Obesity

1. Define the terms “overweight” and “obesity.”

Overweight and obesity are defined as degrees of excess weight that are associated with increases in morbidity and mortality. In 1998, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) published guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of overweight and obesity. The expert panel advocated using specific body mass index (BMI) cutoff points to diagnose both conditions. The BMI is calculated by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by his or her height in meters squared. A BMI (kg/m2) of 25 or less is defined as normal; 25 to 29.9, as overweight; 30 to 34.9, as mild obesity; 35 to 39.9, as moderate obesity; and greater than 40, as severe or morbid obesity.

2. Does fat distribution affect the assessment of risk in an overweight or obese patient?

Yes. Accumulation of excessive adipose tissue in a central—or upper—body distribution (android or male pattern) is associated with a greater risk of adverse metabolic health consequences than lower-body obesity (gynoid or female pattern). Abdominal adiposity is an independent predictor of risk for diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and coronary artery disease. The absolute amount of intraabdominal or visceral fat is most closely linked to these adverse health risks.

3. Explain the role of waist circumference in risk stratification.

For this reason, the waist circumference is the favored measure for risk stratification on the basis of fat distribution. Men with a waist circumference greater than 40 inches (> 102 cm) and women whose waist circumference is greater than 35 inches (> 88 cm) have increased risk. Waist circumference is most useful for risk stratification in people with a BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m2. In this intermediate-risk group, those with increased waist circumference should undertake greater efforts directed at preventing further weight gain, whereas those with a smaller waist circumference can be reassured that their weight does not pose major health hazards.

4. How is waist circumference measured?

Waist circumference should be measured with a tape measure parallel to the floor at the level of the iliac crest at the end of a relaxed expiration.

5. What adverse health consequences are associated with obesity?

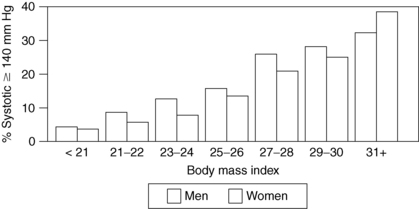

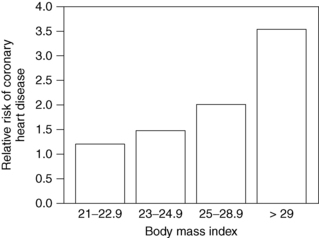

Obesity is clearly associated with diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, degenerative arthritis, gallbladder disease, and cancer of the endometrium, breast, prostate, and colon. It has also been associated with urinary incontinence, gastroesophageal reflux, infertility, sleep apnea, and congestive heart failure. The incidence of these conditions rises steadily as body weight increases (Figs. 7-1 and 7-2). Risks increase with even modest weight gain. Health risks are magnified with advancing age and a positive family history of obesity-related diseases.

6. Summarize the economic consequences of obesity.

The total direct and indirect health care costs associated with obesity were estimated to be $147 billion in 2008. In 2006, annual medical spending was $1429 (42%) greater for obese people than for normal-weight people. Almost 90% of the increase in costs attributable to the care of obese people is due to the rise in the prevalence of obesity. In addition, the NIH estimated that Americans pay $44 billion for weight loss products and services.

7. What are the psychological complications of obesity?

Situational depression and anxiety related to obesity are common. The obese person may suffer from discrimination, which contributes further to difficulty with poor self-image and social isolation. It may be difficult in some patients to determine whether depression is accelerating weight gain or whether weight gain is exacerbating an underlying depression, but treating both conditions may improve quality of life. Work by the Rudd Center and other groups has highlighted the bias that obese patients experience even from doctors who care for them. It is important for treating physicians to at least be aware of a tendency to blame obese patients for their condition and to compensate for this common bias as best they can if present.

Obesity has reached epidemic proportions in the United States. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted by the federal government uses direct measures of height and weight in a representative sample of Americans to estimate the prevalence of obesity. The prevalence of obesity increased significantly during the 1980s and 1990s but has now leveled off. The latest data from the NHANES showed that in 2009 to 2010, 35.7% of adults in the United States had a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2. This rate of obesity has not changed significantly from those in 2003 through 2008. The prevalence of overweight (BMI > 25 kg/m2) was found to be 68.8%. The prevalence of severe obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m2) was 6.3% in the latest dataset. In children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years, the prevalence of obesity was found to be 16.9%, not changed from 2007 to 2008 prevalences.

9. What caused the dramatic rise in the prevalence of obesity in the 1980s and 1990s?

The prevalence of obesity indeed rose over this short period; it seems that the primary culprit is a changing environment that promotes increased food intake and reduced physical activity. This statement should not be taken to mean, however, that body weight is not subject to physiologic regulation. The control of body weight is complex, with multiple interrelated systems controlling caloric intake, macronutrient content of the diet, energy expenditure, and fuel metabolism.

10. Describe the current model for obesity as a chronic disease.

Obesity is now viewed as a chronic, often progressive metabolic disease much like diabetes or hypertension. This view requires a conceptual shift from the previous widely held belief that obesity is simply a cosmetic or behavioral problem. Development of obesity requires a period of positive energy balance during which energy intake exceeds energy expenditure. Maintaining energy balance is one of the most important survival mechanisms of any organism. A sustained negative imbalance between energy intake and expenditure is potentially life-threatening within a relatively short time. To maintain energy balance, the organism must assess energy stores within the body; assess the nutrient content of the diet; determine whether the body is in negative energy or nutrient balance; and adjust hormone levels, energy expenditure, nutrient movement, and ingestive behavior in response to these assessments.

11. Do abnormal genes cause obesity?

Obesity is clearly more common in people who have family members who are also obese. Genetics appears to be responsible for 30% to 60% of the variance in weight in most populations. The problem of human obesity, however, involves an interaction between genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers. The genes that we possess to regulate body weight evolved somewhere between 200,000 and 1 million years ago, at which time the environmental factors controlling nutrient acquisition and habitual physical activity were dramatically different. A number of single gene defects have been identified that cause severe childhood obesity. These include mutations in the leptin gene, leptin receptor, the MC4R gene, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and SIM-1. However, these mutations are quite rare, explaining less than 8% of severe early-onset obesity. Genome-wide association studies have identified more than 20 genes that are associated with common forms of human obesity. The most common of these is the FTO gene. The allele of this gene that is associated with weight gain is present in 15% of humans. However, the weight gain associated with this high-risk allele is only 3 kg. Thus, common human obesity appears to be the result of alterations in a large number of genes, each having relatively small effects (polygenic).

Leptin is a hormone secreted exclusively by adipose tissue in direct proportion to fat mass. It was discovered in 1994. Leptin acts through receptors located on neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus and other brain regions to regulate both food intake and energy expenditure. Changes in leptin levels in the hypothalamus alter the production of a number of neuropeptides, including pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and Agouti-related peptide (AGRP).

13. Does leptin deficiency cause human obesity?

There are a handful of cases in which genetic deficiency of either leptin or its receptor has been found to cause severe early-onset obesity. Treating leptin-deficient humans with leptin results in dramatic weight loss. However, leptin levels are typically higher in obese than in lean humans in proportion to the former’s greater fat mass. Studies in which recombinant human leptin was administered to typical obese humans produced minimal weight loss. These findings suggest that common forms of human obesity are associated with leptin resistance, not leptin deficiency.

14. Explain how the melanocortin system is involved in weight regulation.

Alpha-melanocortin (alpha-melanocyte–stimulating hormone [α-MSH]) is one of the hormone products of the POMC gene. This neuropeptide acts in the hypothalamus on melanocortin receptors, particularly the MC4-R subtype, to regulate body weight. By stimulating the MC4-R, α-MSH inhibits food intake, whereas the natural antagonist, Agouti-related peptide (AGRP), which is also made in the hypothalamus, stimulates food intake. MC4-R agonists have been developed. Although these drugs decrease food intake and reduce body weight in obese rodents, they have not been found to be useful as single agents in obese humans. The failure of these drugs and others that work through hypothalamic regulatory pathways to produce significant weight loss in obese humans has raised questions about the role of these systems in common forms of human obesity.

Ghrelin is a hormone originally identified as a growth hormone–releasing hormone produced by the stomach and proximal small intestine that appears to regulate appetite. Ghrelin levels rise before meals and promptly drop following food intake. Self-reported hunger mirrors serum ghrelin levels. Twenty-four-hour ghrelin levels rise when people go on an energy-restricted diet and are dramatically reduced after gastric bypass surgery. Ghrelin has been described as a “hunger hormone” and is another possible target for weight loss drugs. The bioactive form of the hormone, acylated ghrelin, has a fatty acid attached to the parent hormone. Drugs that alter the production of acylated ghrelin are also being investigated.

16. Does a decrease in energy expenditure play a role in the development of obesity?

The development of obesity requires an imbalance between caloric intake and caloric expenditure. For fat mass to increase, there must be an imbalance between the amount of fat deposited and the amount of fat oxidized. One possibility is that people become obese because of a reduction in their energy expenditure. Despite the common idea that a “low metabolic rate” predisposes to obesity, there is little evidence that this is true.

17. What are the components of energy expenditure?

Basal metabolic rate (BMR): The amount of energy needed to maintain body homeostasis by maintaining body temperature, maintaining cardiopulmonary integrity, and maintaining electrolyte stability.

Basal metabolic rate (BMR): The amount of energy needed to maintain body homeostasis by maintaining body temperature, maintaining cardiopulmonary integrity, and maintaining electrolyte stability.

Thermic effect of food: A relatively small component (5% to 10%) that represents the energy cost associated with the assimilation of a meal.

Thermic effect of food: A relatively small component (5% to 10%) that represents the energy cost associated with the assimilation of a meal.

Physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE): This is the most variable component. It can account for as little as 10% to 20% of total energy expenditure in people who are sedentary or as much as 60% to 80% of total energy expenditure in training athletes. PAEE increases with planned physical activity or with activities of daily living, such as stair climbing and even fidgeting. The unconscious component of physical activity has been termed non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) and may be a regulated parameter.

Physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE): This is the most variable component. It can account for as little as 10% to 20% of total energy expenditure in people who are sedentary or as much as 60% to 80% of total energy expenditure in training athletes. PAEE increases with planned physical activity or with activities of daily living, such as stair climbing and even fidgeting. The unconscious component of physical activity has been termed non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) and may be a regulated parameter.

18. Explain the concept of energy balance.

When an individual is weight stable, total daily energy expenditure equals total daily energy intake. Total energy expenditure is linearly related to lean body mass. Studies that have used sophisticated methods for measuring energy expenditure have clearly shown that obese people consume more calories than lean people. The obese person who says that he or she eats only a small amount but is gaining weight may be telling the truth in the short term, but over longer periods, high caloric intakes are required to maintain the obese state. Although reduced levels of PAEE may predispose to obesity, BMR is not reduced in obese people. The central cause of obesity is the failure to couple energy intake to energy expenditure accurately over time.

19. Are there other factors involved in the increase in the prevalence of obesity?

Over the past 10 years, investigators have identified a range of novel environmental factors that may be related to the increase in obesity seen over the past 40 years. One area that has received a good deal of attention is reduced sleep time. It is clear that on average Americans are sleeping less than they did 50 years ago. Epidemiologic studies have shown that shortened sleep time is associated with obesity, and experimental studies have shown that sleep restriction is associated with insulin resistance, increased appetite, and a change in fat oxidation. Medication use is another factor that may be involved in promoting obesity. Widely used medications that promote weight gain include newer antipsychotic medications, sulfonylureas, insulin, thiazolidinediones, and progesterone-containing birth control medications. Other novel factors that are potentially involved include the aging of the population as well as increases in the number of ethnic minorities in the United States, the use of climate control systems in houses and public buildings (mice housed in thermoneutral environments weigh more than mice housed at lower temperatures), and environmental toxins (some studies suggest that adipose tissue increases in response to environmental toxins in an effort to sequester them).

20. What options are available for treating the obese patient?

Treatment options for overweight or obese patients include diet, exercise, pharmacotherapy, surgery, and combinations of these modalities. The specific modality should be based on the individual’s BMI and associated health problems. A more aggressive treatment approach is warranted in those whose BMI is higher and those with weight-related health problems. Behavioral approaches can be advocated for all overweight and obese patients. Pharmacologic treatment should be considered in those whose BMI is greater than 27 kg/m2 in the presence of medical complications or greater than 30 kg/m2 in the absence of medical complications. Surgical treatment is currently reserved for those with a BMI greater than 40 kg/m2 and those with a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2 and comorbidities. Evidence suggests that bariatric surgery is also helpful for patients with diabetes whose BMI is less than 35 kg/m2.

21. What is the goal of a weight loss program?

Before discussing the treatment options with a patient, it is important to decide the goal of the treatment program. Many obese patients have unrealistic expectations about the amount of weight that they might lose through a weight loss program. Most would like to achieve ideal body weight and are disappointed if they lose only 5% to 10% of their initial weight. These desires stand in stark contrast to the magnitude of weight loss that has been seen with all treatment modalities short of bariatric surgery. The most effective diet, exercise, or drug treatment programs available result in roughly a 5% to 10% weight loss in most people.

22. Is a 5% to 10% reduction helpful in terms of health improvement?

Loss of 5% to 10% of body weight has been associated with improvements in health-related measures, such as lower blood pressure, reductions in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, improved functional capacity, and a markedly lower risk of diabetes. Most experts now believe that a sustained 5% to 10% weight loss (e.g., a weight loss of 11 to 12 lb for someone who initially weighed 220 lb) is a realistic goal with measurable health benefits. Alternatively, prevention of further weight gain may be a reasonable and attainable goal, or the health care provider may simply encourage the patient to focus on eating and activity habits and not on a weight goal at all.

23. How can a patient’s readiness to change his or her diet or physical activity be assessed?

Stages of change theory can help the clinician focus counseling activities within the context of a brief office visit. Prochazka has hypothesized six predictable stages through which a person passes before he or she is able to change a long-standing behavior, such as diet, physical activity pattern, or smoking: precontemplative, contemplative, planning, action, maintenance, and relapse. Identifying the stage that the patient is in and targeting counseling efforts to that stage may improve the effectiveness of the counseling activities.

24. What is “motivational interviewing,” and how is it used in counseling an obese patient?

Motivational interviewing is a counseling style that was developed for use with alcoholics. The method is useful for interacting with patients who are ambivalent about changing their diet or physical activity behaviors. The strategies used focus on resolving this ambivalence by having patients explore reasons why they want to change and reasons why they find their current behavior more comfortable. The method grows out of the idea that motivation cannot be created, but that for many patients the motivation is already there, it simply needs to be identified and redirected.

25. Discuss the role of diet in the treatment of the obese patient.

The mainstays of dietary modification in weight loss therapy have been diets low in fat and reduced in calories. Compelling evidence in favor of this approach comes from the Diabetes Prevention Project and other related trials in individuals at high risk for the development of diabetes. Whatever changes the person makes must be sustained to be beneficial. The clinician should assess the current diet with a good nutritional history, which may involve a verbal 24- or 72-hour intake recall. Alternatively, the patient may keep a written 3- to 7-day food diary. Assessing meal pattern is important, because many people skip breakfast and eat lunch erratically. Attention should be paid to how often the person eats out, especially fast food. Many patients are able to identify key foods that are a problem for their weight loss efforts. Small, gradual changes may be more successful than drastic ones.

26. Should patients be encouraged to attend a commercial weight loss program?

Yes. Most people know what they should eat. The problem is that they either do not pay attention to what they eat or do not find a “healthy diet” palatable. The use of commercial programs, such as Weight Watchers, can provide reasonable nutritional counseling along with social support that often cannot be provided in the context of a busy office practice. Many patients are surprised at the cost of these programs, which may be a deterrent to their continued use. However, this kind of program involves no risk and may be cheaper in the long term than pharmacologic treatment. The scientific literature supports the notion that for many people, commercial weight loss programs are a reasonable option.

27. Are meal replacements useful in a weight loss program?

For some people, it is difficult to control calories through self-selected meals. Time may not be available for food preparation, and convenience may override health concerns. For such people, meal replacements—calorie, nutritionally complete meal—are a reasonable option with scientifically proven effectiveness if used as a long-term strategy. In fact, this approach was used in the NIH-funded Look Ahead Trial, and participants who were in the highest quartile of meal replacement use were four times as likely to meet their weight loss goals.

28. What are low-calorie and very-low-calorie diets? When should their use be considered?

A very-low-calorie diet (VLCD) is a nutritionally complete diet of 800 kcal/day that produces rapid weight loss. A low-calorie diet (LCD) contains between 800 and 1000 kcal/day. Commercially available products typically consist of liquid meals that have been supplemented with essential amino acids, essential fatty acids, vitamins, and micronutrients taken four or five times per day. Supplementing the commercial product with fruits and vegetables converts a VLCD to an LCD and may make the diet more tolerable to patients. Data suggest that VLCDs and LCDs may produce a degree of weight loss that is better than those with traditional dietary approaches and closer to what is seen with bariatric surgery. Such diets may also be useful for the patient who needs short-term weight loss for a diagnostic or surgical procedure. Gallstone formation is a recognized complication of VLCDs and LCDs.

29. What is the Atkins Diet? Does it work?

The Atkins Diet is a severely carbohydrate-restricted (< 20 g/day during the induction phase) diet. The severe carbohydrate restriction produces what Dr. Robert Atkins calls “benign dietary ketosis,” which he argues suppresses appetite. The diet has few other restrictions. Several studies support the idea that the Atkins Diet produces more weight loss than a low-fat diet over 6 months but that long-term weight loss is comparable to that seen with diets that are higher in carbohydrate and lower in fat. These studies have shown no adverse effects on blood lipid levels. The Atkins Diet can be difficult for people to adhere to long term.

30. What drugs are available to treat obesity?

31. Are phentermine and amphetamine related?

Yes. Phentermine is chemically related to amphetamine and works predominantly on the neurotransmitter norepinephrine to reduce appetite. The addictive effects of amphetamine are thought to be due to its actions on the neurotransmitter dopamine. Phentermine has substantially fewer dopaminergic effects than amphetamine and thus has minimal potential for addiction.

32. Is phentermine effective? What is the usual dose?

Compared with placebo, phentermine produces roughly a 5% weight loss in 50% to 60% of those who take it. The dose used ranges from 15 to 37.5 mg/day. It is the most widely prescribed weight loss medication.

33. Discuss the side effects of phentermine.

Phentermine is a central stimulant and can cause hypertension, tachycardia, nervousness, headache, difficulty sleeping, and tremor in some people. It should not be used in people with uncontrolled hypertension. Blood pressure should be monitored closely after initiation of this medicine. There is no evidence that, when used alone (in contrast to the combination of phentermine with fenfluramine), it is associated with cardiac valvular or pulmonary vascular toxicity. Phentermine is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) only for 3-month use. However, it is often prescribed “off label” for longer than 3 months. Evidence of the safety of phentermine comes from the fact that has been widely prescribed longer than any other weight loss agent, and there has been no evidence of serious long-term side effects.

34. How does orlistat work? What is the usual dose?

Orlistat is a pancreatic lipase inhibitor. At prescription strength, 120 mg three times a day with meals, it reduces the absorption of dietary fat by roughly 30% by inhibiting the enzyme responsible for fat digestion. The average weight loss seen is about 5% to 8%. This medication may be preferred in people with mood disorders, heart disease, or poorly controlled hypertension. A 60-mg form is approved by the FDA and available over the counter. This strength is less effective than the prescription strength, giving roughly a 2% to 4% weight loss.

35. What are the side effects of orlistat?

The main side effects of orlistat are due to the malabsorption of fat that it causes. Patients using the agent who eat a high-fat meal experience greasy stools and may even have problems with incontinence of stool. If the patient chooses to skip the medication, he or she can eat a high-fat meal without side effects and without the benefit that the medication would otherwise provide. The FDA has approved orlistat for long-term use, and there is no specific mention in the package insert of when it should be stopped. Because of the potential to cause fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies, patients should be instructed to take a multiple vitamin daily. Orlistat should be used with caution in those taking warfarin (Coumadin) and is contraindicated in those undergoing cyclosporin therapy.

36. Discuss the use of lorcaserin.

Lorcaserin is the most recently FDA-approved weight loss medication. It is a selective 5-HT2C receptor agonist that modifies serotonin signaling to reduce food intake. Lorcaserin is indicated as an adjunct to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity for long-term weight management in adults with an initial BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater or with an initial BMI 27 kg/m2 or greater and at least one weight-related comorbid condition. Average weight loss with lorcaserin was approximately 4% to 6% in clinical trials.

37. Discuss the role of bupropion in the treatment of obesity.

A number of studies demonstrate that bupropion can produce gradual weight loss over as long as 1 year in many people. This medication is not approved by the FDA for weight loss. Bupropion may be useful in obese patients with depression severe enough to warrant pharmacotherapy.

38. Discuss the use of phentermine plus topiramate in obesity treatment.

Phentermine plus topiramate is the most recently FDA-approved medication for weight loss. Topiramate is indicated for the treatment of seizure disorder and migraine. In clinical trials, individuals taking phentermine plus topiramate had a mean weight loss of 8% to 10%. The recommended dose is phentermine 7.5 mg plus topiramate extended release 46 mg. The higher dosage of phentermine 15 mg plus topiramate 92 mg can also be prescribed. The combination medication cannot be used during pregnancy because data have shown that fetuses exposed to topiramate during the first trimester were at increased risk of oral clefts (cleft lip with or without cleft palate). Females of reproductive age should have a negative pregnancy test result before starting the medication, should use effective contraception, and should have pregnancy tests every month while taking the medication. Additionally, the medication cannot be used in patients with glaucoma or hyperthyroidism.

39. Are there any new weight loss drugs on the horizon?

A number of weight loss medications have been reviewed by the FDA over the past several years. Several glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists are available for the treatment of diabetes. Exenatide and liraglutide are being evaluated with the intent to seek FDA approval for a weight loss indication. A bupropion-naltrexone combination is also being evaluated but has not yet received FDA approval.

40. How long will a weight loss medication need to be taken?

Medications used to promote weight loss will work only as long as they are taken. If a patient loses weight while taking a medication and then stops using it, he or she is likely to regain the lost weight. If a physician and a patient decide to try a weight loss medication, it should be taken for a minimum of 1 to 3 months to determine whether the patient will experience a weight loss benefit. Then some form of long-term use should be considered, given the available information about the risks and potential benefits of the medication. There are also data supporting the intermittent use of weight loss medications.

41. Discuss the role of exercise in a weight loss program.

Increased physical activity appears to be a central part of a successful weight loss program. Although exercise does not produce much added weight loss over diet alone in the short run, it appears to be extremely important in maintaining the reduced state. The National Weight Control Registry is a group of 3000 people who were identified because they successfully lost 30 lb and kept it off for at least 1 year. They self-report 2000 kcal/week of planned physical activity (60-80 min/day on most days of the week). A discussion of physical activity with a patient should begin with a physical activity history. Ask about the frequency of engaging in planned physical activity. Then ask about hours per day of television viewing, computer time, and other sedentary activities. Finally, discuss activities of daily living, including work-related activities. Assess the individual’s readiness to change his or her physical activity level.

42. How much physical activity is necessary to prevent weight gain as opposed to maintaining a reduced weight?

In 2008, the U.S. government published physical activity guidelines for Americans. These guidelines suggest that all adults should do 2 hours and 30 minutes a week of moderate-intensity or 1 hour and 15 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity. In addition, they advise that muscle-strengthening activities involving all major muscle groups be performed on 2 or more days per week. This level of activity is designed to prevent weight gain. It appears that 60 to 90 minutes per day of moderate physical activity may be needed for maintenance of weight loss.

43. What are pedometers? How are they used?

Pedometers are small devices that clip to the waistbands of clothing. They can be used both to assess usual physical activity and to make and monitor physical activity goals. The usual number of steps taken by an average person is 6,000 per day. The recommended number of steps to prevent weight gain is 10,000 per day. People in the National Weight Control Registry using physical activity to maintain a reduced obese state average 12,000 steps/day.

44. What are the common types of weight loss surgery?

Restrictive surgery limits the amount of food the stomach can hold and slows the rate of gastric emptying. The most commonly performed restrictive operation is laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding (LAP-BAND). A newer operation, the sleeve gastrectomy, markedly restricts gastric capacity in an irreversible manner and appears to be more effective than laparoscopic banding, although it also carries greater risks of complications. The restrictive-malabsorptive Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) procedure combines gastric restriction with selective malabsorption and produces greater weight loss. This procedure may be performed through an open incision or laparoscopically. The less commonly performed biliopancreatic diversion–duodenal switch procedure produces even more malabsorption and greater weight loss. Although these malabsorptive procedures produce more rapid and profound weight loss, they also put patients at risk of complications, such as vitamin deficiencies and protein-energy malnutrition. Restrictive procedures are considered simpler and safer but may result in less long-term weight loss.

45. Who are good candidates for surgical treatment of obesity?

Eligible patients are those with a BMI greater than 40 kg/m2 without comorbidities or a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2 with comorbidities, such as diabetes, sleep apnea, reflux, hypertension, and degenerative joint disease (DJD); patients with a family history of comorbidities; patients for whom other forms of therapy have failed; and patients with no serious cardiac, pulmonary, or psychiatric disease. Bariatric surgery is increasingly being performed in adolescents who are severely obese, who have gone through puberty, and for whom other forms of treatment have failed.

46. What are the expected outcomes and health benefits of weight loss surgery?

Bariatric surgery is the most effective weight loss treatment available for those with clinically severe obesity. In one meta-analysis, the overall percentage of excess weight loss for all surgery types was 61.2% (see Buchwald et al, 2004). This translates into roughly a 30% overall loss compared with preoperative weight. Weight loss is greater after the combined restrictive-malabsorptive procedures than after the restrictive procedures. In the meta-analysis, diabetes completely resolved in 77% of patients and resolved or improved in 86% of patients following bariatric surgery. Two other series have reported resolution of diabetes in 83% and 86% of patients (see Schauer et al, 2003 and Sugarman et al, 2003). In the meta-analysis, hyperlipidemia improved in 70% or more of the patients, hypertension resolved in 62% and resolved or improved in 79% of patients, and obstructive sleep apnea resolved in 86%. Hypertension improves in many patients but is more resistant to improvement than diabetes or sleep apnea.

47. What is the mortality rate associated with bariatric surgery?

The surgical mortality rate associated with bariatric surgery is 0.1% to 2.0%. In the meta-analysis previously cited, mortality at 30 or fewer days was 0.1% for the purely restrictive procedures, 0.5% in patients undergoing gastric bypass procedures, and 1.1% in patients undergoing biliopancreatic diversion–duodenal switch procedures (see Buchwald et al, 2004). In a later prospective observational study, the 30-day rate of death among patients who underwent RYGB or laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding was 0.3%, and a total of 4.3% of patients had at least one major adverse outcome. Common causes of death among patients undergoing bariatric surgery included pulmonary embolism and anastomotic leaks. Factors that have been found to contribute to increased mortality include lack of experience on the part of the surgeon or the program, advanced patient age, male sex, severe obesity (BMI > 50 kg/m2), and coexisting conditions. Risk is higher in low-volume programs.

48. What are the most common complications of bariatric surgery?

Nonfatal perioperative complications include venous thromboembolism, anastomotic leaks, wound infections, bleeding, incidental splenectomy, incisional and internal hernias, and early small bowel obstruction. Stomal stenosis or marginal ulcers (occurring in 5% to 15% of patients) present as prolonged nausea and vomiting after eating or inability to advance the diet to solid foods. These complications are treated by endoscopic balloon dilatation and acid suppression therapy, respectively. Abdominal and incisional hernias occur in roughly 30% of patients following open RYGB. Dumping syndrome following simple sugar intake, especially added sugars, has been reported in as many as 76% of RYGB patients. To prevent dumping syndrome, patients should be encouraged to consume frequent, small meals and to avoid fruit juices and added sugars.

49. What is a rare cause of hypoglycemia following RYGB?

Post–gastric bypass hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia is increasingly being recognized. Some investigators have hypothesized that changes in gut hormones such as GLP-1 following gastric bypass may promote beta-cell hyperplasia and predispose to this condition. Unlike patients with insulinomas, these patients often experience severe hypoglycemia following the ingestion of carbohydrates. Initial descriptions emphasized the presence of nesidioblastosis, or beta-cell hyperplasia as a cause and demonstrated the value of partial pancreatectomy as a treatment in severe cases. More recently, studies have suggested that most patients with this syndrome can be treated by modifying the diet to include less carbohydrate and increasing the consumption of slowly absorbed (low glycemic index) carbohydrates in the context of mixed meals. While dietary carbohydrate restriction is the principal treatment for hypoglycemia following gastric bypass surgery, a number of medications have been found to be of use including acarbose, calcium channel blockers, diazoxide, and octreotide.

50. What vitamin and micronutrient deficiencies are patients at risk for following bariatric surgery?

By bypassing the stomach, duodenum, and varying portions of the jejunum and ileum, malabsorption of thiamine, iron, folate, vitamin B12, calcium, and vitamin D may occur. In general, the greater the degree of malabsorption, the higher the risk of nutritional deficiencies. To prevent deficiencies, patients should routinely be discharged from the hospital with daily vitamin and mineral supplementation that contains between 1.5 and 1.8 mg thiamine, 28 and 40 mg elemental iron, 500 μg oral B12, 400 μg folate, 1200 to 1500 mg calcium, and 800 to 1200 IU vitamin D.

51. What laboratory tests should be performed to follow up on a patient who has had weight loss surgery?

The following laboratory tests should be performed preoperatively and at 6-month intervals for the first 2 years, followed by annual assessments thereafter: complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, and measurements of hemoglobin A1C (for diabetic patients), ferritin, folate, vitamin B12, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, and parathyroid hormone. With more extensive procedures, such as biliopancreatic diversion, protein malnutrition and deficiencies of the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) may occur. Some patients in whom iron deficiency anemia develops following weight loss surgery require treatment with parenteral iron. With judicious monitoring and adequate supplementation, all of these deficiencies are largely avoidable and treatable.

Buchwald, H, Avidor, Y, Braunwald, E, et al, Bariatric surgery. a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004;292:1724–1728.

Dansinger, ML, Gleason, JA, Griffith, JL, et al, Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction. a randomized trial. JAMA 2005;293:43–53.

Fidler, MC, Sanchez, M, Anderson, CM, et al, BLOSSOM Clinical Trial Group. A one-year randomized trial of lorcaserin for weight loss in obese and overweight adults. the BLOSSOM trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:3067–3077.

Finkelstein, EA, Trogdon, JG, Cohen, JW, et al, Annual medical spending attributable to obesity. payer- and service-specific estimates. Health Affairs 2009;28:822–831.

Flegal, KM, Carroll, MD, Kit, BK, et al. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults. JAMA. 2012;307:491–497. 1999–2010

Foster, GD, Wyatt, HR, Hill, JO, et al. A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet for obesity. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2082–2090.

Hession, M, Rolland, C, Kulkarni, U, et al. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of low-carbohydrate vs. low-fat/low-calorie diets in the management of obesity and its comorbidities. Obes Rev. 2009;10(1):36–50.

Heymsfield, SB, Van Mierlo, CA, Van Der Knapp, HC, et al, Weight management using a meal replacement strategy. meta and pooling analysis. Int J Obesity Relat Metab Disord 2003;27:537–549.

Knowler, WC, Barrett-Conner, E, Fowler, SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403.

Kral, JG, Naslund, E. Surgical treatment of obesity. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3:574–583.

Kushner, RF. Obesity management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;36:191–210.

Kushner, RF, Bessesen, DH. Treatment of the obese patient. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press.; 2007.

Lauderdale, DS, Liu, K, et al, Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between objectively measured sleep duration and body mass index. the CARDIA Sleep Study. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:805–813.

Li, Z, Maglione, M, Tu, W, et al, Meta-analysis. pharmacologic treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:532–546.

Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium, Flum, DR, Belle, SH, King, WC, et al. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:445–454.

Maggard, MA, Shugarman, LR, Suttorp, M, et al, Meta-analysis. surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:547–559.

Maria, EJ. Bariatric surgery for morbid obesity. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2176–2183.

McTigue, KM, Harris, R, Hemphill, B, et al, Screening and interventions for obesity in adults. summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Med 2003;139:933–1049.

Mechanick, JI, Kushner, RF, Sugerman, HJ, et al, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery medical guidelines for clinical practice for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient, Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:S1–70.

, National Institutes of Health. The practical guide to the identification, evaluation and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Obesity Res. 1998;6(Suppl 12)

Ogden, CL, Carroll, MD, Kit, BK, et al. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–490. 1999–2010

Ramachandrappa, S, Farooqi, IS. Genetic approaches to understanding human obesity. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):6. 2080

Samaha, FF, Iqbal, N, Seshadri, P, et al. A low-carbohydrate as compared with a low-fat diet in severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2074–2081.

Schauer, PR, Burguera, B, Ikramuddin, S, et al. Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 2003;238:467–484.

Service, GJ, Thompson, GB, Service, FJ, et al. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia with nesidioblastosis after gastric-bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:249–254.

Shah, M, Simha, V, Garg, A. Long-term impact of bariatric surgery on body weight, comorbidities, and nutritional status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4223–4231.

Snow, V, Barry, P, Fitterman, N, et al, Pharmacologic and surgical management of obesity in primary care. a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:525–531.

Sugarman, HJ, Wolfe, LG, Sica, DA, et al. Diabetes and hypertension in severe obesity and effects of gastric bypass-induced weight loss. Ann Surg. 2003;237:751–756.

Tsai, AG, Wadden, TA, Systematic review. an evaluation of major commercial weight loss programs in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:56–66.

Tuomilehto, J, Lindstrom, J, Eriksson, JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–1350.

Wadden, TA, West, DS, Neiberg, RH, et al, One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study. factors associated with success,. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(4):713–722.