CHAPTER 75 Non-hyaluronic acid fillers for facial augmentation

Classification of fillers

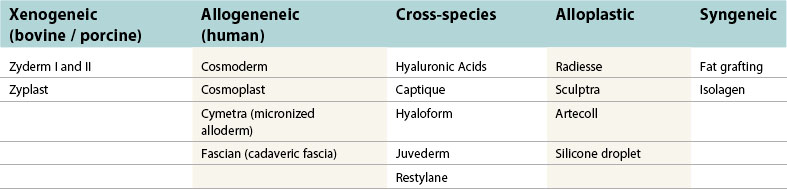

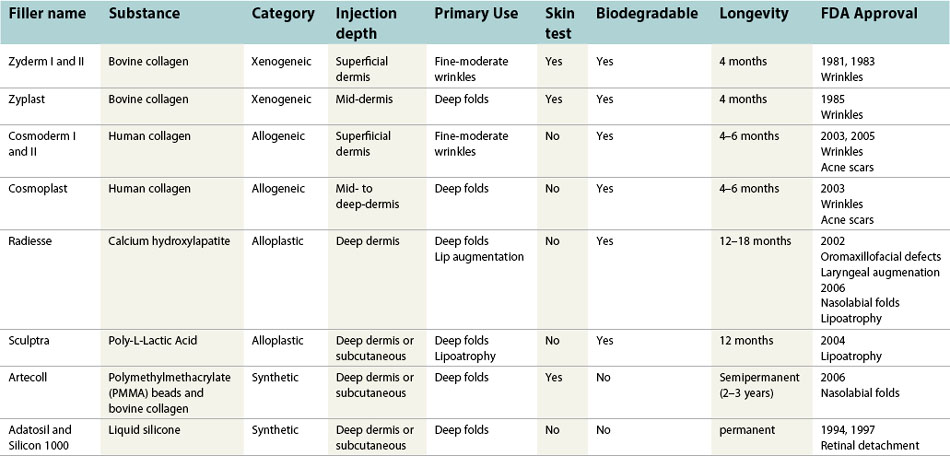

Various types of injectable substances are currently available to restore a youthful appearance. Compounds manufactured from natural tissue may be thought of as biologic, and can be classified based on their origin from either a human (allogeneic) or animal source (xenogeneic). Synthetic, or alloplastic, materials represent man-made compounds used to augment the face for facial rejuvenation. Lastly, autologous tissue that is harvested from elsewhere in the body and used for tissue augmentation may be classified as syngeneic products. An overview of this classification scheme can be found in Table 75.1. The following chapter highlights xenogeneic, allogeneic, and alloplastic soft tissue fillers (Table 75.2).

Physical evaluation

Patient characteristics

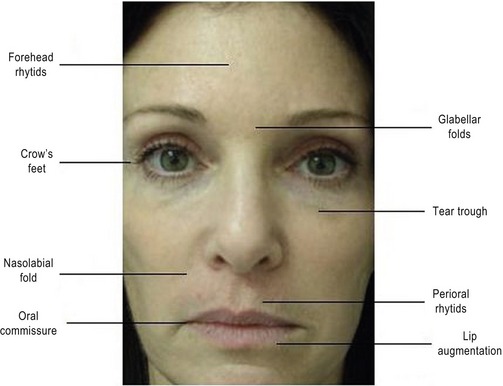

Surgeons should assess the patient’s chief complaints, and determine which anatomic areas soft tissue augmentation may be indicated. Regions of the face that are commonly treated with soft-tissue fillers include forehead wrinkles, glabellar folds, crow’s feet, tear trough, nasolabial fold, perioral rhytids, and lip augmentation (Fig. 75.1).

Technical factors

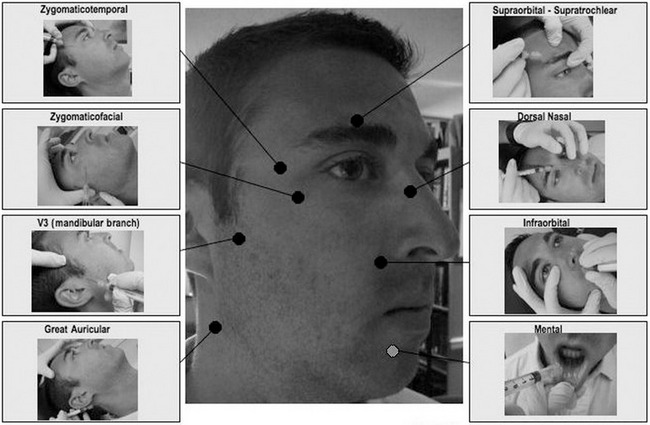

Patient comfort during a filler-procedure is of critical importance. A thorough understanding of the local anesthetic techniques can greatly facilitate patient satisfaction and overall treatment success. Nerve blocks are recommended for injection of soft tissue fillers, and generally can be delivered away from the site of treatment without significantly distorting anatomy. Eight different nerve blocks to anesthetize various regions of the face have been well-described (Fig. 75.2).

Fig. 75.2 Common facial nerve blocks.

Adapted from Zide BM, Swift R. How to block and tackle the face. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;101:840–851.

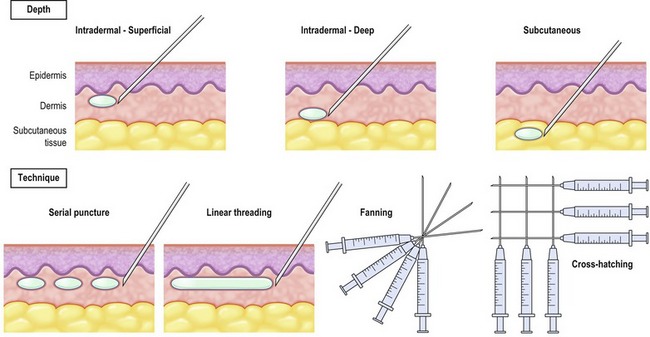

Injection technique is essential to the overall success of soft tissue augmentation with fillers. Important factors to consider with injectable agents include delivery depth (intradermal, subdermal) and technique (serial puncture, threading, fanning, and cross hatching). Physicians should be familiar with the various delivery methods. Serial puncture involves serial injections along a rhytid in order to raise/lift the fold. Serial threading works well for fine wrinkles, as well as glabellar or philtral column enhancement. Linear threading entails insertion of the needle directly to the middle of the wrinkle and delivery of the substance along the whole length of the space. Injection of the filler by linear threading can be done while either advancing or withdrawing the needle. Fanning represents multiple linear injections in a clockwise (or counterclockwise) pattern and is typically applied to deep folds. Cross hatching involves a series of linear injections as a grid, and is advantageous for relatively large treatments areas such as the perioral region (Fig. 75.3).

Technical steps

1. The patient is counseled as to the types of available fillers and which one would be most appropriate for the desired aesthetic result.

2. Risks, benefits, and alternatives of the minimally-invasive procedure are discussed at length including but not limited to those in the section on complications. Risks also may be tailored to emphasize the particular anatomic area involved.

3. Informed consent is obtained.

4. All makeup is removed and treatment areas are wiped with alcohol swabs.

5. While the patient is in an upright position, regions of interest are marked using a delible marking pen. This should be done prior to delivery of anesthetic in order to prevent distortion of the tissue.

6. The patient is placed in a relaxed semi-fowler beach-chair position.

7. Topical anesthetic cream or a facial cooling system can be applied for approximately 15–30 minutes prior to the nerve block or injection

8. An anatomically-specific local nerve block is delivered.

9. The product is injected into the area using the anatomically-appropriate technique: droplet or threading depending on the area and defect.

10. Be mindful of the hydrophilic quality of the product to allow estimation of how much to over- or under-correct.

11. The area is cleansed of all ink marks.

12. The patient is placed in an upright position for a final evaluation.

13. Any small areas necessitating final adjustment are corrected.

14. The physician or assistant performs a final massage and cleans the area while the patient remains seated.

15. Ice is applied to the injected area to minimize echymosis and swelling.

16. Patient is assessed for ambulatory stability.

17. Makeup may then be applied in an adjacent post-procedure area.

Complications

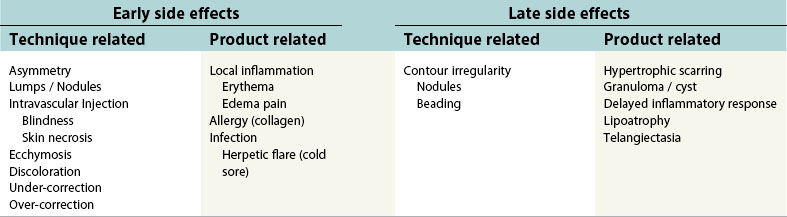

It is imperative that physicians performing injection of soft tissue fillers are aware of potential adverse effects and also discuss them with their patients. Although certain adverse events may be associated with particular fillers, there are a number of side effects that may occur with all types of soft tissue fillers. A summary of early and late side-effects are provided in Table 75.3.

During the early time period following treatment (i.e. 1–7 days), patients may exhibit a localized inflammatory reaction characterized by pain, erythema, and edema. The degree of inflammation one exhibits depends on a number of factors, including the amount of filler delivered, anatomic location, skin quality, and co-morbidities. Herpes simplex virus may be activated in patients undergoing injection of soft tissue fillers. Accordingly, it is recommended that patients with a known history of oral herpes simplex infections be pre-treated with valcyclovir (Valtrex) or acyclovir (Zovirax).

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Ice up the Botox areas, then place the appropriate nerve block for the filler. Use the time that nerve block is taking effect to inject Botox to the desired areas.

• Train with experienced injectors before “experimenting” with the products on your patients.

• “Layering” of products with differing molecular size and cohesiveness may allow a more effective and sometimes longer lasting result.

• Pre- and post-treatment photographs are imperative for comparison, and can often help patients appreciate changes they may otherwise not recognize.

• Use a topical intra-oral cream, (Benzo-gel) before intra-oral V2 and V3 approach.

Pitfalls

• Use a local anesthetic with a vasoconstrictor when working around the periorbital areas to diminish chance of arteriole emboli. Also recommended is compression of the supratrochlear vessels while delivering a filler in order to prevent intravascular injection.

• Always withdraw prior to injection to help prevent embolizing product intra-arterially.

• Thicker fillers (i.e. Zyplast, Cosmoplast) have been associated with vascular compromise and skin sloughing in the glabellar region.

• Injections should be limited to <0.1 mL in order to prevent bumps from forming.

• Inadvertent lumps and bumps that result from injection should be massaged.

Summary of steps

1. The patient is counseled as to the types of available fillers.

2. Risks, benefits and alternatives of procedure are discussed.

3. Informed consent is obtained.

4. Makeup is removed and treatment areas wiped with alcohol swabs.

5. Regions of interest are marked using a delible marking pen.

6. Topical anesthetic cream or a facial cooling system can be applied, and anatomically-specific local nerve block is delivered.

7. The product is injected into the area.

8. The area is cleansed of all ink marks.

9. Any small areas necessitating final adjustment are corrected.

10. Final massage and cleansing.

11. Ice is applied to the injected area.

12. Makeup may then be applied in adjacent post-procedure area.

Born TM, Airan LE, McGrath MH, Hughes CE, Nahai F. Soft tissue fillers in aesthetic facial surgery. The art of aesthetic surgery – principles and techniques. St Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing; 2005.

Broder KW, Cohen SR. An overview of permanent and semipermanent fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3 Suppl):7S–14S.

Fagien S, Klein AW. A brief overview and history of temporary fillers: evolution, advantages, and limitations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(6 Suppl):8S–16S.

Klein AW. Filler materials. Grabb and Smith plastic surgery, 6th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2007.

Lemperle G, Rullan PP, et al. Avoiding and treating dermal filler complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3 Suppl):92S–107S.

Rohrich RJ, Rios JL, et al. Role of new fillers in facial rejuvenation: a cautious outlook. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(7):1899–1902.

Zide BM, Swift R. How to block and tackle the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(3):840–851.