessment, and tilt table testing, should be arranged when appropriate. Tilt table testing is a useful investigation in patients with recurrent syncope when heart disease is not suspected. Up to 60% of patients who have vagally mediated syncope can be detected by this modality.68 The period of observation can also identify patients with cardiac dysrhythmias or sinus pauses who are candidates for more extensive diagnostic evaluation in the hospital.

Transient Ischemic Attack

Traditional Approach.: More than 300,000 people suffer a transient ischemic attack (TIA) each year.69 For most patients, it is a transient event that will not recur if they take an aspirin each day. However, for 10% of patients, it is a warning sign that they will suffer a stroke unless they are appropriately evaluated and treated.70 Traditionally, the patient is assessed in the ED with history, physical examination, laboratory tests, electrocardiography, and head CT scan. Most patients are then hospitalized for serial clinical evaluations, neurology consultation, carotid Doppler testing, echocardiography, and cardiac monitoring.67

Problem with Traditional Approach.: The problem with the traditional approach is that most TIA patients are admitted to the hospital. After 3 days of evaluation, few will be found to have carotid or heart disease requiring an intervention.

Observational Approach.: Observation is an alternative to hospitalization for TIA patients with a normal ED evaluation for whom the emergency physician still has concern. An accelerated diagnostic observation protocol was compared with acute care hospitalization in a prospective randomized clinical trial. All patients had full evaluation in the observation unit or inpatient ward with serial clinical examinations, neurology consultation, carotid duplex ultrasonography, echocardiography, and cardiac monitoring.71,72 Clinical outcomes were equivalent with the two approaches, but the observation unit was more efficient (length of stay, 25 hours vs. 61 hours) and had lower costs ($890 vs. $1547).71,72

Trauma

There are more than 30 million trauma-related ED visits annually.73 Patients with serious injuries require hospitalization for definitive therapy, whereas those with minor injuries can be discharged home after treatment. The problem with the traditional ED approach is that many patients have injury patterns or actual injuries that fall somewhere between these two scenarios. If these patients are released, there is a risk that some will have poor outcomes as a result of missed injuries. On the other hand, because the majority of these patients do not have serious injuries, admitting this group to the hospital will result in a waste of scarce health care resources.

Observation units have been found to be an efficient and useful strategy in the evaluation and management of trauma victims.74 With observation, selected patients can be evaluated further to determine the need for admission. One study of 20,000 patients treated in an ED observation unit during a 12-month period found that 3% of patients were admitted to the observation unit, with 86% safely discharged home without the need for admission.74

Blunt Abdominal Injury

Traditional Approach.: Current ED management of blunt abdominal trauma (BAT) includes history, physical examination, blood analysis, plain radiography, ultrasonography, and CT scan. After initial stabilization and exclusion of other major injuries in the ED, most patients suffering BAT are admitted to the hospital for further evaluation and monitoring.

Problem with Traditional Approach.: The initial evaluation is inadequate for accurate disposition of many BAT patients. One third of patients who do not have any symptoms or signs suggestive of intra-abdominal injury may actually have significant injury.75 Also, because none of the present modalities for investigation of the presence of injury is 100% sensitive, many patients with initially normal investigations are hospitalized.

Observational Approach.: BAT patients appropriate for observation include those who, after initial evaluation, have no clear evidence of serious injury on physical examination but remain at risk for serious injury because of the mechanism of the injury or the individual’s personal health (e.g., advanced age or use of anticoagulants). Evaluations during observation for up to 23 hours include repeated physical examinations, laboratory testing, imaging, and specialty consultations. Patients are hospitalized if their condition deteriorates during the observation period or if, after testing, they are found to have serious internal injury. Patients with normal findings on evaluation and the ability to tolerate feeding can be safely released home. Patients who have sustained significant BAT by mechanism of injury or have equivocal findings on abdominal examination should undergo further testing, such as CT scan, for detection of occult injury.76 Ultrasonography (focused assessment with sonography for trauma [FAST]) is being increasingly used in the initial evaluation of the patient with BAT because it is a rapid noninvasive study with 99% specificity for detection of abdominal injury.77 However, it cannot be used to rule out serious intra-abdominal injury because a meta-analysis of 62 trials found the overall sensitivity of FAST to be only 79%.77 CT alone is not adequate to rule out serious injury, with sensitivity of only 80 to 95%.78 Short-term observation alone in patients with BAT is not sufficient because up to 20% of patients with significant injury will not have abdominal tenderness or develop it even after a short period of observation.78 Thus the prudent approach to patients with significant BAT without clear evidence of intra-abdominal injury is the use of a diagnostic test, such as CT, together with a period of observation.

Penetrating Abdominal Injury

Traditional Approach.: Most patients with penetrating abdominal injury are hospitalized for further evaluation, which may include wound exploration in the operating room and additional diagnostic testing.

Problem with Traditional Approach.: Many of these hospitalizations are unnecessary because only two thirds of patients with abdominal stab wounds have a breach of the peritoneum, and two thirds of these do not sustain visceral injury.79

Observational Approach.: A period of observation can identify those patients who do not require surgical intervention. Patients undergo serial examinations by the physician, further diagnostic testing, and specialty consultation. Those without evidence of peritoneal perforation or visceral injury after evaluation are sent home after proper wound care.

The conservative approach to penetrating abdominal wounds was developed in the 1970s. Those without peritoneal breach can be safely sent home after wound care and a period of observation without the need for hospitalization. Those with stab wounds to the abdomen with peritoneal breach but a negative finding on diagnostic laparoscopy or imaging with CT scan or ultrasonography can be safely managed in an observation unit.79–82 Patients with significant intra-abdominal injuries identified during observation are admitted; the 70 to 90% of patients without such injuries are released home.80,83 Gunshot wounds are often more difficult to evaluate than stab wounds. However, patients who appear to have tangential gunshot wounds can avoid surgery with observation if they are hemodynamically stable and have initial negative test findings. Penetrating wounds are manifested differently in children than in adults.84 Initial diagnostic testing with CT and diagnostic peritoneal lavage in children detects only 50% of injuries, with only 30% of patients having localized tenderness. Observation can help avoid unnecessary surgery in patients without injury and missing of the diagnosis in those without clear evidence of injury.

Blunt Chest Trauma

Traditional Approach.: Many patients who have a history of blunt chest trauma (BCT) in high-velocity accidents are admitted to the hospital to rule out myocardial or pulmonary contusion.

Problem with Traditional Approach.: Very few patients admitted to the hospital with BCT from high-velocity accidents without initial evidence of injury are found to have serious injury during hospital evaluation.85

Observational Approach.: Patients with isolated BCT who are otherwise stable with a normal ECG are suitable for a period of observation to exclude myocardial injury. During the period of observation, patients are monitored with continuous electrocardiography, specifically assessing for dysrhythmias. Serial enzyme determinations, such as troponin level, are also carried out to detect evidence of myocardial injury. Those patients with sternal fractures or other evidence of higher risk of intrathoracic injury should be considered for transesophageal echocardiography.86 Those with normal evaluations during the period of observation are released home for outpatient follow-up.

Much of the period of observation in patients with BCT focuses on identification of the presence and prognosis of myocardial contusions. The overall incidence of cardiac-related complications in these patients is low (0.1%).87 Patients with blunt cardiac trauma who have complications usually have an abnormal ECG or abnormal CK-MB or troponin level at presentation. Conversely, a normal ECG and CK-MB and troponin levels correlate with the lack of clinically significant complications.88,89 Patients who have isolated chest wall contusions and no abnormality of serial CK-MB or troponin values and no electrocardiographic abnormalities or dysrhythmia during 6 to 12 hours of electrocardiographic monitoring are unlikely to have complications.

Penetrating Chest Injury

Traditional Approach.: Patients with penetrating chest injury present with a spectrum of severity ranging from severe life-threatening injury requiring urgent operative intervention to hemodynamically stable patients with a normal initial evaluation. Most patients presenting with penetrating chest injuries are admitted to the hospital. Often, even those with a normal initial evaluation are admitted for exclusion of serious injury to the heart, lungs, and major blood vessels.

Problem with Traditional Approach.: The accuracy of this approach is limited because many patients with evidence of injury are admitted but have no further deterioration or need for medical therapy. On the other hand, there are those without obvious evidence of serious injury who will have a negative outcome if they are released after the initial evaluation.

Observational Approach.: A period of observation combined with diagnostic imaging can improve clinical decision-making. Patients with evidence of a small pneumothorax or hemothorax can be monitored for deterioration. Those without evidence of serious injury but of concern to the physician can likewise be observed for complications. During the period of observation, patients are monitored for respiratory or hemodynamic compromise. Repeated chest radiographs can detect the development of hemothorax or pneumothorax. Patients who deteriorate during the period of observation require hospitalization.

The safety and efficacy of managing asymptomatic stab wound victims in the short-term observation unit have been clearly established in multiple studies.90–92 A total of 5 to 15% will require hospitalization because of development of delayed pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, hematemesis, or pneumopericardium.90 In addition, the majority of stab wound victims with small pneumothoraces or hemothoraces will be treated solely with a chest tube without further surgical intervention. Major trauma centers can manage many of these patients as outpatients without hospitalization after a period of observation.

Patients with penetrating wounds to the cardiac area of the chest (between the nipples), the region of the great vessels, or the thoracoabdominal area usually require more intensive testing to exclude injury not only to the heart, major vessels, and lungs but also to the diaphragm and the abdominal organs. Echocardiography may detect pericardial fluid or tamponade in patients with penetrating injury close to the heart.93–95 Patients with small effusions may be observed in a monitored setting with serial examinations, whereas patients with large effusions should be treated surgically.95 Patients with normal findings on echocardiography can be observed in the observation unit. Even patients with small effusions may have sustained a serious injury, so the intensity of monitoring needs to be high.

Treatment of Emergency Conditions

Traditional Approach.: More than 20 million people in the United States are afflicted with asthma. Acute exacerbation of asthma is a common ED presentation, with estimated annual admissions exceeding 450,000.96 Traditionally, therapy is provided in the ED for 2 to 4 hours, consistent with national guidelines.97 Initial assessment includes history, physical examination, oxygen saturation, and peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) or forced expiratory volume in 1 minute. Treatment consists of beta-agonists, magnesium sulfate, and steroids, when appropriate. Patients who do not improve after 3 or 4 hours of treatment are hospitalized for further management.

Problems with Traditional Approach.: With this approach, one third of patients are hospitalized.98 This translates into an estimated medical cost of $1.2 billion annually.98,99 Another pitfall in the traditional ED treatment of asthma is that short encounter times do not allow identification and aggressive treatment of patients with a higher tendency for relapse. This leads to repeated ED visits, additional medical costs, and diminished quality of life.

Observational Approach.: An alternative to hospitalization for patients failing to respond to ED treatment is the use of an extended, short-term intensive protocol for 8 to 12 hours in an observation unit for selected patients (Box 195-5).2 With extended treatment, 80% of such patients can be discharged home.2 Inclusion criteria for observation unit management are failure of standard initial management and continued respiratory distress. Increased risk of relapse is indicated by a history of numerous asthma-related ED or clinic visits within the past year, use of more outpatient medications (including home nebulizers), and longer duration of symptoms.98 Exclusion criteria for observation include unstable vital signs, evidence of impending respiratory failure (PaCO2 > 45 mm Hg, PaO2 < 55 mm Hg), and severe airway restriction (PEFR < 80 L/min after first inhaled beta-agonist treatment). Also considered during selection for observation are factors that correlate with unsuccessful treatment during observation. These include a previous ED visit in the past 10 days, previous intensive care unit admission or intubation, hospitalization during the previous year, three or more ED visits in the past 6 months, use of oral steroids for more than half of the previous year, and peak flow after the third beta-agonist treatment that is less than 32% of predicted.2

A prospective randomized clinical trial of observation versus traditional hospitalization of ED asthma patients who did not “break” in the first 3 or 4 hours of ED treatment found no difference in relapse rates at 8 weeks, but it found observation unit care to be associated with diminished length of stay (9 hours vs. 59 hours), increased patient satisfaction and quality of life, and cost savings of $1000 per patient.2,100 Observation unit patients report greater overall satisfaction and fewer problems with their medical care, communication, emotional support, physical comfort, and special needs.100 Observation has also been shown to have utility in the management of pediatric patients with asthma. Of those who would otherwise require hospitalization, 30 to 70% can be successfully managed as outpatients with the observation unit.101

Atrial Fibrillation

Traditional Approach.: Atrial fibrillation, a relatively common condition that occurs in 2 or 3% of adults, is the most common sustained cardiac dysrhythmia in patients presenting to the ED.102,103 The goals in management of acute atrial fibrillation are hemodynamic stabilization, symptom relief, prevention of thromboembolism, resolution of the dysrhythmia, and exclusion of serious pathologic causes of the dysrhythmia. The majority of patients who present to the ED with new-onset atrial fibrillation or acute atrial fibrillation are hospitalized.80

Problem with Traditional Approach.: Recently, the necessity of admitting the majority of patients with acute atrial fibrillation has been questioned. It is recognized that new-onset atrial fibrillation for most patients is a transient dysrhythmia with no serious precipitants and a benign prognosis. One retrospective analysis of 216 patients admitted for atrial fibrillation found that one third of patients did not actually require admission to the hospital.104

Observational Approach.: The observational approach to new and acute atrial fibrillation has been validated in a number of clinical trials including a randomized clinical trial.105,106 The period of observation is usually 8 to 12 hours. During observation, patients are treated to rectify their dysrhythmia and evaluated for serious precipitants of their condition. After observation, 80 to 90% of patients can be discharged home without hospitalization.

For selected patients (Box 195-6), observation extends the ED evaluation of the patient for serious underlying medical conditions that may have precipitated the arrhythmia, such as AMI or hyperthyroidism. AMI is excluded as a precipitant with serial ECGs and cardiac biomarker testing during 6 to 9 hours and an evaluation for unstable angina. The period of observation is also used to detect structural heart disease with the use of echocardiography when it is appropriate. Patients are excluded from observation if they exhibit hemodynamic instability, comorbid conditions, heart failure, chest pain, or evidence of active coronary artery disease.

Observation is also used to extend the treatment period of the patient. The spontaneous conversion rate for patients with acute atrial fibrillation is 50 to 70% within the first 24 hours.107 Patients who spontaneously convert have a low rate of structural heart disease.107 Those who do not spontaneously convert in the first 8 hours can be converted chemically or electrically.108 After cardioversion, the patient needs to be observed. This is especially true for patients converted with the newer class III antidysrhythmic agents (e.g., ibutilide), which have the potential for serious side effects, such as torsades de pointes (5% of patients), sinus bradycardia, and sinus arrest.108,109 The risk of thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation of less than 48 hours’ duration is less than 1%, so patients who convert can be released home without need for anticoagulation.110

Congestive Heart Failure

Traditional Approach.: CHF is highly lethal; 37% of men and 33% of women die within 2 years of diagnosis. The 6-year mortality rate is 82% for men and 67% for women, which corresponds to a death rate fourfold to eightfold higher than that of the general population of the same age.111 Patients who present to the ED with CHF undergo history taking, physical examination, and investigations including chest radiography. Treatment is begun with oxygenation, diuretics, inotropic agents, and vasodilators as appropriate. Most CHF patients treated in the ED are eventually hospitalized.

Problem with Traditional Approach.: CHF is highly prevalent, affecting approximately 1% of people in their 50s and increasing progressively with age to afflict 10% of people in their 80s.111 More than 2 million Americans have the disease, and 400,000 new cases are diagnosed each year.111 One third of patients require hospitalization each year, one third are readmitted each year, and one third die within 2 years.111 The annual cost to the health care system of managing patients with heart failure admitted to the hospital has been estimated at $28 billion.69 Between 80 and 87% of patients diagnosed with CHF are hospitalized.112,113

Observational Approach.: Observation is a strategy to avoid hospital admission of patients with CHF that results in great cost savings. Selected patients can be safely managed in an observation unit (Box 195-7).112–114 Such patients include those with a high probability of successful treatment with short-term extension of the ED visit. Patients should also have low severity of illness. They should exhibit hypoxia, pulmonary edema, hypotension, evidence of AMI, hemodynamic instability, or serious comorbid conditions.112–114 BNP has been used to streamline decision-making. Patients with BNP levels between 100 and 500 pg/mL are suitable candidates for observation unit care because a large proportion of these patients should be able to be discharged home. The test has a negative predictive value of more than 95% and a positive predictive value of 70 to 95%. It correlates with pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and because its half-life is less than 30 minutes, serial measurements during observation can evaluate the effects of therapeutic interventions.115,116

Therapy and evaluation are a continuation of the initial 2- to 4-hour ED visit for up to 23 hours. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring is performed because up to 30% of CHF patients have dysrhythmias.117 Inotropic agents can be infused and the patient educated about preventable causes of the exacerbation. Therapy may include continuous infusion of a loop diuretic (0.05-0.1 mg/kg/hr) titrated hourly to a net fluid balance of −1 mL/kg/hr. In most patients with acute exacerbation of chronic CHF, the cause of the exacerbation is preventable, such as failure to take medications or dietary indiscretion. The opportunity to provide patient education, medication review, and consultations with dietary and social services as necessary is fully used because this has been shown to improve compliance with therapy.118 Patients are discharged home when their symptoms are adequately controlled, all reversible causes of morbidity are treated or stabilized, and adequate outpatient support and follow-up care are arranged. With observation, the focus of ED care can shift from providing only episodic treatment of CHF patients to providing more comprehensive and preventive care.118 Compared with acute care hospitalization, observation has a much reduced length of stay and significantly lower costs.118,119

Dehydration

Traditional Approach.: Dehydration is often the presenting symptom of an underlying disease state and can affect patients of all ages. Patients are often admitted for intravenous hydration to correct fluid and electrolyte imbalances or for further diagnostic evaluation.

Problem with Traditional Approach.: Patients with dehydration are often hospitalized because short ED visits do not allow full correction of fluid and electrolyte disorders or extensive evaluation for underlying causes. A common cause of ED return visits is dehydration due to initially inadequate therapy and evaluation.120

Observational Approach.: The goals of observation unit therapy are adequate treatment of fluid and electrolyte abnormalities and identification of the underlying cause of symptoms. Appropriate patients for observation include those with acceptable vital signs and mild to moderate dehydration (Box 195-8). They should have self-limited or treatable causes not requiring hospitalization, with mild to moderate electrolyte abnormalities. Most patients with hyperemesis gravidarum can be treated effectively in an observation unit. Patients unsuitable for observation are those with unstable vital signs, cardiovascular compromise, underlying chronic medical illness, severe dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities, or associated conditions not amenable to short-term therapy (e.g., bowel obstruction, diabetic ketoacidosis, and sepsis). Interventions include intravenous rehydration, serial examinations and vital signs, and antiemetics. The patient is released home when there are acceptable vital signs, resolution of symptoms, tolerance to oral fluids, and normal electrolyte values. Patients who do not fulfill the discharge criteria are hospitalized.

Infections

Traditional Approach.: Each year approximately 600,000 patients are hospitalized with pneumonia, at a cost of almost $4 billion.121 Many of these patients are admitted after initial ED evaluation. Physicians often rely on subjective criteria, such as clinical appearance, in selecting patients for hospital admission.122

Problem with Traditional Approach.: There is great variation in the admission rates for pneumonia.123 Emergency physicians tend to overestimate the risk of death in patients with pneumonia, which has resulted in many low-risk patients being hospitalized unnecessarily.122

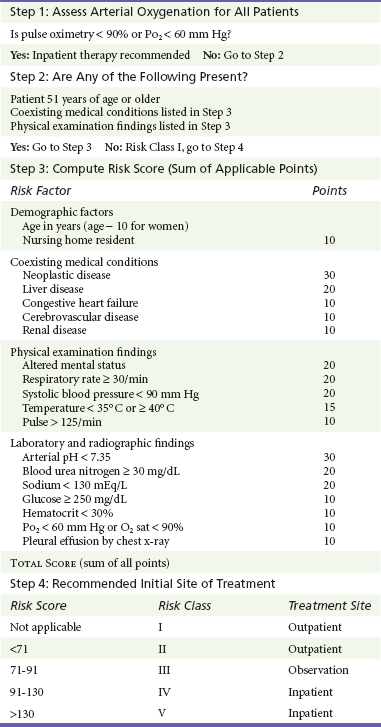

Observational Approach.: Observation is appropriate when the physician is concerned that the patient may not do well as an outpatient (Box 195-9). This concern can be based on the physician’s clinical judgment or a severity of illness index. Fine and associates122 developed a prediction rule to estimate which pneumonia patients would be at higher risk for mortality. They reviewed medical records of more than 14,000 patients hospitalized with pneumonia and identified 14 key clinical variables (e.g., age, sex, coexisting illness, vital signs, and mental status) and 7 key laboratory variables (e.g., blood urea nitrogen, glucose, hematocrit, arterial oxygen, and pleural effusion on chest radiograph). They then weighed each of these variables into a cumulative point total Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and assigned each patient to one of five mortality risk groups ranging from class I, which includes patients with a low risk (30-day mortality risk < 0.5%) who can be treated as outpatients, to class V, which includes patients with a high risk (30-day mortality risk > 30%) who should be treated as inpatients. Patients in class III are at intermediate risk, and traditionally half are admitted and half are treated as outpatients. By use of the PSI to risk stratify patients, physicians can avoid hospitalization of many low-risk patients.124 Intermediate-risk patients (class III) are good candidates for a period of observation to clarify their need for hospitalization. Irrespective of the patient’s risk as judged by PSI, some patients are not appropriate for observation but should be admitted: those with immunocompromise, pulmonary tuberculosis, high suspicion of pulmonary embolism, or hypoxia (Table 195-1).

Pyelonephritis

Traditional Approach.: Pyelonephritis is a serious infection that frequently results in hospitalization for intravenous hydration and antibiotic administration.

Problem with Traditional Approach.: Many patients who are admitted with pyelonephritis are judged retrospectively not to have had the condition. In addition, many patients with pyelonephritis are at very low risk for development of complications.

Observational Approach.: Observation is appropriate for adult, nonpregnant women who appear to have uncomplicated pyelonephritis. Patients receive an initial dose of intravenous antibiotic, intravenous fluids, antiemetic, and antipyretic. Laboratory tests include complete blood cell count, urinalysis, and urine and blood cultures. Patients who are clinically stable and able to tolerate oral fluids are released home after 12 hours of treatment.

Outpatient management of selected patients with pyelonephritis by observation has been shown to be safe and effective. Only 5 to 25% of patients require hospitalization after the period of observation.125,126 At 3-week follow-up examination, 2 to 6% have complications and require hospitalization.125,126 With a period of observation and careful follow-up evaluation, selected patients with pyelonephritis can be successfully managed without hospital admission.126

References

1. Graff, LG, et al. Impact on the care of the emergency department chest pain patient from the Chest Pain Evaluation Registry (CHEPER) study. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:563.

2. McDermott, MF, et al. Comparison between emergency diagnostic and treatment unit and inpatient care in the management of acute asthma. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2055.

3. Graff, L, et al. Emergency physician workload: A time study. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1156.

4. Riggs L, ed. Emergency Department Design. Dallas: American College of Emergency Physicians, 1993.

5. Powers, RD, Guertler, AT. Abdominal pain in the ED: Stability and change over 20 years. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13:301.

6. Rao, PM, Rhea, JT, Rattner, DW, Venus, LG, Novelline, RA. Introduction of appendiceal CT: Impact on negative appendectomy and appendiceal perforation rates. Ann Surg. 1999;229:344–349.

7. Rao, PM, Rhea, JT, Novelline, RA, Mostafavi, AA, McCabe, CJ. Effect of computed tomography of the appendix on treatment of patients and use of hospital resources. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:141–146.

8. McDonald, GP, Pendarvis, DP, Wilmoth, R, Daley, BJ. Influence of preoperative computed tomography on patients undergoing appendectomy. Am Surg. 2001;67:1017–1021.

9. Brenner, DJ, Hall, EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:227–284.

10. Pauker, SG, Kassirer, JP. The threshold approach to medical decision-making. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:1109.

11. Bender, JS. Approach to the acute abdomen. Med Clin North Am. 1989;73:1413.

12. Graff, LG, Radford, MJ, Werne, C. Probability of appendicitis before and after observation. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:503.

13. Thomson, HJ, Jones, PF. Active observation in acute abdominal pain. Am J Surg. 1986;152:522.

14. Banaszak, P. Clinical quality improvement in a multihospital system: The Voluntary Hospitals of America/Pennsylvania experience. Am J Med Qual. 1993;8:56.

15. Graff, L, et al. False-negative and false-positive errors in abdominal pain evaluation: Failure to diagnose acute appendicitis and unnecessary surgery. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1244.

16. Maisel, AS, et al. Impact of age, race, and sex on the ability of B-type natriuretic peptide to aid in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure: Results from the Breathing Not Properly (BNP) multinational study. Am Heart J. 2004;147:1078–1084.

17. Ahn, JS, et al. Development of a point-of-care assay system for high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in whole blood. Clin Chim Acta. 2003;332:51–59.

18. Legnani, C, et al. A new rapid bedside assay for quantitative testing of D-Dimer (Cardiac D-Dimer) in the diagnostic work-up for deep vein thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2003;111:149–153.

19. Kline, JA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a bedside D-dimer assay and alveolar dead-space measurement for rapid exclusion of pulmonary embolism: A multicenter study. JAMA. 2001;285:761–768.

20. Quick, G, Eisenberg, P. Bedside measurement of D-dimer in the identification of bacteremia in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2000;19:217–223.

21. Knudsen, CW, et al. Diagnostic value of a rapid test for B-type natriuretic peptide in patients presenting with acute dyspnea: Effect of age and gender. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6:55–62.

22. Storrow, AB, Gibler, WB. The role of cardiac markers in the emergency department. Clin Chim Acta. 1999;284:187–196.

23. Blomkalns, AL, Gibler, WB. Markers and the initial triage and treatment of patients with chest pain. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2001;1:111–115.

24. McQueen, MB, Holder, K, El-Maraghi, NRH. Assessment of the accuracy of serial electrocardiograms in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1983;105:258.

25. Lee, TH, et al. Evaluation of creatine kinase and creatine kinase MB for diagnosing myocardial infarction: Clinical impact in the emergency room. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:115.

26. Pope, JH, et al. Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1163–1170.

27. Karcz, A, et al. Massachusetts emergency medicine closed malpractice claims: 1988-1990. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:553.

28. Goodacre, S, Dixon, S. Is a chest pain observation unit likely to be cost effective at my hospital? Extrapolation from a randomized controlled trial. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:418.

29. Collinson, PO, et al. Comparison of biomarker strategies for rapid rule out of myocardial infarction in the emergency department using ACC/ESC diagnostic criteria. Ann Clin Biochem. 2006;43(Pt 4):273–280.

30. Jayes, RL, Jr., et al. Do patients’ coronary risk factor reports predict acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department? A multicenter study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:621.

31. Brush, JE, Jr., et al. Use of the initial electrocardiogram to predict in-hospital complications of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1137.

32. Goldman, L, et al. A computer derived protocol to predict myocardial infarction in emergency department patients with acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:797.

33. Selker, HP, et al. Use of the acute cardiac ischemia time-insensitive predictive instrument (ACI-TIPI) to assist with triage of patients with chest pain or other symptoms suggestive of acute cardiac ischemia: A multicenter, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:845.

34. Decker, WW, et al. Continuous 12-lead electrocardiographic monitoring in an emergency department chest pain unit: An assessment of potential clinical effect. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:342.

35. Mark, DB, et al. Prognostic value of a treadmill exercise score in outpatients with suspected coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:849.

36. Gomez, MA, et al. An emergency department based protocol for rapidly ruling out myocardial ischemia reduces hospital time and expense: Results of a randomized study (ROMIO). J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:25.

37. Farkouh, ME, et al. A clinical trial of a chest-pain observation unit for patients with unstable angina. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1882.

38. Roberts, RR, et al. Costs of an emergency department–based accelerated diagnostic protocol vs hospitalization in patients with chest pain: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278:1670–1676.

39. Goodacre, S, et al. Randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of a chest pain observation unit compared with routine care. BMJ. 2004;328:254.

40. Hirsh, J. Heparin. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1565.

41. Burke, DT. Prevention of deep venous thrombosis: Overview of available therapy options for rehabilitation patients. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;79(Suppl):S3–S8.

42. Merli, GJ. Prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in the surgical patient. Clin Cornerstone. 2000;2:15–28.

43. Gotway, MB, et al. Imaging evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 1999;28:129.

44. American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Clinical Policies Committee; ACEP Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Suspected Lower-Extremity Deep Venous Thrombosis: Clinical policy. Critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting with suspected lower-extremity deep venous thrombosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:124.

45. Koopman, MM, et al. Treatment of venous thrombosis with intravenous unfractionated heparin administered in the hospital as compared with subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin administered at home. The Tasman Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:682.

46. Cogo, A, et al. Compression ultrasonography for diagnostic management of patients with clinically suspected deep vein thrombosis: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 1998;316:17.

47. Heijboer, H, et al. A comparison of real-time compression ultrasonography with impedance plethysmography for the diagnosis of deep-vein thrombosis in symptomatic outpatients. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1365.

48. Yavorski, RT, et al. Analysis of 3294 cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in military medical facilities. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;92:231.

49. Fleisher, D. Etiology and prevalence of severe persistent upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:538.

50. Rockall, TA, et al. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316.

51. Bordley, DR, et al. Early clinical signs identify low risk patients with acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. JAMA. 1985;253:3282.

52. Longstreth, GF, Feitelberg, SP. Successful outpatient management of acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: Use of practice guidelines in a large patient series. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:219.

53. Day, SC, et al. Evaluation and outcome of emergency room patients with transient loss of consciousness. Am J Med. 1982;73:15.

54. Graff, LG, et al. Correlation of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research congestive heart failure admission guideline with mortality: Peer Review Organization Voluntary Hospital Association Initiative to Decrease Events (PROVIDE) for congestive heart failure. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:429.

55. Linzer, M, et al. Diagnosing syncope: Part 1. Value of history, physical examination, and electrocardiography. Clinical efficacy assessment project of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:989.

56. Junaid, A, Dubinsky, IL. Establishing an approach to syncope in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1997;15:593.

57. Quinn, JV, Stiell, IG, McDermott, DA, Kohn, MA, Wells, GA. The San Francisco Syncope Rule vs physician judgment and decision making. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:782–786.

58. Bass, E, et al. The duration of Holter monitoring in patients with syncope: Is 24 hours enough? Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1073.

59. Martin, TP, Hanusa, BH, Kapoor, WN. Risk stratification of patients with syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29:459.

60. Quinn, JV, et al. Derivation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule to predict patients with short-term serious outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:224–232.

61. Thiruganasambandamoorthy, V, et al. External validation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule in the Canadian setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:464–472.

62. Reed, MJ, et al. The ROSE (risk stratification of syncope in the emergency department) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:713–721.

63. Costantino, G, et al. Short- and long-term prognosis of syncope, risk factors, and role of hospital admission: Results from the STePS (Short-Term Prognosis of Syncope) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:276–283.

64. Ungar, A, et al. Early and late outcome of treated patients referred for syncope to emergency department: The EGSYS 2 follow-up study. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2021–2026.

65. Dipaola, F, et al. San Francisco Syncope Rule, Osservatorio Epidemiologico sulla Sincope nel Lazio risk score, and clinical judgment in the assessment of short-term outcome of syncope. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:432–439.

66. Serrano, LA, et al. Accuracy and quality of clinical decision rules for syncope in the emergency department: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:362–373.e1.

67. Cunningham, R, Mikhail, MG. Management of patients with syncope and cardiac arrhythmias in an emergency department observation unit. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2001;19:1051.

68. Silverstein, MD, et al. Patients with syncope admitted to medical intensive care units. JAMA. 1982;248:1185.

69. American Heart Association. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2005. Dallas: American Heart Association National Center; 2005.

70. Johnston, SC, et al. Short term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA. 2000;284:2901.

71. Johnston, SC. Clinical practice: Transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1687.

72. Ross, MA, et al. An emergency department diagnostic protocol for patients with transient ischemic attack: A randomized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:109.

73. North Central Regional Trauma Advisory Council. National Trauma Statistics. www.ncrtac-wi.org/index.php?id=30,0,0,1,0,0.

74. Conrad, L, et al. The role of an emergency department observation unit in the management of trauma patients. J Emerg Med. 1985;2:325.

75. Davis, JJ, Cohn, I, Jr., Nance, FC. Diagnosis and management of blunt abdominal trauma. Ann Surg. 1976;183:672.

76. Janzen, DL, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of helical CT for detection of blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:193.

77. Stengel, D, et al. Association between compliance with methodological standards of diagnostic research and reported test accuracy: Meta-analysis of focused assessment of US for trauma. Radiology. 2005;236:102.

78. Livingston, DH, et al. Admission or observation is not necessary after a negative abdominal computed tomographic scan in patients with suspected blunt abdominal trauma: Results of a prospective, multiinstitutional trial. J Trauma. 1998;44:273.

79. Henneman, PL, et al. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage: Accuracy in predicting necessary laparotomy following blunt and penetrating trauma. J Trauma. 1990;39:1345.

80. Chiu, WC, Shanmuganathan, K, Mirvis, SE, Scalea, TM. Determining the need for laparotomy in penetrating torso trauma: A prospective study using triple-contrast enhanced abdominopelvic computed tomography. J Trauma. 2001;51:860.

81. Zantut, LF, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy for penetrating abdominal trauma: A multicenter experience. J Trauma. 1997;42:825.

82. Udobi, KF, Rodriguez, A, Chiu, WC, Scalea, TM. Role of ultrasonography in penetrating abdominal trauma: A prospective clinical study. J Trauma. 2001;50:475.

83. Rosemurgy, AS, et al. Abdominal stab wound protocol: Prospective study documents applicability for widespread use. Am Surg. 1995;61:112.

84. Moss, RL, Musemeche, CA. Clinical judgment is superior to diagnostic tests in the management of pediatric small bowel injury. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1178.

85. van Wijngaarden, MH, Karmy-Jones, R, Talwar, MK, Simonetti, V. Blunt cardiac injury: A 10 year institutional review. Injury. 1997;28:51.

86. Wiener, Y, Achildiev, B, Karni, T, Halevi, A. Echocardiogram in sternal fracture. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:403.

87. Foil, MB, et al. The asymptomatic patient with suspected myocardial contusion. Am J Surg. 1990;160:638.

88. Maenza, RL, Seaberg, D, D’Amico, F. A meta-analysis of blunt cardiac trauma: Ending myocardial confusion. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:237.

89. Collins, JN, et al. The usefulness of serum troponin levels in evaluating cardiac injury. Am Surg. 2001;67:821.

90. Ammons, MA, Moore, EE, Rosen, P. Role of the observation unit in the management of thoracic trauma. J Emerg Med. 1986;4:279.

91. Kerr, TM, et al. Prospective trial of the six hour rule in stab wounds of the chest. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;169:223.

92. Ordog, GJ, Wasserberger, J, Balasubramanium, S, Shoemaker, W. Asymptomatic stab wounds of the chest. J Trauma. 1994;36:680.

93. Aaland, MO, Bryan, FC, 3rd., Sherman, R. Two-dimensional echocardiogram in hemodynamically stable victims of penetrating precordial trauma. Am Surg. 1994;60:412.

94. Mandal, AK, Sanusi, M. Penetrating chest wounds: 24 years of experience. World J Surg. 2001;25:1145.

95. Plummer, D, et al. Emergency department echocardiography improves outcome in penetrating cardiac injury. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:709.

96. Nawar, EW, Niska, RW, Xu, J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2005 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2007;386:1–32.

97. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Asthma Education Programme. Expert Panel Report 2: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health; 1997.

98. Emerman, CL, et al. Multicenter Asthma Research Collaboration investigators: Prospective multicenter study of relapse following treatment for acute asthma among adults presenting to the emergency department. Chest. 1999;115:919.

99. Gouin, S, Patel, H. Utilization analysis of an observation unit for children with asthma. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15:79.

100. Rydman, RJ, et al. Emergency Department Observation Unit versus hospital inpatient care for a chronic asthmatic population: A randomized trial of health status outcome and cost. Med Care. 1998;36:599–609.

101. McConnochie, KM, et al. How commonly are children hospitalised for asthma eligible for care in alternative settings? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:49.

102. Kannel, WB, et al. Epidemiological features of chronic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1018.

103. Feinberg, WM, et al. Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation: Analysis and implications. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:469.

104. Mulcahy, B, et al. New onset atrial fibrillation: When is admission medically justified? Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:114.

105. Koenig, BO, Ross, MA, Jackson, RE. An emergency department observation unit protocol for acute-onset atrial fibrillation is feasible. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:374.

106. Decker, WW, et al. A prospective randomized clinical trial in an emergency department observation unit with acute atrial fibrillation. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:322–328.

107. Danias, PG, et al. Likelihood of spontaneous conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:588.

108. Howard, PA. Ibutilide: An antiarrhythmic agent for the treatment of atrial fibrillation or flutter. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:38.

109. Amin, NB, et al. Sinus bradycardia and multiple episodes of sinus arrest following administration of ibutilide. Heart. 1998;79:628.

110. Weigner, MJ, et al. Risk for clinical thromboembolism associated with conversion to sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation lasting less than 48 hours. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:615.

111. Kannel, WB, Ho, K, Thom, J. Changing epidemiological features of cardiac failure. Br Heart J. 1994;72:S3.

112. Storrow, AB, et al. Emergency department observation of heart failure: Preliminary analysis of safety and cost. Congest Heart Fail. 2005;11:68.

113. Graff, L, et al. Correlation of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research congestive heart failure admission guideline with mortality: Peer Review Organization Voluntary Hospital Association Initiative to Decrease Events (PROVIDE) for congestive heart failure. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:429.

114. Peacock, WF, et al. Heart failure observation units: Optimizing care. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:418.

115. Maisel, AS, et al. Rapid measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:161.

116. Peacock, WF. The B-type natriuretic peptide assay: A rapid test for heart failure. Cleve Clin J Med. 2002;69:243.

117. Vinson, JM, et al. Early readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:1290.

118. Collins, SP, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ED decision making in patients with non–high-risk heart failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:293–302.

119. Peacock, WF, et al. Effective observation unit treatment of decompensated heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2002;8:68–73.

120. Gordon, JA, et al. Initial emergency department diagnosis and return visits: Risk versus perception. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32:569.

121. Garibaldi, RA. Epidemiology of community-acquired respiratory tract infections in adults: Incidence, etiology, and impact. Am J Med. 1985;78:32.

122. Yealy, DM, et al. Effect of increasing the intensity of implementing pneumonia guidelines: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:881.

123. McMahon, LF, Jr., Wolfe, RA, Tedeschi, PJ. Variation in hospital admissions among small areas: A comparison of Maine and Michigan. Med Care. 1989;27:623.

124. Marie, TJ, et al. A controlled trial of a critical pathway for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. CAPITAL Study Investigators. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Intervention Trial Assessing Levofloxacin. JAMA. 2000;283:749.

125. Roberts, R. Management of patients with infectious diseases in an emergency department observation unit. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2001;19:187.

126. Elkharrat, D, et al. Relevance in the emergency department of a decisional algorithm for outpatient care of women with acute pyelonephritis. Eur J Emerg Med. 1999;6:15.