CHAPTER 46 NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF BLUNT AND PENETRATING ABDOMINAL INJURIES

BLUNT ABDOMINAL INJURY

Incidence

The incidence of intra-abdominal injury after blunt trauma will vary widely by the patient population, mechanism of injury, and the diagnostic studies employed by the particular center. Approximately 12% of all blunt trauma patients who are screened with computed tomography (CT) have one or more intra-abdominal injuries, with 46% of these being major injuries and 30% requiring surgical or angiographic intervention.1,2 The vast majority of these will be solid organ injuries to the spleen and/or liver, followed by injury to the kidney, mesentery, small bowel, colon, and pancreas. These injuries may be categorized as solid organ (liver, spleen, kidney), hollow viscus (stomach, duodenum, small bowel, colon, ureter, bladder), endocrine (pancreas, adrenal), or vascular. Overall, greater than 95% of these injuries may be managed without surgical intervention and with similar or lower complication rates compared with operative management.3

Mechanism of Injury

Blunt trauma may produce abdominal injuries through a variety of mechanisms, including direct transmission of energy to abdominal structures causing tissue disruption or hollow viscus blowout, shearing from rapid deceleration, direct compression of abdominal organs against the vertebral column, and puncture or laceration from associated rib fracture, spine fracture, or foreign bodies. Although there is not a linear relationship between the degree of force and the amount of abdominal injury, mechanisms involving higher velocity and/or forces will result in more significant and extensive injuries to the abdominal organs. Direct transmission of force to the abdomen will predominantly be absorbed by the large solid organs, such as liver, spleen, and kidney, resulting in parenchymal disruption. Rapid deceleration forces tend to affect fixed or tethered structures such as the kidneys, duodenum, and bowel mesentery, resulting in lacerations or pedicle avulsion. Although seat-belt use has resulted in a decrease in traumatic brain injury and death, there is a twofold increase in the incidence of hollow viscus injuries resulting from the use of seat-belts.3 Organs that are fixed to or in close proximity to the vertebral column may also be injured by direct compression, such as the distal duodenum, pancreas, and great vessels. Fractures of the lower rib cage may directly lacerate upper abdominal structures including the diaphragm, liver, spleen, and kidneys.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of intra-abdominal injury in the blunt trauma patient begins with the primary survey and focused examination of the abdomen. Hypotension should be assumed to result from hemorrhage from an abdominal injury until proven otherwise. Physical examination of the abdomen may be limited by distracting injuries or depressed mental status, but should focus on the elicitation of peritoneal signs, localized tenderness, external bruising or evidence of a “seat-belt sign,” and distension.4 Peritonitis should never be attributed to a solid organ injury, as isolated hemoperitoneum should not cause diffuse peritoneal irritation. Focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) is now commonly performed as part of the initial evaluation. While a “positive” FAST exam reliably identifies the presence of free fluid in the abdominal cavity suggestive of injury, a negative study does not exclude significant abdominal injury and should not be considered a definitive evaluation. Although ultrasound has been used to identify and grade specific organ injuries (i.e., liver and spleen), its reliability and reproducibility in this capacity has not been well demonstrated. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) has largely been replaced by the FAST exam and CT scan and is rarely indicated, although it may be useful in select cases where there is suspicion for hollow viscus perforation with a compromised physical examination and equivocal CT scan findings. However, a diagnostic peritoneal aspirate (DPA) looking for the presence of gross blood only, can be very useful in the patient who is hypotensive with a negative FAST exam. A urinalysis should be obtained on all patients, and evaluation of the complete urinary tract (kidneys, ureters, bladder) should be performed in the presence of significant hematuria.

Computed tomography has become the standard of care for the definitive diagnosis of most blunt abdominal injuries, and should be used liberally. Missed intra-abdominal injuries, typically resulting from an incomplete diagnostic evaluation, represent the most common cause of preventable deaths from trauma.5 Modern generation helical CT scanners provide excellent detailed imaging of the abdominal organs, including retroperitoneal structures and major vasculature. It has a sensitivity and specificity approaching 100% for solid organ injuries, and provides anatomic detail that is invaluable for injury grading.1,3 The abdominal CT scan should always be performed using intravenous contrast if possible, as a “contrast blush” can provide evidence of active bleeding or arteriovenous fistula. Although some older series have characterized CT as unreliable for hollow viscus perforation or duodenal/pancreatic injury, more recent experience demonstrates that a high-quality CT scan will correctly identify most of these injuries. However, repeat CT imaging (if no other indication for laparotomy is present) or DPL should be considered in those infrequent situations with a high index of suspicion for missed injury or equivocal findings on the initial CT scan. We perform the abdominal CT scan with intravenous contrast only, as oral contrast has been shown to add little value in the trauma setting and may create undue delay as well as risk aspiration. Oral contrast may be useful when obtaining a delayed CT scan to evaluate for hollow viscus perforation, or to better delineate known or suspected pancreatic or duodenal injuries.

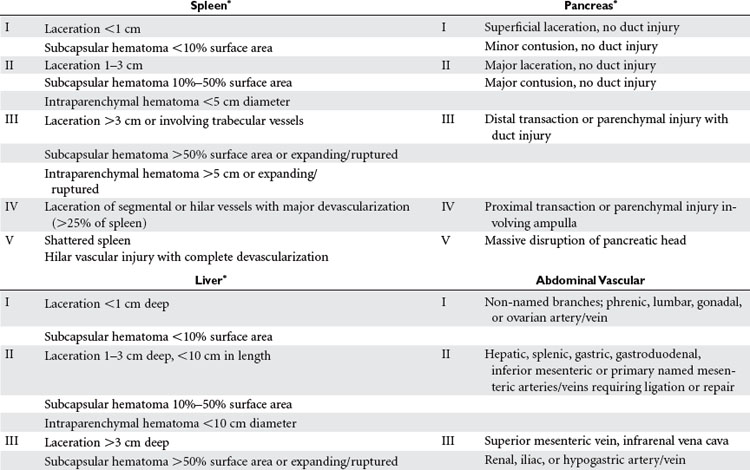

Anatomic Location of Injury and AAST-OIS Grading

Abdominal injuries identified by CT should be graded according to the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma–Organ Injury Scale (AAST-OIS system) (Table 1). This provides a commonly understood language for discussion and study of these injuries, and may be used to guide the level and duration of monitoring for nonoperative management. Although higher-grade injuries are associated with higher rates of morbidity and failure of nonoperative management, the grade of injury should not be the primary factor in this decision. All grades of injury may be successfully managed nonoperatively in the appropriate clinical setting. Additional factors such as the amount of hemoperitoneum, presence of associated injuries, and presence of a contrast “blush” should be noted and factored into subsequent management decisions.

Management

Initial management decisions in patients with a known or suspected intra-abdominal injury should be based on the clinical examination and hemodynamic status. Patients with peritonitis or hemodynamic instability that persists despite adequate fluid resuscitation should undergo prompt exploratory celiotomy. Fluid resuscitation in the early evaluation period should be administered judiciously and only if necessary. Overzealous volume resuscitation with elevation of the mean arterial pressure may exacerbate hemorrhage from the injured organ or may cause an iatrogenic drop in the hemoglobin by hemodilution, which may be difficult to differentiate from active bleeding. We prefer small-volume boluses with immediate assessment of the patient’s response by an experienced trauma surgeon. There is a mounting body of evidence that supports the positive resuscitation and immunomodulatory benefits of hypertonic crystalloid solutions over standard crystalloid or colloid formulas.6 Administration of small boluses of hypertonic fluid (100 cc–250 cc of 3%–7.5% saline) will result in decreased tissue edema with improved gas exchange, a decreased systemic and organ-specific inflammatory response, with an excellent safety profile. In patients with associated traumatic head injury, hypertonic saline has the added benefit of lowering intracranial pressure while volume resuscitating the patient.

The primary components of safely managing these injuries are appropriate monitoring and frequent reassessments of the patient’s clinical exam and laboratory values. The level of inpatient care (intensive care unit [ICU] versus ward) and the frequency of monitoring should be dictated by the patient’s clinical status, associated injuries, and the severity of the organ injury. All personnel caring for the patient should be made aware of the presence and type of abdominal injury, and a clear plan for monitoring and alerting the trauma team to any changes should be in place. Most injuries that fail nonoperative management will declare themselves within 48 hours of injury, and this should be the period of most intensive monitoring.

Additional important factors to be considered in guiding management are the age of the patient and the presence of comorbidities and associated injuries. Traditionally, nonoperative management of abdominal solid organ injuries was contraindicated in elderly patients and those with multiple associated injuries, particularly severe traumatic brain injuries. However, with improvements in imaging technology and monitoring capabilities, many centers are reporting favorable results of nonoperative management in these more difficult patient populations.7,8 Success rates for nonoperative management of over 90% have been reported among patients with multiple associated injuries, with similar complication rates to those with isolated injuries.9,10 This should only be attempted at centers with experience and expertise in managing complex, multisystem trauma and requires coordination and cooperation between the involved surgical services, such as neurosurgery and orthopedics.

Spleen and Liver

Patients with any identified injury of the spleen and/or liver should be admitted to the hospital for a minimum of 24–48 hours of observation. We recommend ICU or intermediate-level (step-down) admission for all high-grade injuries (grades III through V) (Figures 1 and 2). The primary purpose of observation is to identify the presence of any associated abdominal injuries and to monitor for ongoing or recurrent bleeding from the liver or spleen. The overall incidence of missed injuries in these patients appears to be low (around 2%), and should not influence the decision for nonoperative management.5,11 Serial physical examinations should focus on the patient’s hemodynamic status and any evidence of worsening abdominal tenderness, distension, or the development of peritonitis. Serial laboratory evaluations should include a complete blood count at the minimum. Some measure of global tissue perfusion and acidosis, such as the lactate or base deficit, may be useful in making management and treatment decisions in these patients. The timing and appropriateness of blood transfusion in these patients remains an area of controversy. Although the need for transfusion was previously used as a guideline for operative intervention, this is no longer the case. For spleen injuries, we favor a low threshold for operative or angiographic intervention if the patient requires more than one to two units of transfused blood. We accept a higher threshold for surgical intervention on liver injuries that require transfusion, typically after four to six units of transfused blood. Ideally it would be preferred if one could avoid transfusion and surgery, but the exact timing of transfusion, surgery, or both for patients with solid organ injuries remains more an art than science. It requires the expert judgment of an experienced trauma surgeon to avoid the error of delaying a needed laparotomy until the patient is on the verge of hemodynamic collapse.

Kidney

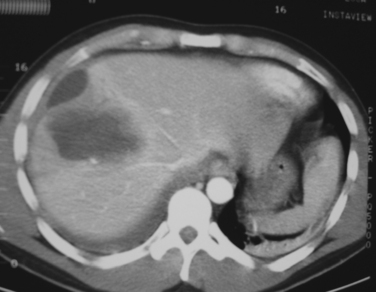

The kidneys are highly amenable to nonoperative management of most blunt injuries, with successful nonoperative management reported in over 90% of injuries and even in up to 50% of grade V injuries.12,13 This is particularly important for preserving renal function, as a significant number of surgical explorations for blunt renal injury will result in nephrectomy. Tamponade of hemorrhage from the renal parenchyma is enhanced by the tough, fibrous capsule of the kidneys (Gerota’s fascia) and their retroperitoneal location. The principles of hospital admission, monitoring, and serial evaluations are the same as for liver and spleen injuries. In addition to serial hemoglobin assessments for bleeding, measures of renal function (blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, creatinine clearance) should be obtained at admission and intermittently throughout the hospital stay. A urinary catheter should be placed to quantify urine output and the degree of hematuria (if present) in the initial observation period. We recommend liberal use of repeat imaging, including renal function studies, in patients with grades III through V injuries to assess the extent of injury and amount of functional renal parenchyma remaining (Figure 3).

Duodenum and Pancreas

Injury to the duodenum or pancreas is rare after blunt trauma, and appears to occur more frequently in children compared with adults. Diagnosis of these injuries is difficult because of their retroperitoneal location, often subtle clinical signs, and frequent poor visualization by CT scan. Unlike other abdominal organ injuries, most identified duodenal and pancreatic injuries will require operative exploration for repair and drainage. However, select lower-grade injuries may be amenable to successful nonoperative management. Most grade I injuries of the duodenum (hematoma or partial-thickness laceration) do not require laparotomy and will resolve spontaneously. Patients with a large intramural hematoma, particularly children, may experience obstructive symptoms and require hospitalization for nutritional management until the hematoma shrinks and obstruction resolves. Repeat imaging with oral contrast may be helpful in these patients to assess the degree of luminal obstruction and resolution or progression of the lesion.

Role of Angiographic Interventions

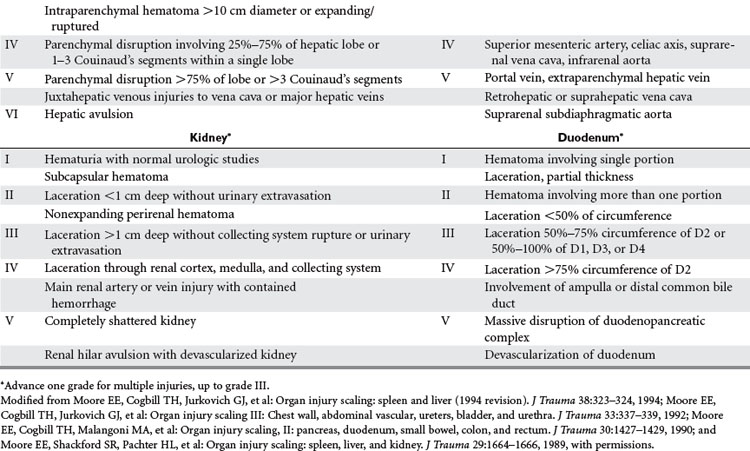

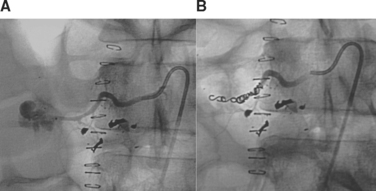

The increased abilities and availability of interventional radiology are now being widely applied to the management of traumatic abdominal injuries, and may offer significant benefit in the nonoperative management of select injury types.14 The most common application of these techniques in the abdomen is to control active hemorrhage from the spleen or liver by angioembolization of either the bleeding vessel (selective) or the proximal main vessel supplying the bleeding area (nonselective). Patients with a contrast blush seen on the initial CT scan or evidence of ongoing hemorrhage should be considered for angiographic embolization if they remain hemodynamically stable enough to undergo the procedure. Although there are no well-defined criteria for prophylactic embolization, we recommend it in the nonoperative management of complex hepatic injuries (grades IV and V) that have a high rate of recurrent bleeding and failure of nonoperative management. Angiographic embolization is currently performed with either coil placement, which causes permanent clotting of the vessel, or with absorbable Gelfoam. Gelfoam usually only provides temporary occlusion of the vessel, and as recanalization can occur in 8–96 hours, the patient should be monitored for recurrent hemorrhage.

Morbidity and Complications Management

The amount and degree of morbidity associated with nonoperative management of blunt abdominal injuries will be a function of the specific organ injured, the presence and degree of associated injuries, and patient factors such as age and comorbid disease. Avoiding a laparotomy does not equate to avoiding any morbidities, and in some cases may be associated with equal or greater morbidity than operative management. Although hemorrhage from a missed solid organ injury has classically been described as the most common cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in trauma patients, this should be an extremely rare occurrence in a modern, dedicated trauma center. Approximately 25% of patients with abdominal organ injuries managed nonoperatively will develop a complication requiring some form of intervention, and over 80% of these can be successfully managed without surgical intervention.2,9,11

The key to optimizing patient outcomes after blunt abdominal injury is anticipation of the commonly associated complications, and institution of a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and management. Any change in the patient’s clinical status or complaints suggestive of an abdominal complication (pain, fever, emesis, ileus, bleeding, jaundice) should prompt immediate investigation. CT is the study of choice for diagnosing most of these organ-specific complications, and can readily visualize organ necrosis or ischemia, fluid collections (abscess, biloma, urinoma, pseudocyst), biliary ductal dilation, and progression or resolution of the primary organ injury.15 The addition of intravenous contrast can delineate most vascular complications, such as pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous (or portovenous) fistula, intimal dissection, and thrombosis. Arteriography should be performed if the diagnosis is unclear by CT or to perform interventional therapy. Fluoroscopic contrast studies such as intravenous pyelography and retrograde urethrography may be indicated to evaluate the urinary tract for injury or urine leak. Suspected biliary or pancreatic pathology (leaks, fistulae) should be further studied using ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC).

The management of these complications will depend on the nature of the complication, the patient’s clinical status, and the availability of resources and expertise. However, most of these complications may also be managed nonoperatively or with minimally invasive techniques. Although there is no role for prophylactic antibiotics in the nonoperative management of abdominal injuries, appropriate antibiotics should be started immediately when infection is diagnosed or strongly suspected. Percutaneous drainage of abdominal fluid collections can be performed using CT or ultrasound guidance and the fluid should be sent for gram staining and appropriate microbiologic cultures. Additional studies such as bilirubin, creatinine, and amylase levels may assist the diagnosis in cases of suspected biloma, urinoma, or pancreatic leak, and can be followed serially to assess for resolution. Major hepatic injuries with persistent biliary leak should undergo ERCP or PTC with biliary stent placement. Stenting across the ampulla may also decrease or resolve pancreatic ductal leaks. Similarly, persistent urinary extravasation can usually be treated successfully with percutaneous drainage and ureteral stent placement. Repeat imaging studies should be obtained to assess the efficacy of these interventions and the timing of drain or stent removal.

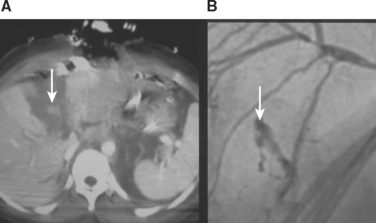

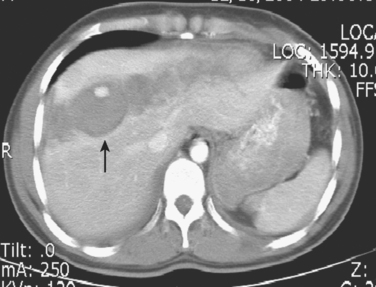

Parenchymal injury to any abdominal organ will result in some degree of tissue necrosis, which is usually followed by tissue regeneration, remodeling, or scar formation. A large volume of necrotic tissue or necrotic tissue that becomes secondarily infected may result in local and systemic complications. This may be particularly pronounced in patients who have decreased organ perfusion after angioembolization. Most patients can be managed successfully with intravenous fluids and antibiotics, and percutaneous drainage should be considered if there is a significant component of liquefied necrosis. However, select patients will require laparotomy with surgical debridement of all necrotic and infected tissue (Figure 4). Finally, vascular complications after blunt abdominal trauma may manifest at any time after the injury, with many being identified years later. Small, asymptomatic pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae may be managed by observation and repeat imaging. Any significant or symptomatic lesion is best managed by angiographic embolization (Figure 5). Hemobilia should be suspected in any patient with evidence of upper GI bleeding after a blunt hepatic injury, and is also best managed by angiographic embolization.

Mortality

The mortality rates for nonoperative management of abdominal injuries will vary widely by the patient population being studied, the specific organ or organs involved, and the grade of organ injury. Death in these patients will most commonly be a result of associated injuries and comorbid conditions, and not directly attributable to the abdominal organ injury. Over half of all deaths in this patient population are attributable to other associated injuries, most commonly closed head and thoracic injuries, with only about 10% of deaths related to hemorrhage from the injured organ.2,9 The overall mortality rate for nonoperative splenic injuries in modern series is approximately 6%, with the mortality doubling for patients older than 55 years.8,11 Failure of nonoperative management is also associated with increased mortality rates of 12%–30%. Nonoperatively managed liver injuries are associated with higher rates of nonoperative failure, continued hemorrhage, and associated injuries, and thus a higher overall mortality compared with splenic injuries. There is an approximate 12% mortality rate for all liver injuries managed nonoperatively, with increased death rates of up to 80% reported for high-grade liver injuries (IV and V).5,12 Failure of nonoperative management, continued organ-related hemorrhage, and overall mortality among these patients doubles when additional abdominal organ injury (spleen, kidney) is present. Similar mortality rates have been reported for renal and other blunt abdominal injuries managed nonoperatively, but again are mainly a function of patient factors and associated injury patterns.13

PENETRATING ABDOMINAL INJURY

There are few situations in the field of surgery that generate as much excitement and adrenaline as a “crash celiotomy” in the trauma patient with a penetrating abdominal injury. Despite the omnipresence of these scenarios in movies and television programs, the overall incidence of penetrating trauma in both the civilian and military setting has sharply declined over recent decades. This has resulted in a paucity of experience with penetrating abdominal injuries among surgeons and residents in all but a few select, high-volume urban centers. In contrast to the revolutions seen in blunt trauma management, there has been relatively little change in the general approach to most penetrating injuries over the past 50 years. While penetrating abdominal trauma with suspicion or evidence of peritoneal violation has traditionally mandated an exploratory celiotomy, there is a small but growing body of experience with selective nonoperative management of civilian penetrating abdominal injuries. While this approach has been well described and is becoming more widely accepted for stab wounds, the selective nonoperative approach to abdominal gunshot wounds remains an area of active study and controversy.

Incidence

The most important issue when discussing the validity of selective nonoperative management of penetrating abdominal wounds is the incidence and type of intra-abdominal organ injury. Approximately half of all patients with anterior abdominal stab wounds and up to 30% of patients with proven peritoneal violation will not have any significant intra-abdominal injury.16,17 The incidence of intraabdominal and retroperitoneal injury is significantly lower for flank or back stab wounds.18 Although there is an alleged greater than 90% incidence of organ injury requiring laparotomy after abdominal gunshot wounds, this mainly applies to high-velocity injuries often seen in military combat, which will not be specifically addressed in this chapter. Approximately 30%–40% of patients with anterior abdominal gunshot wounds and up to 70% with posterior wounds do not have clinically significant intra-abdominal injuries that require surgical therapy.19 Successful selective nonoperative management offers the benefit of avoiding the morbidity of an unnecessary celiotomy, but must always be weighed against the risk of missed or delayed treatment of a significant intra-abdominal injury. Approximately 20%–40% of abdominal gunshot wounds and more than 50% of stab wounds can be successfully and safely managed without celiotomy.

Mechanism of Injury

Tissue and organ injury from penetrating wounds may occur by a variety of mechanisms, and will vary significantly by the type of weapon involved. Stab wounds are very low velocity and produce injury through primary tissue disruption or devascularization at the point of contact. The degree of tissue injury and clinical significance will largely depend on the exact location and depth of the wound. They produce relatively uniform injuries (punctures, lacerations) with little or no damage to surrounding tissue. Although the vast majority of stabbing injuries are direct and linear with forceful insertion and extraction of the blade, one must be aware that on occasion, there can be a pivoting and twisting motion during the injury. The point of pivot is at the skin and this “jug” maneuver can cause seemingly minor injury at the skin but can have a larger lacerating injury within the abdomen (Figure 6).

Despite the long published experience with civilian and military gunshot injuries, there are many misconceptions regarding wound ballistics that have become widely propagated. Although highvelocity types of weapons do impart greater force to the involved tissue, the amount of tissue injury and cavitation will depend more on the properties of the missile (jacketing, deformities, amount of spin and yaw) than the velocity. As an example, a high-velocity jacketed round may pass cleanly through a tissue bed producing little injury, while a low-velocity unjacketed round, which easily deforms and fragments, may produce a significantly larger wound and greater tissue destruction. In addition, the size and clinical significance of the “temporary cavity” has been largely overstated, and appears to be much less than the oft-quoted 20 or 30 times the bullet diameter (Figure 7).20 The dictum that all high-velocity wounds require extensive debridement of the temporary cavity area is not supported by animal or clinical data, and the corollary that all low-velocity wounds require little debridement is equally unsupported.

Diagnosis

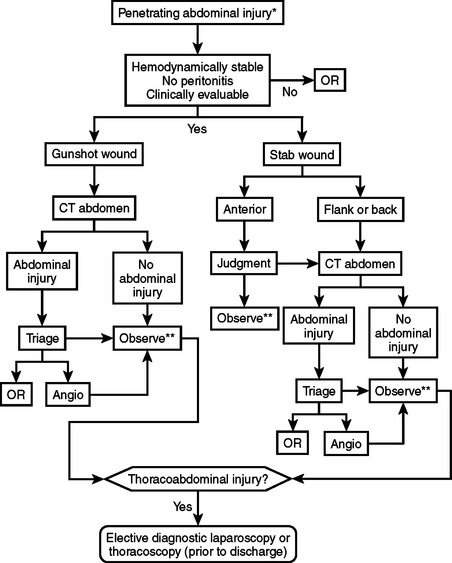

The diagnostic approach to the hemodynamically normal patient with a penetrating abdominal wound is controversial, and will vary by the injury mechanism, wound location, and the patient’s clinical status. The diagnostic paradigm has rightly shifted away from determining whether the peritoneum has been violated, to determining whether there has been an injury that needs surgical therapy. The evaluation should focus on rapidly identifying those patients with injuries requiring immediate or urgent laparotomy, such as hollow viscus perforation or ongoing hemorrhage, and evaluation for significant extra-abdominal injuries.

The diagnostic evaluation of abdominal gunshot wounds has traditionally been minimal, with the diagnosis of most injuries occurring in the operating room during exploratory celiotomy. In the emergency department, a thorough external survey should be performed to identify and mark the location of all wounds, and a radiologic survey (chest, abdomen, and pelvis x-ray) can rapidly identify the number and location of retained missiles or fragments. Despite the oft-repeated entreaty to never probe a penetrating wound, we will liberally (and gently) probe penetrating abdominal wounds to clarify the direction of the tract. This is often useful in determining whether the course of the missile is superficial or if it tracks into the abdominal cavity. Patients who are hemodynamically stable, awake and alert, have a reliable physical exam (no intoxication or significant distracting injuries), and have no other indication for operation or general anesthesia are candidates for nonoperative management. These patients should then undergo an urgent CT scan of the abdomen, which we perform with fine cuts through the area of injury or wound tract. In addition to delineating solid organ and other injuries, the CT scan can be used to reconstruct the missile tract and determine the likelihood of injury to surrounding structures. Close monitoring by an experienced surgeon during the entire radiological evaluation is important to identify any change in clinical status that will mandate urgent operative intervention.19

Upper abdominal stab wounds should have a chest x-ray performed, and any evidence of thoracic involvement (pneumothorax, hemothorax) should be considered diagnostic of a diaphragm injury. Flank or back stab wounds should undergo contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis unless they are clearly superficial in nature. Although some of the literature does recommend triple-contrast CT (IV, oral, rectal), there are other studies that refute the necessity of oral and rectal contrast.18 We have not found that triple-contrast CT is required and prefer to use only intravenous enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis. The role of CT scan for anterior abdominal stab wounds is not well-defined, but should be considered if there is a high suspicion for solid organ injury based on wound location, a positive FAST exam, or hematuria. However, most patients who are hemodynamically stable, have an intact mental status and clear sensorium, and have no evidence of peritonitis do not require any further imaging studies. Although local wound exploration is used by some groups, we do not recommend this strategy as the decision point for celiotomy should be based on the patient’s clinical status and not on evidence of fascial penetration alone.

Anatomic Location of Injury and AAST-OIS Grading

The anatomic location of injury will depend primarily on the wounding mechanism and the tract of injury. Stab wounds will most often be anatomically limited to one area or zone of the abdomen and usually involve only one organ or structure. Gunshot wounds may involve multiple areas of the abdomen, and frequently cross into separate body cavities (thoracic, pelvis) and may also be transaxial (across the midline). Injuries or tracts that involve the upper abdomen or lower chest, defined as the area from the inferior border of the costal margin to the nipple line circumferentially, should be assumed to have penetrated the diaphragm until proven otherwise.21 Organ injuries should be assessed and scored according to the AAST-OIS scheme in the same manner as previously described for blunt abdominal trauma (see Table 1). Although anatomic delineation of the missile tract by CT scan should not be the primary determinant of therapy, it may increase or lower the threshold for performing an exploratory celiotomy.

Management

The most important factors in safe and successful selective nonoperative management for penetrating abdominal injuries are proper patient selection and supervision by an experienced surgeon.19,22 Once the diagnostic evaluation has been completed as outlined above, the patient should be admitted to an area where close observation and monitoring can be easily accomplished for at least 24 hours. Serial laboratory evaluations and examinations should be performed as outlined in the section on blunt abdominal injuries. It is preferable that the serial physical examinations are performed by the same physician (attending or supervised resident) so that subtle changes can be more easily appreciated. Immediate celiotomy is performed at the first indicator of clinical deterioration or development of peritoneal signs. Other factors that should prompt consideration for celiotomy are persistent tachycardia, fever, and rising white blood cell count or worsening metabolic acidosis (base deficit or lactate). Although surgeons are classically taught that the physical examination is unreliable and can miss injuries, we have found that the physical exam is accurate and reliable in determining who requires surgical therapy.

Pain medication may be administered but should be given judiciously and the patient immediately re-evaluated in the presence of increasing abdominal pain. Clear liquids may be administered shortly after admission and prolonged periods of fasting in anticipation of a possible celiotomy should be avoided. There appears to be no benefit (and significant detriment) to prolonged immobility, so early ambulation is encouraged. The duration of intensive monitoring will vary by the type of abdominal injury and associated conditions, but any significant problems such as bleeding or the development of peritonitis will almost always occur within 24–48 hours of injury. Criteria for hospital discharge and instructions should be the same as previously described for blunt organ injuries. Outpatient follow-up and arrangements for emergency care if needed must be ensured before hospital discharge.

The role of angiography and other minimally invasive techniques in penetrating abdominal injuries has not been well studied. The indications and utility of interventional techniques such as angioembolization in the management of hemorrhage from solid organ injuries should be essentially the same as previously described for blunt injuries (Figures 8 and 9). In addition, angiography and embolization should be considered for all high-grade liver injuries (grades IV and V) or if angiography is already being performed for other reasons.22 Even after the successful nonoperative management of a penetrating injury, laparoscopic or thoracoscopic evaluation of the diaphragm may be required for select high-risk injury locations (as outlined in the previous section).21 However, this should be considered an elective procedure and should not be done until the patient has been observed for long enough to ensure clinical stability and no other indication for celiotomy develops.

Morbidity and Complications Management

The most significant concern among this patient cohort is the incidence and outcome of failures of nonoperative management. Although there is an overall high incidence of injuries requiring celiotomy with penetrating abdominal wounds, there is an extremely low incidence of these injuries among the cohort of patients who qualify for selective nonoperative management as previously described. For both abdominal stab and gunshot wounds, approximately 4% of patients initially managed nonoperatively go on to require celiotomy, most commonly for the development of peritoneal signs. The morbidity and mortality rates associated with delayed celiotomy are low, and are comparable to those undergoing immediate celiotomy. However, there is a significant benefit of selective nonoperative management in reducing the incidence of nontherapeutic laparotomies from 30%–50% down to 5%–10%.19 This will translate into a significant reduction in resource utilization, patient morbidity, and costs to the hospital and health-care system.

The development of infectious and organ-specific complications and their management among patients managed nonoperatively are essentially the same as previously described for blunt injuries, and will not be repeated here. The role of routine repeat imaging to identify important but clinically silent complications after penetrating solid-organ injuries has not been well defined, and is at the discretion of the managing physician. Delayed imaging (7–10 days postinjury) after severe solid organ injury will identify organ-related complications in up to 50% of patients, with half of these being among asymptomatic patients. Until further data is available on the natural history of these injuries, we recommend liberal use of routine repeat imaging with abdominal CT, which we perform before hospital discharge and at several months postinjury. The majority of identified complications such as fluid collections or vascular pathologies (pseudoaneurysms, arteriovenous fistulae) can be managed nonoperatively, using interventional or minimally invasive adjuncts (see Figure 9). Although the movement toward nonoperative management may be disappointing to surgeons, in most cases it will be beneficial in improving patient outcomes.

Mortality

In the 2005 National Trauma Data Bank™ report, the overall case-fatality rate for gunshot wounds was 16%, and for stab wounds was significantly lower at 1.88%. Mortality will mainly be a reflection of the severity of injuries, patient factors (age, comorbid conditions), and the appropriate postinjury management. Several large series of abdominal stab wounds have reported no deaths among patients initially selected for nonoperative management, even including those who failed and required celiotomy.16,17 Similarly, the reported mortality rates for nonoperative management of abdominal gunshot wounds is less than 1%, and is significantly lower than the 10%–20% mortality among patients managed surgically.19,22 The most important factors for avoiding any preventable mortality from selective nonoperative management are proper patient selection and adherence to strict criteria for monitoring and conversion to operative management.

Although death resulting from a missed intra-abdominal injury has been a primary concern among skeptics of nonoperative management, the collective experience to date confirms that properly performed selective nonoperative management is safe and effective. In fact, it appears that the overall morbidity and resultant mortality rates will be significantly lowered by avoiding the high rates of nontherapeutic celiotomy associated with a policy of liberal celiotomy for penetrating injury.

1 Hoff WS, Holevar M, Nagy KK, et al. Practice management guidelines for the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 2002;53(3):602-615.

2 Knudson MM, Maull KI. Nonoperative management of solid organ injuries: past, present, and future. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79(6):1357-1371.

3 Alonso M, Brathwaite C, Garcia V, et al. Practice management guidelines for the nonoperative management of blunt injury to the liver and spleen. Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, 2003. http://www.east.org/tpg/livspleen.pdf

4 Poletti PA, Mirvis SE, Shanmuganathan K, et al. Blunt abdominal trauma patients: can organ injury be excluded without performing computed tomography? J Trauma. 2004;57(5):1072-1081.

5 Miller PR, Croce MA, Bee TK, et al. Associated injuries in blunt solid organ trauma: implications for missed injury in nonoperative management. J Trauma. 2002;53(2):238-244.

6 Kramer GC. Hypertonic resuscitation: physiologic mechanisms and recommendations for trauma care. J Trauma. 2003;54(5 Suppl):S89-S99.

7 Cocanour CS, Moore FA, Ware DN, et al. Age should not be a consideration for nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury. J Trauma. 2000;48(4):606-612.

8 Harbrecht BG, Peitzman AB, Rivera L, et al. Contribution of age and gender to outcome of blunt splenic injury in adults: multicenter study of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 2001;51(5):887-895.

9 Malhotra AK, Latifi R, Fabian TC, et al. Multiplicity of solid organ injury: influence on management and outcomes after blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 2003;54(5):925-929.

10 Nix JA, Costanza M, Daley BJ, et al. Outcome of the current management of splenic injuries. Trauma. 2001;50(5):835-842.

11 Haan JM, Bochicchio GV, Kramer N, et al. Nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury: a 5-year experience. J Trauma. 2005;58(3):492-498.

12 Sartorelli KH, Frumiento C, Rogers FB, et al. Nonoperative management of hepatic, splenic, and renal injuries in adults with multiple injuries. J Trauma. 2000;49(1):56-62.

13 Toutouzas KG, Karaiskakis M, Kaminski A, et al. Nonoperative management of blunt renal trauma: a prospective study. Am Surg. 2002;68(12):1097-1103.

14 Carrillo EH, Spain DA, Wohtlmann CD, et al. Interventional techniques are useful adjuncts in the nonoperative management of hepatic injuries. J Trauma. 1999;46(4):619-624.

15 Demetriades D, Karaiskakis M, Alo K, et al. Role of postoperative computed tomography in patients with severe liver injury. Br J Surg. 2003;90(11):1398-1400.

16 Robin AP, Andrews JR, Lange DA, et al. Selective management of anterior abdominal stab wounds. J Trauma. 1989;29(12):1684-1689.

17 Demetriades D, Rabinowitz B. Indications for operation in abdominal stab wounds. A prospective study of 651 patients. Ann Surg. 1987;205(2):129-132.

18 Hauser CJ, Huprich JE, Bosco P, et al. Triple-contrast computed tomography in the evaluation of penetrating posterior abdominal injuries. Arch Surg. 1987;122(10):1112-1115.

19 Velmahos GC, Demetriades D, Toutouzas KG, et al. Selective nonoperative management in 1,856 patients with abdominal gunshot wounds: should routine laparotomy still be the standard of care? Ann Surg. 2001;234(3):395-403.

20 Fackler ML. Civilian gunshot wounds and ballistics: dispelling the myths. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1998;16(1):17-28.

21 Murray JA, Demetriades D, Asensio JA, et al. Occult injuries to the diaphragm: prospective evaluation of laparoscopy in penetrating injuries to the left lower chest. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187(6):626-630.

22 Demetriades D, Gomez H, Chahwan S, et al. Gunshot injuries to the liver: the role of selective nonoperative management. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188(4):343-348.