Objectives

Implications of Undernutrition for the Sick or Stressed Patient

![]()

Be sure to check out the bonus material, including free self-assessment exercises, on the Evolve web site at

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Urden/priorities/.

Although illness or injury is the major factor contributing to development of malnutrition, other possible contributing factors are lack of communication among the nurses, physicians, and dietitians responsible for the care of these patients; frequent diagnostic testing and procedures, which lead to interruption in feeding; medications and other therapies that cause anorexia, nausea, or vomiting and thereby interfere with food intake; insufficient monitoring of nutrient intake; and inadequate use of supplements, tube feedings, or total parenteral nutrition (TPN) to maintain the nutritional status of these patients.

Nutritional status tends to deteriorate during hospitalization unless appropriate nutrition support is started early and continually reassessed. Malnutrition in hospitalized patients is associated with a wide variety of adverse outcomes. Wound dehiscence, pressure ulcers, sepsis, infections, respiratory failure requiring ventilation, longer hospital stays, and death are more common among malnourished patients.1–3 Decline in nutritional status during hospitalization is associated with higher incidences of complications, increased mortality rates, increased length of stay, and higher hospital costs.

Assessing Nutritional Status

A nutrition screening should be conducted on every patient. A brief questionnaire to be completed by the patient or significant other, the nursing admission form, or the physician’s admission note usually provides enough information to determine whether the patient is at nutritional risk (Box 6-1). Any patient judged to be nutritionally at risk needs a more thorough nutrition assessment.

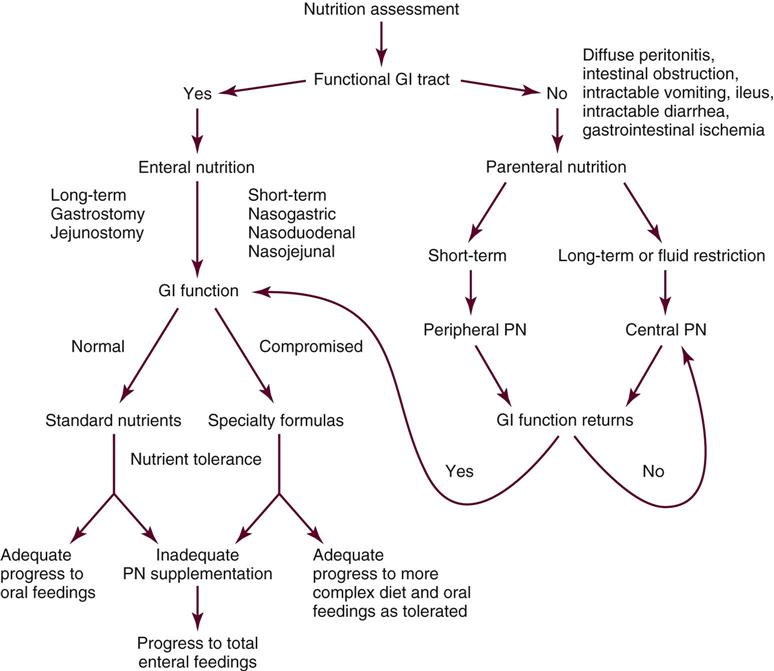

Nutrition support is the provision of specially formulated or delivered oral, enteral, or parenteral nutrients to maintain or restore optimal nutrition status.4 The nutrition assessment can be performed by or under the supervision of a registered dietitian or by a nutrition care specialist (e.g., nurse with specialized expertise in nutrition). Figure 6-1 shows the route of administration of specialized nutrition support.

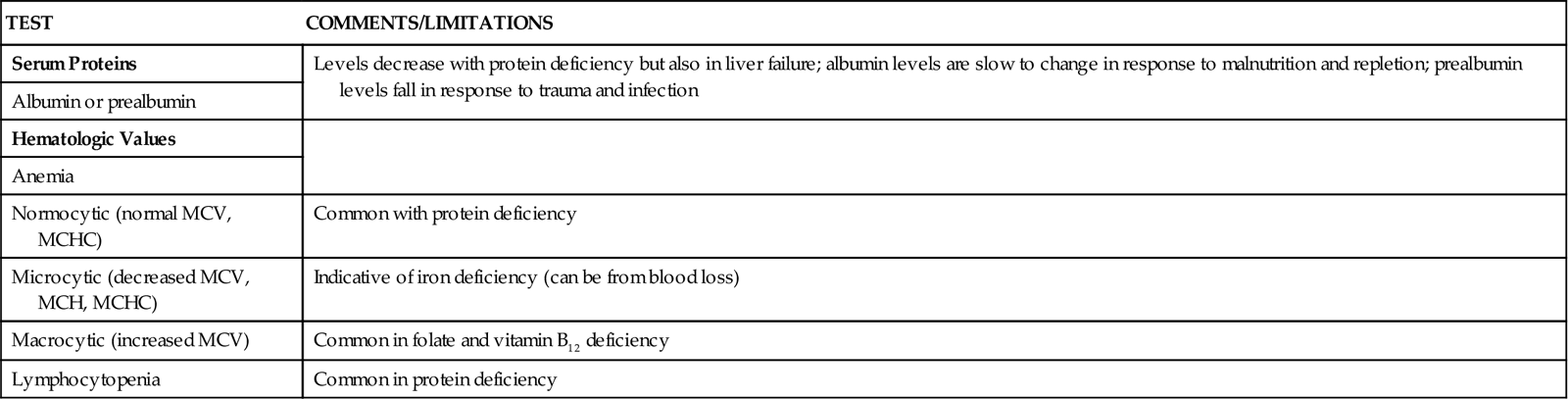

Biochemical Data

A wide range of laboratory tests can provide information about nutritional status. Those most often used in the clinical setting are described in Table 6-1. No diagnostic tests for evaluation of nutrition are perfect, and care must be taken in interpreting the results of the tests.5

TABLE 6-1

COMMON BLOOD AND URINE TESTS USED IN NUTRITION ASSESSMENT

| TEST | COMMENTS/LIMITATIONS |

| Serum Proteins | Levels decrease with protein deficiency but also in liver failure; albumin levels are slow to change in response to malnutrition and repletion; prealbumin levels fall in response to trauma and infection |

| Albumin or prealbumin | |

| Hematologic Values | |

| Anemia | |

| Normocytic (normal MCV, MCHC) | Common with protein deficiency |

| Microcytic (decreased MCV, MCH, MCHC) | Indicative of iron deficiency (can be from blood loss) |

| Macrocytic (increased MCV) | Common in folate and vitamin B12 deficiency |

| Lymphocytopenia | Common in protein deficiency |

Clinical or Physical Manifestations

A thorough physical examination is an essential part of nutrition assessment. Box 6-2 lists some of the more common findings that may indicate an altered nutritional state. It is especially important for the nurse to check for signs of muscle wasting, loss of subcutaneous fat, skin or hair changes, and impairment of wound healing.

Diet and Health History

Information about dietary intake and significant variations in weight is a vital part of the history. Dietary intake can be evaluated in several ways, including a diet record, a 24-hour recall, and a diet history. Other information to include in a nutrition history is listed in Box 6-3.

Evaluating Nutrition Assessment Findings

It is rare for a patient to exhibit a lack of only one nutrient. Nutritional deficiencies usually are combined, with the patient lacking adequate amounts of protein, calories, and possibly vitamins and minerals. A common form of combined nutritional deficit among hospitalized patients is protein calorie malnutrition (PCM). Two types of PCM are kwashiorkor and marasmus.

Kwashiorkor results in low levels of the serum proteins albumin, transferrin, and prealbumin; low total lymphocyte count; impaired immunity; loss of hair or hair pigment; edema resulting from low plasma oncotic pressure caused by a loss of plasma proteins; and an enlarged, fatty liver. Marasmus is recognizable by weight loss, loss of subcutaneous fat, and muscle wasting. In the marasmic person, creatinine excretion in the urine is low, an indication of reduced muscle mass. Because PCM weakens muscles, increases vulnerability to infection, and can prolong hospital stays, the health care team should diagnose this serious disorder as quickly as possible so that an appropriate nutrition intervention can be implemented.

Determining Nutritional Needs

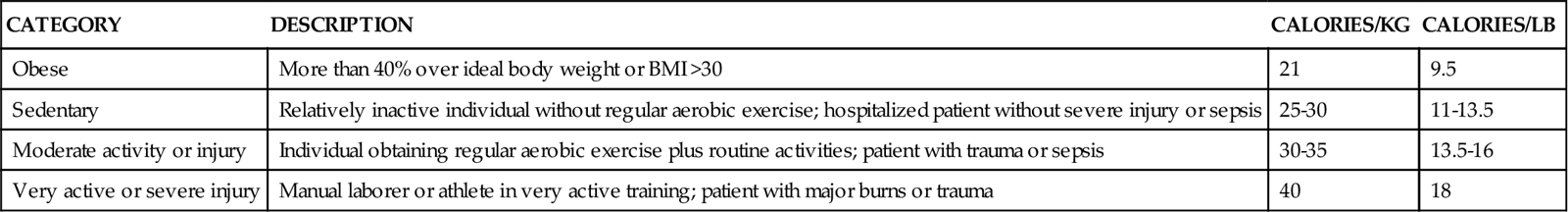

Calorie and protein needs of patients are often estimated using formulas that provide allowances for increased nutrient use associated with injury and healing. Although indirect calorimetry is considered the most accurate method to determine energy expenditure, estimates using formulas have demonstrated reasonable accuracy.6,7 Some rules of thumb are available to provide a rough estimate of caloric needs so that nurses and other caregivers can quickly determine if patients are being seriously overfed or underfed (Table 6-2).

TABLE 6-2

| CATEGORY | DESCRIPTION | CALORIES/KG | CALORIES/LB |

| Obese | More than 40% over ideal body weight or BMI >30 | 21 | 9.5 |

| Sedentary | Relatively inactive individual without regular aerobic exercise; hospitalized patient without severe injury or sepsis | 25-30 | 11-13.5 |

| Moderate activity or injury | Individual obtaining regular aerobic exercise plus routine activities; patient with trauma or sepsis | 30-35 | 13.5-16 |

| Very active or severe injury | Manual laborer or athlete in very active training; patient with major burns or trauma | 40 | 18 |

The goal of nutrition assessment is to obtain the most accurate estimate of nutritional requirements. Underfeeding and overfeeding must be avoided during critical illness. Overfeeding results in excessive production of carbon dioxide, which can be a burden in the person with pulmonary compromise. Overfeeding increases fat stores, which can contribute to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia. Hyperglycemia increases the risk of postoperative infections in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals.8–10 Hyperglycemia is a complication to be avoided if possible.

Nutrition and Cardiovascular Alterations

Diet and cardiovascular disease may interact in a variety of ways. On the one hand, excessive nutrient intake, manifested by overweight or obesity and a diet rich in cholesterol and saturated fat, is a risk factor for development of arteriosclerotic heart disease. On the other hand, the consequences of chronic myocardial insufficiency may include malnutrition.

Nutrition Assessment in Cardiovascular Alterations

A nutrition assessment provides the nurse and other members of the health care team the information necessary to plan the patient’s nutrition care and education. Common findings in the nutrition assessment of the cardiovascular patient are summarized in Box 6-4. The major nutritional concerns relate to appropriateness of body weight and the levels of serum lipids and blood pressure.

Nutrition Intervention in Cardiovascular Alterations

Myocardial Infarction

The following guidelines will assist the nurse in providing appropriate nutritional care for the patient in the immediate post-myocardial infarction period:

Hypertension

A substantial number of individuals with hypertension are “salt sensitive,” with their disorder improving when sodium intake is limited. Therefore restriction of sodium intake, usually to 2.5 g/day or less, is often advised to help control hypertension.11 One teaspoon of salt provides about 2.3 g of sodium. Most salt substitutes contain potassium chloride and may be used with the physician’s approval by the patient who has no renal impairment. A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products (the DASH, or Dietary Approaches to Stopping Hypertension, diet) combined with a sodium restriction is often more effective than sodium restriction alone.12

Heart Failure

Nutrition intervention for the patient with heart failure is designed to reduce fluid retained within the body and thus reduce the preload. Because fluid accompanies sodium, limitation of sodium is necessary to reduce fluid retention. Specific interventions include limiting salt intake, usually to 5 g/day or less, and limiting fluid intake as appropriate. If fluid is restricted, the daily fluid allowance is usually 1.5 to 2 L/day, to include both fluids in the diet and those given with medications and for other purposes.

Cardiac Cachexia

The severely malnourished cardiac patient often develops heart failure. Therefore sodium and fluid restriction, as previously described, is appropriate. It is important to concentrate nutrients into as small a volume as possible and to serve small amounts frequently, rather than three large meals daily. The individual should be encouraged to consume calorie-dense foods and supplements. Good choices include meats and poultry, cheeses, yogurt, frozen yogurt, and ice cream.

Because the patient is likely to tire quickly and to suffer from anorexia, enteral tube feeding may be necessary. Typical tube feeding formulas provide 1 calorie per milliliter (cal/ml), but more concentrated products are available to provide adequate nutrients in a smaller volume. The nurse must monitor the fluid status of these patients carefully when they are receiving nutrition support. Assessing breath sounds and observing for presence and severity of peripheral edema and changes in body weight are performed daily or more frequently. A consistent weight gain of more than 0.11 to 0.22 kg (0.25 to 0.5 lb) per day usually indicates fluid retention rather than gain of fat and muscle mass.

Nutrition and Pulmonary Alterations

Malnutrition has extremely adverse effects on respiratory function, decreasing surfactant production, diaphragmatic mass, vital capacity, and immunocompetence. Patients with acute respiratory disorders find it difficult to consume adequate oral nutrients and can rapidly become malnourished. Individuals who have an acute illness superimposed on chronic respiratory problems are also at high risk. Almost three fourths of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have had weight loss. Patients with undernutrition and end-stage COPD, however, often cannot tolerate the increase in metabolic demand that occurs during refeeding. In addition, they are at significant risk for development of cor pulmonale and may fail to tolerate the fluid required for delivery of enteral or parenteral nutrition support. Prevention of severe nutritional deficits, rather than correction of deficits once they have occurred, is important in nutritional management of these patients.

Nutrition Assessment in Pulmonary Alterations

Common findings in nutrition assessment related to pulmonary alterations are summarized in Box 6-5. The patient with respiratory compromise is especially vulnerable to the effects of fluid volume excess and must be assessed continually for this complication, particularly during enteral and parenteral feeding.

Nutrition Intervention in Pulmonary Alterations

Prevent or Correct Undernutrition/Underweight

The nurse and dietitian work together to encourage oral intake in the undernourished or potentially undernourished patient who is capable of eating. Small, frequent feedings are especially important because a very full stomach can interfere with diaphragmatic movement. Mouth care should be provided before meals and snacks to clear the palate of the taste of sputum and medications. Administering bronchodilators with food can help to reduce the gastric irritation caused by these medications.

Because of anorexia, dyspnea, debilitation, or need for ventilatory support, however, many patients will require enteral tube feeding or TPN. It is especially important for the nurse to be alert to the risk of pulmonary aspiration in the patient with an artificial airway. To reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration during enteral tube feeding, the nurse should (1) keep the patient’s head elevated at least 45 degrees during feedings, unless contraindicated; (2) discontinue feedings 30 to 60 minutes before any procedures that require lowering the head; (3) keep the cuff of the artificial airway inflated during feeding, if possible; (4) monitor the patient for increasing abdominal distention; and (5) check tube placement before each feeding (if intermittent) or at least every 4 to 8 hours if feedings are continuous.

Avoid Overfeeding

Overfeeding increases the production of carbon dioxide (CO2). This is unlikely to be significant in the patient who is eating foods. Instead, it is an iatrogenic complication of TPN or enteral feeding. Arterial CO2 tension (PaCO2) may rise sufficiently to make it difficult to wean a patient from the ventilator. A balanced regimen with both lipids and carbohydrates providing the nonprotein calories is optimal for the patient with respiratory compromise, and the patient needs to be reassessed continually to ensure that caloric intake is not excessive.

Prevent Fluid Volume Excess

Pulmonary edema and failure of the right side of the heart, which may be precipitated by fluid volume excess, further worsen the status of the patient with respiratory compromise. Maintaining careful intake and output records allows for accurate assessment of fluid balance. Usually the patient requires no more than 35 to 40 ml/kg/day of fluid. For the patient receiving nutrition support, fluid intake can be reduced by (1) using 20% or 30% lipid emulsions as a source of calories, (2) using tube feeding formulas providing at least 2 cal/ml (the dietitian can recommend appropriate formulas), and (3) choosing oral supplements that are low in fluid.

Nutrition and Neurologic Alterations

Because neurological disorders such as stroke and closed head injury tend to be long-term problems, these patients require good nutritional care to prevent nutritional deficits and promote well-being.

Nutrition Assessment in Neurological Alterations

Nutrition-related assessment findings vary widely in the patient with neurological alterations, depending on the type of disorder present (Box 6-6).

Nutrition Intervention in Neurological Alterations: Prevent or Correct Nutrition Deficits

Oral Feedings

Patients with dysphagia or weakness of the swallowing musculature often experience the greatest difficulty in swallowing dry foods and thin liquids (e.g., water) that are difficult to control.

Tube Feedings and Total Parenteral Nutrition

Patients who are unconscious or unable to eat because of severe dysphagia, weakness, ileus, or other reasons require tube feedings or TPN. Prompt initiation of nutrition support must be a priority in the patient with neurological impairment. Needs for protein and calories are increased by infection and fever, as in the patient with encephalitis or meningitis. Needs for protein, calories, zinc, and vitamin C are increased during wound healing, as in trauma patients and those with pressure ulcers.

Patients with neurological deficits have an increased risk of certain complications (particularly pulmonary aspiration) during tube feeding and therefore require especially careful nursing management. Patients of most concern are (1) those with an impaired gag reflex, such as some patients with cerebrovascular accident (stroke); (2) those with delayed gastric emptying, such as patients in the early period after spinal cord injury and patients with head injury treated with barbiturate coma; and (3) those likely to experience seizures. To help prevent pulmonary aspiration, the patient’s head is kept elevated, if not contraindicated; when elevation of the head is not possible, administering feedings with the patient in the prone or lateral position will allow free drainage of emesis from the mouth and decrease the risk of aspiration.

Administering phenytoin with enteral formulas decreases the absorption of the drug and the peak serum level achieved and thus may increase the risk of seizures. The phenytoin dosage must be adjusted appropriately. Phenytoin levels should be monitored carefully in patients receiving enteral feedings.13

Hyperglycemia is a common complication in patients receiving corticosteroids. Regular monitoring of blood glucose is an important part of their care. They may require insulin to control the hyperglycemia.

Prompt use of nutrition support is especially important for patients with head injuries because head injury causes marked catabolism, even in patients who receive barbiturates, which should decrease metabolic demands. Head-injured patients rapidly exhaust glycogen stores and begin to use body proteins to meet energy needs, a process that can quickly lead to PCM. The catabolic response is partly a result of corticosteroid therapy in head-injured patients. However, the hypermetabolism and hypercatabolism are also caused by dramatic hormonal responses to this type of injury.14 Levels of cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine increase as much as seven times normal. These hormones increase the metabolic rate and caloric demands, causing mobilization of body fat and proteins to meet the increased energy needs. Furthermore, head-injured patients undergo an inflammatory response and may be febrile, creating increased needs for protein and calories. Improvement in outcome and reduction in complications have been observed in head-injured patients who receive adequate nutrition support early in the hospital course.15

Nutrition and Renal Alterations

Providing adequate nutrition care for the patient with renal disease can be extremely challenging. Although renal disturbances and their treatments can greatly increase needs for nutrients, necessary restrictions in intake of fluid, protein, phosphorus, and potassium make delivery of adequate calories, vitamins, and minerals difficult. Thorough nutrition assessment provides the basis for successful nutrition management in patients with renal disease.

Nutrition Assessment in Renal Alterations

Some common assessment findings in individuals with renal disease are listed in Box 6-7.

Nutrition Intervention in Renal Alterations

The goal of nutrition intervention is to administer adequate nutrients, including calories, protein, vitamins, and minerals, while avoiding excesses of protein, fluid, electrolytes, and other nutrients with potential toxicity.

Protein

The kidney is responsible for excreting nitrogen from amino acids or proteins in the form of urea. Thus, when urinary excretion of urea is impaired in renal failure, blood levels of urea rise. Excessive protein intake may worsen uremia. However, the patient with renal failure often has (1) other physiological stresses that actually increase protein/amino acid needs; (2) losses from dialysis, wounds, and fistulae; (3) use of corticosteroid drugs that exert a catabolic effect; (4) increased endogenous secretion of catecholamines, corticosteroids, and glucagon, all of which can cause or aggravate catabolism; (5) metabolic acidosis, which stimulates protein breakdown; and (6) catabolic conditions (e.g., trauma, surgery, sepsis). Therefore patients with acute renal failure need adequate amounts of protein to avoid catabolism of body tissues. Approximately 1.5 to 1.7 g/kg/day has successfully maintained adequate protein nutrition in these patients.16,17

During hemodialysis and arteriovenous hemofiltration, amino acids are freely filtered and lost, but proteins such as albumin and immunoglobulin are not lost. Both proteins and amino acids are removed during peritoneal dialysis, creating a greater nutritional requirement for protein. Protein needs are estimated at approximately 1.0 to 1.2 g/kg/day for stable patients receiving hemodialysis or hemofiltration and 1.2 to 1.3 g/kg/day for those receiving peritoneal dialysis.18,19 Patients in the process of wound healing and those with ongoing protein losses have greater needs.

Fluids

The patient with renal insufficiency usually does not require a fluid restriction until urine output begins to diminish. Patients receiving hemodialysis are limited to a fluid intake resulting in a gain of no more than 0.45 kg (1 lb) per day on the days between dialysis. This generally means a daily intake of 500 to 750 ml plus the volume lost in urine. With the use of continuous peritoneal dialysis, hemofiltration, or hemodialysis, the fluid intake can be liberalized.20 This more liberal fluid allowance permits more adequate nutrient delivery, whether by oral, tube, or parenteral feedings. Enteral formulas containing 1.5 to 2.0 cal/ml or more provide a concentrated source of calories for tube-fed patients who require fluid restriction. Intravenous lipids, particularly 20% emulsions, can be used to supply concentrated calories for the TPN patient. Intradialytic TPN can be used to supply an additional source of nutrients at a time when the fluid can be rapidly removed in dialysis.21,22

Energy (Calories)

Energy needs are not increased by renal failure, but adequate calories must be provided to avoid catabolism.16 It is essential that the renal patient receive an adequate number of calories to prevent catabolism of body tissues to meet energy needs. Catabolism not only reduces the mass of muscle and other functional body tissues but also releases nitrogen that must be excreted by the kidney. Adults with renal insufficiency need about 30 to 35 cal/kg/day, compared with the 25 to 30 cal/kg/day needed by healthy adults, to prevent catabolism and ensure that all protein consumed is used for anabolism rather than to meet energy needs.19 After renal transplantation, when the patient initially receives large doses of corticosteroids, it is especially important to ensure that caloric intake is adequate (usually 25 to 35 cal/kg/day) to prevent undue catabolism.

Hypertriglyceridemia is found in a substantial number of patients with renal disorders. This condition is worsened by excessive intake of simple refined sugars, such as sucrose (table sugar) or glucose. Glucose in the peritoneal dialysate may be a significant calorie source and a contributing factor in hypertriglyceridemia. Approximately 70% of the glucose instilled during peritoneal dialysis to serve as an osmotic agent may be absorbed, and this must be considered part of the patient’s carbohydrate intake. The glucose monohydrate used in intravenous and dialysate solutions supplies 3.4 cal/g. Thus, if a patient receives 4.25% glucose (4.25 g glucose per 100 ml solution) in the dialysate, the patient receives the following:

< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mml" />

To help control hypertriglyceridemia, only about 30% to 35% of the patient’s calories should come from carbohydrates, including glucose from the dialysate, with the major portion of dietary carbohydrate coming from complex carbohydrates (starches and fibers).

Nutrition and Gastrointestinal Alterations

Because the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is so inherently related to nutrition, it is not surprising that impairment of the GI tract and its accessory organs has a major impact on nutrition. Two of the most serious GI-related illnesses seen among critical care patients are hepatic failure and pancreatitis.

Nutrition Assessment in Gastrointestinal Alterations

Common assessment findings in patients with GI disease are listed in Box 6-8.

Nutrition Intervention in Gastrointestinal Alterations

Hepatic Failure

Because the diseased liver has impaired ability to deactivate hormones, levels of circulating glucagon, epinephrine, and cortisol are elevated. These hormones promote catabolism of body tissues and cause glycogen stores to be exhausted. Release of lipids from their storage depots is accelerated, but the liver has decreased ability to metabolize them for energy. Furthermore, inadequate production of bile salts by the liver results in malabsorption of fat from the diet. Therefore body proteins are used for energy sources, producing tissue wasting.

The branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs)—leucine, isoleucine, and valine—are especially well used for energy, and their levels in the blood decline. Conversely, levels of the aromatic amino acids (AAAs)—phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan—rise as a result of tissue catabolism and impaired ability of the liver to clear them from the blood. The AAAs are precursors for neurotransmitters in the central nervous system (serotonin and dopamine). Rising levels of AAAs may alter nerve activity within the brain, leading to symptoms of encephalopathy. In addition, the damaged liver cannot clear ammonia from the circulation adequately, and ammonia accumulates in the brain. The ammonia may contribute to the encephalopathic symptoms and also to brain edema.23,24

Monitoring Fluid and Electrolyte Status.

Ascites and edema occur because of a combination of factors. There is decreased colloid osmotic pressure in the plasma, because of the reduction of production of albumin and other plasma proteins by the diseased liver, increased portal pressure caused by obstruction, and renal sodium retention from secondary hyperaldosteronism. To control the fluid retention, restriction of sodium (usually 2000 mg) and fluid (1500 ml or less daily) is generally necessary, in conjunction with administration of diuretics. Patients are weighed daily to evaluate the success of treatment. Physical status and laboratory data must be closely monitored for deficiencies of potassium, phosphorus, and vitamins A, D, E, and K, and zinc.25

Provision of a Nutritious Diet and Evaluation of Response to Dietary Protein.

PCM and nutritional deficiencies are common in hepatic failure. The causes of malnutrition are complex and usually related to decreased intake, malabsorption, maldigestion, and abnormal nutrient metabolism. Nutrition intervention is individualized and based on these metabolic changes. A diet with adequate protein helps to suppress catabolism and promote liver regeneration. Stable patients with cirrhosis usually tolerate 0.8 to 1 g protein/kg/day. Patients with severe stress or nutritional deficits have increased needs—as much as 1.2 to 2 g/kg/day.26 Aggressive treatment with medications, including lactulose, neomycin, or metronidazole, is considered first-line therapy in the management of acute hepatic encephalopathy. In a minority of patients, pharmacotherapy may not be effective, and protein restriction to as little as 0.5 g/kg/day or less may be necessary for brief periods. Chronic protein restriction is not recommended as a long-term management strategy for patients with liver disease.25,26

Anorexia may interfere with oral intake, and the nurse may need to provide much encouragement to the patient to ensure intake of an adequate diet. Prospective calorie counts may need to be instituted to provide objective evidence of oral intake. Small, frequent feedings are usually better tolerated by the anorexic patient than are three large meals daily. Soft foods are preferred because the patient may have esophageal varices that might be irritated by high-fiber foods. If patients are unable to meet their caloric needs, they may require oral supplements or enteral feeding. Small-bore nasoenteric feeding tubes can be used safely without increasing risk of variceal bleeding.26 TPN should be reserved only for patients who are absolutely unable to tolerate enteral feeding.25 Diarrhea from concurrent administration of lactulose should not be confused with feeding intolerance.

A diet adequate in calories (at least 30 cal/kg daily) is provided to help prevent catabolism and to prevent the use of dietary protein for energy needs.27 In cases of malabsorption, medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) may be used to meet caloric needs. Pancreatic enzymes may also be considered for malabsorption problems.

BCAA-enriched products have been developed for enteral and parenteral nutrition of patients with hepatic disease. These products may be used in patients with acute hepatic encephalopathy who do not tolerate standard diets or enteral formulas, or who are unresponsive to lactulose. However, no substantial evidence exists showing BCAAs are superior to standard formulas in regard to nitrogen balance or as treatment for encephalopathy.25,26 The patient who undergoes successful liver transplantation is usually able to tolerate a regular diet with few restrictions. Intake during the postoperative period must be adequate to support nutritional repletion and healing; 1 to 1.2 g protein/kg/day and approximately 30 cal/kg/day are usually sufficient. Immunosuppressant therapy (corticosteroids and cyclosporine or tacrolimus) contributes to glucose intolerance. Dietary measures to control glucose intolerance include (1) obtaining approximately 30% of dietary calories from fat, (2) emphasizing complex sources of carbohydrates, and (3) eating several small meals daily. Moderate exercise often helps to improve glucose tolerance.

Pancreatitis

The pancreas is an exocrine and endocrine gland required for normal digestion and metabolism of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats. Acute pancreatitis is an inflammatory process that occurs as a result of autodigestion of the pancreas by enzymes normally secreted by that organ. Food intake stimulates pancreatic secretion and thus increases the damage to the pancreas and the pain associated with the disorder. Patients usually present with abdominal pain and tenderness and elevations of pancreatic enzymes. A mild form of acute pancreatitis occurs in 80% of patients requiring hospitalization, and severe acute pancreatitis occurs in the other 20%.28 Patients with the mild form of acute pancreatitis do not require nutrition support and generally resume oral feeding within 7 days. Chronic pancreatitis may develop and is characterized by fibrosis of pancreatic cells. This results in loss of exocrine and endocrine function because of the destruction of acinar and islet cells. The loss of exocrine function leads to malabsorption and steatorrhea. In chronic pancreatitis, the loss of endocrine function results in impaired glucose tolerance.28

Prevention of Further Damage to the Pancreas and Preventing Nutritional Deficits.

Effective nutritional management is a key treatment for patients with acute pancreatitis or exacerbations of chronic pancreatitis. The concern that feeding may stimulate the production of digestive enzymes and perpetuate tissue damage has led to the widespread use of TPN and bowel rest. Recent data suggest that enteral nutrition infused into the distal jejunum bypasses the stimulatory effect of feeding on pancreatic secretion and is associated with fewer infectious and metabolic complications compared to TPN.29,30

The results of randomized studies comparing TPN with total enteral nutrition (TEN, or enteral tube feeding) indicate that TEN is preferable to TPN in patients with severe acute pancreatitis, reducing costs and the risk of sepsis and improving clinical outcome.29–31 Patients unable to tolerate TEN should receive TPN, and some patients may require a combination of TEN and TPN to meet nutritional requirements.32,33 Low-fat enteral formulas and those with fat provided by MCTs are more readily absorbed than formulas that are high in long-chain triglycerides (e.g., corn or sunflower oil).

When oral intake is possible, small frequent feedings of low-fat foods are least likely to cause discomfort.30 Alcohol intake should be avoided because it worsens the tissue damage and the pain associated with pancreatitis. Guidelines for treatment of diabetes (see following sections) are appropriate for the care of the person with glucose intolerance or diabetes related to pancreatitis.

Nutrition and Endocrine Alterations

Endocrine alterations have far-reaching effects on all body systems and thus affect nutritional status in a variety of ways. One of the most common endocrine problems, both in the general population and among critically ill patients, is diabetes mellitus.

Nutrition Assessment in Endocrine Alterations

Common assessment findings in individuals with endocrine alterations are listed in Box 6-9. Because of the prevalence of patients with non-insulin-dependent (type 2) diabetes mellitus among the hospitalized population, the acute nutritional problems most often noted in patients with endocrine alterations are related to glycemic control.

Nutrition Intervention in Endocrine Alterations

Nutrition Support and Blood Glucose Control

Patients with insulin-dependent (type 1) diabetes mellitus or endocrine dysfunction caused by pancreatitis often have weight loss and malnutrition as a result of tissue catabolism because they cannot use dietary carbohydrates to meet energy needs. Although patients with type 2 diabetes are more likely to be overweight than underweight, they too may become malnourished as a result of chronic or acute infections, trauma, major surgery, or other illnesses. Nutrition support should not be neglected simply because a patient is obese, because PCM develops even in these patients. When a patient is not expected to be able to eat for at least 5 to 7 days or when inadequate intake persists for that period, initiation of tube feedings or TPN is indicated. No disease process benefits from starvation, and development or progression of nutritional deficits may contribute to complications such as pressure ulcers, pulmonary or urinary tract infections, and sepsis, which prolong hospitalization, increase the costs of care, and may even result in death.

Blood glucose control is especially important in the care of surgical patients. Hyperglycemia in the early postoperative period is associated with increased rates of hospital-acquired infection. To maintain tight control of blood glucose, glucose levels are monitored regularly, usually several times a day until the patient is stable. Regular insulin added to the solution is the most common method of managing hyperglycemia in the patient receiving TPN. Multiple injections of regular insulin may be used to maintain tight control of blood glucose in the enterally fed patient.

In patients receiving enteral tube feedings, the postpyloric route (via nasoduodenal, nasojejunal, or jejunostomy tube) may be the most effective, because gastroparesis may limit tolerance of intragastric tube feedings.34 Postpyloric feedings are given continuously because dumping syndrome and poor absorption may occur if feedings are given rapidly into the small bowel. Continuous enteral infusions are associated with improved control of blood glucose. Fiber-enriched formulas may slow the absorption of the carbohydrate, producing a more delayed and sustained glycemic response. Most standard formulas contain balanced proportions of carbohydrate, protein, and fats appropriate for diabetic patients. Specialized diabetic formulas have not shown improved outcomes compared to standard formulas.35

Severe Vomiting or Diarrhea in the Patient with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus.

When insulin-dependent patients experience vomiting and diarrhea severe enough to interfere significantly with oral intake or result in excessive fluid and electrolyte losses, adequate carbohydrates and fluids must be supplied. Nausea and vomiting should be treated with antiemetic medication.34 Delayed gastric emptying is common in diabetes and may improve with administration of prokinetic agents.34 Small amounts of food or liquids taken every 15 to 20 minutes are generally the best tolerated by the patient with nausea and vomiting. Foods and beverages containing approximately 15 g of carbohydrate include  cup regular gelatin,

cup regular gelatin,  cup custard,

cup custard,  cup regular ginger ale,

cup regular ginger ale,  cup regular soft drink, and

cup regular soft drink, and  cup orange or apple juice. Blood glucose levels should be monitored at least every 2 to 4 hours.

cup orange or apple juice. Blood glucose levels should be monitored at least every 2 to 4 hours.

Administering Nutrition Support

Enteral Nutrition

Whenever possible, the enteral route is the preferred method of feeding. Patients with abdominal trauma in particular have lower morbidity and mortality rates if fed enterally rather than parenterally.

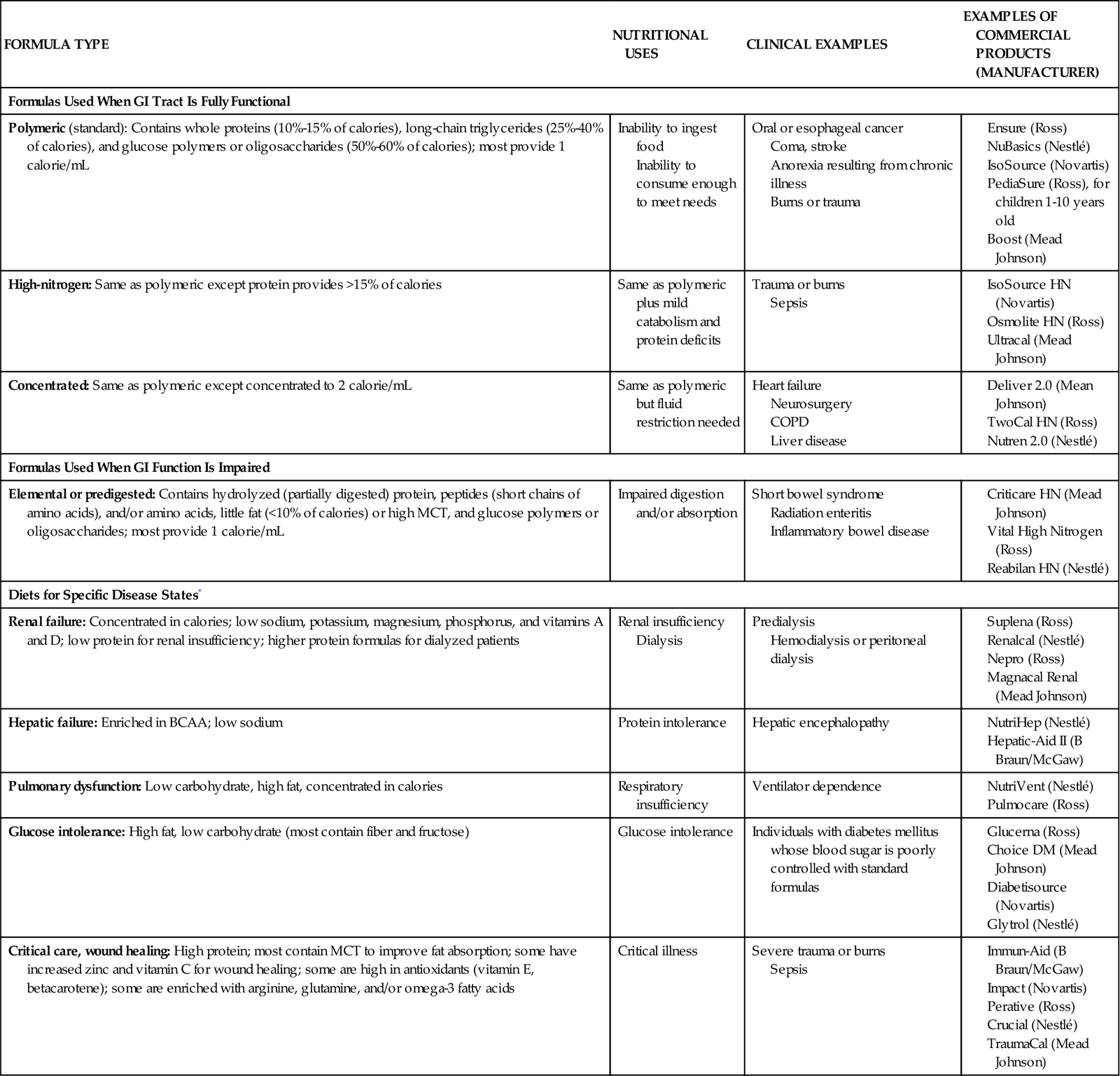

There are a variety of commercial enteral feeding products, some of which are designed to meet the specialized needs of the critically ill. Products designed for the stressed patient with trauma or sepsis are usually rich in glutamine, arginine, and antioxidant nutrients (e.g., vitamins C, E, and A; selenium). The antioxidants help to reduce oxidative injury to the tissues (e.g., from reperfusion injury). Some products can be consumed orally, but it can be difficult for the critically ill patient to consume enough orally to meet the increased needs associated with stress. Refer to Table 6-3 for enteral formulas.

TABLE 6-3

| FORMULA TYPE | NUTRITIONAL USES | CLINICAL EXAMPLES | EXAMPLES OF COMMERCIAL PRODUCTS (MANUFACTURER) |

| Formulas Used When GI Tract Is Fully Functional | |||

| Polymeric (standard): Contains whole proteins (10%-15% of calories), long-chain triglycerides (25%-40% of calories), and glucose polymers or oligosaccharides (50%-60% of calories); most provide 1 calorie/mL | Inability to ingest food Inability to consume enough to meet needs |

Oral or esophageal cancer Coma, stroke Anorexia resulting from chronic illness Burns or trauma |

|

| High-nitrogen: Same as polymeric except protein provides >15% of calories | Same as polymeric plus mild catabolism and protein deficits | Trauma or burns Sepsis |

|

| Concentrated: Same as polymeric except concentrated to 2 calorie/mL | Same as polymeric but fluid restriction needed | Heart failure Neurosurgery COPD Liver disease |

|

| Formulas Used When GI Function Is Impaired | |||

| Elemental or predigested: Contains hydrolyzed (partially digested) protein, peptides (short chains of amino acids), and/or amino acids, little fat (<10% of calories) or high MCT, and glucose polymers or oligosaccharides; most provide 1 calorie/mL | Impaired digestion and/or absorption | Short bowel syndrome Radiation enteritis Inflammatory bowel disease |

|

| Diets for Specific Disease States* | |||

| Renal failure: Concentrated in calories; low sodium, potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, and vitamins A and D; low protein for renal insufficiency; higher protein formulas for dialyzed patients | Renal insufficiency Dialysis |

Predialysis Hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis |

|

| Hepatic failure: Enriched in BCAA; low sodium | Protein intolerance | Hepatic encephalopathy | |

| Pulmonary dysfunction: Low carbohydrate, high fat, concentrated in calories | Respiratory insufficiency | Ventilator dependence | |

| Glucose intolerance: High fat, low carbohydrate (most contain fiber and fructose) | Glucose intolerance | Individuals with diabetes mellitus whose blood sugar is poorly controlled with standard formulas | |

| Critical care, wound healing: High protein; most contain MCT to improve fat absorption; some have increased zinc and vitamin C for wound healing; some are high in antioxidants (vitamin E, betacarotene); some are enriched with arginine, glutamine, and/or omega-3 fatty acids | Critical illness | Severe trauma or burns Sepsis |

|

*These diets may be beneficial for selected patients; costs and benefits must be considered. (From Urden LD, Stacy KM, Lough ME: Critical care nursing: Diagnosis and management, ed 6, St. Louis, 2010, Mosby.)

Oral Supplementation

Oral supplementation may be necessary for patients who can eat and have normal digestion and absorption but simply cannot consume enough regular foods to meet caloric and protein needs. Patients with mild to moderate anorexia, burns, or trauma may be included in this category.

Tube Feeding

Tube feedings are used for patients who have at least some digestive and absorptive capability but are unwilling or unable to consume enough by mouth. Patients with profound anorexia and those experiencing severe stress (e.g., major burns, trauma) that greatly increases their nutritional needs often benefit from tube feedings. Individuals who require elemental formulas because of impaired digestion or absorption or specialized formulas for altered metabolic conditions such as renal or hepatic failure usually require tube feeding because the unpleasant flavors of the free amino acids, peptides, or protein hydrolysates used in these formulas are very difficult to mask.

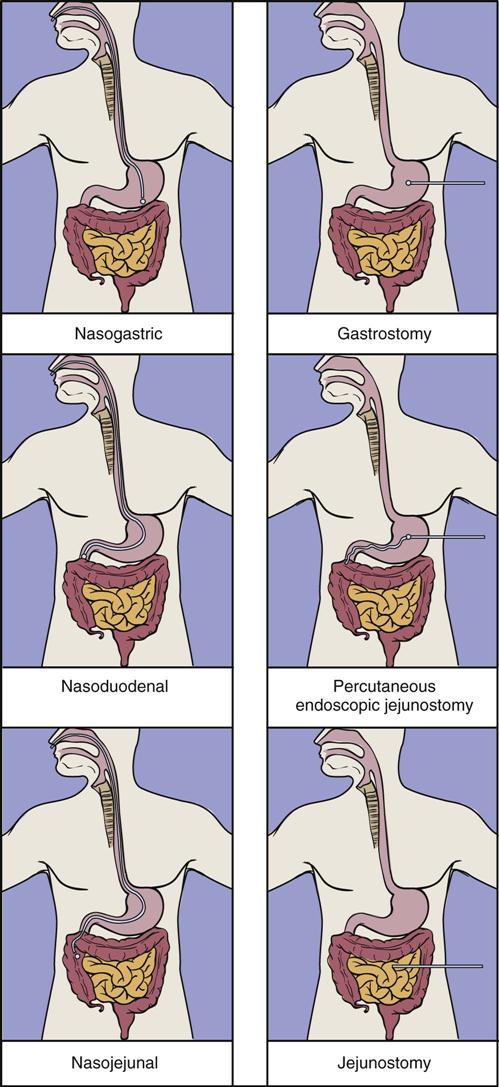

Location and Type of Feeding Tube

Nasal intubation is the simplest and most common route for gaining access to the GI tract; this method allows access to the stomach, duodenum, or jejunum. Tube enterostomy—a gastrostomy or jejunostomy—is used primarily for long-term feedings (6 to 12 weeks or more) and when obstruction makes the nasoenteral route inaccessible. Tube enterostomies may also be used for the patient who is at risk for tube dislodgment because of severe agitation or confusion. A conventional gastrostomy or jejunostomy is often performed at the time of other abdominal surgery. The percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube has become extremely popular because it can be inserted without the use of general anesthetics. Percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (PEJ) tubes are also used.

Transpyloric feedings via nasoduodenal, nasojejunal, or jejunostomy tubes are typically used when there is a risk of pulmonary aspiration, because theoretically the pyloric sphincter provides a barrier that lessens the risk of regurgitation and aspiration. If nasogastric tubes are used, choosing the smallest possible tube diameter reduces the risk of gastroesophageal reflux and pulmonary aspiration. Transpyloric feedings have an advantage over intragastric feedings for patients with delayed gastric emptying, such as those with head injury, gastroparesis associated with uremia or diabetes, or postoperative ileus. Small bowel motility returns more quickly than gastric motility after surgery, and thus it is often possible to deliver transpyloric feedings within a few hours of injury or surgery.36 Promotility agents such as metoclopramide may improve feeding tolerance.37 See Figure 6-2 for location of tube feeding sites.

Nursing Management

The nurse’s role in delivery of tube feedings usually includes (1) insertion of the tube, if a temporary tube is used; (2) maintenance of the tube; (3) administration of the feedings; (4) prevention and detection of complications associated with this form of therapy; and (5) participation in assessment of the patient’s response to tube feedings.

Tube Placement.

Critical care nurses are usually familiar with tube insertion, and therefore this topic is not discussed here. However, it is well to remember that if transpyloric positioning is desirable, administration of metoclopramide or erythromycin before tube insertion increases the likelihood of tube passage through the pylorus.38

Correct tube placement must be confirmed before initiation of feedings and regularly throughout the course of enteral feedings. Radiographs are the most accurate way of assessing tube placement, but repeated radiographs are costly and can expose the patient to excessive radiation. An inexpensive and relatively accurate alternative method involves assessing the pH of fluid removed from the feeding tube; some tubes are equipped with pH monitoring systems.

If the pH is less than 4.0 in patients not receiving gastric acid inhibitors, or less than 5.5 in patients who are receiving acid inhibitors, the tube tip is likely to be in the stomach.39 Intestinal secretions usually have a pH greater than 6.0, and respiratory tract fluids usually have a pH greater than 5.5. The esophagus may have an acid pH, which may cause confusion between esophageal and gastric placement. However, other clues can help in identifying a tube that has its distal tip in the esophagus: it may be especially difficult to aspirate fluid out of the tube; a large portion of the tube may extend out of the body (although a tube inserted to the proper length could be coiled in the esophagus); and belching often occurs immediately after air is injected into the tube.39

Assessing both the pH and the bilirubin concentration of fluid aspirated from the feeding tube is a promising new method for confirming tube placement.40 The bilirubin concentration in tracheobronchial and pleural fluid and in the stomach is approximately 90% less than in the intestine. Therefore the nurse who obtains fluid with a pH greater than 5.0 and a low bilirubin concentration from a feeding tube can be relatively sure that the distal tip of the tube is in the pulmonary system.40 Measurement of end-tidal CO2 also shows promise for confirming tube placement in ventilated patients.

Formula Delivery.

Careful attention to administration of tube feedings can prevent many complications. Very clean or aseptic technique in the handling and administration of the formula can help prevent bacterial contamination and a resultant infection. The optimal schedule for delivery of feedings also is important. Tube feedings may be administered intermittently or continuously.

Bolus feedings, which are intermittent feedings delivered rapidly into the stomach or small bowel, are likely to cause distention, vomiting, and dumping syndrome with diarrhea. Instead of using bolus feedings, nurses can gradually drip intermittent feedings, with each feeding lasting 20 to 30 minutes or longer, to promote optimal assimilation. The question of which feeding schedule—continuous or intermittent—is superior in critically ill patients remains unanswered.

Prevent or Correct Complications.

Some of the more common complications of tube feeding are pulmonary aspiration, diarrhea, constipation, tube occlusion, and gastric retention (Table 6-4).

TABLE 6-4

MANAGEMENT OF TUBE FEEDING COMPLICATIONS

| COMPLICATION | POSSIBLE CAUSE | SUGGESTED INTERVENTION |

| Pulmonary aspiration* | Feeding tube in esophagus or respiratory tract | Confirm proper placement of tube before administering any feeding; check placement at least every 4-8 hrs during continuous feedings. |

| Regurgitation of formula | Consider giving feeding into small bowel rather than stomach; keep head elevated 30-45 degrees during feedings; stop feedings temporarily during treatments such as chest physiotherapy. | |

| Diarrhea | Antibiotic therapy | Antidiarrheal medications may be ordered if the possibility of infection with Clostridium difficile has been ruled out; Lactobacillus or Saccharomyces boulardii are sometimes given enterally in an effort to establish benign gut flora. |

| Hypertonic medications (e.g., KCl or medications containing sorbitol) | Dilute enteral medications well; evaluate sorbitol content of medications. | |

| Malnutrition/hypoalbuminemia | Use continuous rather than bolus feedings; consider a formula with MCT and/or soluble fiber. | |

| Bacterial contamination | Use scrupulously clean formula preparation and administration techniques; refrigerate home-prepared, reconstituted, or opened cans of formula until ready to use, and use all such products within 24 hrs. | |

| Predisposing illness (e.g., short bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, AIDS) | Use continuous feedings; consider a formula with MCT and/or soluble fiber. | |

| Lactose intolerance | Use a lactose-free formula. | |

| Fecal impaction | Perform digital examination to rule out fecal impaction with seepage of liquid stool around the obstruction. | |

| Intestinal mucosal atrophy | Consider use of formula containing soluble fiber and MCT. | |

| Constipation | Lack of fiber | Consider fiber-containing formula; ensure that fluid intake is adequate; stool softeners may be ordered. |

| Tube occlusion | Administration of medications via tube | Avoid crushing tablets; administer medications in elixir or suspension form whenever possible; irrigate feeding tube with water before and after giving medications; never mix medication with enteral formulas because this may cause clumping of formula. |

| Sedimentation of formula | Irrigate tube with water <†> every 4-8 hrs during continuous feedings and after every intermittent feeding; irrigate tubes well if gastric residuals are measured, as gastric juices left in the tube may cause precipitation of formula in the tube; instilling pancreatic enzyme into the tube may clear some occlusions. | |

| Delayed gastric emptying | Serious illness, diabetic gastroparesis, prematurity, surgery, high-fat content of formula, hyperglycemia | Consult with physician regarding whether feedings can be administered into the small bowel, a lower-fat formula can be used, or metoclopramide can be administered to stimulate gastric emptying; improve glycemic control if hyperglycemia exists. |

| Hyperglycemia | Excessive glucose in feedings/fluids, glucose intolerance due to stress/sepsis, concomitant disease (e.g., diabetes), drug therapy (e.g., corticosteroids) | Monitor serum glucose several times daily until stable and regularly thereafter; correct underlying illness if possible; reduce enteral or parenteral feedings if excessive; consider use of insulin; consider higher fat/lower carbohydrate formula. |

MCT, medium-chain triglyceride.

*Signs and symptoms of pulmonary aspiration include tachypnea, shortness of breath, hypoxia, and infiltrate on chest radiographs.

<†>Fluids such as cranberry juice or Coca-Cola are sometimes used as irrigants, in the belief that they are better than water at preventing tube occlusion. However, research has shown cranberry juice to be inferior to and Coca-Cola no better than water.

From Moore MC: Pocket Guide to Nutritional Assessment and Care, ed 5, St Louis, 2005, Mosby.

Total Parenteral Nutrition

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) refers to the delivery of all nutrients by the intravenous (IV) route. TPN is used when the GI tract is not functional or when nutritional needs cannot be met solely via the GI tract. Likely candidates for TPN include patients who have a severely impaired absorption (as in short bowel syndrome, collagen-vascular diseases, and radiation enteritis), intestinal obstruction, peritonitis, and prolonged ileus. In addition, some postoperative, trauma, and burn patients may need TPN to supplement the nutrient intake they are able to tolerate via the enteral route.

Types of Parenteral Nutrition

TPN involves administration of highly concentrated dextrose that ranges from 25% to 70%, providing a rich source of calories. Such highly concentrated dextrose solutions are hyperosmolar, as much as 1800 mOsm/L, and therefore must be delivered through a central vein.41 Peripheral parenteral nutrition (PPN) has a glucose concentration of 5% to 10% and may be delivered safely through a peripheral vein. PPN solution delivers nutrition support in a large volume that cannot be tolerated by patients who require fluid restriction. It provides short-term nutrition support for a few days to less than 2 weeks.

Regardless of the route of administration, both PPN and TPN provide glucose, fat, protein, electrolytes, vitamins, and trace elements. Although dextro-amino acid solutions are commonly thought of as good growth media for microorganisms, they actually suppress the growth of most organisms usually associated with catheter-related sepsis, except yeasts. However, because the many manipulations required to prepare solutions increase the possibility of contamination, TPN solutions are best used with caution. They should be prepared under laminar flow conditions in the pharmacy, with avoidance of additions on the nursing unit. Solution containers need to be inspected for cracks or leaks before hanging, and solutions must be discarded within 24 hours of hanging. An in-line 0.22-micron filter, which eliminates all microorganisms but not endotoxins, may be used in administration of solutions. Use of the filter, however, cannot be substituted for good aseptic technique.

Nursing Management of Potential Complications

Nursing management of the patient receiving TPN includes catheter care, administration of solutions, prevention or correction of complications, and evaluation of patient responses to IV feedings. Refer to Table 6-5 for nursing management of TPN complications.

TABLE 6-5

NURSING MANAGEMENT OF TPN COMPLICATIONS

| COMPLICATION | SIGNS/SYMPTOMS | PREVENTION/INTERVENTION |

| Catheter site infection | Erythema, warmth, inflammation, and pus at the catheter insertion site | Insert catheter with maximal barrier precautions (gown, mask, gloves, drapes) and strict aseptic technique; use aseptic technique in maintaining the insertion site; monitor insertion site regularly; culture site and administer antibiotics as appropriate if infection is apparent. |

| Catheter-related sepsis | Fever, chills, glucose intolerance, positive blood culture; bacterial colony counts in blood from the catheter 5-10 times higher than in blood obtained from a peripheral site | Insert catheter with maximal barrier precautions (gown, mask, gloves, drapes) and strict aseptic technique; maintain an intact dressing; change if contaminated by vomitus, sputum, etc.; use aseptic technique whenever handling catheter, IV tubing, and TPN solutions; hang a single bottle of TPN no longer than 24 hrs and lipid emulsion no longer than 12 hrs; use a 0.22 µm filter with solutions that contain lipids; avoid using single-lumen nontunneled catheter for blood sampling and infusion of non-TPN solutions if possible. |

| Air embolism | Dyspnea, cyanosis, tachycardia hypotension, possibly death | Use Luer lock system or secure all connections well; Groshong catheter, which has valve at tip, may reduce risk of air embolism; use an in-line 0.22 µm air-eliminating filter if solutions do not contain lipids or 1.2 µm or larger if solutions contain lipids; have patient perform Valsalva’s maneuver during tubing changes; if air embolism is suggested, place patient in left lateral decubitus position and administer oxygen; immediately notify physician, who may attempt to aspirate air from the heart. |

| Central venous thrombosis | Unilateral edema of neck, shoulder, and arm; development of collateral circulation on chest; pain in insertion site | Follow measures to prevent sepsis; repeated or traumatic catheterizations are most likely to result in thrombosis; treatment usually includes anticoagulation; if symptoms are not too severe, thrombolytic therapy may be attempted, but catheter removal is usually necessary. |

| Catheter occlusion or semiocclusion | No flow or sluggish flow through the catheter; or infusion through the catheter possible, but blood cannot be aspirated from the catheter | Flush catheter with heparinized saline if infusion is stopped temporarily; if catheter appears to be occluded, attempt to aspirate the clot; thrombolytic agent may restore patency if clotted or occluded by fibrin sheath; hydrochloric acid, 0.1 N, has been used to clear drug precipitates and 70% ethanol to clear lipid precipitates. |

| Hypoglycemia | Diaphoresis, shakiness, confusion, loss of consciousness | Do not discontinue TPN abruptly, taper rate over several hrs; use pump to regulate infusion so that it remains ±10% of ordered rate; if hypoglycemia is suggested, then administer oral carbohydrate; if oral intake is contraindicated or patient is unconscious, a bolus of IV dextrose may be used. |

| Hyperglycemia | Thirst, headache, lethargy, increased urination | Monitor blood glucose frequently until stable; TPN is usually initiated at a slow rate or with a low dextrose concentration and increased over 2-3 days to avoid hyperglycemia; the patient may require insulin added to the TPN if the problem is severe. |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | Serum triglyceride concentrations elevated (especially serious if >400 mg/dL); serum may appear turbid | Monitor serum triglycerides after each increase in rate and at least 3 times weekly until stable in patients receiving lipid emulsions; reduce lipid infusion rate or administer low-dose heparin with lipid emulsions if elevated levels are observed. |

From Moore MC: Pocket Guide to Nutritional Assessment and Care, ed 5, St Louis, 2005, Mosby.

Because TPN requires an indwelling catheter in a central vein, it carries an increased risk of sepsis as well as potential insertion-related complications such as pneumothorax and hemothorax. Air embolism is also more likely with central vein TPN. Patients requiring multiple IV therapies and frequent blood sampling usually have multilumen central venous catheters, and TPN is often infused via these catheters.

Some clinical studies have reported that catheter-related sepsis is higher with multilumen catheters; others have found no difference compared with single-lumen catheters.42 Clearly, patients requiring multilumen catheters are likely to be very ill and immunocompromised, and scrupulous aseptic technique is essential in maintaining multilumen catheters. The manipulation involved in frequent changes of IV fluid and obtaining blood specimens through these catheters increases the risk of catheter contamination. Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) allow central venous access through long catheters inserted in peripheral sites. This reduces the risk of complications associated with percutaneous cannulation of the subclavian vein and provides an alternative to PPN.43

The indwelling central venous catheter provides an excellent nidus for infection. Catheter-related infections arise from endogenous skin flora, contamination of the catheter hub, seeding of the catheter by organisms carried in the bloodstream from another site, or contamination of the infusate. Good hand hygiene and scrupulous aseptic technique in all aspects of catheter care and TPN delivery are the primary steps for prevention of catheter-related infections. Other measures to reduce the incidence of catheter-related infections include using maximal barrier precautions (i.e., cap, mask, sterile gloves, sterile drape) at the time of insertion, tunneling the catheter underneath the skin, use of a 2% chlorhexidine preparation for skin cleansing, no routine replacement of the central venous catheter for prevention of infection, and use of antiseptic/antibiotic-impregnated central venous catheters.44

Metabolic complications associated with parenteral nutrition include glucose intolerance and electrolyte imbalance. Slow advancement of the rate of TPN (25 ml/hr) to goal rate will allow pancreatic adjustment to the dextrose load. Capillary blood glucose should be monitored every 4 to 6 hours. Insulin can be added to the TPN solution or can be infused as a separate drip to control glucose levels. Rapid cessation of TPN may not lead to hypoglycemia; however, tapering the infusion over 2 to 4 hours is recommended.45

Serum electrolyte levels are obtained upon starting TPN. During critical illness, levels should be monitored and corrected daily, and then weekly or twice weekly once the patient is more stable. The refeeding syndrome is a potentially lethal condition characterized by generalized fluid and electrolyte imbalance. It occurs as a potential complication after initiation of oral, enteral, or parenteral nutrition in malnourished patients. During chronic starvation, several compensatory metabolic changes occur. The reintroduction of carbohydrates and amino acids leads to increased insulin production. This creates an anabolic environment that increases intracellular demand for phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, vitamins, and minerals.46 These metabolic demands result in severe shifts from the extracellular compartment. Increased insulin levels also result in fluid retention. Severe hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, and hypomagnesemia result in altered cardiac, gastrointestinal, and neurologic function. In particular, hypophosphatemia causes a decrease in 2,3-diphosphosoglycerate (2,3 DPG) and also limits the many reactions that require ATP. As a result, hypophosphatemia and other electrolyte deficiencies may lead to respiratory failure, congestive heart failure, and dysrhythmias.

It is important to anticipate refeeding syndrome in patients who may be at risk. Patients with chronic malnutrition or underfeeding, chronic alcoholism, or anorexia nervosa, or those maintained NPO for several days with evidence of stress are at risk for refeeding syndrome.47 In high-risk patients, nutrition support should be started cautiously at 25% to 50% of required calories and slowly advanced over 3 to 4 days as tolerated. Close monitoring of serum electrolyte levels before and during feeding is essential. Normal values do not always reflect total body stores. Correction of preexisting electrolyte imbalances is necessary before initiation of feeding. Continued monitoring and supplementation with electrolytes and vitamins is necessary throughout the first week of nutrition support.47

Lipid Emulsion

Lipids or intravenous fat emulsions (IVFE) provide calories for energy and prevent essential fatty acid depletion. In contrast to dextro-amino acid solutions, IVFE provide a rich environment for the growth of bacteria and fungi including Candida albicans. Furthermore, IVFE cannot be filtered through an in-line 0.22-µm filter, because some particles in the emulsions have larger diameters than this. Lipids may be infused into the TPN line downstream from the filter. No other drugs should be infused into a line containing lipids or TPN. Lipid emulsions are handled with strict asepsis, and they must be discarded within 12 to 24 hours of hanging. There is a trend toward mixing lipid emulsions with dextro-amino acid TPN solutions; these are called 3-in-1 solutions or total nutrient admixtures (TNA). Consolidating the nutrients in one container is more economical and saves nursing time, although TNA solutions may be less stable.41

Evaluating Response to Nutrition Support

A multidisciplinary approach is required in evaluating the effects of nutrition support on clinical outcomes. Assessment of response to nutrition support is an ongoing process that involves anthropometric measurements, physical examination, and biochemical evaluation. Daily monitoring of nutritional intake is an important aspect of critical care and is a key element in preventing problems associated with underfeeding and overfeeding. Daily weights and the maintenance of accurate intake-and-output records are crucial for evaluating nutritional progress and the state of hydration in the patient receiving nutrition support. A variety of metabolic complications (hypernatremia and hyponatremia, hyperkalemia and hypokalemia, hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia and hypophosphatemia, etc.) as well as deficiencies of vitamins and minerals occur in patients receiving enteral and parenteral nutrition. For this reason, adequacy of electrolytes, calcium, phosphate, magnesium, zinc, and other nutrients must be assessed regularly (frequently during the early stages, less frequently in stable long-term patients) for the duration of nutrition support. Serum levels of electrolytes, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium serve as a guide to the amount of these nutrients that has to be supplied; blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels reflect the adequacy of renal function to handle nutrition support; blood glucose is an indicator of the patient’s tolerance of the carbohydrate; prealbumin is an indicator of the adequacy of nutrition support; and serum triglyceride concentrations (in patients receiving intravenous lipid emulsions) reflect the ability of the tissues to metabolize the lipids.

Recently, the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) published The Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient. The publication is based on an extensive review of 307 articles and is intended for the care of critically ill adults who require a stay of greater than three days in the critical care area. All practitioners who care for this target population are encouraged to become familiar with these evidence-based guidelines.48

It is within the scope of practice for critical care nurses to calculate caloric requirements and analyze daily caloric delivery, advocate for early nutrition support, and minimize feeding interruptions through careful patient assessment and interruption analysis. In addition to monitoring changes in weight and laboratory values, the nurse is the health care team member who has the most constant contact with the patient and who is therefore uniquely qualified to evaluate feeding tolerance and adequacy of delivery.