http://evolve.elsevier.com/McCuistion/pharmacology

Nutrients are substances that nourish and aid in the development of the body. Nutrients provide energy, promote growth and development, and regulate body processes. Inadequate nutrient intake can cause malnutrition. Patients experiencing chronic or critical illnesses that result in surgery or hospitalization are at risk for malnutrition. Without adequate nutritional support, the body’s metabolic processes slow down or stop. This can greatly diminish organ functioning and have a poor response on the patient’s immune system.

The length of time a person may survive without nutrients is influenced by body weight and composition, genetics, health, and hydration. Patients who are critically ill may only tolerate a lack of nutrient support for a short period before organ failure occurs. Recovery is more rapid for patients who have experienced trauma, burns, or critical illness if nutrition is started within 24 to 48 hours of admission. Administration of enteral nutrition early on restores intestinal motility, maintains gastrointestinal (GI) function, reduces the movement of bacteria and other organisms, improves wound healing, decreases the incidence of infection, and ultimately decreases the length of the hospital stay. Early nutritional support improves the patient’s general health and produces favorable outcomes.

In addition to nutrients, both hydration and electrolyte balance must be considered. If all three are not addressed, preventable complications like constipation, urinary tract infection, and pressure ulcers can occur. The requirements for fluid balance are usually between 30 and 35 mL/kg/day. A healthy person requires 2000 calories per day; critically ill patients require 50% more than the normal energy requirement (approximately 3000 calories per day). If a patient has a 10% weight loss within the last 3 to 6 months and has had little or no nutrition for more than 5 days, nutritional supplementation should be considered. Nutrition and hydration are essential components necessary for everyday life.

Different Types of Nutritional Support

Oral Feeding

Many patients require nutritional supplementation due to malnutrition or anorexia (e.g., a deficiency of certain nutrients, vitamins, or minerals). Many factors can affect appetite: psychological stress about a patient’s illness and problems with family, finances, and employment are just a few of the many challenges a patient may experience. If the patient can swallow and has a working GI tract, oral nutritional supplementation between meals can help increase caloric intake. Many commercially available products can be used to supplement intake. These are marketed as puddings, bars, and supplemental nutritional drinks.

Enteral Nutrition

Enteral nutrition (EN) involves the delivery of nutrition or fluid via a tube into the GI tract, which requires a functional, accessible GI tract. Depending on the different pathologies present, EN may be used for short-term nutritional supplementation, such as with reduced appetite or swallowing difficulties, or long-term nutritional supplementation for malabsorption disorders or increased catabolism.

Routes for Enteral Feedings

A multidisciplinary team approach is used when a decision is required in regard to which feeding route to use. Many factors are considered: the patient’s condition, preferences, the length of the feeding, physiologic conditions, tolerance, and the integrity of the patient’s GI tract.

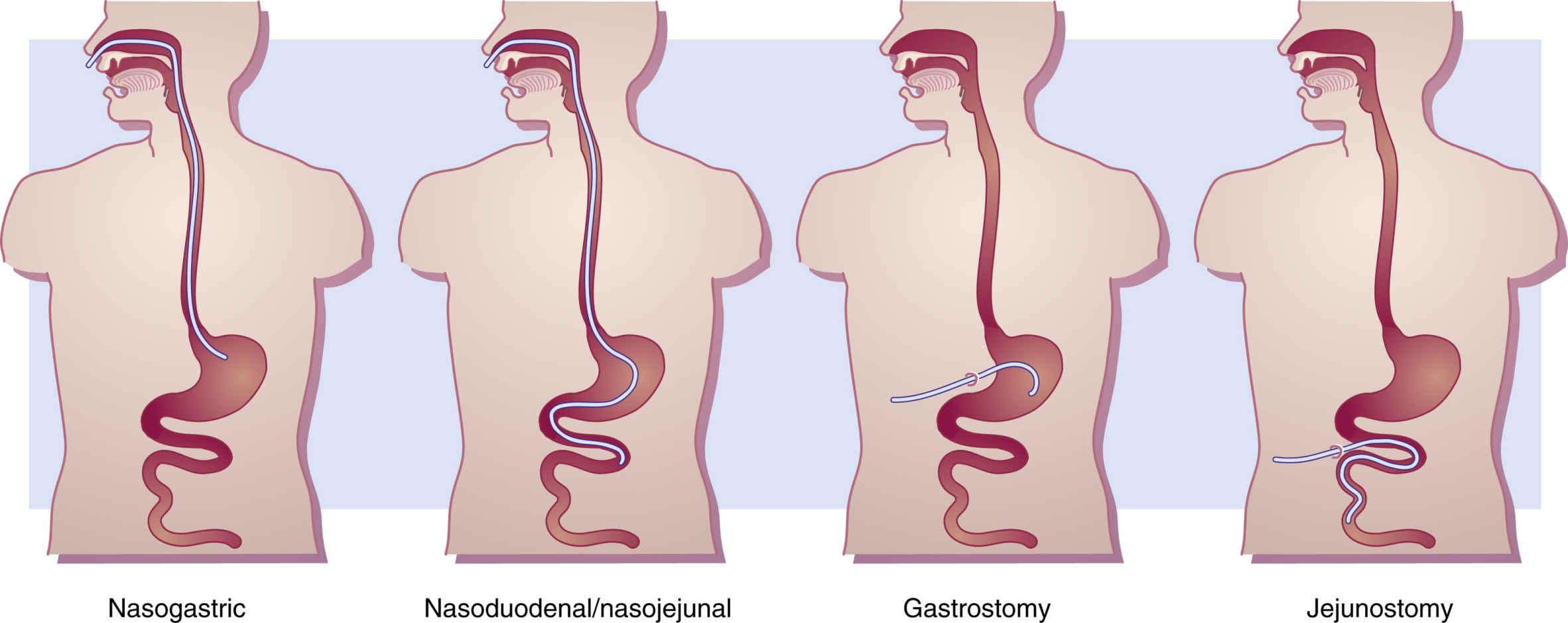

The gastrointestinal routes used for enteral tube feedings are the nasogastric, nasoduodenal/nasojejunal, gastrostomy or jejunostomy routes (Fig. 14.1). The nasogastric and gastrostomy routes deliver food directly to the stomach. The nasoduodenal/nasojejunal and the jejunostomy routes deliver food after the stomach or below the pyloric sphincter and are used for patients at risk for aspiration. These gastrointestinal routes deliver food by a tube inserted through the nose (nasogastric, nasoduodenal/nasojejunal) or directly into the GI tract (gastrostomy or jejunostomy) through the abdominal wall. The nasogastric, nasoduodenal, and nasojejunal routes are for short-term nutrition of less than 4 weeks’ duration. If long-term nutrition is required, the patient may receive a gastrostomy or a jejunostomy tube placed in the stomach or small bowel by a surgical, endoscopic, or fluoroscopic procedure.

The gastrointestinal tubes are small in diameter, are made of urethane or silicone, and are flexible and long. They are radiopaque, which makes their position easy to identify by x-ray. These tubes easily clog, especially when using thick feedings and when the patient’s medications are crushed and put down the tube. Always flush the tube before and after medication administration and when determining residual volume, so the tube remains patent and does not clog. If the tube becomes clogged, a new tube may have to be placed, which results in extra discomfort to the patient. It is important to note that these tubes can become dislodged, knotted, or kinked during patient coughing or vomiting. The gastrostomy tube, also known as the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube and the jejunostomy (J) tube are placed surgically, endoscopically, or radiologically. With the PEG tube, the patient must have an intact GI system. For patients with chronic reflux, a J-tube is placed either endoscopically or with laparoscopic surgery. Usually, the doctor orders intravenous (IV) antibiotics to decrease the risk of infection. After placement, always check your facility’s policy prior to initiating the tube feeding and use correct nursing procedure when putting medication and food through the tubes. Before the initial feeding, the policy in most facilities is to confirm correct placement of the tube with an x-ray.

Enteral Solutions

Many different types of enteral formulas are used for enteral feedings. These solutions differ according to their various nutrients, caloric values, and osmolality. The four groups of enteral solutions are (1) polymeric (milk-based, blenderized foods and commercially prepared whole nutrient formulas); (2) modular formulas (protein, glucose, polymers, and lipids); (3) elemental/monomeric formulas (predigested nutrients that are easier to absorb); and (4) specialty formulas designed to meet specific nutritional needs in certain illnesses such as liver failure, pulmonary disease, or HIV infection (Table 14.1). Some of the components of enteral solutions include (1) carbohydrates in the form of dextrose, sucrose, lactose, starch, or dextrin (the first three are simple sugars that are absorbed quickly); (2) protein in the form of intact or hydrolyzed proteins or free amino acids; and (3) fat in the form of corn, soybean, or safflower oil (some have a higher oil content than others). With all EN, sufficient water is needed to maintain hydration.

FIG. 14.1 Types of Gastrointestinal Tubes Used for Enteral Feedings.

A nasogastric tube is passed from the nose into the stomach. A weighted nasoduodenal/nasojejunal tube is passed through the nose into the duodenum/jejunum. A gastrostomy tube is introduced through a temporary or permanent opening on the abdominal wall (stoma) into the stomach. A jejunostomy tube is passed through a stoma directly into the jejunum.

Methods for Delivery

Enteral feedings are given by continuous infusion pump, intermittent infusion by gravity, intermittent bolus by syringe, and cyclic feedings by infusion pump. Continuous feedings are prescribed for the critically ill and for those who receive feedings into the small intestine. The enteral feedings are given by an infusion pump such as the Kangaroo pump, which is set to control the flow at a slow rate over 24 hours. Intermittent enteral feedings are administered every 3 to 6 hours over 30 to 60 minutes by gravity drip or infusion pump. At each feeding, 300 to 400 mL of solution is administered. Intermittent infusion is considered an inexpensive method for administering EN. The bolus method was the first method used to deliver enteral feedings, and with this method, 250 to 400 mL of solution is rapidly administered through a syringe into the tube four to six times a day. This method takes about 15 minutes each feeding, but it may not be tolerated well by the patient because a massive volume of solution is given in a short period. The bolus method may cause nausea, vomiting, aspiration, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea; a healthy patient can normally tolerate the rapidly infused solution, therefore this method is reserved for ambulatory patients. The cyclic method is another type of continuous feeding infused over 8 to 16 hours daily (day or night). Administration during daytime hours is suggested for patients who are restless or for those who have a greater risk for aspiration. The nighttime schedule allows more freedom during the day for patients who are ambulatory.

Complications

Dehydration can occur in patients receiving enteral nutrition. Diarrhea is a common complication that can lead to dehydration. High-protein formulas can also cause dehydration, and hyperosmolar solutions can draw water out of the cells in an attempt to maintain serum isoosmolality. Fluid intake is monitored, and if appropriate, fluid is added to the patient’s daily regimen of feedings. Unless contraindicated, it is recommended that 30 to 35 mL/kg/day be maintained for fluid balance in most patients.

Aspiration pneumonitis is one of the most serious and potentially life-threatening complications of tube feedings. It can occur when the contents of the tube feeding enter the patient’s lungs from the GI tract. Consequences range from coughing and wheezing to infection, tissue necrosis, and respiratory failure. An important nursing intervention is to check the agency’s policy for specific guidelines prior to initiating EN. It is imperative that the nurse check for gastric residual by gently aspirating the stomach contents before initiating enteral feeding and thereafter every 4 hours between feedings. Usually, if the residual is greater than 150 mL (check the agency policy), the nurse holds the feeding, and the residual is checked again in 1 hour. If the residual still exceeds this amount, the provider is notified. Large residuals mean the patient may have an obstruction or a problem that is important to correct prior to continuing the feeding.

Another common problem of enteral feeding is diarrhea. Rapid administration of feedings, contamination of the formula, low-fiber formulas, tube movement, and various drugs can all cause diarrhea. Check for drugs that can cause diarrhea; these may be antibiotics or sorbitol in liquid medications. Diarrhea can usually be managed or corrected by decreasing the rate of infusion, diluting the solution with water, changing the solution, discontinuing the drug, increasing the patient’s daily water intake, or administering an enteral solution that contains fiber. Constipation is another common problem that frequently occurs. It can be easily corrected by changing the formula, increasing water, or requesting a laxative.

Patients who have a long history of poor caloric intake are at risk for refeeding syndrome, which describes a cascade of metabolic and electrolyte imbalances that occur as a result of feeding a patient who is nutritionally starved for a prolonged period. Long-term undernutrition causes loss of electrolytes, vitamins, and minerals; this affects biologic processes and organ systems and can lead to abnormally low serum levels of potassium, phosphate, and magnesium that can result in cardiac arrhythmias, respiratory distress, and death. When a malnourished patient is overfed, physiologic burdens occur that put demands on cellular function and body organs. Prevention of refeeding syndrome involves ensuring that feeding begins slowly, at calorie levels below maintenance needs, and is gradually advanced.

Monitoring is essential when the patient is receiving EN. Recommended parameters to monitor include blood chemistry, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and electrolytes; glucose; triglycerides; serum proteins; intake and output; and weight. Frequency of monitoring is patient dependent and should be implemented during the entire EN process.

Enteral Safety

The nurse has an important role in administering tube feedings safely. Some of the important safety concerns are patient position, aspiration risk, residual volumes, and tube position. The head of the bed should be elevated to 30 to 45 degrees during the feeding, and if intermittent, keep the head of the bed elevated for 30 to 60 minutes after the feeding. By elevating the head of the bed, the risk of aspiration is decreased. Ensure the patient has audible bowel sounds by performing a GI assessment with auscultation. This ensures a working GI tract. Always check the gastric residual volume prior to initiating tube feedings and every 4 to 6 hours if the feedings are continuous. Always confirm the position of newly inserted tubing before beginning the first feeding. Initially, after the tube is placed, most agencies require an x-ray to confirm placement. Always follow the agency’s policy and procedure for initial confirmation of placement. Prior to each enteral feeding, placement should be confirmed to ensure the tubing has not moved and is still in the GI tract. Some agencies require pH testing of gastric secretions, whereas others recommend listening for gurgling sounds after inserting air into the tubing. Each of these measures has limitations, so more than one bedside test may be used for confirmation. Always check the agency guidelines. Electromagnetic tracking devices are being associated with reduced tube misplacement, although this technique is still new and is not available to everyone.

The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) works to improve the quality of nutrition through its guidelines and standards. ASPEN advocates for high-priority issues about nutrition. They work in conjunction with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to improve funding and education in the field of enteral and parenteral nutrition. ASPEN was first to issue guidelines, in 2002, for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in adults and pediatric populations, and it continues to update, educate, and monitor use of safe practices. Another agency that advocates for safety in both enteral and parenteral nutrition is the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which dedicates itself to the practice of health care in society and provides guidance and quality standards for public health care issues that include but are not limited to enteral and parenteral nutrition. NICE set the standard that all patients should be screened for malnutrition and treated by a multidisciplinary team of health care professionals. It also stipulates that patients and caregivers should be given adequate training for self-care if they so desire.

The Joint Commission (2014) issued an alert on the seriousness of tube misconnections, which can result in severe injury or death to the patient. One situation involved a feeding administration tube that was inadvertently connected to a tracheostomy tube, which caused serious harm to the patient. It is most important to trace all lines from the site of origin back to the patient to avoid dislodgement and misconnection errors.

Enteral Medications

Many mistakes can occur during enteral tube feedings. These mistakes are often the result of administering drugs that are incompatible with administration through a tube, failure to prepare the drug properly, and use of faulty techniques. These problems can result in an occluded feeding tube, reduced drug effect, or drug toxicity and can cause patient harm or death.

When administering nonliquid drugs through an enteral tube, the nurse should always ensure that the drug is crushable. (For a current and complete listing of drugs that should not be crushed, see http://www.ismp.org/tools/donotcrush.pdf or consult with a pharmacist.) Also, validate with the pharmacist that the drug will dissolve in water and that it can be absorbed through the enteral route. Drugs that cannot be dissolved are timed-release, enteric-coated, and sublingual forms and bulk-forming laxatives; these medications should not be crushed. Prepare each medication separately so that the medication is identifiable up until the time of delivery. Open capsules separately and check with the pharmacist about whether the capsule contents can be crushed. Crush the solid dosage forms after ensuring the medications are crushable, and dissolve each medication separately in about 15 mL of water. The drug must be in liquid form or dissolved in water prior to administration through enteral tubing. Properly dilute liquid medication with water when administering it through the feeding tube. Never mix medications with feeding formulas. Prior to and after the drug is administered, flush with about 15 mL of water. Proper flushing ensures that the drug has been delivered and the tube is clear. Once the tube has been flushed, the feeding can be restarted after the drug is given.

Many drugs can be given to patients who require tube feeding to aid in absorption and digestion and to promote gastric emptying; these include pancreatic enzymes, probiotics, antiemetics, proton pump inhibitors, and drugs to prevent gastric ulcers.

It is essential to know the importance of temporarily stopping the infusion when certain types of drugs are administered. Some medications require that the feeding be stopped for as long as 30 minutes to allow for adequate absorption.

Evaluation

• Determine that the patient is receiving the prescribed nutrients daily and is free of complications associated with enteral feedings.

Parenteral Nutrition

The terms parenteral nutrition (PN), total parenteral nutrition (TPN), and hyperalimentation (HA) are used synonymously. PN is the administration of nutrients by a route other than the GI tract (e.g., the bloodstream). If a patient is not eligible for EN because of a nonfunctioning GI tract or intestinal failure, PN is delivered intravenously. The word “total” suggests that the patient is receiving all of the required nutrients, fluid, and electrolyte requirements in the bag. In some circumstances, PN and EN may be given concurrently. The delivery of both EN and PN is used when the GI tract is partially functioning or if the patient is being weaned off of PN. Parenteral nutrition has many risks, so the option of EN should be fully explored before starting PN. Suggested indications for patients who require PN are those with bowel obstruction, prolonged paralytic ileus, inflammatory bowel disease, or severe pancreatitis, and those who require bowel rest following complex GI surgery. Also, patients with greater nutritional needs sometimes require PN, such as those who have sustained severe trauma or burns and the severely malnourished.

Solutions for parenteral nutrition include amino acids, carbohydrates, electrolytes, fats, trace elements, vitamins, and water. PN is individualized according to the patient’s general health needs. Each element of the prescription can be manipulated according to changes in the patient’s clinical requirements. The entire process requires a multidisciplinary team approach that involves the nurse, nutritionist, and pharmacist with the patient’s provider leading the care team. Commercially prepared PN base solutions are available and contain dextrose and protein in the form of amino acids. The pharmacist can add prescribed electrolytes, vitamins, and trace elements to customize the solution to meet the patient’s needs. Calories are provided by carbohydrates in the form of dextrose and by fat in the form of fat emulsion. Carbohydrates provide 60% to 70% of calorie (energy) needs. Amino acids (proteins) provide about 3.5% to 20% of a patient’s energy needs. PN has a high glucose concentration. Fat emulsion (lipid) therapy provides an increased number of calories, usually 30%, and is a carrier of fat-soluble vitamins. The recommended energy intake is 25 to 35 cal/kg/day in a nonobese patient. Solutions differ for pediatric patients, who have varied fluid needs and require more energy per kilogram.

High glucose concentrations are irritating to peripheral veins, so PN is administered through either a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) via the cephalic or basilica vein, or a central venous catheter via the subclavian or internal jugular vein; this depends on the tonicity of the concentration. The rapid blood flow of the central veins allows placement of the catheter in the vena cava, which has the greatest blood flow of any vein in the body and reduces the risk of thrombophlebitis. If the treatment is used for short-term therapy (<4 weeks), a PICC line is inserted. If the treatment will last longer than 4 weeks, a central line catheter is placed. PN must always be administered by an infusion pump to allow for an accurate flow rate. PN enhances wound healing and provides the necessary nutrients to prevent cellular catabolism. Policies and procedures for PN therapy may vary by region and facility and must be researched and followed accordingly.

Complications

Complications associated with PN can result from catheter insertion and PN infusion. See Table 14.2 for a list of PN complications.

Air embolism occurs when air enters into the central line catheter system. To prevent air embolism during dressing, cap, and tubing changes, ask the patient to turn his or her head in the opposite direction of the insertion site and to take a deep breath, hold it, and bear down. This is called the Valsalva maneuver, and it will increase intrathoracic venous pressure while preventing the risk of air embolism. Always keep the clamp on the central line tubing closed except when in use.

Use strict aseptic technique when changing IV tubing and dressings at the insertion site. PN solution has a high concentration of glucose and is an excellent medium for bacterial growth. Monitor the patient’s temperature closely, and if fever occurs, suspect sepsis. Always follow the facility’s policy for the correct protocol in changing the PN solutions (12 to 24 hours), IV tubing (24 hours), and central line dressing (48 hours). Keep the prepared PN solutions refrigerated, and administer the full amount within the designated time according to the agency’s policy.

Hyperglycemia occurs primarily as a result of the hypertonic dextrose solution, but it also occurs when the infusion rate for PN is too rapid. In some cases, the pharmacist can add insulin to the PN solution if ordered by the provider. Assess the patient carefully for glucose intolerance. The infusion is started at a slow rate of 40 to 60 mL/hour as prescribed. Monitor the patient’s blood glucose level every 4 to 6 hours until stable and then every 24 hours or according to the facility’s policy. Many providers will order sliding-scale insulin for their patients receiving PN.

The sudden interruption of PN therapy can cause hypoglycemia, therefore it is wise to keep a bag of 10% dextrose in the patient’s room. In the event that the next bag of PN is late in arriving from the pharmacy, the bag of dextrose can be hung to avoid hypoglycemia. Gradually decrease the infusion rate when PN is discontinued, and monitor the patient’s blood glucose level.

Evaluation

• Evaluate the patient’s positive and negative response to PN therapy.

• Determine periodically whether the patient’s serum electrolytes, protein, and glucose levels are within desired ranges.

• Evaluate nutritional status by weight changes, energy level, feelings of well-being, symptom control, and healing.

• Evaluate patient and family understanding of the purpose and possible complications of PN therapy.

Critical Thinking Case Study

BD experienced trauma after being involved in an automobile accident. She has been in the intensive care unit for 5 days and is unable to eat. BD experienced compression of her abdomen and will need gastrointestinal (GI) exploratory surgery. BD is receiving D5 0.45% sodium chloride (NaCl). Her sodium (Na+) level is 125 mEq/L, potassium (K+) level is 3.1 mEq/L, glucose is 70 mg/dL, magnesium is 2.0 mEq/L, and phosphorus is 3.0 mg/dL.

1. Will BD receive enteral or parenteral nutrition and why?

2. After a review of BD’s labs, which electrolytes do you expect to see the provider order in the parenteral nutrition (PN) bag?

3. BD will need central line placement. What complications will you assess BD for after the insertion of the central line and during the parenteral infusion?

4. The PN has been infusing without any problems, and BD seems to be tolerating it well. You notice 200 mL of the PN is left in the bag after it has been infusing for 24 hours. What is the best nursing response?

5. Describe nursing interventions related to PN.