Chapter 17

Non–ST Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome

1. What is non–ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome?

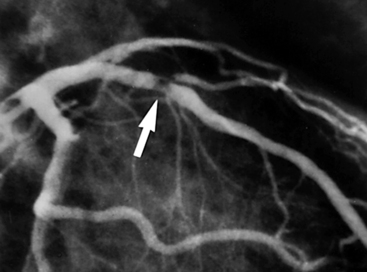

It is now recognized that unstable angina, non–Q wave myocardial infarction (MI), non–ST segment elevation MI, and ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are all part of a continuum of the pathophysiologic process in which a coronary plaque ruptures, thrombus formation occurs, and partial or complete, transient or more sustained vessel occlusion may occur (Fig. 17-1). This process is deemed acute coronary syndrome when it is clinically recognized and causes symptoms. Acute coronary syndromes can be subdivided for treatment purposes into non–ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) and ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (STE-ACS).

Figure 17-1 Plaque rupture in the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery has led to thrombus formation (arrow) and partial occlusion of the vessel. (Reproduced with permission from Cannon CP, Braunwald E: Unstable angina and non–ST elevation myocardial infarction. In Libby P, Bonow R, Mann D, et al, editors: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders, p. 1179)

2. What is the current definition of a myocardial infarction?

Electrocardiogram (ECG) changes indicative of new ischemia (new ST-T changes or new left bundle branch block)

Electrocardiogram (ECG) changes indicative of new ischemia (new ST-T changes or new left bundle branch block)

Development of pathologic Q waves in the ECG

Development of pathologic Q waves in the ECG

Imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormalities

Imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormalities

3. What other conditions besides epicardial coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndrome can cause elevations in troponin?

Although troponins have extremely high myocardial tissue specificity and sensitivity with new assay, numerous conditions besides epicardial coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes may cause elevations of troponins. Such conditions include noncoronary cardiac disease (myocarditis, acute congestive heart failure [CHF] exacerbation, cardiac contusion, apical ballooning syndrome), acute vascular pathology (hypertensive crisis, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolus), infiltrative diseases (amyloidosis, sarcoidosis), and systemic illnesses (anemia, chromic kidney disease [CKD], hypothyroidism, hypoxemia). Conditions that have been associated with elevation of troponin levels are given in Table 17-1.

TABLE 17-1

CONDITIONS OTHER THAN CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE ASSOCIATED WITH ELEVATION IN CARDIAC TROPONIN

| System | Causes of Troponin Elevation |

| Cardiovascular | Acute aortic dissection Arrhythmia Medical ICU patients Hypotension Heart failure Apical ballooning syndrome Cardiac inflammation Endocarditis, myocarditis, pericarditis Hypertension Infiltrative disease Amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis, scleroderma Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Myocardial injury | Blunt chest trauma Cardiac surgeries Cardiac procedures Ablation, cardioversion, percutaneous intervention Chemotherapy Hypersensitivity drug reactions Envenomation |

| Respiratory | Acute PE ARDS |

| Infectious/Immune | Sepsis/SIRS Viral illness Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| Gastrointestinal | Severe GI bleeding |

| Nervous system | Acute stroke Ischemic stroke Hemorrhagic stroke Head trauma |

| Renal | Chronic kidney disease |

| Endocrine | Diabetes Hypothyroidism |

| Musculoskeletal | Rhabdomyolysis |

| Integumentary | Extensive skin burns |

| Inherited | Neurofibromatosis Duchenne muscular dystrophy Klippel-Feil syndrome |

| Others | Endurance exercise Environmental exposure Carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide |

Reproduced with permission from Januzzi JL Jr: Causes of Non-ACS Related Troponin Elevations. Available at http://www.cardiosource.org. Accessed February 16, 2013.

4. What are the factors that make up the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Risk Score?

Three or more risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD)

Three or more risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD)

Prior catheterization demonstrating CAD

Prior catheterization demonstrating CAD

Two or more anginal events within 24 hours

Two or more anginal events within 24 hours

5. What are the components of the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) ACS Risk Model (at the time of admission)?

The components of the GRACE ACS Risk Model at the time of admission consist of:

Scores are calculated based on established criteria. Calculation algorithms are easily downloadable to computers and handheld devices. A low-risk score is considered 108 or less and is associated with a less than 1% risk of in-hospital death. An intermediate score is 109 to 140 and is associated with a 1% to 3% risk of in-hospital death. A high-risk score is greater than 140 and associated with a more than 3% risk of in-hospital death.

6. What other biomarkers and measured blood levels have been shown to correlate with increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcome?

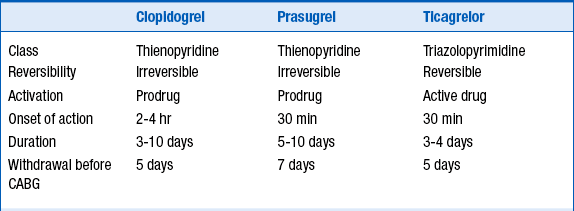

7. What are the differences between the oral antiplatelet agents?

More recently, the thienopyridine prasugrel and the triazolopyrimidine ticagrelor have been approved for use. These two agents have been studied in patients with ACS undergoing stent implantation. Like clopidogrel, both are P2Y12 blockers. Both these newer agents are more potent than clopidogrel, leading to greater and more reliable platelet inhibition than clopidogrel. They also both have a shorter onset of action than clopidogrel. Like clopidogrel, prasugrel irreversibly inhibits the platelet. Although ticagrelor does not irreversibly inhibit the platelet, there nevertheless is effective platelet inhibition for days following discontinuation of ticagrelor. The characteristics of these 3 agents are summarized in Table 17-2.

TABLE 17-2

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE THREE ORAL P2Y12 INHIBITOR ANTIPLATELET AGENTS USED IN THE TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH NSTE-ACS

NSTE-ACS, Non–ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome.

Reproduced with permission from Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al: ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 32:2999-3054, 2011.

8. What antiplatelet agents are recommended in the ACCF/AHA and ESC guidelines?

The ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend administration of either clopidogrel, ticagrelor, or a glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa inhibitor (in addition to aspirin) in patients who are to be treated with an early invasive strategy. Administration of both an oral P2Y12 inhibitor and an intravenous antiplatelet agent can be considered in certain circumstances in which a patient with high risk characteristics is to be treated with an early invasive strategy. Prasugrel can be considered as the P2Y12 agent in patients who are undergoing PCI with coronary stent implantation. The ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend clopidogrel or ticagrelor (in addition to aspirin) in patients to be treated with an initial conservative strategy.

The antiplatelet recommendations of the ACCF/AHA and the ESC NSTE-ACS guidelines are summarized in Table 17-3.

TABLE 17-3

ACCF/AHA AND ESC GUIDELINES FOR ANTIPLATELET THERAPIES IN PATIENTS WITH NSTE-ACS

ACCF/AHA Guidelines

Class I

Clopidogrel, ticagrelor or prasugrel should be administered at least 12 months in patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention.

Clopidogrel, ticagrelor or prasugrel should be administered at least 12 months in patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention.

Class IIa

It is reasonable to omit GP IIb/IIIa if early invasive strategy and patient treated with bivalirudin and with clopidogrel (>6 hr).

It is reasonable to omit GP IIb/IIIa if early invasive strategy and patient treated with bivalirudin and with clopidogrel (>6 hr).

For initial conservative strategy, if already on ASA and clopidogrel (or ticagrelor) and has recurrent ischemia, add GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors.

For initial conservative strategy, if already on ASA and clopidogrel (or ticagrelor) and has recurrent ischemia, add GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors.

Class IIb

Class III—No benefit

Class III—Harm

ESC Guidelines

Class I

Ticagrelor is recommended for all patients at mod-high ischemic events regardless of initial treatment strategy.

Ticagrelor is recommended for all patients at mod-high ischemic events regardless of initial treatment strategy.

Prasugrel is recommended for P2Y12 inhibitor naive patient with known coronary anatomy and planned for PCI without contraindications.

Prasugrel is recommended for P2Y12 inhibitor naive patient with known coronary anatomy and planned for PCI without contraindications.

GP IIb/IIIa (in addition to dual oral antiplatelet agents) in high-risk patients (elevated troponin, visible thrombus) is recommended if the risk of bleeding is low.

GP IIb/IIIa (in addition to dual oral antiplatelet agents) in high-risk patients (elevated troponin, visible thrombus) is recommended if the risk of bleeding is low.

Class IIa

Eptifibatide and tirofiban added to aspirin should be considered prior to angiography in high-risk patients not preloaded with P2Y12 inhibitors.

Eptifibatide and tirofiban added to aspirin should be considered prior to angiography in high-risk patients not preloaded with P2Y12 inhibitors.

Class IIb

Platelets function analysis or genotyping might be considered in selected cases where result may alter the management.

Platelets function analysis or genotyping might be considered in selected cases where result may alter the management.

Class III

NSAIDs (nonselective or COX-2 inhibitors) should not be administered during UA/NSTEMI, except aspirin.

NSAIDs (nonselective or COX-2 inhibitors) should not be administered during UA/NSTEMI, except aspirin.

Routine GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors with ASA and/or P2Y12 inhibitor is not recommended, particularly in those undergoing medical management without PCI.

Routine GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors with ASA and/or P2Y12 inhibitor is not recommended, particularly in those undergoing medical management without PCI.

Modified from Wright RS; Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al: 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update of the Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (Updating the 2007 Guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 123:2022-2060, 2011; Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, et al: 2012 ACCF/AHA Focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update). J Am Coll Cardiol 2012:645-81; and Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al: ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 32:2999-3054, 2011.

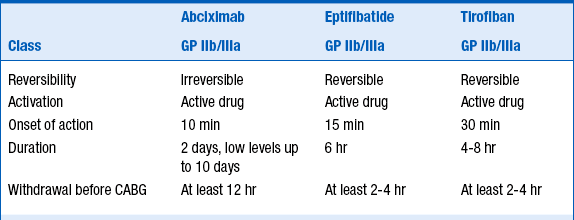

9. What are the differences between the intravenous antiplatelet agents?

Eptifibatide (Integrilin) and tirofiban (Aggrastat) are small-molecule GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors that are used both for “upfront” treatment of NSTE-ACS and during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Abciximab (ReoPro) is an antibody fragment that is used predominantly at the time of PCI (although there is a very specific circumstance in which it can be considered in NSTE-ACS patients before PCI is performed). Eptifibatide and tirofiban lead to reversible platelet inhibition, whereas abciximab leads to irreversible platelet inhibition. All 3 agents lead to a high degree of platelet inhibition, are associated with a small but real increased risk of major bleeding, and are associated with a small (1% to 4%) incidence of thrombocytopenia. Thrombocytopenia can occur rapidly and be profound, and careful monitoring of platelet counts is warranted when these agents are begun. The characteristics of these 3 agents are summarized in Table 17-4.

TABLE 17-4

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE 3 INTRAVENOUS ANTIPLATELET AGENTS USED IN THE TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH NSTE-ACS

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; GP, glycoprotein.

Modified with permission from Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al: ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 32:2999-3054, 2011.

10. What anticoagulant agents are recommended by the ACCF/AHA and ESC guidelines?

The ESC guidelines place a strong emphasis on the prevention of bleeding complications and preferentially recommend fondaparinux, with a single bolus of UFH (85 IU/kg or 60 IU/kg in the case of concomitant use of GP IIb/IIIa) at the time of the PCI. If fondaparinux is not available, enoxaparin (1 mg/kg twice daily) is recommended. If fondaparinux or enoxaparin are not available, UFH with a target aPTT of 50-70 sec (or other low molecular weight heparin) is recommended.

Bivalirudin plus provisional GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors are recommended as an alternative to UFH plus GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, particularly in patients with a high risk of bleeding who are subject to invasive strategy. Anticoagulant agents recommendations are summarized in Table 17-5.

TABLE 17-5

ACCF/AHA AND ESC GUIDELINES FOR ANTITHROMBIN THERAPIES IN PATIENTS WITH NSTE-ACS∗

ACCF/AHA Guidelines

Class I

ESC Guidelines

Class I

If initial anticoagulant is fondaparinux, a single bolus of UFH 85 IU/kg or 60 IU/kg in the case of concomitant use of GP IIb/IIIa should be added at the time of PCI.

If initial anticoagulant is fondaparinux, a single bolus of UFH 85 IU/kg or 60 IU/kg in the case of concomitant use of GP IIb/IIIa should be added at the time of PCI.

If fondaparinux or enoxaparin are not available, UFH with a target PTT of 1.5 to 2.5 times control is indicated.

If fondaparinux or enoxaparin are not available, UFH with a target PTT of 1.5 to 2.5 times control is indicated.

Bivalirudin plus provisional GP IIb/IIIa are recommended as an alternative to UFH plus GP IIb/IIIa particularly in patients with a high risk of bleeding planned for urgent or early invasive strategy.

Bivalirudin plus provisional GP IIb/IIIa are recommended as an alternative to UFH plus GP IIb/IIIa particularly in patients with a high risk of bleeding planned for urgent or early invasive strategy.

Class III

Modified from Wright RS; Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al: 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update of the Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (Updating the 2007 Guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 123:2022-2060, 2011; and Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al: ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 32:2999-3054, 2011.

11. What is the recommended dosing of unfractionated heparin?

ACCF/AHA: 60 U/kg bolus (max. 4000 U), then initial infusion of 12 U/kg (max. initial infusion 1000 U/hr). Target anti-Xa is 0.3 to 0.7; target activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) is 1.5 to 2.5 times control (60 to 80 seconds per ACCP guidelines).

ACCF/AHA: 60 U/kg bolus (max. 4000 U), then initial infusion of 12 U/kg (max. initial infusion 1000 U/hr). Target anti-Xa is 0.3 to 0.7; target activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) is 1.5 to 2.5 times control (60 to 80 seconds per ACCP guidelines).

ESC: 60 to 70 U/kg bolus (max. 5000 U), then initial infusion of 12 to 15 U/kg (initial max. 1000 U/hr). Target aPTT is 50 to 75 seconds (1.5 to 2.5 times control).

ESC: 60 to 70 U/kg bolus (max. 5000 U), then initial infusion of 12 to 15 U/kg (initial max. 1000 U/hr). Target aPTT is 50 to 75 seconds (1.5 to 2.5 times control).

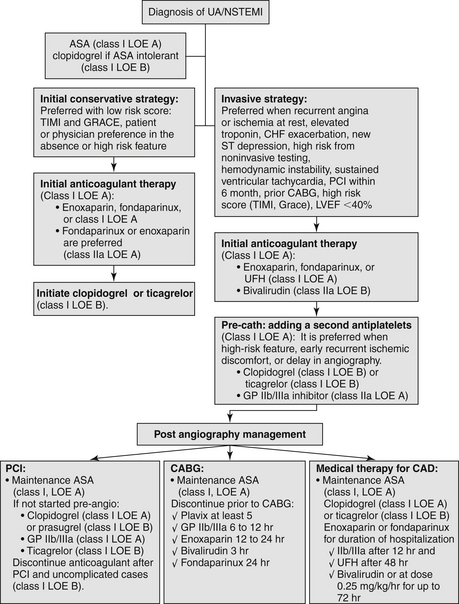

12. Which patients with NSTE-ACS should be treated with a strategy of early catheterization and revascularization?

The ACCF/AHA criteria for elevated risk for clinical events (Fig. 17-2) include recurrent angina/ischemia, elevated troponin, new ST depression, CHF exacerbation, reduced left ventricular (LV) function, high-risk findings on noninvasive testing, hemodynamic instability, sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT), PCI within 6 months, prior coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), and high risk score (TIMI ≥ 6, GRACE > 140).

Figure 17-2 Flowchart management for Class I and Class IIa recommendation for non–ST segment elevation acute cardiac syndrome (NSTE-ACS) by the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association. ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; GP, glycoprotein; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; LOE, level of evidence; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Study Group; UA/NSTEMI, unstable angina/non–ST segment elevation myocardial infarction.

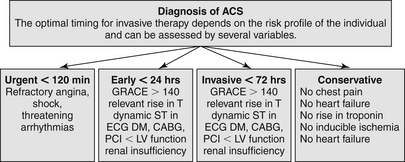

The ESC criteria of high-risk features (Fig. 17-3) include elevated troponin, dynamic ST or T-wave changes, diabetes mellitus (DM), reduced renal function (glomerular filtration rate [GFR] less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), ejection fraction (EF) less than 40%, early post-MI angina, PCI within the past 6 months, prior CABG, and intermediate to high GRACE risk score. Urgent invasive strategy (within 120 minutes after first medical contact) should be for very high-risk patients: refractory angina, recurrent angina despite intense anti-anginal treatment, with ST depression or deep negative T wave, hemodynamic instability (shock), and life-threatening arrhythmias (ventricular fibrillations or ventricular tachycardia).

Figure 17-3 Flowchart management for non–ST segment elevation acute cardiac syndrome (NSTE-ACS) by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). ACS, Acute cardiac syndrome; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG, electrocardiogram; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Hemodynamically unstable patients should generally undergo immediate catheterization.

13. Should platelet function testing be used routinely to determine platelet inhibitory response?

No. Currently the routine use of platelet function test in NSTE-ACS is not recommended by the ACCF/AHA or ESC. However, it may be considered in selected cases if the results of testing may alter management (Class IIb; level of evidence [LOE] B).

14. Should nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or COX-2 inhibitors (other than aspirin) be continued in patients admitted for NSTE-ACS?

15. Can nitrate therapy be administered to patients currently taking erectile dysfunction agents?

Vardenafil (Levitra): not established at the time of this writing, but common sense would dictate at least 24 hours and perhaps a little longer

Vardenafil (Levitra): not established at the time of this writing, but common sense would dictate at least 24 hours and perhaps a little longer

16. Can statin therapy be safely started in patients admitted with acute coronary syndromes?

17. What are the recommendations regarding drug discontinuation in patients who are to undergo CABG?

Wait at least 5 days after the last dose of clopidogrel or ticagrelor before CABG.

Wait at least 5 days after the last dose of clopidogrel or ticagrelor before CABG.

Wait at least 7 days after the last dose of prasugrel before CABG.

Wait at least 7 days after the last dose of prasugrel before CABG.

Discontinue eptifibatide or tirofiban at least 2 to 4 hours before CABG; discontinue abciximab at least 12 hours before CABG.

Discontinue eptifibatide or tirofiban at least 2 to 4 hours before CABG; discontinue abciximab at least 12 hours before CABG.

Discontinue enoxaparin 12 to 24 hours before CABG and dose with UFH.

Discontinue enoxaparin 12 to 24 hours before CABG and dose with UFH.

Discontinue fondaparinux 24 hours before CABG and dose with UFH.

Discontinue fondaparinux 24 hours before CABG and dose with UFH.

Discontinue bivalirudin 3 hours before CABG and dose with UFH.

Discontinue bivalirudin 3 hours before CABG and dose with UFH.

References, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Cannon, C.P., Braunwald, E. Unstable angina and non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction. In: Bonow R., Mann D., Zipes P., eds. Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. ed 9. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012:1178–1209.

2. Center for Outcomes Research, University of Massachusetts Medical School. Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Risk Calculator. Available at http://www.outcomes-umassmed.org/grace/acs_risk/acs_risk_content.html. Accessed March 28, 2013

3. Hamm, C., Bassand, J.P., Agewall, S., et al. Task Force for management acute coronary syndromes in patient presenting without-ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology: ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes of patients presenting without ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2999–3054.

4. Thygesen, K., Alpert, J.S., White, H.D. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116(22):2634–2653.

5. Wright, R.S., Anderson, J.L., Adams, C.D., et al. ACC/AHA 2011 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;123:2022–2060.