CHAPTER 7 Nonoperative Management and Rehabilitation of the Hip

Introduction

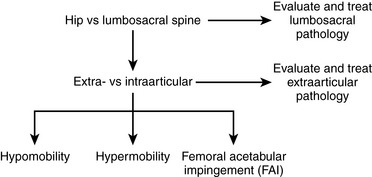

Evaluation algorithms and classification-based treatment systems are commonly used in the orthopedic community to assist with determining a diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention plan. An algorithm implemented during the patient evaluation allows for the systematic collection of information, whereas classification-based treatment defines subgroups of patients who are likely to respond to a specific treatment approach. A number of evaluation algorithms and classification-based treatment systems have been developed for various body regions; however, there are few that are specific to the hip. We have integrated an evaluation algorithm and classification-based treatment to help conservatively manage individuals with hip pain; this plan includes the consideration of the lumbosacral spine, the extra-articular soft tissue, and the intra-articular structures. Intra-articular pathologies are further divided to consider the issues of impingement, hypermobility, and hypomobility. An outline of our proposed algorithm can be found in Figure 7-1.

Lumbosacral spine

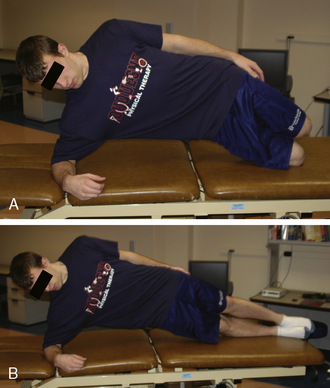

Examination and treatment with the mobilization of the lumbosacral complex are supported in the literature for individuals with hip pain. Cibulka and Delitto found that athletes with anterior or lateral hip pain and positive signs of sacroiliac joint dysfunction have a favorable treatment outcome with mobilization directed at the sacroiliac joint. The technique we use as an intervention for patients who we feel meet the criteria for the mobilization subgroup is depicted in Figure 7-2. The technique involves positioning the patient in a side-bending position toward and with rotation away from the painful side, with respect to the lumbar spine. A force directed anterior to posterior is applied to the ipsilateral anterior superior iliac spine with a Grade 5 thrusting maneuver. It should be noted that, before this manipulation is applied, contraindications for a thrust mobilization must be thoroughly cleared. The effect of this technique for reducing the patient’s hip pain is assessed. Depending on the amount of pain reduction and the results of reassessing previously positive signs, the evaluation can continue accordingly. In general, patients who fall into this category are also given lumbopelvic range-of-motion and stabilizing exercises. We find that patients with hip pain commonly have signs and symptoms that are consistent with this category and that they often positively respond to some degree to this mobilization technique.

Extra-articular soft-tissue disorders

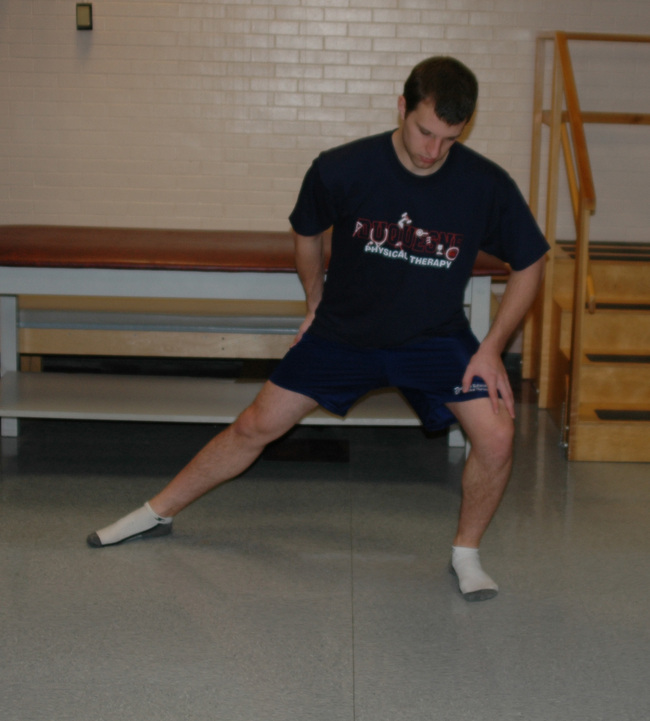

The treatment of trochanteric bursitis with proximal ITB syndrome can involve a generic progression of therapy: decrease inflammation, improve the range of motion, increase strength, and return to activity. Proper ITB stretching is done with adduction, slight extension, and slight external rotation, as outlined in Figure 7-3. We also find benefit from the manual stretching depicted in Figure 7-4. It makes sense to incorporate components of both hip flexion and hip extension into the adduction stretch because of the attachments of both the tensor and gluteus maximus to the ITB. Other manual stretching, deep soft-tissue mobilization and massage, and other modalities may be indicated. We find that the most successful treatments include interventions that address more than the lateral hip pain and that also correct any biomechanical abnormalities and muscle imbalances.

Intra-articular pathology

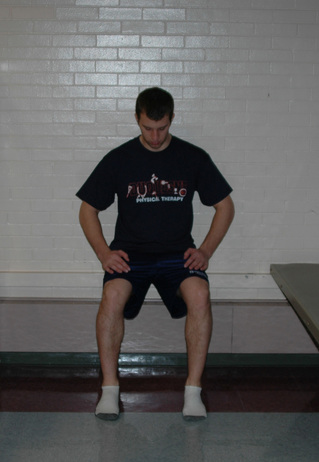

Capsular laxity of the hip may be comparable with capsular laxity of the shoulder. Generally, individuals with this condition have engaged in repetitive forceful rotational activities. We commonly find that repeated forceful external rotation to the end of the range of motion causes iliofemoral ligament insufficiency. The logroll test typically demonstrates an increase in motion on the involved side as compared with the uninvolved side in these individuals. Treatment generally emphasizes strengthening the surrounding musculature and performing neuromuscular training and proprioceptive exercises. Patients with anterior hip laxity commonly elicit symptoms of instability with external rotation of the hip (e.g., when swinging a golf club). Exercises that reproduce these movements are avoided, whereas closed-chain activities with internal rotation are encouraged. We commonly use an exercise that incorporates the use of a resistive rubber cord, as depicted in Figure 7-5. During this exercise, it is important to maintain a neutral and stable pelvis to work the internal rotators and to engage the gluteus medius and the lumbopelvic stabilizers.

The most compelling evidence for the treatment of hypomobility resulting from arthritic changes relates to the use of manual hip mobilization. We use a distraction technique that positions the hip in an open-pack position (30 degrees of flexion, 30 degrees of abduction, and 5 degrees of external rotation) while a traction force is applied, as shown in Figure 7-6. Increases in joint motion may be achieved by instituting a progressive series of joint mobilization techniques followed by stretching, as tolerated. We have found that improvements in motion allow the patient to perform daily activities at a higher level with less pain.

Specific exercises

Hip Musculature

During rehabilitation, the muscles that surround the hip joint are commonly targeted for strengthening. These muscles include the gluteus maximus, the gluteus medius, the internal rotators, and the external rotators. We commonly use weight-bearing hip internal rotation (see Figure 7-5), weight-bearing hip abduction (Figure 7-7), resisted lateral walking, mini squats with resisted abduction and external rotation, and step-up exercises, as appropriate, in our strengthening program. There are a number of studies that have demonstrated the potential effectiveness of various exercises to strengthen the muscles that surround the hip joint. Bolgla and colleagues found that weight-bearing left hip abduction with the hip at 0 degrees and 20 degrees of flexion demonstrated significantly more right gluteus medius electromyographic activity as compared with similar non–weight-bearing exercises. Ayotte and colleagues demonstrated that unilateral wall squat, forward step-up, retro step-up, lateral step-up, and unilateral mini squat exercises all produced electromyographic activity within a strengthening range. The unilateral wall squat and the forward step-up produced significantly greater activity than the other three exercises. As the individual completes exercises that focus on the hip musculature, we emphasize trunk stabilization to engage the lumbopelvic stabilizers. We also modify or omit any exercise that aggravates patient symptoms.

Lumbopelvic Musculature

Similar to scapulothoracic stabilization for patients with shoulder pathology, we feel that lumbopelvic stabilization exercises may need to be given to those patients with musculoskeletal conditions of the hip. We commonly use exercises to target the lumbar extensors, the abdominal musculature, and the quadratus laborum. These exercises include posterior pelvic tilting, bridging with resisted hip abduction and external rotation, quadruped alternating hip and shoulder lift (Figure 7-8), side plank progressions (Figure 7-9), and prone plank (Figure 7-10). Again, we modify or omit any exercise that aggravates patient symptoms.

Conclusion

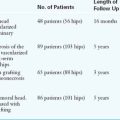

This chapter outlines the evaluation process that we use to develop an intervention plan to conservatively manage individuals with musculoskeletal-related hip pathology. We have integrated a general evaluation algorithm and classification-based treatment that includes considerations of the lumbosacral spine, the extra-articular soft tissue, and the intra-articular structures. Intra-articular pathologies are further divided to consider the issues of impingement, hypermobility, and hypomobility. Table 7-1 presents a summary of the interventions that we commonly use to treat the various conditions outlined in this chapter. In addition, the CD that accompanies this book contains a user-friendly version of this table that will allow health care professionals to produce exercise programs; these programs contain pictures and instructions that can be given to patients in a clinical setting.

Table 7–1 An Overview of Interventions for Common Musculoskeletal Hip Disorders

| Diagnosis | Intervention Techniques |

|---|---|

| Femoral acetabular impingement |

Specific exercises that can be used for patient home programs are included in the Expert Consult website.

Table 7–1 An Overview of Interventions for Common Musculoskeletal Hip Disorders

| Diagnosis | Intervention Techniques | |

|---|---|---|

| Femoral acetabular impingement | Link to Exercises | |

| Hypermobility |

• Closed-chain strengthening for hip musculature in the frontal and transverse (internal rotation) planes

|

Link to Exercises |

| Hypomobility: cartilage/degenerative changes | Link to Exercises | |

|

• Acute injuries: modalities to promote healing and decrease pain and inflammation, such as massage, submaximal isometric exercises, passive range-of-motion exercises, and lumbopelvic stabilizing exercises

|

||

| Trochanteric bursitis/iliotibial band syndrome | Link to Exercises |

Specific exercises that can be used for patient home programs are included in the Expert Consult website.

Illustrations for Exercises

Abdominal Stretch Lie on your stomach. Straighten your arms so that you are bending at the waist to feel stretching in your abdominal area.

Hip Adductor Stretch As shown in the diagram, stand with your___leg slightly behind you and rotated outward. Lean to the___so that stretching is felt in your___groin.

Standing ITB Stretch While standing, cross your___leg behind your opposite leg and side bend to the___so that a stretch is felt in outer part of your___hip. Reach to the___to intensify the stretch.

Isometric Hamstrings Lie on your back with your___knee bent to approximately___degrees. Contract your hamstring by digging your heel into the table.

Isometric Adduction Lie on your back with a pillow between your knees. Squeeze your legs together into the pillow.

Lateral Step Downs Stand with your___foot on a step. Bend your___knee so that you slowly lower body___inches. During the movement make sure your hips remain straight.

Side lying Hip Abduction Lie on your___side and slowly raise your___leg approximately___inches while keeping your leg straight. Return to the start position.

Standing Hip Adduction with Theraband®Resistance As shown in the diagram, tie Theraband® to your___leg. Kick your___leg across your body while keeping your knee straight. During the movement make sure to keep your hips straight.

Standing Hip Extension with Theraband® Resistance As shown in the diagram, tie Theraband® to your___leg. Kick your___leg backwards while keeping your knee straight. During the movement make sure to keep your hips straight.

Standing Hip Abduction with Theraband®Resistance As shown in the diagram, tie Theraband® to your___leg. Kick your___leg out to the side while keeping your knee straight. During the movement make sure to keep your hips straight.

Annotated references and suggested readings

Altman R., Alarcon G., Appelrouth D., et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum.. 1991;34:505-514.

Ayotte N.W., Stetts D.M., Keenan G., Greenway E.H. Electromyographical analysis of selected lower extremity muscles during 5 unilateral weight-bearing exercises. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther.. 2007;37:48-55.

Bolgla L.A., Uhl T.L. Electromyographic analysis of hip rehabilitation exercises in a group of healthy subjects. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther.. 2005;35:487-494.

Brown M.D., Gomez-Marin O., Brookfield K.F., Li P.S. Differential diagnosis of hip disease versus spine disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 2004;419:280-284.

Childs J.D., Fritz J.M., Piva S.R., Erhard R.E. Clinical decision making in the identification of patients likely to benefit from spinal manipulation: a traditional versus an evidence-based approach. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther.. 2003;33:259-272.

Cibulka M.T., Delitto A. A comparison of two different methods to treat hip pain in runners. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther.. 1993;17:172-176.

Delitto A., Erhard R.E., Bowling R.W. A treatment-based classification approach to low back syndrome: identifying and staging patients for conservative treatment. Phys Ther.. 1995;75:470-485. discussion 485–489

Fritz J.M., Cleland J.A., Childs J.D. Subgrouping patients with low back pain: evolution of a classification approach to physical therapy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther.. 2007;37:290-302.

Hicks G.E., Fritz J.M., Delitto A., McGill S.M. Preliminary development of a clinical prediction rule for determining which patients with low back pain will respond to a stabilization exercise program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.. 2005;86:1753-1762.

Hinman R.S., Heywood S.E., Day A.R. Aquatic physical therapy for hip and knee osteoarthritis: results of a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther.. 2007;87:32-43.

Hoeksma H.L., Dekker J., Ronday H.K., et al. Comparison of manual therapy and exercise therapy in osteoarthritis of the hip: a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum.. 2004;51:722-729.

Holmich P., Uhrskou P., Ulnits L., et al. Effectiveness of active physical training as treatment for long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes: randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:439-443.

Messier S.P., Gutekunst D.J., Davis C., DeVita P. Weight loss reduces knee-joint loads in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum.. 2005;52:2026-2032.

Nicholas S.J., Tyler T.F. Adductor muscle strains in sport. Sports Med.. 2002;32:339-344.

This review article describes treatment guidelines for adductor muscle strains..

Tyler T.F., Nicholas S.J., Campbell R.J., McHugh M.P. The association of hip strength and flexibility with the incidence of adductor muscle strains in professional ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med.. 2001;29:124-128.

Whitman J.M., Flynn T.W., Childs J.D., et al. A comparison between two physical therapy treatment programs for patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2006;31:2541-2549.

Youdas J.W., Kotajarvi B.J., Padgett D.J., Kaufman K.R. Partial weight-bearing gait using conventional assistive devices. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.. 2005;86:394-398.