Chapter 6 Nose and Mouth

A. The Nose

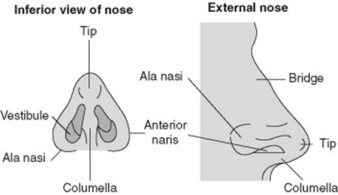

(2) The External Nose

8 What is lupus pernio?

It is a chronic, nonblanching, diffuse, and purple skin discoloration of the external nose, in the absence of true nasal enlargement (Fig. 6-2). Hence, it differs from rhinophyma. A sign of active sarcoid, it may occur with uveitis, erythema nodosum, and pulmonary involvement. It may also coexist with lesions of the ears, cheeks, hands, and fingers. The term lupus refers to any disfiguring skin condition that, like a wolf (lupus in Latin) “devours” the patient’s facial features. It is thus used with modifying terms to designate various disfiguring skin diseases, such as lupus verrucosus, lupus erythematosus, lupus tuberculosis, lupus vulgaris, and, of course, lupus pernio. Pernio is Latin for frostbite and refers to the peculiar violet-bluish hue of the condition (see Chapter 3, The Skin, question 265).

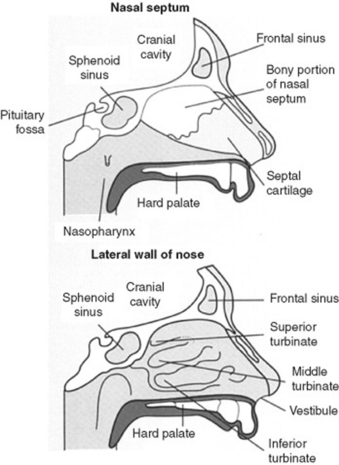

(3) The Internal Nose

10 What are the normal structures of the internal nose?

The normal internal structures are shown in Fig. 6-3:

1. The vestibules. As indicated by the term, these are paired internal widenings, immediately beyond each naris. They are delimited:

Medially by the septum. Like the external nose, this is partly bony and partly cartilaginous. The word septum is an anglicized adaptation of the Latin saepire, “to erect a hedgerow.” Indeed, the function of the septum is to provide a medial boundary to each vestibule.

Medially by the septum. Like the external nose, this is partly bony and partly cartilaginous. The word septum is an anglicized adaptation of the Latin saepire, “to erect a hedgerow.” Indeed, the function of the septum is to provide a medial boundary to each vestibule.2. Deeply beyond the vestibules are the turbinates, or conchae. These are curving bony structures that project into the internal nose. There are three turbinates (and three corresponding meatuses) in each nasal cavity: superior, middle, and inferior. Their main function is to increase the nasal surface for humidification, temperature control, and filtering of inhaled air. To do so, they are covered by a well-vascularized and erectile mucosa.

13 What is the significance of flaring of the nostrils?

Flaring of the nostrils (i.e., of the alae of the nose) is a sign of increased work of breathing, typical of impending respiratory failure. It is often associated with other findings of distress, such as respiratory alternans and abdominal paradox (see Chapter 13, Chest Inspection, Palpation, and Percussion, questions 52–58). It also can occur in peritonitis as a result of impaired and painful excursion of the diaphragm.

14 What are the best tools for inspecting nares and internal nose?

15 Is inspection of nasal secretions useful?

A clear discharge is suggestive of viral or atopic rhinitis.

A clear discharge is suggestive of viral or atopic rhinitis.

A yellow discharge may instead indicate an early suppurative process.

A yellow discharge may instead indicate an early suppurative process.

A green discharge is quite consistent with purulent sinusitis.

A green discharge is quite consistent with purulent sinusitis.

Obviously, a bloody discharge suggests anterior epistaxis.

Obviously, a bloody discharge suggests anterior epistaxis.

A dark and almost black discharge (especially in comatose diabetics) argues for mucormycosis.

A dark and almost black discharge (especially in comatose diabetics) argues for mucormycosis.

17 What are the causes of swelling/bumps in the nasal septum?

All require ENT referral, since an untreated hematoma (or abscess) may result in septal perforation.

23 What are the common causes of a septal perforation?

Traumatic: Facial injury or self-induced lesions (nose picking/piercing)

Traumatic: Facial injury or self-induced lesions (nose picking/piercing)

Iatrogenic: Prior septal surgery, nasogastric tube placement, or nasal intubation

Iatrogenic: Prior septal surgery, nasogastric tube placement, or nasal intubation

Inflammatory/malignant: Often the sequela of untreated septal hematomas or abscesses

Inflammatory/malignant: Often the sequela of untreated septal hematomas or abscesses

Cocaine snorting: One of the most frequent causes today, often presenting with large and expanding perforations. Cocaine contains adulterants that may irritate the mucosa, plus has strong alpha-agonist effects (causing vasoconstriction and ischemia of the nasal cartilage). Nasal obstruction often accompanies perforation.

Cocaine snorting: One of the most frequent causes today, often presenting with large and expanding perforations. Cocaine contains adulterants that may irritate the mucosa, plus has strong alpha-agonist effects (causing vasoconstriction and ischemia of the nasal cartilage). Nasal obstruction often accompanies perforation.

24 What are the less-common causes of perforation?

Chemical irritants (chromic or sulfuric acid fumes, glass dust, mercurials, and phosphorous)

Chemical irritants (chromic or sulfuric acid fumes, glass dust, mercurials, and phosphorous)

Infections (tuberculosis, syphilis, and, more rarely, leprosy)

Infections (tuberculosis, syphilis, and, more rarely, leprosy)

Collagen vascular diseases (Wegener’s, midline granuloma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, and progressive system sclerosis)

Collagen vascular diseases (Wegener’s, midline granuloma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, and progressive system sclerosis)

28 What results in swelling of the nasal mucosa?

Viral: Nasal and oropharyngeal infections by either rhinoviruses or adenoviruses

Viral: Nasal and oropharyngeal infections by either rhinoviruses or adenoviruses

Atopic: Pollen or dander exposure causing nasal congestion, allergic (serous) conjunctivitis, and sneezing

Atopic: Pollen or dander exposure causing nasal congestion, allergic (serous) conjunctivitis, and sneezing

Vasomotor: Response to a specific inhalant, characterized by boggy edema of the mucosa and marked tearing. Inhalants may either be noxious to all (such as tear gas) or only to some. For example, perfumes may elicit an idiosyncratic response in a few predisposed individuals, causing pronounced swelling of the nasal mucosa.

Vasomotor: Response to a specific inhalant, characterized by boggy edema of the mucosa and marked tearing. Inhalants may either be noxious to all (such as tear gas) or only to some. For example, perfumes may elicit an idiosyncratic response in a few predisposed individuals, causing pronounced swelling of the nasal mucosa.

33 What is anosmia?

It is the congenital or acquired absence of smell (from the Greek an, lack of, and osme, smell).

Acquired anosmia may result from a long list of disease processes, affecting either the central nervous system or nose. Among them are multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, liver cirrhosis, chronic renal insufficiency, Cushing’s syndrome, cystic fibrosis, sarcoidosis, allergic rhinitis, nasal polyposis, and zinc deficiency. Still, sequelae of a viral infection are often the most common reasons for acquired reversible anosmia.

Acquired anosmia may result from a long list of disease processes, affecting either the central nervous system or nose. Among them are multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, liver cirrhosis, chronic renal insufficiency, Cushing’s syndrome, cystic fibrosis, sarcoidosis, allergic rhinitis, nasal polyposis, and zinc deficiency. Still, sequelae of a viral infection are often the most common reasons for acquired reversible anosmia.

Congenital anosmia is almost always caused by Kallmann’s syndrome. Described by the German psychiatrist Franz J. Kallmann (1897–1965), this consists of familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with or without anosmia (usually characterized by congenital absence of olfactory lobes). Kallmann’s is inherited through sex-linked recessive or autosomal transmission, with expression mostly in males. It can be treated with gonadotropins.

Congenital anosmia is almost always caused by Kallmann’s syndrome. Described by the German psychiatrist Franz J. Kallmann (1897–1965), this consists of familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with or without anosmia (usually characterized by congenital absence of olfactory lobes). Kallmann’s is inherited through sex-linked recessive or autosomal transmission, with expression mostly in males. It can be treated with gonadotropins.

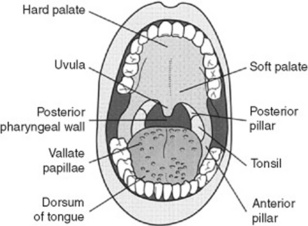

B. The Oral Cavity

(2) Posterior Pharynx and Tonsils

37 What is a cleft palate?

A congenital deformity that is usually corrected in infancy but may persist into adulthood. It is quite common (1 case in 1000 live births, with or without cleft lip), with greater prevalence in Native Americans (3.6 cases per 1000 live births), and lower in African Americans (0.3 cases per 1000 live births). Of all cases, 20% are an isolated cleft lip; 50% are a cleft lip and palate, and 30% are a cleft palate alone. Cleft lip and palate together are more common in males, whereas isolated cleft palate is more common in females. Bifid uvula occurs in 1 of 80 patients, often in isolation (see question 38).

38 What is the uvula? What disease processes may affect it?

Absent uvula: Usually due to surgical removal as part of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) for obstructive sleep apnea. May result in inhalation of swallowed fluids.

Absent uvula: Usually due to surgical removal as part of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) for obstructive sleep apnea. May result in inhalation of swallowed fluids.

Bifid uvula: Fascinating but entirely benign normal variant, wherein the uvula is congenitally forked. Not a sign of lying, it may instead be associated with an occult cleft palate. Look for it.

Bifid uvula: Fascinating but entirely benign normal variant, wherein the uvula is congenitally forked. Not a sign of lying, it may instead be associated with an occult cleft palate. Look for it.

Bobbing uvula: Patients with chronic and severe aortic insufficiency may have a rhythmic pulsatile movement of the uvula (Mueller’s sign). This is the equivalent of the de Musset sign (see Chapter 1, Facies, General Appearance, and Body Habitus, questions 51 and 54) and is quite rare nowadays, thanks to timely valvular treatment.

Bobbing uvula: Patients with chronic and severe aortic insufficiency may have a rhythmic pulsatile movement of the uvula (Mueller’s sign). This is the equivalent of the de Musset sign (see Chapter 1, Facies, General Appearance, and Body Habitus, questions 51 and 54) and is quite rare nowadays, thanks to timely valvular treatment.

Neoplastic uvula (squamous cell degeneration): As for many other oropharyngeal structures.

Neoplastic uvula (squamous cell degeneration): As for many other oropharyngeal structures.

43 What are the causes of an exudate (i.e., pus) on the posterior pharynx?

Many agents can cause exudative pharyngitis (Table 6-1), the most important being upper respiratory tract viruses, group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, and the EBV.

| Pathogen | Probability (%) |

|---|---|

| Viral | 50–80 |

| Streptococcal | 5–36 |

| Epstein-Barr virus | 1–10 |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | 2–5 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 2–5 |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | 1–2 |

| Haemophilus influenzae type b | 1–2 |

| Candidiasis | <1 |

| Diphtheria | <1 |

(Data from Ebell M, et al: Does this patient have strep throat? JAMA 284:2912–2918, 2000.)

44 What are the clinical features of viral upper respiratory tract infections?

Pharyngeal vesicles and ulcers. These are so typical as to argue against group A streptococci being the cause of the patient’s sore throat (see herpangina, questions 87 and 89).

48 What is infectious mononucleosis? What are its features?

Severe exudative pharyngitis with tonsillar swelling, sore throat, and often dysphagia. The involved mucosa is swollen, erythematous, coated with a grayish exudate, and typically characterized by small erosions and petechiae. Other features include splenomegaly and hepatomegaly.

Severe exudative pharyngitis with tonsillar swelling, sore throat, and often dysphagia. The involved mucosa is swollen, erythematous, coated with a grayish exudate, and typically characterized by small erosions and petechiae. Other features include splenomegaly and hepatomegaly.

Prominent cervical lymphadenopathy. This occurs in >90% of young patients, typically presenting as enlarged, symmetric, and tender anterior nodes—which are usually involved in only a few other conditions. Note, however, that posterior nodes also may be involved (in 60% of the cases), and that adenopathy is absent in more than 70% of patients older than 40%).

Prominent cervical lymphadenopathy. This occurs in >90% of young patients, typically presenting as enlarged, symmetric, and tender anterior nodes—which are usually involved in only a few other conditions. Note, however, that posterior nodes also may be involved (in 60% of the cases), and that adenopathy is absent in more than 70% of patients older than 40%).

Severe constitutional symptoms, such as fatigue, arthralgias, myalgias, lethargy, functional impairment, and nausea. Hemolytic anemia also may occur. In most patients, acute signs and symptoms resolve within 3–4 weeks, but lethargy can persist much longer—even months.

Severe constitutional symptoms, such as fatigue, arthralgias, myalgias, lethargy, functional impairment, and nausea. Hemolytic anemia also may occur. In most patients, acute signs and symptoms resolve within 3–4 weeks, but lethargy can persist much longer—even months.

49 What are the glandular fever–like syndromes?

HIV (at time of seroconversion): Since this is an early stage, the patient is viremic (and thus highly infectious), but HIV-antibody negative.

HIV (at time of seroconversion): Since this is an early stage, the patient is viremic (and thus highly infectious), but HIV-antibody negative.

CMV: Compared with infectious mononucleosis (EBV), the lymphadenopathy of CMV is less prominent and the pharyngitis less severe.

CMV: Compared with infectious mononucleosis (EBV), the lymphadenopathy of CMV is less prominent and the pharyngitis less severe.

Toxoplasmosis: This is acquired through ingestion of either tissue cysts in raw or inadequately cooked meat (such as sheep and pig) or sporocysts on unwashed fruit or vegetables contaminated with cat feces. Cats are the definitive hosts of the parasite (Toxoplasma gondii), excreting it as cysts in their feces. Cysts can remain viable in soil for months, eventually infecting humans and animals (e.g., pigs and sheep). Infection is usually asymptomatic, although it can present with a glandular fever-like syndrome.

Toxoplasmosis: This is acquired through ingestion of either tissue cysts in raw or inadequately cooked meat (such as sheep and pig) or sporocysts on unwashed fruit or vegetables contaminated with cat feces. Cats are the definitive hosts of the parasite (Toxoplasma gondii), excreting it as cysts in their feces. Cysts can remain viable in soil for months, eventually infecting humans and animals (e.g., pigs and sheep). Infection is usually asymptomatic, although it can present with a glandular fever-like syndrome.

50 Can strep throat be diagnosed by history and physical examination?

No finding, if absent, can rule out the disease. The ones with lowest negative LR are:

51 What are the causes of a nodule in the posterior pharynx?

Human papilloma virus (HPV): This causes a warty lesion on the tonsils, tonsillar pillars, or even buccal mucosa. May degenerate into squamous cell carcinoma.

Human papilloma virus (HPV): This causes a warty lesion on the tonsils, tonsillar pillars, or even buccal mucosa. May degenerate into squamous cell carcinoma.

Squamous cell carcinoma: Presents as a papule or nodule in the posterior pharynx of 50- to 70-year-old patients, usually males (three to four times), often in association with smoking, tobacco-chewing, heavy ethanol ingestion, and HPV infection. About 90% of tonsillar cancers are squamous cell, 60% presenting with cervical metastases (bilateral in 15% of the cases), and 7% with distant spread. Note that carcinomas of the tonsils are not necessarily exophytic or ulcerated. In fact, they often look identical to lymphomas, distinguishable only by biopsy.

Squamous cell carcinoma: Presents as a papule or nodule in the posterior pharynx of 50- to 70-year-old patients, usually males (three to four times), often in association with smoking, tobacco-chewing, heavy ethanol ingestion, and HPV infection. About 90% of tonsillar cancers are squamous cell, 60% presenting with cervical metastases (bilateral in 15% of the cases), and 7% with distant spread. Note that carcinomas of the tonsils are not necessarily exophytic or ulcerated. In fact, they often look identical to lymphomas, distinguishable only by biopsy.

Lymphoma: The second most common type of tonsillar cancer, presenting as a submucosal mass in an otherwise asymmetric tonsillar enlargement. Ipsilateral adenopathy is common.

Lymphoma: The second most common type of tonsillar cancer, presenting as a submucosal mass in an otherwise asymmetric tonsillar enlargement. Ipsilateral adenopathy is common.

Peritonsillar abscess (quinsy): A tender nodule that follows exudative pharyngitis and is associated with erythema and uvular displacement. The term quinsy goes back to middle English (from the original Greek kunankhê, dog collar), but also brings to mind the fictional television character Dr. Quincy (Jack Klugman), the medical examiner whom a patient inevitably ended up seeing if (s)he did not receive prompt surgical drainage of a quinsy.

Peritonsillar abscess (quinsy): A tender nodule that follows exudative pharyngitis and is associated with erythema and uvular displacement. The term quinsy goes back to middle English (from the original Greek kunankhê, dog collar), but also brings to mind the fictional television character Dr. Quincy (Jack Klugman), the medical examiner whom a patient inevitably ended up seeing if (s)he did not receive prompt surgical drainage of a quinsy.

(3) Oral Mucosa

53 What is the magic of “Ahhhh”?

Saying “Ahhhh” is effective for two reasons:

It elevates the soft palate, thus allowing visualization of the base of the tongue, uvula, tonsillar pillars, and even hypopharynx.

It elevates the soft palate, thus allowing visualization of the base of the tongue, uvula, tonsillar pillars, and even hypopharynx.

It permits adequate assessment of the motor division of cranial nerves IX (glossopharyngeal) and X (vagus). In cases of bilateral damage to these nerves, saying “Ahhhh” will not elevate the uvula. In cases of unilateral damage, saying “Ahhhh” will instead deviate the uvula toward the intact side (it also will prevent the rising of the soft palate from the paralyzed side).

It permits adequate assessment of the motor division of cranial nerves IX (glossopharyngeal) and X (vagus). In cases of bilateral damage to these nerves, saying “Ahhhh” will not elevate the uvula. In cases of unilateral damage, saying “Ahhhh” will instead deviate the uvula toward the intact side (it also will prevent the rising of the soft palate from the paralyzed side).

55 What is the descriptive nomenclature of lesions in the oral mucosa?

One akin to that of dermatology (see Chapter 3, question 2), similarly relying on lesions’ size and characteristics to classify them as:

Other terms, such as vesicles and bullae for fluid-filled lesions, are similarly used.

56 What are the colors of oral lesions?

It depends on the lesion. Colors range from flesh to white, black, and red (Table 6-2).

| Flesh-Colored Lesions | Smoker’s melanosis |

| Wharton’s Duct | Hemochromatosis |

| Stensen’s Duct | Addison’s disease |

| Ranula | Melanoplakia |

| Torus (mandibularis, palatinus) | Malignant melanoma |

| Buccal exostosis | Red Lesions |

| White Lesions | Pyogenic granuloma |

| Thickening of oral mucosa (linea alba) | Erythema migrans |

| Hairy leukoplakia | Palatal petechiae |

| Oral thrush | Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Koplik spots | Ulcerated Lesions |

| Fordyce spots | Thermal injuries (burns) |

| Wickham sign | Aphthous ulcers (canker sore) |

| Squamous cells carcinoma | Automimmune gingivostomatitis |

| Pigmented Lesions | Viral gingivostomatitis |

| Amalgam tattoo | Primary syphilis (chancre) |

| Peutz-Jeghers syndrome | Squamous cells carcinoma |

57 What causes flesh-covered palpable lesions in the oral mucosa?

Wharton’s ducts are two tiny papules on the floor of the mouth (just under the tongue and 5 mm lateral to the frenulum, representing the opening of the submaxillary glands).

Wharton’s ducts are two tiny papules on the floor of the mouth (just under the tongue and 5 mm lateral to the frenulum, representing the opening of the submaxillary glands).

Stensen’s ducts represent instead the opening of the parotid glands. They are located on both sides of the buccal mucosa, directly opposite to the second upper molar and near the bite line.

Stensen’s ducts represent instead the opening of the parotid glands. They are located on both sides of the buccal mucosa, directly opposite to the second upper molar and near the bite line.

60 Who were Wharton and Stensen?

Thomas Wharton was one of the personal physicians to Oliver Cromwell and an active presence during the 1665 great plague of London.

Thomas Wharton was one of the personal physicians to Oliver Cromwell and an active presence during the 1665 great plague of London.

Niels Stensen was instead a Danish anatomist and geologist who lived first in Copenhagen, then in Leiden and Montpellier, and finally in Paris, where he investigated heart, brain, muscles, and glands. Stensen described the tetralogy of Fallot more than two centuries before Fallot himself and in 1661 discovered the homonymous excretory duct of the parotid gland. His anatomic studies eventually brought him to Florence, as court physician to Grand Duke Ferdinand II. There he was converted to Catholicism by a nun and became a priest. In his new devotion (and much to the dismay of his scientific colleagues), he completely abandoned science and spent the rest of his life ministering to Roman Catholics in northern Germany. His homonymous ducts are often called Steno’s ducts, from the Latinized version of Stensen into Nicolaus Stenonis, or, more simply, Steno.

Niels Stensen was instead a Danish anatomist and geologist who lived first in Copenhagen, then in Leiden and Montpellier, and finally in Paris, where he investigated heart, brain, muscles, and glands. Stensen described the tetralogy of Fallot more than two centuries before Fallot himself and in 1661 discovered the homonymous excretory duct of the parotid gland. His anatomic studies eventually brought him to Florence, as court physician to Grand Duke Ferdinand II. There he was converted to Catholicism by a nun and became a priest. In his new devotion (and much to the dismay of his scientific colleagues), he completely abandoned science and spent the rest of his life ministering to Roman Catholics in northern Germany. His homonymous ducts are often called Steno’s ducts, from the Latinized version of Stensen into Nicolaus Stenonis, or, more simply, Steno.

62 What are the two most common causes of white spots in the oral mucosa?

Thickening of oral mucosa: This is the most common cause of oral white spots. It is usually due to recurrent trauma, such as biting of the sides of the mouth, and may manifest as a horizontal white line (linea alba in Latin) in the buccal mucosa, stretching between Stensen’s duct and the angle of the mouth. It is created by the juxtaposition of upper and lower teeth. It is also called occlusal (or bite) line. Whitish thickenings of buccal mucosa also can occur near broken teeth or ill-fitting dentures.

Thickening of oral mucosa: This is the most common cause of oral white spots. It is usually due to recurrent trauma, such as biting of the sides of the mouth, and may manifest as a horizontal white line (linea alba in Latin) in the buccal mucosa, stretching between Stensen’s duct and the angle of the mouth. It is created by the juxtaposition of upper and lower teeth. It is also called occlusal (or bite) line. Whitish thickenings of buccal mucosa also can occur near broken teeth or ill-fitting dentures.

Squamous cell carcinoma: The second most common cause of oral white spots, referred to in the past as leukoplakia (Fig. 6-6).

Squamous cell carcinoma: The second most common cause of oral white spots, referred to in the past as leukoplakia (Fig. 6-6).

Figure 6-6 Squamous cell carcinoma presenting as leukoplakia with erythematous and verrucous areas.

(From Sonis ST: Dental Secrets, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Hanley & Belfus, 1999.)

Less common causes of white spots in the oral mucosa include:

63 What is hairy leukoplakia?

A distinctive lesion of the lateral aspects of the tongue and, occasionally, of the buccal mucosa of the cheeks (see also question 100).

72 What features of a white lesion increase its chance of being malignant?

Being palpable, indurated, bleeding, and associated with a concurrent ulcer (see Fig. 6-6). The risk is even higher in patients with satellite lymphadenopathy.

Being palpable, indurated, bleeding, and associated with a concurrent ulcer (see Fig. 6-6). The risk is even higher in patients with satellite lymphadenopathy.

Having concomitant risk factors for malignancy, such as the past or present use of ethanol or tobacco (smoking and chewing). Of interest, in a large review of oropharyngeal carcinomas, neoplastic lesions were more frequently red than white (64% versus 11%). Thus, erythroplasia rather than leukoplakia could be a better clue to a diagnosis of malignancy.

Having concomitant risk factors for malignancy, such as the past or present use of ethanol or tobacco (smoking and chewing). Of interest, in a large review of oropharyngeal carcinomas, neoplastic lesions were more frequently red than white (64% versus 11%). Thus, erythroplasia rather than leukoplakia could be a better clue to a diagnosis of malignancy.

73 List the causes of pigmented spots in the oral mucosa.

Amalgam tattoo (blackish-grayish stain in the buccal mucosa, adjacent to an area of tooth restoration; caused by accidental mucosal exposure to dental amalgam)

Amalgam tattoo (blackish-grayish stain in the buccal mucosa, adjacent to an area of tooth restoration; caused by accidental mucosal exposure to dental amalgam)

Hemochromatosis (bluish-gray pigmentation of the hard palate and, to a lesser degree, of the gums; seen in 15–25% of patients with hemochromatosis)

Hemochromatosis (bluish-gray pigmentation of the hard palate and, to a lesser degree, of the gums; seen in 15–25% of patients with hemochromatosis)

Malignant melanoma (pigmented lesion with irregular borders; often palpable and ulcerated)

Malignant melanoma (pigmented lesion with irregular borders; often palpable and ulcerated)

Melanoplakia (black spots in Greek); consists of one or more pigmented patches on the buccal mucosa of healthy, dark-skinned individuals; normal and of little clinical significance

Melanoplakia (black spots in Greek); consists of one or more pigmented patches on the buccal mucosa of healthy, dark-skinned individuals; normal and of little clinical significance

77 How do you distinguish Peutz-Jeghers syndrome from plain freckling?

The pigmented spots of Peutz-Jeghers are not only more prominent on the lips than the surrounding skin but also are present in the buccal mucosa. This is not the case with freckling (see question 113).

80 Describe the lesions of erythema migrans.

They are multiple, flat, irregularly shaped red patches with raised white rims, usually located on the buccal mucosa, ventral tongue, and gum. Erythema migrans is often associated with a geographic tongue, which is in fact also referred to as erythema migrans lingualis (i.e., benign migratory glossitis, geographic tongue. See question 97).

84 What are aphthous ulcers?

Minor aphthae are extremely common and usually involve the labial or buccal mucosa, soft palate, tongue, and mouth floor. They are usually shallow, <1 cm in diameter, and either isolated or multiple.

Minor aphthae are extremely common and usually involve the labial or buccal mucosa, soft palate, tongue, and mouth floor. They are usually shallow, <1 cm in diameter, and either isolated or multiple.

Major aphthae are instead large and deep. Hence, they often heal with scarring.

Major aphthae are instead large and deep. Hence, they often heal with scarring.

Herpetiform aphthae tend to be more numerous and vesicular in morphology.

Herpetiform aphthae tend to be more numerous and vesicular in morphology.

85 How do you differentiate between a canker and a chancre?

Canker (Middle English term for a malignant, spreading, invading, and ominous lesion) has now become a modern colloquialism for canker sore, a quite painful but entirely benign aphthous ulcer (previously discussed in question 83).

Canker (Middle English term for a malignant, spreading, invading, and ominous lesion) has now become a modern colloquialism for canker sore, a quite painful but entirely benign aphthous ulcer (previously discussed in question 83).

Chancre (an Old French term, subsequently adopted by modern French language) still refers to the much more serious, painless ulcer of primary syphilis.

Chancre (an Old French term, subsequently adopted by modern French language) still refers to the much more serious, painless ulcer of primary syphilis.

C. Tongue

93 Summarize the abnormalities of the tongue.

| Atypical Tongues |

| Macroglossia |

| Scrotal tongue |

| Hairy tongue |

| Geographic tongue |

| Median rhomboid glossitis |

| Tongue-tie |

| Discolorations |

| White Tongue |

| Geographic tongue |

| White hairy tongue (= hairy leukoplakia) |

| Oral thrush |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Red Tongue |

| Atrophic glossitis |

| Black Tongue |

| Hairy tongue |

| Use of charcoal for gastrointestinal decontamination |

| Ingestion of dark-colored candy or black licorice |

| Ingestion of bismuth-containing products (Pepto-Bismol) |

| Colonization by Aspergillus niger |

97 What is a geographic tongue?

A benign inflammatory condition, often referred to as benign migratory glossitis (i.e., erythema migrans lingualis; see also question 80). This is characterized by multiple, smooth, red, and glossy patches of glossitis, each surrounded by a serpiginous rim of a whitish/hyperkeratotic border (Fig. 6-7). The patches resemble the islands of an archipelago (hence, the nickname of geographic), and primarily affect the tongue’s dorsum, even though they may often extend to the lateral borders. Histologically, they are caused by atrophy of the filiform papillae and may even wax and wane with time. Hence, the adjective of migratory. Eventually, they resolve spontaneously only to reappear at different sites (if lesions occur in other mucosae, the condition is instead termed erythema migrans). A geographic tongue often runs in families and is relatively common, being present in up to 3% of the general population. It has no racial or ethnic predilection, but does affect adults more than children and women more than males (2:1). In fact, exacerbations have often been linked to hormonal factors. Still, unlike atrophic glossitis, a geographic tongue is not associated with nutritional deficiency, but is instead idiopathic. A psychosomatic relation has even been suggested. Histologically, lesions are quite similar to those of psoriasis, or to the mucocutaneous presentations of Reiter’s syndrome. In fact, a geographic tongue is four times more prevalent in psoriatics. It remains, however, asymptomatic (although some patients report increased sensitivity to hot and spicy foods), quite benign, and usually self-limited. Differential diagnosis includes candidiasis, contact stomatitis, chemical burns, lichen planus, and psoriasis. Given the typical clinical presentation, reassurance (and not biopsy) is the best management.

100 What is a white hairy tongue (hairy leukoplakia)?

A serious condition characterized by multiple white, warty, corrugated, and painless plaques, full of hair-like projections of keratin growth (Fig. 6-8). These are usually on the lateral margins of the tongue, but can occasionally involve the buccal mucosa of the cheeks and other oral sites. Unlike thrush, hairy leukoplakia cannot be scraped off. The lesion is typically associated with HIV infection, even though it also can occur in severely immunocompromised organ transplants. Caused by the Epstein-Barr virus, it is neither painful nor dangerous. In fact, most patients are unaware of it. May even regress in response to antiviral therapy, yet it does carry a worse prognosis for HIV progression. Clinical appearance is distinctive enough to yield a diagnosis. When in doubt, biopsy.

102 What causes atrophic glossitis?

Usually, a profound deficiency of B-complex vitamins, such as niacin, pyridoxine, thiamine, riboflavin, folate, and B12. Physical examination may help differentiating folate from B12 deficiency by testing of proprioceptive sensation. In folate deficiency, the patient has glossitis but normal proprioception; in B12 deficiency (and, therefore, in pernicious anemia), the glossitis is instead accompanied by abnormal proprioception. Other causes of glossitis include regional enteritis, iron-deficiency anemia, alcoholism, severe malnutrition (protein-calorie), and malabsorption. Glossitis often presents with cheilitis (see question 108).

103 What causes palpable lingual nodules and papules?

Many entities, with most being variants of normalcy, but some being harbingers of malignancy.

Circumvallate papillae: These may become so prominent at times to appear suspicious. Easily visualized by having the patient protrude the tongue, they are entirely normal.

Circumvallate papillae: These may become so prominent at times to appear suspicious. Easily visualized by having the patient protrude the tongue, they are entirely normal.

Lingual thyroid: Another benign but more unusual entity, this is the vestigial remnant of the thyroid’s embryologic site, before the gland migrated down to the front of the neck during the first trimester of pregnancy (failure to migrate causes a lingual thyroid; excessive migration causes instead a mediastinal/substernal thyroid). It presents as a smooth, round, and red midline nodule at the base of the tongue. Lingual thyroids are four times more common in females, typically asymptomatic, and rarely >1 cm (even though at times they may exceed 4 cm). Larger lesions may interfere with swallowing and respiration, and even present with a typical “hot potato speech.” Also, up to 70% of patients may have hypothyroidism, and 10% cretinism. A lump of this sort in a teenage or young adult should never be removed, but instead diagnosed by confirming iodine uptake on radionuclide scan.

Lingual thyroid: Another benign but more unusual entity, this is the vestigial remnant of the thyroid’s embryologic site, before the gland migrated down to the front of the neck during the first trimester of pregnancy (failure to migrate causes a lingual thyroid; excessive migration causes instead a mediastinal/substernal thyroid). It presents as a smooth, round, and red midline nodule at the base of the tongue. Lingual thyroids are four times more common in females, typically asymptomatic, and rarely >1 cm (even though at times they may exceed 4 cm). Larger lesions may interfere with swallowing and respiration, and even present with a typical “hot potato speech.” Also, up to 70% of patients may have hypothyroidism, and 10% cretinism. A lump of this sort in a teenage or young adult should never be removed, but instead diagnosed by confirming iodine uptake on radionuclide scan.

Lingual tonsils: Reddish and smooth-surfaced nodules/papules on the posterior lateral border of the tongue in the foliate papilla area. Normal, albeit hypertrophic, lymphatic tissue.

Lingual tonsils: Reddish and smooth-surfaced nodules/papules on the posterior lateral border of the tongue in the foliate papilla area. Normal, albeit hypertrophic, lymphatic tissue.

Papilloma: Soft, well-circumscribed, and pedunculated nodule that originates in the lingual mucosa and may achieve relatively large size. Caused by the human papilloma virus.

Papilloma: Soft, well-circumscribed, and pedunculated nodule that originates in the lingual mucosa and may achieve relatively large size. Caused by the human papilloma virus.

Carcinoma: Any nontender, firm, and whitish plaque, papule, or nodule (even ulcer) should be considered neoplastic until proven otherwise. Carcinomas, especially squamous cell, tend to involve the lateral aspects of the tongue; hence, they may be missed by haphazard examinations.

Carcinoma: Any nontender, firm, and whitish plaque, papule, or nodule (even ulcer) should be considered neoplastic until proven otherwise. Carcinomas, especially squamous cell, tend to involve the lateral aspects of the tongue; hence, they may be missed by haphazard examinations.

D. Lips

108 What is the difference between cheilosis and cheilitis?

Cheilosis (cheilos, lip in Greek) is reddening and cracking of one or both angles of the mouth—hence, the term of angular cheilosis, or angular stomatitis. This is usually encountered in edentulous patients with ill-fitting dentures, where it is caused by recurrent leakage of saliva, maceration of surrounding tissues (hence, the French term perlèche, excessive licking), and superimposed infection by endogenous organisms. These include Candida for patients with dentures and S. aureus for dentate individuals. Concomitant nutritional deficiencies (such as B12, pyridoxine, riboflavin, or folate) as well as HIV, iron deficiency anemia. and Plummer-Vinson syndrome, also may contribute to its development.

Cheilosis (cheilos, lip in Greek) is reddening and cracking of one or both angles of the mouth—hence, the term of angular cheilosis, or angular stomatitis. This is usually encountered in edentulous patients with ill-fitting dentures, where it is caused by recurrent leakage of saliva, maceration of surrounding tissues (hence, the French term perlèche, excessive licking), and superimposed infection by endogenous organisms. These include Candida for patients with dentures and S. aureus for dentate individuals. Concomitant nutritional deficiencies (such as B12, pyridoxine, riboflavin, or folate) as well as HIV, iron deficiency anemia. and Plummer-Vinson syndrome, also may contribute to its development.

Cheilitis results instead from accelerated tissue degeneration, usually from excessive exposure to wind, especially sunlight (actinic cheilitis). It is characterized by dry scaling of the lips with painful vertical fissures. These are typically perpendicular to the vermilion border and tend to predominate in the lower lip. Cheilitis is a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma, and also an early sign of Crohn’s disease. Causes are ultraviolet radiation and the same nutritional deficiencies previously listed. Prevention includes use of sun blockers in lipstick and balm.

Cheilitis results instead from accelerated tissue degeneration, usually from excessive exposure to wind, especially sunlight (actinic cheilitis). It is characterized by dry scaling of the lips with painful vertical fissures. These are typically perpendicular to the vermilion border and tend to predominate in the lower lip. Cheilitis is a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma, and also an early sign of Crohn’s disease. Causes are ultraviolet radiation and the same nutritional deficiencies previously listed. Prevention includes use of sun blockers in lipstick and balm.

110 What causes a diffusely enlarged lip?

Other than trauma (i.e., “fat-lip”), the most common cause is angioedema.

E. Gums and Teeth

118 What is the most common cause of a diffuse thickening of the gums? What are the other possible causes?

123 What causes tooth loss?

Not so much tooth extraction (or fracture) but rather:

Tooth abrasion: From localized grinding (bruxism, from the Greek word brucho, or “grinding”) and recurrent trauma due to toothpicks or pipes, which may notch the occlusal surface of the affected tooth.

Tooth abrasion: From localized grinding (bruxism, from the Greek word brucho, or “grinding”) and recurrent trauma due to toothpicks or pipes, which may notch the occlusal surface of the affected tooth.

Tooth attrition: From decades of mastication, resulting in diffuse wearing down of teeth—as if they had been filed (like Nurse Diesel in Mel Brooks’ High Anxiety). Because of attrition, the yellow-brown dentin becomes surrounded by only a rim of worn-down enamel. Hence, the yellowish hue of the tooth.

Tooth attrition: From decades of mastication, resulting in diffuse wearing down of teeth—as if they had been filed (like Nurse Diesel in Mel Brooks’ High Anxiety). Because of attrition, the yellow-brown dentin becomes surrounded by only a rim of worn-down enamel. Hence, the yellowish hue of the tooth.

Tooth erosion: Diffuse wearing down of teeth caused by recurrent exposure to corroding chemicals. It is often seen in people who consume large quantities of freshly squeezed citrus fruits or even sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages. It is, however, much more common in bulimic patients, whose enamel is exposed to regurgitated gastric acid, causing dental erosion in two thirds of subjects. These usually affect the posterior (lingual) aspect of the teeth, particularly the incisors. Similar erosions also may occur in nonbulimic patients because of simple acid reflux disease. Thinning of the enamel results in exposure of the yellow-brown dentin, with yellow discoloration of teeth and cavity formation.

Tooth erosion: Diffuse wearing down of teeth caused by recurrent exposure to corroding chemicals. It is often seen in people who consume large quantities of freshly squeezed citrus fruits or even sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages. It is, however, much more common in bulimic patients, whose enamel is exposed to regurgitated gastric acid, causing dental erosion in two thirds of subjects. These usually affect the posterior (lingual) aspect of the teeth, particularly the incisors. Similar erosions also may occur in nonbulimic patients because of simple acid reflux disease. Thinning of the enamel results in exposure of the yellow-brown dentin, with yellow discoloration of teeth and cavity formation.

128 What nonpathologic factors may cause halitosis?

129 What are the pathologic causes of halitosis?

Pathologic causes may be either local or systemic. The most common local causes include:

Disorders of the oral cavity, such as retained food, stomatitis, glossitis, periodontal disease, poorly cleaned dentures, and even decreased saliva with development of dry mouth (xerostomia)

Disorders of the oral cavity, such as retained food, stomatitis, glossitis, periodontal disease, poorly cleaned dentures, and even decreased saliva with development of dry mouth (xerostomia)

Disorders of the nose and sinuses, such as atrophic rhinitis, chronic sinusitis, nasal septal perforation, ozena (an atrophic disease involving the nose and turbinates), and retained foreign bodies (especially in children)

Disorders of the nose and sinuses, such as atrophic rhinitis, chronic sinusitis, nasal septal perforation, ozena (an atrophic disease involving the nose and turbinates), and retained foreign bodies (especially in children)

Disorders of the tonsils and pharynx, such as recurrent infections of the tonsils and adenoids, pharyngitis, and especially Zenker’s diverticulum

Disorders of the tonsils and pharynx, such as recurrent infections of the tonsils and adenoids, pharyngitis, and especially Zenker’s diverticulum

Disorders of digestive organs (esophagus, stomach, and small intestines), such as achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux

Disorders of digestive organs (esophagus, stomach, and small intestines), such as achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux

Disorders of the lungs, such as anaerobic lung abscesses, bronchiectasis, pneumonia, and empyema

Disorders of the lungs, such as anaerobic lung abscesses, bronchiectasis, pneumonia, and empyema

Systemic conditions presenting with a particular odor of the breath include:

1 Benbadis SR, Wolgamuth BR, Goren H, et al. Tongue-biting in seizures. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:2346-2349.

2 Cunha BA. Crimson crescents and chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:347.

3 Drinka PJ, Langer E, Scott L, Morroe F. Laboratory measurements of nutritional status as correlates of atrophic glossitis. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:137-140.

4 Ebell MH, Smith MA, Barry HC, et al. Does this patient have strep throat? JAMA. 2000;284:2912-2918.

5 Eisenberg E, Krutchkoff D, Yamase H, et al. Incidental oral hairy leukoplakia in immunocompetent persons: A report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:332-333.

6 Friedman IH. Say “ah” [letter]. JAMA. 1984;251:2086.

7 Johnson BE. Halitosis, or the meaning of bad breath. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:649-656.

8 Jones RR, Cleaton-Jones P. Depth and area of dental erosions, and dental caries, in bulimic women. J Dent Res. 1989;68:1275-1278.

9 Kidd DA,: Collins Gem Dictionary: Latin-English, English-Latin. London;Williams Collins Sons: 1979 As quoted in Sapira JD: The Art and Science of Bedside Diagnosis. Baltimore: Urban & Schwarzenberg, 1990.

10 Mashberg A, Feldman LJ. Clinical criteria for identifying early oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma: Erythroplasia revisited. Am J Surg. 1988;156:273-275.

11 Moore MJ. Say “ah” [letter]. JAMA. 1984;251:2086.

12 Redman RS, Vance FL, Gorlin RJ. Psychological component in the etiology of the geographic tongue. J Dent Res. 1966;45:1403-1408.

13 Roenigk RK. CO2 laser vaporization for treatment of rhinophyma. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1987;62:676-680.

14 Savitt JN. “Say ae.”. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:1068-1069.

15 Schroeder PL, Filler SJ, Ramirez B, et al. Dental erosion and acid reflux disease. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:809-815.