CHAPTER 63 Non-HIV sexually transmitted infections

Introduction

World Health Organization (WHO) estimates suggest that more than 12 million new cases of syphilis, 62 million new cases of gonorrhoea, 92 million new cases of chlamydial infection and 174 million new cases of trichomoniasis occurred throughout the world in 1999 (World Health Organization 2001). Congenital syphilis, prevention of which is relatively easy and cost-effective, may still be responsible for as many as 14% of neonatal deaths. Up to 10% of women who are untreated, or inadequately treated, for chlamydial and gonococcal infections may become infertile as a consequence. On a global scale, up to 4000 newborn babies each year may become blind because of gonococcal and chlamydial ophthalmia neonatorum (note: ophthalmia neonatorum is a notifiable disease).

Epidemiology

WHO estimated that 340 million new cases of STIs occurred worldwide in 1999. The largest number of new infections occurred in South and South-east Asia, followed by sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. However, the highest rate of new cases per 1000 population occurred in sub-Saharan Africa (World Health Organization 2001).

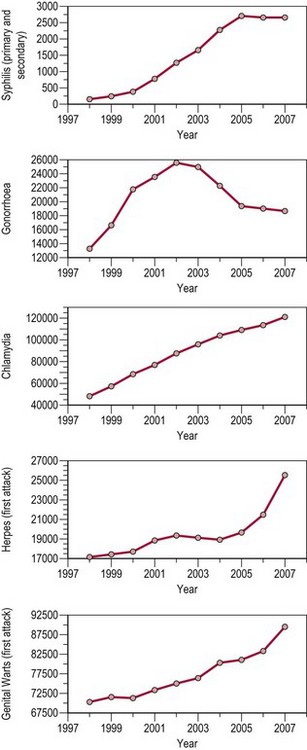

In the UK, peaks in STI diagnoses occurred in the mid-to-late 1940s (post World War II) and from the mid 1960s through to the early 1980s [from the age of sexual liberation to the advent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)]. From 1998 to 2007, there was a substantial increase in diagnoses of most STIs (overall 6%). Cases of uncomplicated gonorrhoea increased by 42%, while chlamydia increased by 150%. Chlamydia has been the most commonly reported STI since 2001, overtaking genital warts (see Figure 63.1).

Figure 63.1 All new episodes of sexually transmitted infections seen in genitourinary medicine clinics 1998–2007.

Source: Health Protection Agency 2008 All new episodes seen at GUM clinics: 1998–2007. United Kingdom and country specific tables.

where Ro is the average number of new infections that result from one infection, β is transmissibility, c is the average rate of acquiring partners, and d is the duration of infection.

Screening

Recommendations 1 and 2: for key groups at risk of STIs

Recommendation 3: patients with an STI

Principles of Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections

History

Whilst in the UK, STIs are principally managed by specialist clinics (GUM), STIs also commonly present to the gynaecologist. The threshold at which the gynaecologist should take a sexual history is correspondingly low. The essentials are establishment of a rapport, privacy and confidence in the manner of questioning. Embarrassment on the part of the patient is quite understandable and should be dealt with empathetically. Phrases can be couched in terms such as ‘I am sorry to have to ask you this, please don’t be offended, it is important’. Essential elements of the sexual history, taken in combination with a general gynaecological and medical history, are shown in Box 63.1.

Specialist clinic tests

In the spirit of the NICE guidelines, time should be allocated to discuss modification of any high-risk activity to prevent reinfection (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2007). This should be non-judgmental and should be accompanied by written information on the subject to reinforce the message.

Genital Herpes

Clinical features

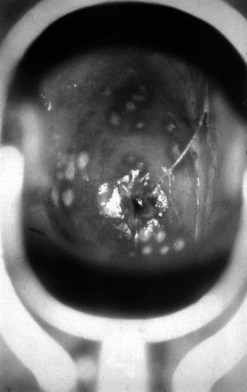

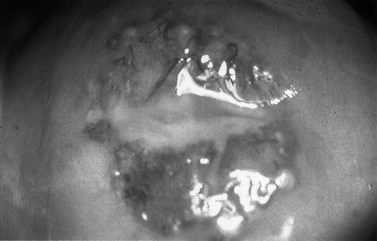

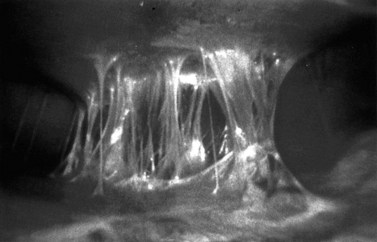

The first episode presents with multiple painful genital ulcers (see Figure 63.2). It is less severe in those with a history of oral herpes. Typical lesions begin as vesicles, at any or all sites from the introitus to the cervix, which become superficial tender ulcers with an erythematous halo and a yellow or grey base (Figure 63.3). Immunocompromised patients may have an atypical appearance which is an elongated ‘knife cut’ ulcer. There may be bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy. Viral shedding continues until the lesions crust over. One-third of patients have systemic symptoms of fever and general malaise. Ten percent will experience viral meningitis with photophobia and headache. A few patients experience retention of urine, either because of pain due to passing urine over the lesions (in which case, micturating in a bath may help) or because of a viral autonomic neuritis. Involvement of other nerves may lead to hyperaesthetic buttocks, thighs or perineum for a time. Severe encephalitis is rare but may be seen more frequently in immunocompromised patients. Without treatment, the first episode lasts for 3–4 weeks.

Diagnosis

Serology

The differential diagnosis of vulval ulcers is shown in Table 63.1.

| Infective | Non-infective |

|---|---|

| Herpes simplex virus | Aphthous ulcers |

| Primary syphilis | Trauma |

| Lymphogranuloma venereum | Skin disease (e.g. lichen sclerosis et atrophicus) Chancroid |

| Donovanosis | Behçet’s syndrome |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | Other multisystem disorder (e.g. sarcoidosis) |

| Dermatitis artefacta |

Treatment

Recurrent genital herpes

General advice includes saline bathing, Vaseline, analgesia and 5% lidocaine (lignocaine) ointment.

Syphilis

Clinical features

Primary syphilis

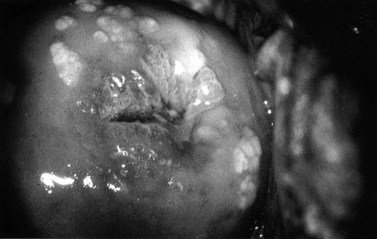

The incubation period after inoculation is 9–90 days (mean 21 days). The lesions may be extragenital and may be multiple. Chancres are usually painless, raised, well-circumscribed ulcers (Figure 63.4). There is a non-tender regional lymphadenopathy. The lesion may well go unnoticed, especially if it is intravaginal or rectal. It will heal spontaneously in 3–10 weeks.

Secondary syphilis

The lesions of secondary syphilis usually manifest some 4–8 weeks after the appearance of the chancre, but sometimes up to 6 months later. In one-third of cases, the chancre is still there. There is a systemic eruption of a non-itchy maculopapular rash, symmetrical and involving the palms and soles (Figure 63.5). Papular lesions may coalesce into large fleshy wart-like lesions, condylomata lata, in areas such as the anus and the labia. Mucous patches and linear (snail-track) ulcers are seen on the mucosae. There may be a generalized lymphadenopathy. The secondary stage involves a bacteraemia with fever, headache, bone pain, alopecia, arthritis and meningitis. There may be hepatitis, optic neuritis and papilloedema. A sensorineural deafness can occur due to destruction of hair cells in the inner ear.

Latent syphilis

Diagnosis

Dark ground microscopy of a wet preparation scraped from the base of a chancre or a lesion of secondary syphilis will display the treponeme as a bluish-white thread-like organism with a coiled body, some 6–20 µm long (Figure 63.6). It is motile and displays three distinct movements: watch-spring, corkscrew and jack-knife. Due to sensitivity and specificity issues with serological testing, this is by far the best chance of establishing a firm diagnosis.

Figure 63.6 Dark ground microscopy showing bluish-white thread-like treponeme.

From Cohen J et al., Infectious Diseases, 3e, with permission of Elsevier.

| Results positive | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| None | Syphilis not present or very early primary syphilis |

| All | Untreated, recently treated or latent syphilis |

| T. pallidum EIA (or FTA) and VDRL | Primary syphilis |

| T. pallidum EIA (or FTA) and TPHA | Treated syphilis or untreated late latent or late syphilis |

| T. pallidum EIA or FTA only | Early primary syphilis, untreated or recently treated early syphilis |

| VDRL/RPR only | False positive reaction |

EIA, enzyme immunoassay; FTA, fluorescent treponemal antibody; VDLR, Venereal Disease Reference Laboratory; TPHA, Treponema pallidum haemagglutination assay; RPR, rapid plasmin reagin.

Management

Box 63.2 shows the guidelines of therapeutic regimens approved by BASHH in 2008 for the treatment of syphilis.

Box 63.2 Guidelines of therapeutic regimens approved by BASHH in 2008 for the treatment of syphilis

Early syphilis (primary, secondary and early latent)

Early syphilis in pregnancy

Lymphogranuloma Venereum

Clinical features

The clinical course of LGV is classically divided into three stages.

Granuloma Inguinale (Donovanosis)

The following is a condensation of the 2001 guidelines for the management of donovanosis (granuloma inguinale) from the Clinical Effectiveness Group (Association for Genitourinary Medicine and the Medical Society for the Study of Venereal Diseases). This can be found on the BASHH website (http://www.bashh.org).

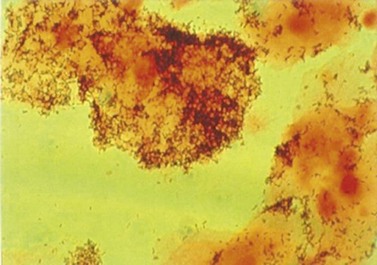

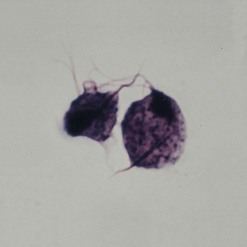

Diagnosis

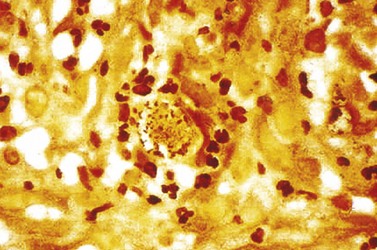

The main method of diagnosis is the demonstration of Donovan bodies (Figure 63.7) in cellular material taken by scraping/impression smear/swab/crushing of pinched off tissue fragments on to a glass slide, or a tissue sample collected by biopsy. Either can be stained by Giemsa.

Gonorrhoea

Clinical features

Diagnosis

Rapid diagnostic tests can be performed to facilitate immediate diagnosis and treatment. Microscopy (×1000) of Gram-stained genital specimens allows direct visualization of N. gonorrhoeae as Gram-negative diplococci within polymorphonuclear leukocytes (Figure 63.9).

Chlamydia

Clinical features

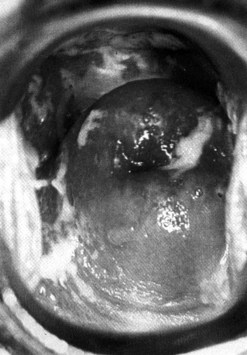

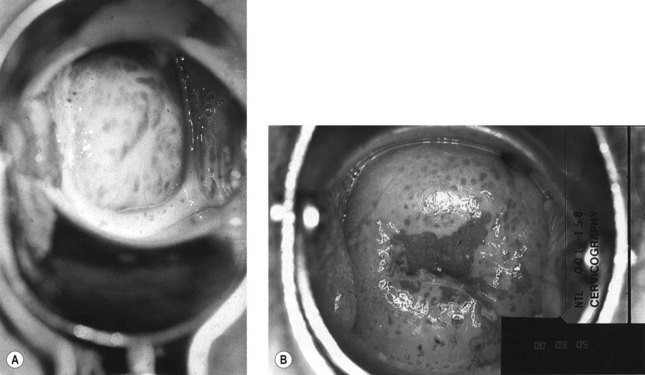

Chlamydia is asymptomatic in approximately 70% of infected women, but may cause any of the following: postcoital or intermenstrual bleeding, lower abdominal pain, purulent vaginal discharge, mucopurulent cervicitis (see Figure 63.10) and/or contact bleeding or dysuria. Rectal infections are usually asymptomatic, but may cause anal discharge and anorectal discomfort (proctitis).

Genital Warts (Condylomata Accuminata)

Diagnosis

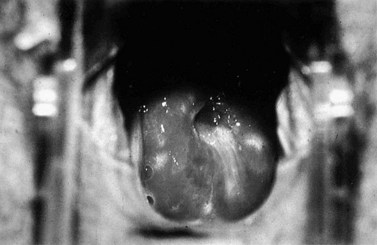

Between 1998 and 2007, the diagnosis of genital warts rose by 28%. The diagnosis is solely on clinical appearance. Warts in women are most commonly found on the vulva, but may appear anywhere in the anogenital area. They are usually painless. The presence of another STI is common (25%), and a full screen should be undertaken (see Figures 63.12 and 63.13).

Molluscum Contagiosum

Aetiology and clinical features

After an incubation period of 3–12 weeks, discrete, pearly, papular, smooth or umbilicated lesions appear (Figure 63.10). In immunocompetent individuals, the size of the lesions seldom exceeds 5 mm, and if untreated, there is usually spontaneous regression after several months. Secondary bacterial infection may result if lesions are scratched. In the immunocompromised, lesions may become large and exuberant, and secondary infection may be problematic. As other STIs may coexist, a full screen for these should be undertaken. HIV testing is recommended in patients presenting with facial lesions.

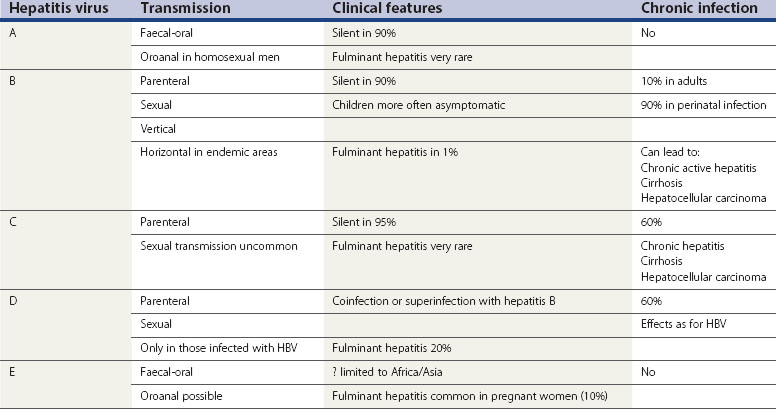

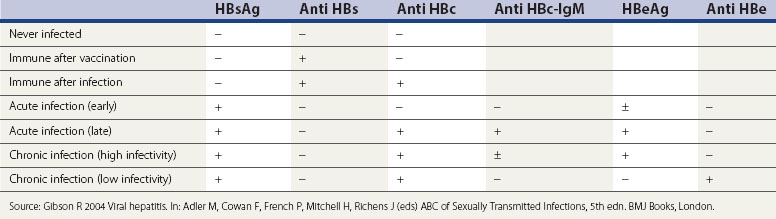

Viral Hepatitis

It should be noted that viral hepatitis is a notifiable disease in the UK, irrespective of the causative virus. Characteristics of the known hepatitis viruses are shown in Table 63.3.

Hepatitis B

Concurrent HIV infection increases the risk of progression to cirrhosis and death.

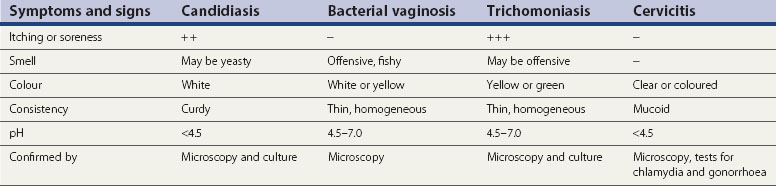

Vaginal Infections

The acidic milieu of the vagina (pH 4.5) is maintained by lactobacilli (Döderlein’s) which accounts for 95% of the bacteria found in the normal vaginal flora. This inhibits the overgrowth of other vaginal commensals under normal conditions. The substrate for lactic acid production is glycogen in the vaginal squamous cells, which is itself dependent upon the presence of oestrogen. Thus, prepubertal girls, pregnant women and postmenopausal women may have increased vaginal pH. Another more direct cause of increasing vaginal pH is the practice of douching, which should be discouraged. Smokers also have increased vaginal pH. The differential diagnoses of the common causes of vaginal discharge are summarized in Table 63.5.

Bacterial vaginosis

Diagnosis

Amsel criteria

At least three of the following four criteria need to be present for the diagnosis to be confirmed.

Candidiasis

Aetiology and clinical features

Vulval itch and/or soreness, vaginal discharge (typically curdy but may be thin, non-offensive), superficial dyspareunia and external dysuria are common complaints. There may be erythema, fissuring, oedema, satellite lesions and excoriation. None of these symptoms or signs are pathognomonic for vulvovaginal candidiasis. Many women may have other conditions, such as dermatitis, allergic reactions and lichen sclerosus. In addition, symptoms/signs are no guide to species (see Figure 63.16).

Trichomoniasis

Aetiology and clinical features

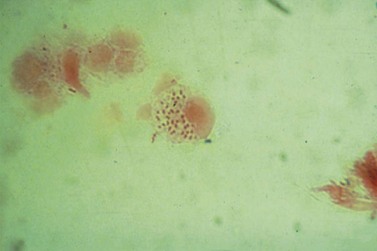

T. vaginalis is a flagellate protozoan (Figure 63.17). In women, the organism is found in the vagina, urethra and paraurethral glands. While the urinary tract is the sole site of infection in less than 5% of cases, urethral infection is present in 90% of episodes. In adults, transmission is almost exclusively sexual. Due to site specificity, infection can only follow intravaginal or intraurethral inoculation of the organism.

There is increasing evidence that T. vaginalis infection can have a detrimental outcome on pregnancy, and is associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight. However, further research is needed to confirm causality. Moreover, recent trials have found that treatment does not improve pregnancy outcome, and may be harmful. Screening of asymptomatic individuals for T. vaginalis infection is therefore not currently recommended (see Figure 63.18A,B).

Management and treatment

Screening for coexistent STIs should be undertaken in both men and women.

Ectoparasitic Infestations

Pediculosis pubis (Phthirus pubis)

Aetiology and clinical features

The crab louse Phthirius pubis (Figure 63.19) is transmitted by close body contact. The incubation period is usually between 5 days and several weeks, although occasional individuals appear to have more prolonged, asymptomatic infestation.

Scabies

Management and treatment

KEY POINTS

Health Protection Agency. All new episodes seen at GUM clinics: 1998–2007. United Kingdom and country specific tables, 2008.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections and Under 18 Conceptions. London: NICE; 2007.

World Health Organization. Global Prevalence and Incidence of Selected Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

Adler M, Cowan F, French P, Mitchell H, Richens J. ABC of Sexually Transmitted Infections, 5th edn. London: BMJ Books; 2004.

Avert website http://www.avert.org/

Department of Health. National Chlamydia Screening Programme Phase 3 Guide. London: Department of Health; 2005.

Gibson R. Viral hepatitis. In Adler M, Cowan F, French P, Mitchell H, Richens J, editors: ABC of Sexually Transmitted Infections, 5th edn, London: BMJ Books, 2004.

Johnson AM, Mercer CH, Erens B, et al. Sexual behaviour in Britain: partnerships, practices, and HIV risk behaviours. The Lancet. 2001;358:1835-1842.

Lewis DA, Latif AS, Ndowa F. WHO global strategy for the prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections: time for action. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83:508-509.

Wellings K, Nanchahal K, Macdowall W, et al. Sexual behaviour in Britain: early heterosexual experience. The Lancet. 2001;358:1843-1850.