27 Obesity and anti-obesity medical and surgical management

Case, Part 1

SB is a 48-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidemia who presents for weight loss. She reports struggling with weight since childhood but started gaining most significantly after her pregnancies, the last of which was at 28 years of age. She has tried several popular diets, including diet books and diet centres. She has also tried pills for weight loss, both ‘over the counter’ and ordered from television without success. Her current diet consists of a fast food sandwich and large diet soda in the mid-morning ‘on the run’, a piece of fruit with cheese and crackers at home in the mid-afternoon, and large meal with a meat, starch and vegetable for dinner with her family at home four nights a week and eating out the other three. In the evening, she snacks on a piece of cake, ice-cream or popcorn. She craves sweets, especially when stressed, and struggles with large portion sizes. She wants to avoid surgery if possible, but is open to hearing more about it. Her family history is significant for obesity in her mother and two of her three siblings, and hyperlipidaemia in her father and mother. She takes rosiglitazone 2 mg-metformin 1000 mg twice daily, insulin aspart 20 units with each meal, insulin glargine 45 units at bedtime, simvastatin 40 mg daily and lisinopril 20 mg twice daily. Pertinent physical exam findings include a weight of 126 kg, height of 162 cm, and body mass index (BMI) of 48.0 kg/m2. She has a waist of 42 inches. Her labs are unremarkable.

Medical Management

Pharmacotherapy and behaviour modification are the mainstays of non-surgical treatment of obesity, with behaviour modification being the oldest approach to weight loss. Most commonly applied as a program of decreased caloric intake coupled with increased physical activity, behavioural programs have been effective in curtailing weight gain and improving overweight and moderate obesity; however, these behaviour changes and resultant weight loss are difficult for patients to sustain. Additionally, the magnitude of weight loss only modestly improves the health of patients with morbid obesity, those in the greatest need for weight management. Behaviour modification programs usually result in loss of 5–10% of body weight over a 6-month period, but this loss is rarely maintained beyond 6–12 months. High protein, low-carbohydrate diets have had some recent popularity, but a study has shown that at 1 year there was little difference in outcome when such a diet was compared with a conventional diet. Very-low-calorie diets result in more rapid weight loss, but are not a long-term solution without significant, sustained behaviour modification. The risk of malnutrition and need for frequent changes to medication make medical supervision imperative, increasing the cost and decreasing the ease of access to this type of program.

Surgical Management

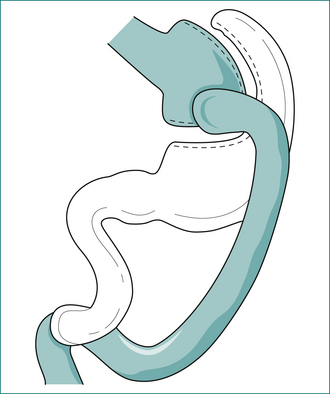

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (GBP) (Fig 27.1) is the most commonly performed procedure in the United States of America and works in three ways. A small pouch of 30-mL volume is created along the lesser curve of the stomach, resulting in restriction to food intake. A 100- to 150-cm Roux limb drains this proximal gastric pouch, resulting in malabsorption. Finally, because ingested food bypasses the main portion of the stomach, certain foods (e.g. sweets) induce the dumping syndrome, which limits patients’ consumption of these foods. After a GBP, 90% of patients lose 50–75% of their excess weight, and this loss is maintained for at least 14 years.

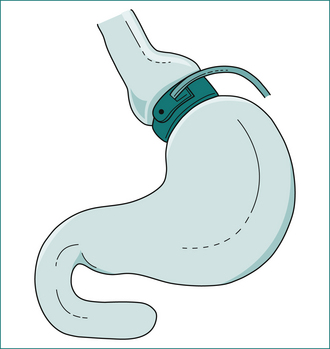

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band

The laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LGB) (Fig 27.2) procedure places an adjustable Silastic™ band around the gastric cardia, thereby creating a small proximal gastric pouch with a restricted outlet to the distal stomach. The LGB has essentially replaced the vertical banded gastroplasty as an effective restrictive-only procedure. While the GBP remains the most commonly performed procedure in the USA, the LGB is the most commonly performed weight-loss procedure in the world. Five-year outcomes reveal that most patients lose 50% to 60% of their excess weight.

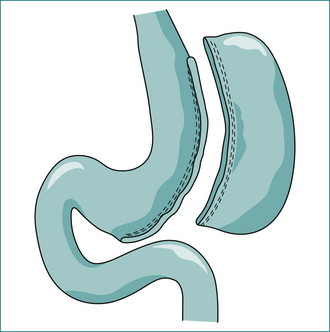

Sleeve gastrectomy

Sleeve gastrectomy (Fig 27.3) has recently become an increasingly common and popular operation. This procedure developed as part of the duodenal switch operation and was used as a staging procedure for extremely obese or high-risk patients. These patients would undergo an initial operation consisting of the sleeve gastrectomy only with the plan to later undergo another surgery to complete the duodenal switch. Weight loss with sleeve gastrectomy only induced sufficient and durable weight loss, making the sleeve gastrectomy alone a reasonable operation. This operation achieves 50–75% excess weight loss without the perioperative risks of the more complex anatomic reconstruction of the GBP.

Outcomes of surgery

Minimally invasive techniques have been used for weight-loss surgery since the first laparoscopic GBP was performed in 1994. Since that time laparoscopic techniques have increasingly dominated weight-loss surgery, with patients realising the expected results regardless of the method of access (open or laparoscopic). These overall results include sustained weight loss with either improvement or complete resolution of comorbidities after surgery. In a recent systematic review of the literature, 22,094 patients were included and the results were as follows: the mean percentage weight loss was 61.2% for all patients, with the most excess weight loss observed with GBP (68.2%). Diabetes resolved in 76.8% of patients, hypertension in 61.7% of patients, and obstructive sleep apnoea in 85.7% of patients.

Conclusions

Obesity remains a significant health concern. Weight-loss surgery is the most sustainable weight-loss option for the majority of morbidly obese adults. As long as the person is motivated to make the lifestyle changes required by the various weight-loss options, he or she can enjoy the benefits of fewer comorbidities, fewer medications, fewer costs and an improved quality of life. In the long term, however, surgery will not be the answer. Not enough surgeons are available to address the current obese adult population, and the prevalence of obesity continues to rise. Education and public awareness are the long-term solution to decrease the incidence of obesity and prevent children from becoming obese adults. It has taken several decades for obesity to reach its current epidemic proportions. It will take many more to get the population back to a healthier weight.

Key Points

Buchwald H., Avidor Y., Braunwald E., et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724-1737.

Calle E.E., Rodriguez C., Walker-Thurmond K., et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of US adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625-1638.

Calle E.E., Thun M.I., Petrelli J.M., et al. Body mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of US adults. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1097-1105.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults with diagnosed diabetes. United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:1066-1068.

Christou N.V., Sarnpalis J.S., Liberman M., et al. Surgery decreases long-term-mortality, morbidity, and health care use in morbidly obese patients. Ann Surg. 2004;240:416-424.

Clegg A.J., Colquitt J., Sidhu M.K., et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of surgery for people with morbid obesity: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Tech Assess. 2002;6:1-153.

Foster G.D., Wyatt H.R., Hill J.O., et al. A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet for obesity. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2082-2090.

Glazer G. Long-term pharmacotherapy of obesity 2000: a review of efficacy and safety. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1814-1824.

Hsu L., Benotti P., Dwyer J., et al. Nonsurgical factors that influence the outcome for bariatric surgery: a review. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:338-346.

Hall J.C., Watts J.M., O’Brien P.E., et al. Gastric surgery for morbid obesity. The Adelaide Study. Ann Surg. 1990;211:419-427.

Howard L., Malone M., Michalek A., et al. Gastric bypass and vertical banded gastroplasty—a prospective randomized comparison and 5-year follow up. Obes Surg. 1995;5:55-60.

Martin L.F., Tan T.L., Horn J.R., et al. Comparison of the costs associated with medical and surgical treatment of obesity. Surgery. 1995;118:599-606.

Mun E.C., Blackburn G.L., Matthews J.B. Current status of medical and surgical therapy for obesity. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:669-681.

National Audit Office. Tackling Obesity in England: Report by the Controller and Auditor General. London: Stationary Office; 2001. No. HC 220 Session 2000–2001

Norris S.L., Zhang X., Avenell A., et al. Efficacy of pharmacotherapy for weight loss in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1395-1404.

O’Meara S., Riemsma R., Shirran L., et al. A rapid and systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of orlistat in the management of obesity. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5:1-81.

Olshansky S.J., Passaro D.J., Hershow R.C., et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1138-1145.

Pories W., Swanson M., MacDonald K., et al. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 1995;222:339-350.

Potteiger C., Paragi P., Inverse N., et al. Bariatric surgery: Shedding the monetary weight of prescription costs in the managed care area. Obes Surg. 2004;14:725-730.

Pournaras D.J., le Roux C.W. Obesity, gut hormones, and bariatric surgery. World J Surg. 2009;33:1983-1988.

Sjostrom L., Lindroos A., Peltonen M., et al. Lifestyle, diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683-2693.

Smith C.D., Herkes S.B., Behrns K.E., et al. Gastric acid secretion and vitamin B12 absorption after vertical Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 1993;218:91-96.

Steinbrook R. Surgery for severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1075-1079.

Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. Available at http://surgeongeneral.gov/topics/obesity/.

Yanovski S.Z., Yanovski J.A. Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:591-602.