CHAPTER 9 Nontrauma Abdomen

BOWEL DISEASE

Diseases Causing Bowel Obstruction

Mechanical Small Bowel Obstruction

Imaging Findings

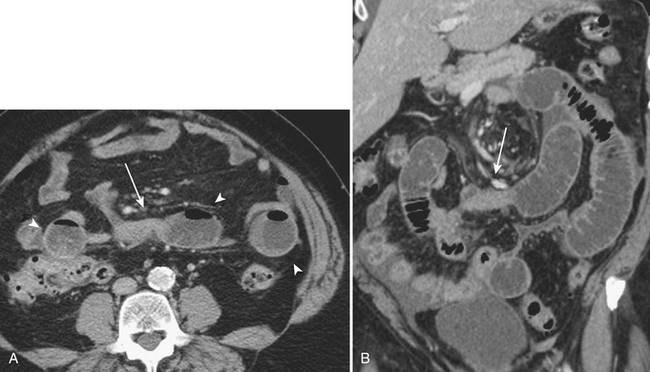

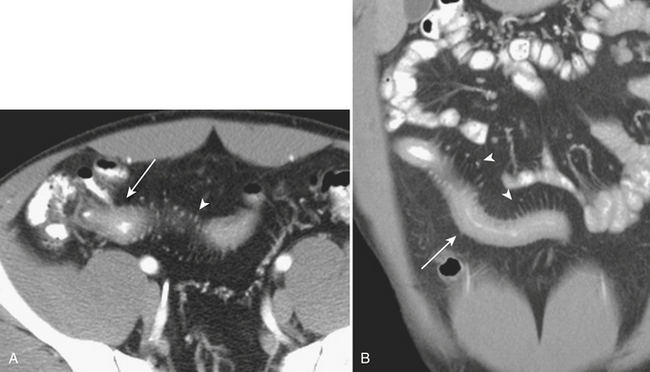

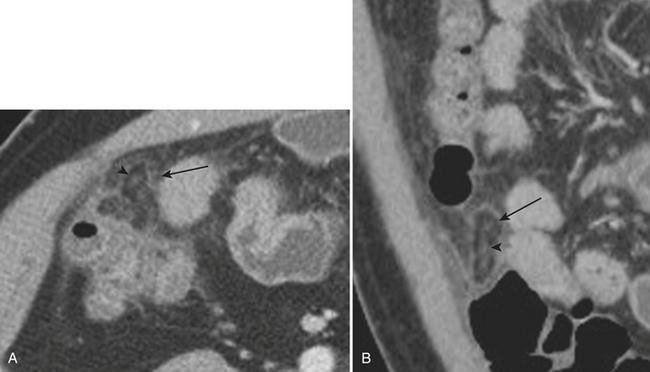

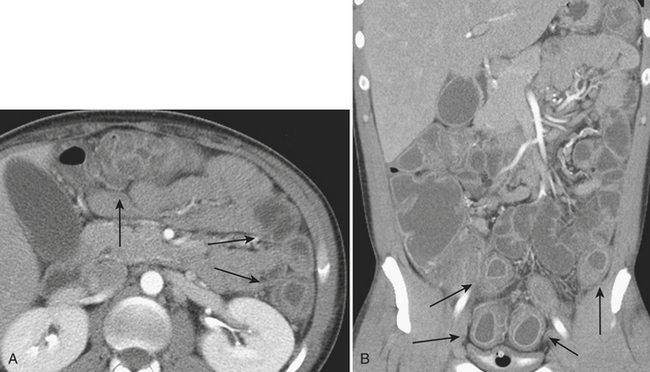

CT is often used for further characterization in patients with suspected mechanical small bowel obstruction. Similar to radiography, the diagnosis on CT involves identifying distended air- and fluid-filled loops of small bowel, typically greater than 3 cm in diameter. The small bowel “feces” sign, which is the presence of air and particulate matter within loops of small bowel resembling feces, is a finding commonly seen in small bowel obstruction and is helpful in its diagnosis by suggesting increased bowel transit time. Often, CT allows for the diagnosis of the exact point of transition between distended loops of small bowel and the more normal collapsed loops of small bowel and possibly for identifying the underlying cause of the small bowel obstruction (Fig. 9-1).

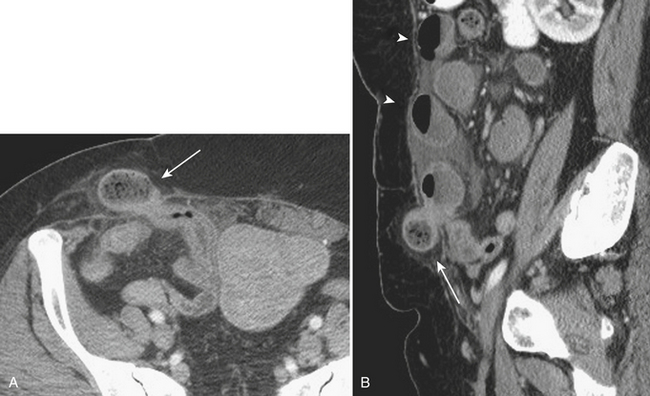

Hernias are a second common cause of small bowel obstruction. CT is used to further characterize these hernias, which may be complex in some cases. Common types of hernias include inguinal hernias, umbilical hernias, incisional hernias, and Spigelian hernias in the location of the linea semilunaris (Fig. 9-2). Among less common causes of mechanical small bowel obstruction are internal hernias, including congenital or surgically acquired rents within the mesentery as well as a myriad of other named internal hernias that have been described. CT images including multiplanar reformations are often employed to further characterize these complex hernias.

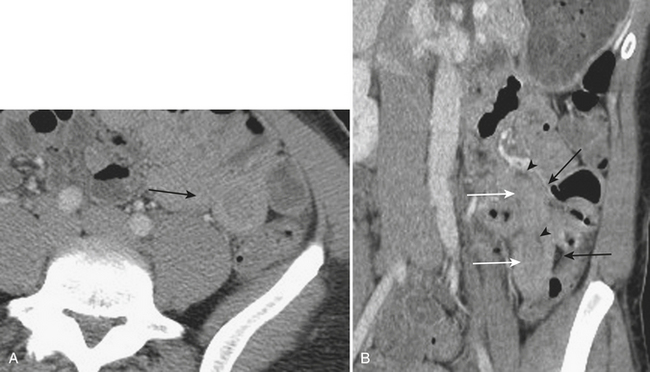

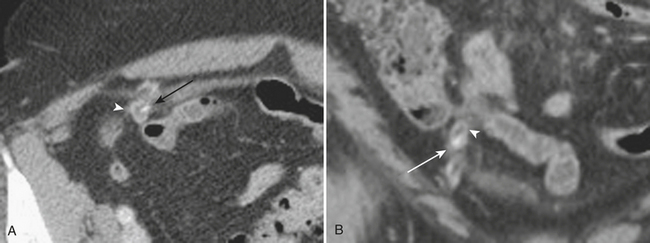

Although more common in the pediatric population, small bowel intussusception may also be seen in adults and can cause obstruction of small bowel loops proximally. In adults, one must always consider the possibility of a lead point such as a neoplasm. Other causes of small bowel intussusception in adults include Meckel’s diverticulum and postoperative states especially after gastric bypass. With the increasingly widespread use of CT, transient small bowel intussusceptions are more commonly seen. One may suggest the diagnosis of a transient intussusception based on location and length, as well as the absence of proximal small bowel dilatation (Fig. 9-3).

Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases

Infectious Small Bowel Enteritis

Imaging Findings

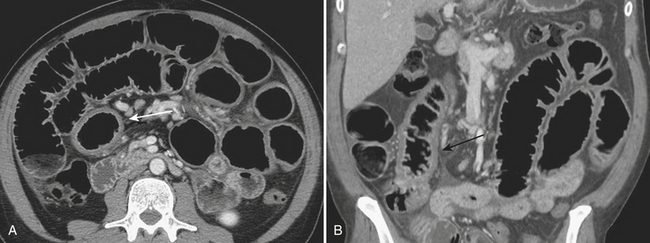

CT imaging, when acquired, is also often nonspecific and may demonstrate mild to moderate small bowel dilatation and mural thickening (Fig. 9-4). Often, the small bowel is diffusely affected; however, certain infections may present in more specific locations such as the proximal small bowel in cases of giardiasis. In the immunocompromised host, a myriad of other infectious etiologies should be considered, as noted above. Typically, nonspecific small bowel wall thickening and mucosal irregularity are identified in cases of cytomegalovirus and cryptosporidium. In patients affected by Mycobacterium avium intracellulare, hepatic and splenic enlargement, jejunal wall thickening, and enlarged soft tissue attenuation or, less commonly but more characteristically, low-attenuation lymphadenopathy are described.

Crohn’s Disease, Small Bowel

Imaging Findings

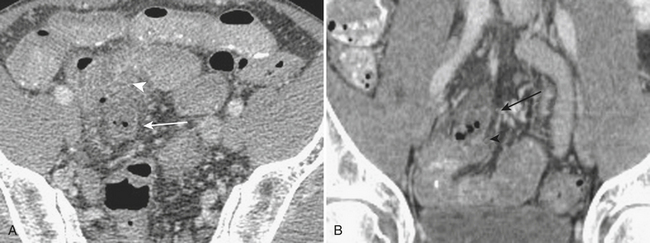

The manifestations of Crohn’s disease of the small bowel typically demonstrate nonspecific CT signs of inflammation such as mural thickening. However, findings more specific are often identified. These include isolation to the terminal ileum, hypervascularity and prominence of the vasa recta, the “comb” sign, increased mesenteric fat surrounding loops of small bowel, and “creeping” fat, as well as intra-abdominal fistulae and abscesses (Fig. 9-5).

Small Bowel Diverticulitis

Imaging Findings

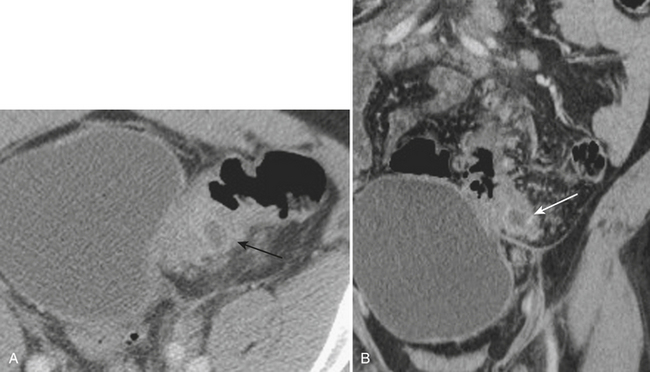

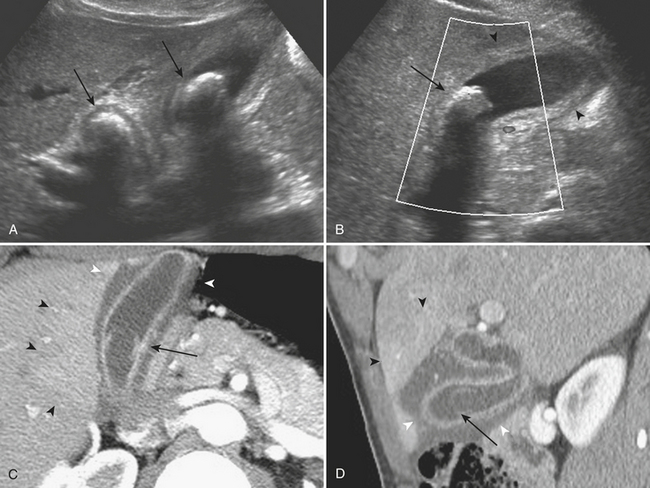

Meckel’s diverticulitis may be diagnosed by CT. A Meckel’s diverticulum is evident as a blind-ending pouch of variable length containing fluid, air, or particulate debris, often located near the midline but seen anywhere from the right lower quadrant to the mid-abdomen. When the diverticulum is inflamed, mural thickening and surrounding inflammatory stranding may be identified (Fig. 9-6). This might be complicated by frank perforation, possibly yielding an intra-abdominal abscess. In cases of diverticulitis unrelated to Meckel’s diverticulum, CT demonstrates focal luminal outpouchings with surrounding inflammatory changes. Again, gross perforation with abscess formation may also be seen.

Appendicitis

Imaging Findings

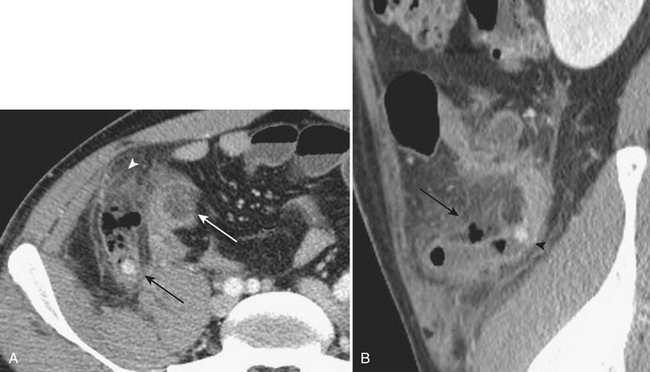

When the ultrasound results are equivocal or the appendix is not visualized, CT is often employed in patients with suspected appendicitis. In older or significantly obese patients, CT may be the initial imaging examination. CT has been shown to have a very high diagnostic accuracy in the diagnosis of appendicitis. In those patients with appendicitis, the appendix appears enlarged, often with surrounding inflammatory changes, including the free intraperitoneal fluid. When present, appendicoliths are readily identified on CT (Fig. 9-7). There is a large variety in the diameter of the appendix in normal patients, with sizes ranging up to 1 cm. However, mean values range between 5 and 7 mm depending on whether or not the appendix is distended with air. Therefore, in a patient with an appendix measuring slightly greater than the standard cutoff value of 6 mm, secondary signs of inflammation should be sought, such as hyperenhancement, periappendiceal fat stranding or fluid, fascial thickening, or edema at the origin of the appendix as evidenced by thickening of the adjacent cecum, the so-called “arrowhead” sign (Fig. 9-8). Filling of the appendix by orally or rectally introduced positive contrast material is a useful means of excluding obstruction of the appendix and, therefore, acute appendicitis. When the appendix is not visualized, this finding, in the absence of right lower quadrant inflammation, carries a high negative predictive value of appendicitis.

Epiploic Appendagitis

Imaging Findings

Given the increasingly routine use of CT imaging in patients with abdominal pain, the imaging manifestations of epiploic appendagitis have been well described. The characteristic imaging findings include an ovoid lesion containing fat, abutting the colon, with surrounding inflammatory stranding (Fig. 9-9). A central high-attenuation focus has been described and is thought to be related to a thrombosed vein. Although helpful when seen, the absence of this finding does not exclude the diagnosis.

Diverticulitis

Imaging Findings

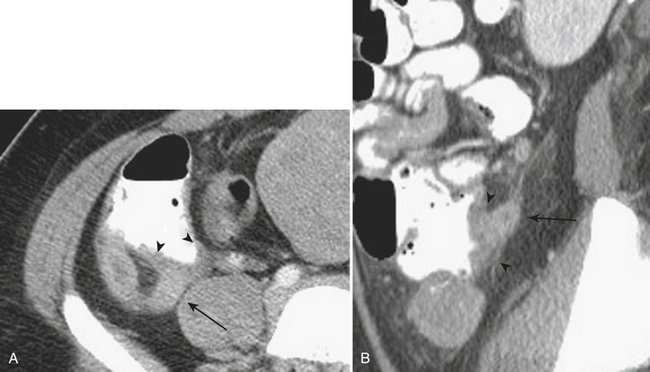

Multiple complications are associated with acute diverticulitis including intramural sinus tracts or abscess, as well as extracolonic phlegmon or abscess formation (Fig. 9-10). Frank perforation with gross free intraperitoneal air may also be encountered in patients with diverticulitis. Other complications include the formation of fistulae, most commonly colovesicular, as well as colovaginal, coloenteric, and colouterine. In those patients with a CT diagnosis of diverticulitis, follow-up colonoscopy is normally advised to rule out underlying malignancy masquerading as diverticulitis.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Colon

Imaging Findings

Typically, in patients presenting acutely, a CT scan is acquired in the emergency department setting. Crohn’s disease demonstrates bowel wall thickening in the affected segments, which are most commonly right-sided; diffuse colitis may also be seen, although isolated left-sided involvement with Crohn’s disease is atypical (Fig. 9-11). Ulcerative colitis, unlike Crohn’s disease, demonstrates contiguous involvement of the bowel from the rectum proximally. Therefore, the CT findings are usually isolated to the left side. The bowel wall may demonstrate stratification, also known as the “water halo” sign, in which the bowel wall consists of two or three symmetrically thickened layers. In the case of three symmetrically thickened layers, also known as the “target” sign, the inner hypoattenuating layer is thought to represent edema within the submucosa. In patients with chronic inflammation, as in Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, a pattern known as the “fat halo” sign may be seen in which there is three-layer stratification with the middle layer demonstrating fat attenuation (Fig. 9-12). The finding of a “fat halo” sign is more commonly associated with ulcerative colitis. Although these are nonspecific signs, taken in context with the remainder of the imaging findings as well as the clinical presentation, they may suggest a potential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Also, hyperenhancement of the bowel after contrast administration is useful in differentiating between chronically thickened loops of bowel secondary to fibrosis and those with active inflammation.

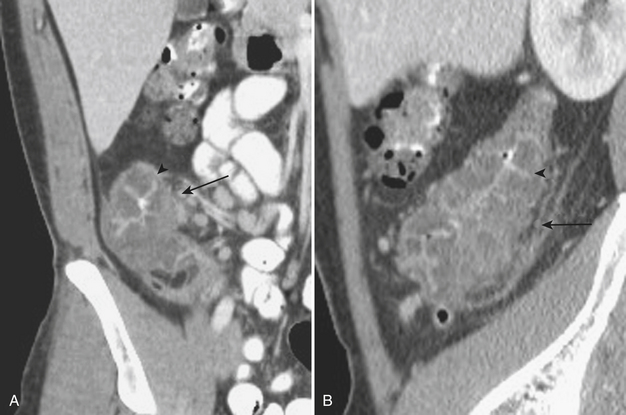

Abscess and phlegmon formation are commonly encountered complications in patients with Crohn’s disease given its transmural nature. Abscesses can be successfully managed percutaneously to avoid unnecessary surgery. Another complication given the transmural extent of Crohn’s disease is the formation of sinus tracts and fistulae. Common fistulae include enteroenteric and enterocolonic as well as fistulae within the urinary system (Fig. 9-13). Other commonly encountered fistulae are perianal and enterocutaneous fistulae. Although less common, fistulas may also be encountered in patients with ulcerative colitis.

Infectious Colitis

Imaging Findings

The CT imaging appearances of the infectious colitides are nonspecific, and there is considerable overlap among the various etiologies. The CT findings typically demonstrate pancolitis with marked colonic wall thickening, approaching the severity of Crohn’s disease (Fig. 9-14). The “accordion” sign may be seen as edematous haustral folds, separating the oral-contrast-filled lumen into narrow ridges, similar in appearance to an accordion. Although originally described as specific for patients with pseudomembranous colitis, this finding may be seen in any cause of severe colonic wall edema.

Foreign Bodies

Imaging Findings

In patients with known foreign body ingestion, CT is infrequently employed for localization and evaluation of potential complications. Also, in patients with bowel perforation, and even in cases of obstruction, one may consider the possibility of a foreign body as the underlying etiology. The foreign bodies, depending on the composition, may also be subtle on CT (Fig. 9-15). However, when complications ensue, these may be helpful in localizing the foreign body. In cases of anally introduced foreign bodies, CT is particularly useful in identifying rectal injuries as evidenced by rectal wall thickening, surrounding fat stranding, and possibly free extra- or intraperitoneal air. CT is also, rarely, employed in the evaluation of illicit narcotic ingestion.

PANCREATICOBILIARY DISEASE

Acute Pancreatitis

Imaging Findings

Although imaging is not typically acquired in uncomplicated cases of acute pancreatitis, it does play a significant role in this disease process. Initial plain radiographs in patients with acute pancreatitis may demonstrate local ileus secondary to inflammation, the so-called “sentinel loop” sign. Other findings may include the visualization of calcifications within the pancreatic parenchyma in those patients presenting with acute on chronic pancreatitis (Fig. 9-16). The main role of ultrasonography in acute pancreatitis is in those patients with suspected gallstone pancreatitis; ultrasound may be used for confirmation of the presence of gallstones. Ultrasound may also be able to identify evidence of choledocholithiasis, although the examination of the distal aspect of the common duct is often limited on ultrasonography. Ultrasound may demonstrate the findings of acute pancreatitis as it affects the pancreatic parenchyma and surrounding peripancreatic tissues. Often, diffuse or focal enlargement of the pancreas is identified along with evidence of edema seen as abnormally hypoechoic parenchyma. Peripancreatic fluid may also be identified on ultrasonography. Although not required for the diagnosis of uncomplicated acute pancreatitis, when seen, typical CT findings include focal or diffuse enlargement of the gland as well as edema, identified as abnormal hypoattenuation of the parenchyma and stranding along with free fluid in the peripancreatic tissues (Fig. 9-17).

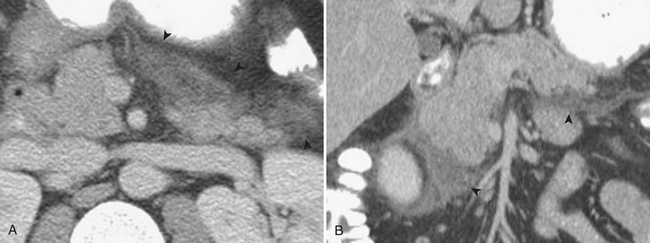

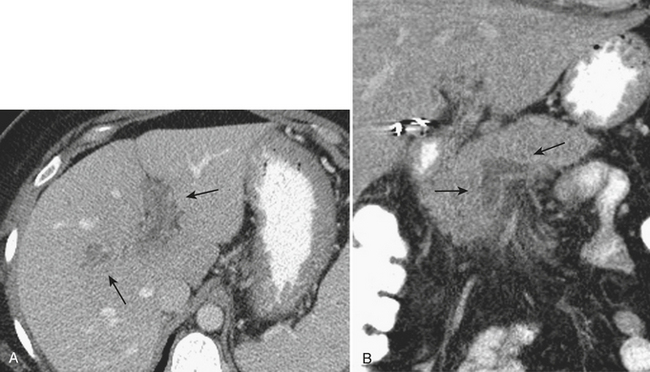

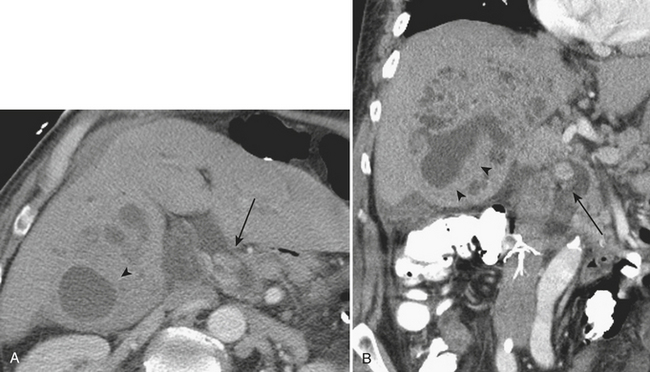

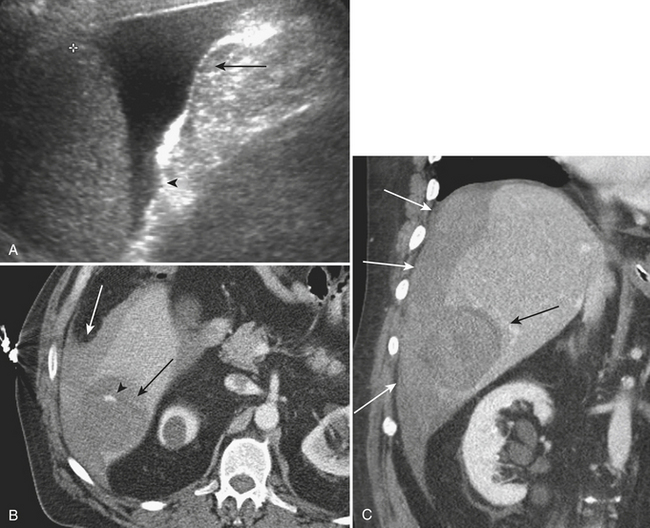

Other complications that may be identified by CT in patients with acute pancreatitis include sequelae of injury to the splenic vasculature. These include splenic vein thrombosis, splenic infarction or subcapsular hemorrhage, and splenic artery pseudoaneurysm formation (Fig. 9-18). Pseudoaneurysms may communicate, rarely, with the pancreatic duct in a condition known as hemosuccus pancreaticus, in which bleeding occurs into the pancreatic duct and out of the ampulla of Vater to exit into the duodenum (Fig. 9-19). Treatment of splenic artery pseudoaneurysms may be successfully accomplished via transcatheter embolization, as well as by percutaneous techniques.

Cholecystitis

Imaging Findings

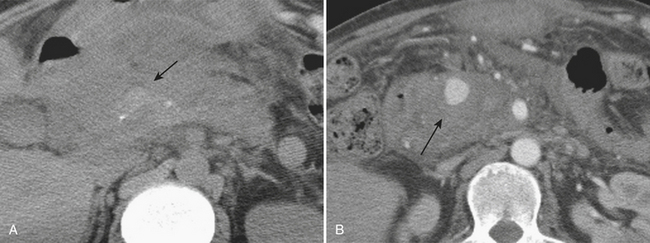

In patients with suspected acute cholecystitis, ultrasonography is typically employed in the initial diagnostic evaluation. The ultrasound criteria for diagnosing acute cholecystitis include evidence of gallstones, gallbladder wall thickening, and distention, as well as elicitation of a sonographic Murphy’s sign. To elicit a sonographic Murphy’s sign, the patient is asked to breathe out with the ultrasound probe placed over the right upper quadrant. Upon the subsequent inspiration, if the patient halts the inhalation as the gallbladder passes beneath the ultrasound probe and is visualized, it is considered to be a positive sonographic Murphy’s sign (Fig. 9-20). The normal gallbladder wall is typically 2 to 3 mm in diameter; gallbladder wall thickness greater than 3 mm is considered abnormal in patients with suspected acute cholecystitis. A caveat in evaluating gallbladder wall thickness is that there are numerous causes of a thickened gallbladder wall. Gallbladder wall thickening can be seen in common systemic diseases such as cirrhosis, acute hepatitis, hypoproteinemia, renal failure, and congestive heart failure. Often, in patients with gallbladder wall thickening secondary to acute cholecystitis, areas of lucency corresponding to subserosal edema may be seen within the wall. Finally, in patients with acute cholecystitis, the gallbladder is typically significantly distended secondary to obstruction. A measurement of greater than 10 cm in the long axis of the gallbladder or 5 cm in the transverse or anterior-posterior axis is normally used to signify abnormal distention. Complications include gangrenous cholecystitis, which may demonstrate a striated pattern of gallbladder wall thickening with alternating hyperechoic and hypoechoic layers. Increasingly specific signs in more severe cases include the presence of sloughed mucosa seen within the gallbladder lumen as demonstrated by thin hyperechoic bands. In some cases of severe cholecystitis, hemorrhage may be present within the lumen, termed hemorrhagic cholecystitis. In these cases, ultrasound commonly demonstrates the findings of gangrene, in addition to nonshadowing intraluminal echoes, which may entirely fill the lumen of the gallbladder. Finally, emphysematous cholecystitis represents a rare but life-threatening complication, often associated with diabetes, in which foci of air are identified within the wall and/or lumen of the gallbladder. On ultrasound, echogenic foci or bands are seen with posterior ring-down artifact, or “dirty shadowing.” Often, the presence of the gas obscures actual visualization of the gallbladder wall. These findings are specific for this life-threatening complication and should be recognized and treated urgently.

CT is often used for patients with nonspecific clinical presentations of abdominal pain or equivocal findings on the initial ultrasound examination. The findings of acute cholecystitis, including its complications, should be recognized on CT. As on ultrasound, CT demonstrates gallbladder wall thickening, pericholecystic fluid, and possibly pericholecystic fat stranding. In most cases, the obstructing gallstone may be identified, although this is less likely on CT than on ultrasound, as discussed above. In those patients who receive intravenous contrast, especially when imaged during an arterial phase of enhancement, there may be evidence of secondary inflammation of the liver around the gallbladder fossa (see Fig. 9-20). This is seen as relative hyperenhancement of this portion of the liver parenchyma. CT may also demonstrate the complications of acute cholecystitis. In those patients with a gangrenous cholecystitis, the most specific CT imaging findings are shown to be direct evidence of the sloughed membranes within the lumen, irregularity of the gallbladder wall, and perforation including pericholecystic abscess. Hemorrhage is also clearly identified on CT, as evidenced by increased attenuation of the intraluminal bile. Finally, emphysematous cholecystitis is also demonstrated on CT by direct evidence of air within the gallbladder wall and/or lumen.

Hepatolithiasis

Imaging Findings

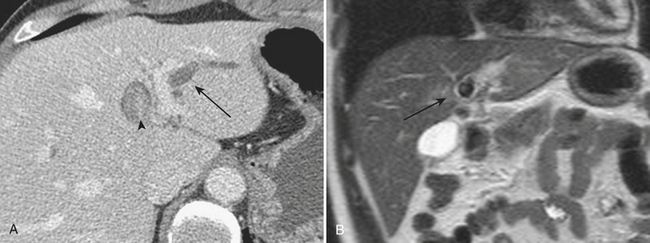

The typical CT findings of hepatolithiasis include direct visualization of the intrahepatic stones, as well as intra- and extrahepatic biliary dilatation and stricture formation (Fig. 9-21). Hepatic parenchymal atrophy may also be identified. During the acute stages, recurrent pyogenic infections demonstrate the typical findings of inflammation on CT, including bile duct wall enhancement and adjacent hepatic parenchymal hyperenhancement. Complications of the acute disease include intrahepatic abscess and biloma formation. The dreaded long-term complication of recurrent pyogenic cholangitis is the development of cholangiocarcinoma. This typically develops in atrophic, stone-containing segments of the hepatic parenchyma and is usually associated with narrowing of the adjacent portal vein. As on ultrasound, the presence of intrabiliary parasites may be directly identified on CT.

DISEASES OF THE LIVER

Focal Hepatic Infections

Imaging Findings

On CT, the abscesses are relatively hypoattenuating with the surrounding liver parenchyma (Fig. 9-22). Often, surrounding, smaller collections are identified in the vicinity of the largest abscess cavity. Hyperenhancement of the surrounding liver parenchyma may be identified, possibly related to local portal venous obstruction secondary to the acute inflammation. As on ultrasound, there may be direct evidence of air within the collection. Complications of liver abscesses, including venous thrombosis, are seen in up to half of patients. The hepatic venous system is affected nearly as often as the portal veins. Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates the nonenhancing hypoattenuating tubular structures of the thrombosed veins.

DISEASES OF THE GENITOURINARY TRACT

Nephrolithiasis

Imaging Findings

Renal stone CT protocols are usually acquired without the use of oral or intravenous contrast, which may obscure the underlying stones. CT has a high diagnostic accuracy in the detection of renal and ureteral calculi and may be used to differentiate among stones of various chemical compositions. Recently, ultra-low-dose CT with radiation dose equivalent to a KUB has been shown to be diagnostically sufficient in evaluating renal and ureteral calculi. Renal stones are most commonly composed of calcium in the form of calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, and calcium urate. Other common stones are struvite, uric acid, and cystine stones. These most common forms of renal stones are all readily identified by routine CT techniques (Fig. 9-23). However, in patients with HIV with a clinical suspicion of nephrolithiasis, protease-inhibitor induced stones, because they are not routinely identified on CT, should be a consideration.

Renal Abscess

Imaging Findings

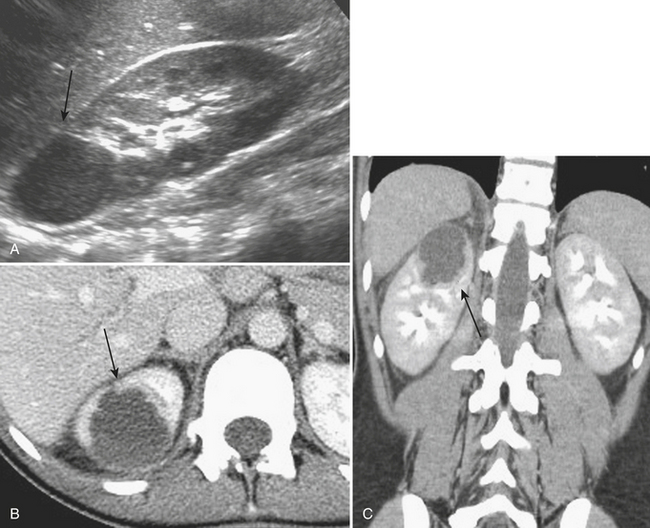

The distinction between a focal renal abscess and acute focal bacterial nephritis has important implications for subsequent management. Renal abscesses usually demonstrate ultrasound findings of a complex, focal, hypoechoic region within the parenchyma, often with internal echotexture but with evidence of increased through-transmission (Fig. 9-24). Focal bacterial nephritis, it has been reported, lacks the increased through-transmission of a renal abscess.

Xanthogranulomatous Pyelonephritis

Imaging Findings

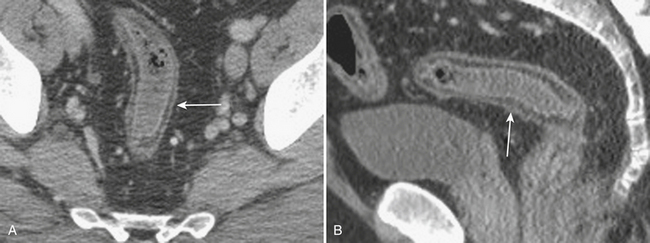

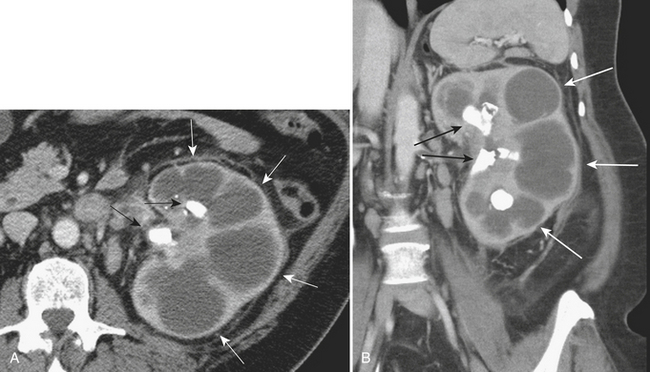

CT demonstrates renal enlargement with fluid-filled cavities replacing the renal parenchyma, often with extension into the perinephric tissues, findings suggestive of XGP. Again, hydronephrosis and renal calculi may be identified in patients with XGP (Fig. 9-25). CT evidence of fistula formation with surrounding tissues including bowel or skin lends credence to a suspected diagnosis of XGP.

DISEASES OF THE SPLEEN

EMERGENT IMAGING FINDINGS

Pneumoperitoneum

Imaging Findings

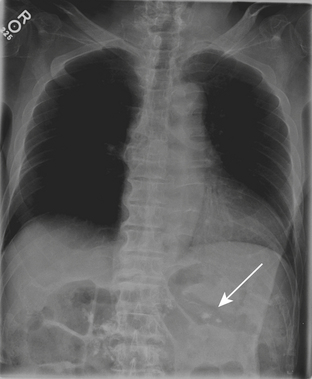

Plain radiographs are often initially employed to detect free intraperitoneal air. Typically, a supine radiograph, in addition to an upright view of the chest, is acquired to evaluate for free intraperitoneal air (Fig. 9-26). Left lateral decubitus views of the abdomen and lateral chest radiographs are further options. In cases of upright radiographs or left lateral decubitus views, acquisition with the central ray of the x-ray beam at the highest level of the peritoneal cavity has been shown to increase sensitivity. Various signs of pneumoperitoneum on abdominal radiographs have been described: they include the Rigler’s sign, in which air is seen on both sides of the bowel wall; the falciform ligament sign, in which air outlines the falciform ligament; the “football” sign, in which air outlines the confines of the peritoneal cavity; the “inverted V” sign, in which air outlines the medial umbilical folds; and the right upper quadrant air sign, in which a focal, typically triangular, collection of gas is seen in the right upper quadrant. At least one of these signs has been reported in slightly more than half of patients with pneumoperitoneum on supine abdominal radiographs. The “cupola” sign of air outlining the median subphrenic space has also been described in the minority of patients with pneumoperitoneum on supine radiographs.

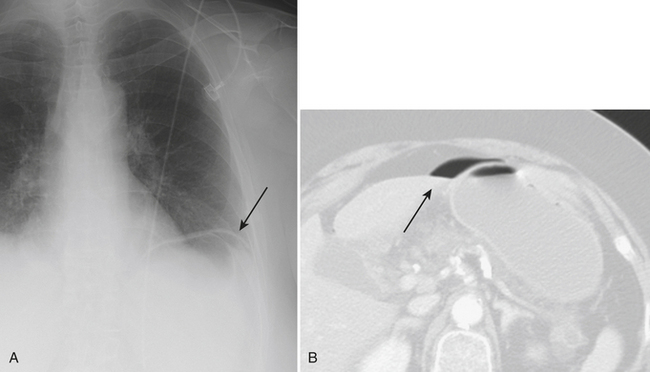

Spontaneous Hemoperitoneum

Spontaneous hemorrhage originating from the liver is usually associated with hepatic tumors, both benign and malignant. As in any splanchnic vascular territory, rupture of hepatic arterial aneurysms or pseudoaneurysms may cause spontaneous hemorrhage. Benign hepatic tumors predisposing to spontaneous hemorrhage include adenomas, while hepatocellular carcinoma and, less likely, metastases account for the malignant etiologies (Fig. 9-27). Spontaneous hemorrhage secondary to other benign hepatic lesions, including focal nodular hyperplasia and cavernous hemangioma, has been described but is much less frequently observed.

Spontaneous Retroperitoneal Hemorrhage

Imaging Findings

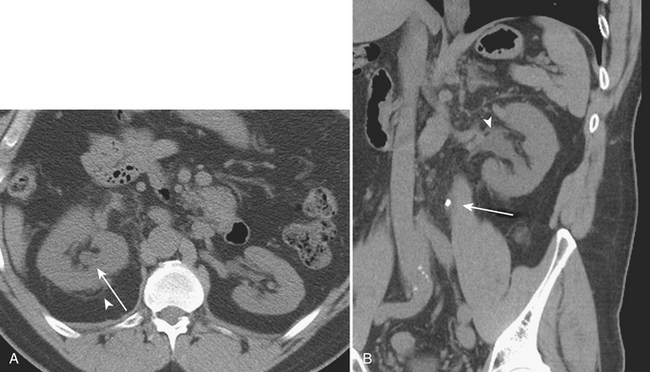

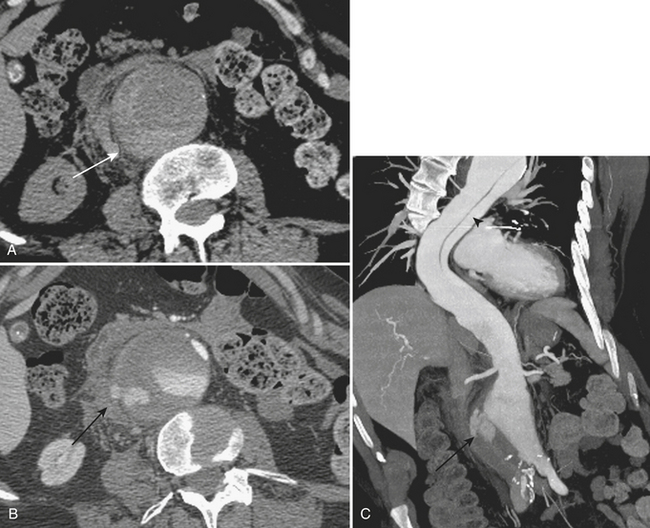

In cases of ruptured AAA, CT is often the first-line imaging modality (Fig. 9-28). CT protocols may include the use of intravenous contrast to evaluate for active extravasation, although unenhanced CT may readily identify cases of AAA rupture. In cases of rupture, CT demonstrates hematoma within the retroperitoneum, contiguous with the aorta. Often, when large, the hemorrhage is identified within multiple retroperitoneal compartments. CT findings that increase the specificity of the diagnosis of ruptured AAA include the “crescent” sign, which refers to hyperattenuating clefts within mural thrombus or the aneurysmal wall itself; a “draped” aorta, which refers to displacement of the aorta onto the spine with lateral “draping” over a vertebral body; discontinuity of the aortic wall; and frank active contrast extravasation. Ruptured AAA represents a surgical emergency that warrants rapid intervention. In cases of renal tumors, specific findings of angiomyolipoma may be identified, such as areas of macroscopic focal fat. However, these can become somewhat obscured by hemorrhage. Also, in cases of renal malignancy, the underlying mass may become obscured and follow-up imaging by CT and MRI may be necessary for identification and characterization of the mass lesion. The spatial resolution and multiplanar capabilities of the current generation of CT scanners offer the ability to accurately diagnose vascular abnormalities secondary to vasculitis, such as the multiple small aneurysms characteristic of PAN. The common causes of spontaneous hemorrhage specific to the pancreas include hemorrhage related to pseudocysts that cause pseudoaneurysm formation in the surrounding arteries secondary to exposure to the various pancreatic enzymes. Other causes include pancreatic malignancies, a rare etiology.

Biliary Obstruction

Imaging Findings

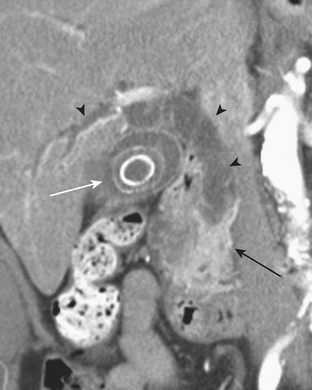

In patients with nonspecific clinical presentation, CT may be initially acquired in cases of biliary obstruction. In cases of intrinsic causes of biliary obstruction, the intraductal filling defect may be identified, such as in the case of choledocholithiasis or neoplasm. In cases of Ascaris lumbricoides infection, the organisms themselves can be visualized as tubular intrahepatic filling defects causing the biliary obstruction. Inflammatory etiologies such as HIV cholangiopathy demonstrate concentric biliary ductal wall thickening resulting in a functional stricture. Similar findings are seen in primary sclerosing cholangitis with areas of beading affecting both intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts. Extrinsic causes of extrahepatic biliary obstruction, while they may be identified on ultrasonography, are typically readily identified on CT and MRI (Fig. 9-29).