Nonfunctioning pituitary tumors

1. Name the functioning pituitary tumors.

The normal pituitary gland secretes prolactin, growth hormone (GH), corticotropin (ACTH), thyrotropin (TSH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinizing hormone (LH). The major functioning pituitary tumors are prolactin-secreting tumors, GH-secreting tumors, ACTH-secreting tumors, TSH-secreting tumors, and gonadotropin (FSH- and/or LH-)- secreting tumors. Some tumors secrete a mixture of hormones. These are all covered in other chapters.

2. What is a nonfunctioning pituitary tumor?

A nonfunctioning pituitary tumor arises from pituitary cells but does not secrete clinically detectable amounts of a pituitary hormone. These tumors are usually benign adenomas.

The alpha subunit is a component of three pituitary glycoprotein hormones: TSH, FSH, and LH. Each of these hormones consists of the common alpha subunit and a specific beta subunit (TSH beta, FSH beta, and LH beta). The alpha and beta subunits combine and become glycosylated before the intact hormone is secreted. Some nonfunctioning pituitary tumors secrete measurable amounts of the free alpha subunit, which may therefore serve as a tumor marker.

4. What other lesions can resemble nonfunctioning pituitary tumors?

Tumors that are not of pituitary origin may be found within the sella turcica; examples are metastatic carcinomas, craniopharyngiomas, meningiomas, and neural tumors. Nonneoplastic Rathke’s pouch cysts, arterial aneurysms, and infiltrative pituitary diseases, such as sarcoidosis, histiocytosis, tuberculosis, lymphocytic hypophysitis, and hemochromatosis, may also be seen.

5. Differentiate between a microadenoma and a macroadenoma.

A pituitary microadenoma is less than 10 mm in its largest dimension, whereas a macroadenoma is 10 mm or larger. A macroadenoma may be contained entirely within the sella turcica or may have extrasellar extension.

6. Which structures may be damaged by growth of a pituitary tumor outside the sella turcica?

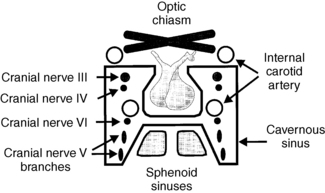

Pituitary tumors that grow superiorly may compress the optic chiasm and pituitary stalk. Those that grow laterally can invade the cavernous sinuses and compress cranial nerves III, IV, and VI or the internal carotid artery. Inferior growth may erode into the sphenoid sinus. Anterior and posterior growth often erodes the bones of the tuberculum sellae and dorsum sellae, respectively (Fig. 19-1).

Figure 19-1. Pituitary fossa.

7. What are the clinical features of nonfunctioning pituitary tumors?

Nonfunctioning pituitary tumors are often asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally during cranial imaging procedures performed for other reasons. This is true of both microadenomas and macroadenomas. Tumors that cause symptoms are usually large, space-occupying macroadenomas, which compress nearby neurologic or vascular structures (see Fig. 19-1). Clinical features include headaches, visual field defects, visual loss, and extraocular nerve palsies. Pituitary insufficiency also may result from destruction of normal pituitary tissue.

8. What anatomic evaluation is necessary for a pituitary tumor?

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) of the pituitary gland and parasellar regions often allows a precise diagnosis and determines the presence and extent of extrasellar invasion. Visual field testing helps assess function of the optic chiasm and tracts. Angiography may be necessary in some cases to rule out an aneurysm.

9. What evaluation is necessary to determine that a pituitary tumor is nonfunctioning?

A thorough history and physical examination can detect symptoms and/or signs of pituitary hormone excess. Hormone testing should include measurement of serum prolactin, GH, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), TSH, free thyroxine (free T4), LH, FSH, testosterone (men), estradiol (women), and 24-hour urinary cortisol excretion. Measurement of the serum alpha subunit is also helpful.

10. Does an elevated serum prolactin value indicate that a tumor is functioning?

No. Secretion of prolactin is negatively regulated by hypothalamic inhibitory factors, such as dopamine, which reach the anterior pituitary gland through the pituitary stalk. Stalk compression from a nonfunctioning tumor can impair dopamine delivery and thus increase the release of prolactin from the normal pituitary gland. The serum prolactin rarely exceeds 100 ng/mL in such cases, whereas it is usually much higher with prolactin-secreting tumors.

11. What is the natural history of nonfunctioning pituitary tumors?

Macroadenomas are three to four times more likely than microadenomas to exhibit progressive growth. Solid tumors grow much more often than cystic lesions. People with macroadenomas are more likely to demonstrate hypopituitarism, compressive symptoms, and pituitary apoplexy, although the latter occurrence is still quite rare.

12. What is the primary treatment for a nonfunctioning pituitary tumor?

A microadenoma can be managed with observation by serial imaging studies. Surgical removal should be considered for a macroadenoma; however, serial observation is an option if the tumor is not growing or causing compressive symptoms.

The treatment of choice for symptomatic tumors is transsphenoidal pituitary surgery. Primary radiation therapy may be used if surgery is contraindicated or not desired. Medications, such as dopamine agonists (bromocriptine, cabergoline) and somatostatin analogs (octreotide, lanreotide) are rarely helpful in the treatment of nonfunctioning pituitary tumors.

13. Is postoperative radiation therapy recommended for incompletely resected tumors?

Radiation therapy is not necessary in all cases of incomplete surgical resection. It is advised when the tumor remnants are large, compressive, or growing. Stereotactic radiotherapy is generally preferred over conventional radiation therapy because it delivers a greater focused radiation dose to neoplastic tissue with less radiation exposure to surrounding structures. Residual disease of lesser severity may be monitored with imaging studies and not treated unless growth occurs.

14. What endocrine complications occur in the immediate postoperative period?

Transient diabetes insipidus (vasopressin deficiency) manifested as high-volume urine output is common in the first few days. It may be followed by a short period (1-2 days) of water intoxication (vasopressin excess) causing hyponatremia. Both conditions result from removal, trauma, or edema of the neurohypophysis, where vasopressin is stored. Fluid balance and serum electrolytes must therefore be closely monitored. Secondary adrenal insufficiency is of little immediate concern because high-dose dexamethasone is often given postoperatively to prevent cerebral edema, but it may become apparent after dexamethasone is stopped. Deficiencies of other pituitary hormones are not usually early postoperative problems if their levels were normal preoperatively.

15. What is the management of postoperative diabetes insipidus and water intoxication?

Mild postoperative diabetes insipidus can be managed with isovolumetric, isotonic fluid replacement. More severe cases should be treated with desmopressin (DDAVP), 0.25 to 0.5 mL (1-2 μg) two times a day intravenously or subcutaneously or with aqueous vasopressin, 5 units subcutaneously every 4 to 6 hours, until urine volumes become normal. If hyponatremia develops, vasopressin must be reduced or stopped, and free water intake restricted. If diabetes insipidus persists beyond 1 week, patients may be switched to intranasal DDAVP, 0.1 to 0.2 mL once or twice daily, or oral DDAVP tablets, 0.1 to 0.4 mg daily.

16. What endocrine problems may occur during long-term follow-up?

Deficiencies of other pituitary hormones may develop weeks, months, or years later, especially if radiation therapy was given. The only major concern in the first month is adrenal insufficiency. During this time, one should question patients about suggestive symptoms and, if present, measure a morning cortisol level. If the morning cortisol level is low (<10 μg/dL), hydrocortisone replacement should be initiated, and the patient retested in 3 to 6 months with a cosyntropin stimulation test. At that time, levels of serum free thyroxine (T4), TSH, IGF-1, LH, FSH, testosterone (men), and estradiol (women) should also be checked, and replacement therapy considered for any identified deficiencies. It is recommended that these levels then be monitored at 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter.

17. Summarize the long-term management of pituitary insufficiency.

TABLE 19-1.

LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT OF PITUITARY INSUFFICIENCY

| HORMONE DISORDER | MANAGEMENT |

| Adrenal insufficiency | Physiological glucocorticoid replacement |

| Hypothyroidism | Levothyroxine replacement |

| Hypogonadism (men) | Androgen gels, patches, or injections |

| Hypogonadism (women) | Oral or transdermal contraceptives or postmenopausal hormone replacement |

| Growth hormone (GH) | Growth hormone replacement |

| Diabetes insipidus | Desmopressin nasal spray or oral tablets |

18. Describe the clinical features of pituitary carcinomas.

Pituitary carcinomas, which are extremely rare, expand rapidly and have mass effects. Some secrete hormones causing endocrine syndromes similar to those seen with adenomas. Metastatic disease to the central nervous system, cervical lymph nodes, liver, and bone is commonly associated.

19. What is the treatment for pituitary carcinoma?

Transsphenoidal surgery followed by radiation therapy is the treatment of choice. No successful use of chemotherapy has been reported for pituitary carcinoma.

20. What is the prognosis for pituitary carcinoma?

21. Which cancers metastasize to the pituitary gland?

Metastatic disease to the pituitary gland occurs in approximately 3% to 5% of patients with widely disseminated carcinoma. The most commonly reported primary tumors are those of breast, lung, kidney, prostate, liver, pancreas, and nasopharynx, plasmacytoma, sarcoma, and adenocarcinoma of unknown primary site.

Arafah, BM, Kailani, SH, Nekl, KE, et al. Immediate recovery of pituitary function after transsphenoidal resection of pituitary macroadenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:348–354.

Arafah, BM, Prunty, D, Ybarra, J, et al. The dominant role of increased intrasellar pressure in the pathogenesis of hypopituitarism, hyperprolactinemia, and headaches in patients with pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1789–1793.

Barker, FG, Klibanski, A, Swearingen, B, Transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary tumors in the United States, 1996–2000. mortality, morbidity, and effects of hospital and surgeon volume. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:4709–4719.

Branch CL, Jr., Laws ER, Jr. Metastatic tumors of the sella turcica masquerading as primary pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;65:469–474.

Dekkers, GM, Pereira, AM, Romijn, JA. Treatment and follow-up of clinically non-functioning pituitary macroadenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3717–3726.

Dudziak, K, Honegger, J, Bornemann, A, et al. Pituitary carcinoma with malignant growth from first presentation and fulminant clinical course – case report and review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2665–2669.

Famini, P, Maya, MM, Melmed, S, Pituitary magnetic resonance imaging for sellar and parasellar masses. ten-year experience in 2598 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:1633–1641.

Fernandez-Balsells, MM, Murad, MH, Barwise, A, et al, Natural history of nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas and incidentalomas. a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:905–912.

Freda, PU, Beckers, AM, Katznelson, L, et al, Pituitary incidentalomas. an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:894–904.

Hannon, JM, Finucane, FM, Sherlock, M, et al. Disorders of water homeostasis in neurosurgical patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1423–1433.

Kaltsas, GA, Mukherjee, JJ, Plowman, PN, et al. The role of cytotoxic chemotherapy in the management of aggressive and malignant pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:4233–4238.

Loeffler, JS, Shih, HA. Radiation therapy in the management of pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1992–2003.

Mukherjee, JJ, Islam, N, Kaltsas, G, et al, Clinical, radiological and pathological features of patients with Rathke’s cleft cysts. tumors that may recur. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:2357–2362.

Pernicone, PJ, Scheithauer, BW, Sebo, TJ, et al, Pituitary carcinoma. a clinicopathological study of 15 cases. Cancer 1997;79:804–812.

Ramirez, C, Cheng, S, Vargas, G, et al, Expression of Ki-67, FGFFR4, and SSTR 2, 3, and 5 in nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas. a high throughput TMA, immunohistochemical study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:1745–1751.

Shin, JL, Asa, SL, Woodhouse, LJ, et al, Cystic lesions of the pituitary. clinicopathological features distinguishing craniopharyngioma, Rathke’s cleft cyst, and arachnoid cyst. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:3972–3982.

Swords, FM, Allan, CA, Plowman, PN, Stereotactic radiosurgery XVI. a treatment for previously irradiated pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:5334–5340.

Wilson, CB, Extensive personal experience. surgical management of pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:2381–2385.