CHAPTER 23 Non-endoscopic limited incision browlift

History

Unfortunately, all these methods have their deficiencies. In particular, the coronal browlift is plagued with a long incision which is feared by patients. Chronic dysesthesia and some scar alopecia are common. Cutaneous approaches leave scars which can be acceptable, but often are not. Browpexy procedures have proven to be inconsistent especially in the presence of mobile skin. Similarly, Knize’s procedure seems successful in some cases but not in others – presumably because of a fixation vector which is directed fairly laterally (Fig. 23.1).

From a surgical perspective, endoscopic brow lifting is an attractive option. It promises minimal incisions, minimal sensory change and little or no hair loss. Numerous authors have demonstrated the success of endoscopic brow surgery by measuring the amount of eyebrow elevation achieved from fixed orbital points. While clearly effective between the medial canthus and the lateral canthus, results at the lateral tail of the eyebrow can be unreliable. The example in Figs 23.2–23.4 illustrates the problem.

Physical evaluation

• Orbit: the size and shape of the orbit, the level of supra-orbital rim, and the relative prominence of the globe within the orbit.

• Hair: the thickness and color of hair and the level of the hairline.

• Forehead skin: the number and depth of the transverse forehead furrows and the depth of the frown lines.

• Eyebrows: the density and color of the eyebrow hairs, the level of the eyebrows in relation to the supraorbital rim and the upper lid sulcus, the relative height of the medial brow to the lateral brow, and the shape of the eyebrow arch.

• Upper eyelids: the level of the lids (normal, ptotic or retracted), the amount of soft tissue fullness above the upper lid sulcus, and the amount of visible eyelid between the eyelashes and the sulcus.

• Muscles: the strength and resting tone in the frontalis, the orbicularis oculi, and the frown muscle complex: the corrugator supercilii, the depressor supercilii, and the procerus.

• Symmetry: of orbital size shape and position, of eyebrow level, and of eyelid level.

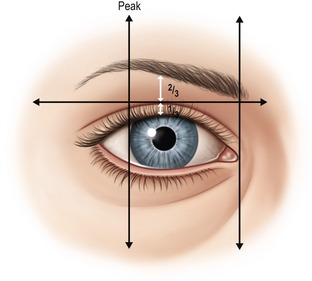

Many different professionals, including cosmetologists, anatomists and plastic surgeons have attempted to define the ideal position and shape of the eyebrow complex. This was reviewed by Gunter who concluded that the aesthetic ideal must be considered in relation to gender, ethnicity, orbital shape, eye prominence and facial proportions. Conventional descriptions of the “ideal eyebrow” in the modern era typically include the following (Fig. 23.5):

1. The medial eyebrow should be at or below the level of the orbital rim.

2. The medial border of the eyebrow should be above the medial canthus.

3. The eyebrow should rise gently, with a gentle peak at least two thirds of the way to its lateral end, and with this peak usually above the lateral limbus.

4. The lateral tail of the brow should be higher than the medial end.

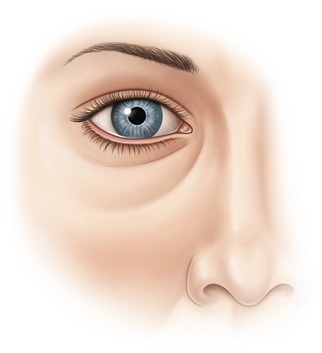

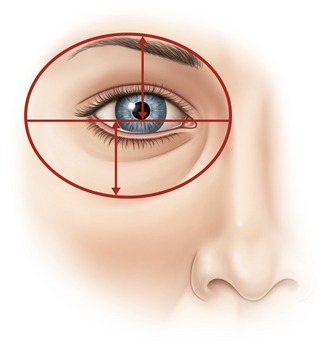

Gunter also observed that the eyebrow and the nasojugular fold create an oval with the pupil at the center of the oval. If the distance from center of the pupil to the eyebrow is reduced, the brow looks low (Fig. 23.6).

The amount of visible eyelid from the lash line to the palpebral fold should be approximately one-third the distance from the lash line to the eyebrow, and not more than one-half (Fig. 23.7).

Anatomy

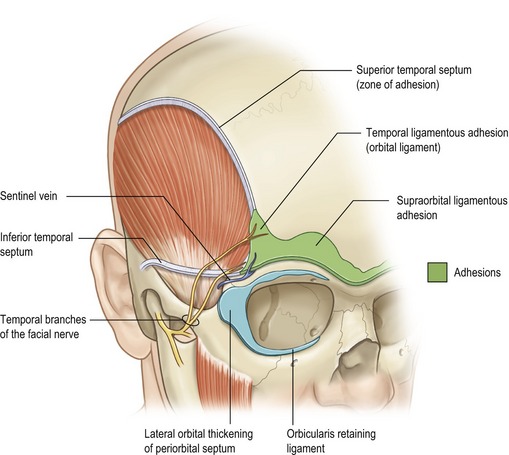

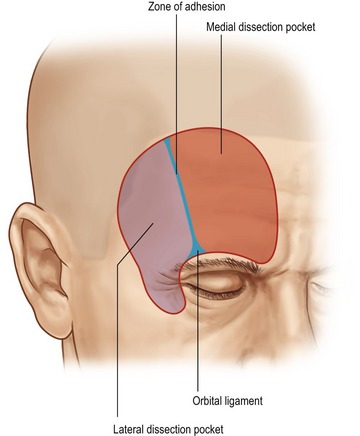

The temporal crest is a palpable line which separates the temporal fossa and the origin of the temporalis muscle from the forehead portion of the frontal bone. This is an area of transition where the deep temporal fascia covering the temporalis continues medially as the periosteum of the frontal bone. More superficially, the superficial temporal fascia continues medially across the forehead as the galea. These layers are all bound to bone along the temporal crest line in a zone of adhesion (Knize), also called the superior temporal septum (Moss et al.). Closer to the orbital rim, tethering fibers become stronger and more adherent, and the zone of adhesion widens to become the orbital ligament (Knize), also known as the temporal ligamentous adhesion (Moss et al.). Medially across the supraorbital rim there is further attachment of galea to bone (supraorbital ligamentous adhesion).

Also visible is the orbicularis retaining ligament which completely encircles the orbit, attaching the orbicularis oculi to the orbital rim. Laterally, this attachment broadens to become the lateral orbital thickening (Fig. 23.8).

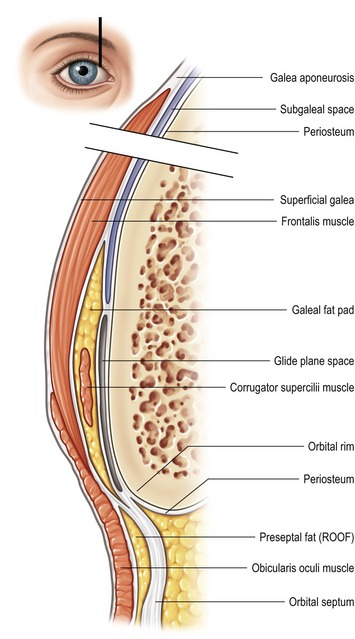

The galea aponeurotica splits into a superficial and deep portion, encompassing the frontalis muscle. As it approaches the orbital rim, the deep portion subdivides into three distinct layers: the first underlying the frontalis muscle and forming the roof of the galeal fat pad, a second forming the floor of the galeal fat pad, and a third layer tethered to bone (at the supraorbital ligamentous adhesion). Brow soft tissue (skin, orbicularis and galeal fat pad) move over a glide plane formed by the two deepest galeal layers (Fig. 23.9).

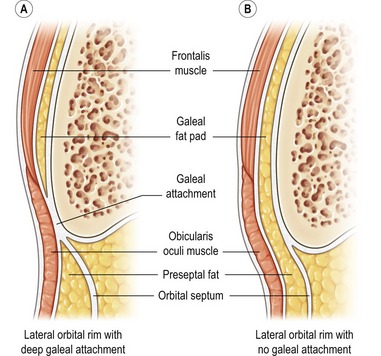

Laterally, where the frontalis dissipates, the galeal fat pad may or may not be separated from the preseptal fat (ROOF or retro-orbicularis fat), depending on the reflection of galea at the orbital rim. Knize has speculated that continuity of galeal fat and preseptal fat predisposes certain individuals to lateral brow ptosis (Fig. 23.10).

Fig. 23.10 Lateral orbital rim with deep galeal attachment and lateral orbital rim with no galeal attachment.

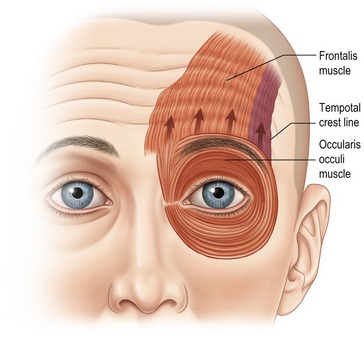

Frontalis imparts its elevation effect primarily on the medial and central brow, less so above the lateral canthus, and not at all over the eyebrow tail. This, then, is a set-up for lateral brow ptosis (Fig. 23.11).

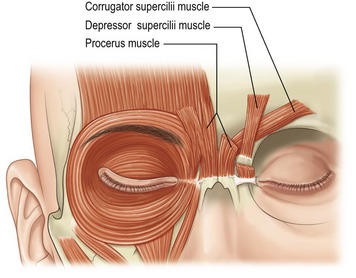

Medially, several muscular brow depressors take origin from bone and insert into soft tissue: corrugator supercilii, depressor supercilii, and the procerus (Fig. 23.12).

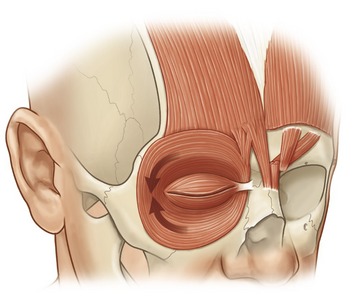

Laterally, the orbicularis oculi acts like a sphincter, pulling down the tail of the brow (Fig. 23.13).

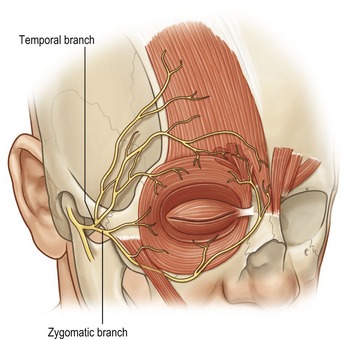

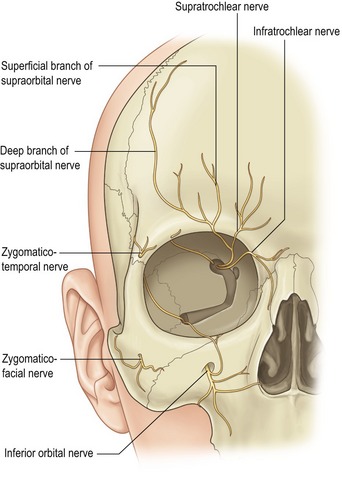

Nerves in the periorbital region include the temporal branch of the facial nerve (VII) (Fig. 23.14) and multiple sensory nerves (Fig. 23.15).

The supraorbital nerve leaves the orbit either through a notch in the rim or through a foramen above the rim. There is considerable anatomic variation, such that blind dissection can damage a nerve which exits through a supraorbital foramen. Because of this, some visualization of the supraorbital rim area is important during dissection of this area.

Deep branch of the supraorbital nerve

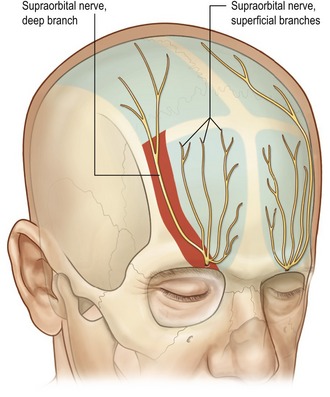

The supraorbital nerve divides into two branches. The superficial portion travels on the superficial surface of the frontalis innervating the central forehead. The rest of the scalp and top of the head is innervated by the deep branch which travels laterally and between the periosteum and the galea. Knize has described the anatomy of deep branch of the supraorbital nerve. It may be single, double or triple. In all instances, the deep branch runs in a 1 cm wide band which lies between 5 mm and 15 mm medial to the palpable temporal crest line (Fig. 23.16).

Technical steps

Preoperative markings are done with the patient in the upright position. The patient is asked to clench her teeth, making the temporalis muscle palpable. This helps delineate the temporal ridge which is marked. If visible, the sentinel vein (medial zygomatico-temporal vein) is marked (an X in the photo in Fig. 23.17). The expected course of the facial nerve, temporal branch is delineated, as it crosses the middle third of the zygomatic arch and courses superiomedially at the sentinel vein. The expected course of the supraorbital nerve, deep and superficial branches are then marked. The desired vectors of pull are marked. Although guidelines for these have been described, a customized approach is often more useful. With this method the planned vectors are usually more vertical than traditionally described.

The procedure is done under general anesthesia or local anesthesia with sedation. Local anesthetic containing epinephrine is injected into the planned incision, as well as around the orbital rim. A small strip of hair is shaved in a 1 cm strip immediately superior to the planned incision (Fig. 23.18). The incision is made parallel to hair follicles and a 1 cm wide strip of skin is raised from the underlying galea and superficial temporal fascia and is retracted posteriorly. This skin can be excised now or later.

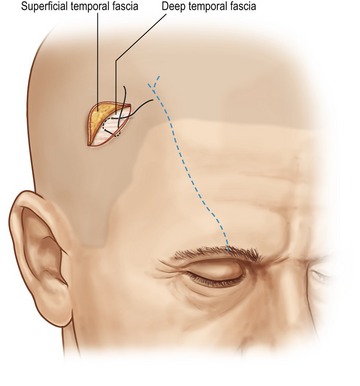

The lateral portion of the incision is then entered, spreading with scissors through the superficial temporal fascia down to the deep temporal fascia (Fig. 23.19). This dissection will be lateral to the expected course of the deep branch of the supraorbital nerve. The temporal pocket is then dissected under direct vision using a headlight or a lighted retractor. The sentinel vein is identified as the marker for the overlying branches of the facial nerve. If the dissection is kept deep on the surface of the deep temporal fascia, these nerve branches will be safe.

The medial pocket is then developed by spreading through the frontalis and galea, and utilizing a periosteal elevator, through periosteum to enter the subperiosteal plane (Fig. 23.20). This dissection will be medial to the expected course of the supraorbital nerve’s deep branch.

At this point a bridge of tissue will remain between the lateral and medial portions of the incision (Fig. 23.21). This bridge contains the deep branches of the supraorbital nerve and terminal branches of the anterior temporal artery and vein. It is not necessary to individually dissect out these structures.

After both pockets have been developed, they are connected from lateral to medial using a periosteal elevator in a blind sweeping motion. This maneuver changes anatomic planes from the temple (superficial to the deep temporal fascia), to the forehead (subperiosteal) (Fig. 23.22).

The zone of adhesion can now be completely divided down to the orbital rim.

Depending on operator preference, an endoscope can be inserted at this point to aid with orbital rim release. The author’s preference here is to use the endoscope, but with proper retraction and focused lighting, it is not absolutely necessary. A thorough release of the lateral orbital rim is completed down to the level of the zygomatic arch. The supraorbital rim is released medially past the supraorbital nerve. At this point some method of visualization is necessary to confirm safety of the supraorbital nerve trunk. The extent of medial release can be determined with traction placed on the flap. It is usually necessary to release 1 cm medial to the supraorbital nerve for satisfactory mobility of the lateral brow complex. Finally, the operator can insert a finger to confirm satisfactory mobility around the orbital rim (Fig. 23.23).

The scalp flap is then drawn superiorly and fixed into place. This is done through the lateral portion of the incision with two sutures placed from the superficial to the deep temporal fascia (Fig. 23.24). These sutures can be permanent or a long lasting absorbable such as 3-0 Monocryl. If a peak to the lateral third of the brow is desired, working through the medial portion of the incision fixation to bone can be done utilizing any available technique. LactoSorb tacks are simple and effective.

Lastly, the cut edges of galea are drawn together under some tension (Fig. 23.25). If the flap has been well mobilized, sutures will bunch up the galea at this point. The redundant, hair-bearing scalp skin, is conservatively excised enabling a tension free closure. The neurovascular bundle simply telescopes up under the closed scalp. A bupivacaine block is injected into the supraorbital nerve. A drain is not normally used. A light dressing is then applied.

Complications

Problems with this procedure are analogous to the endoscopic approach. Specifically, there is the potential for early hematoma, and for sensory or motor nerve injury. Because the incision is longer than with a pure endoscopic approach there is also the potential for minor alopecia formation. Should this develop, it can be watched for 6 months, and if persistent, can be corrected with simple excision (Fig. 23.26).

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• An accurate diagnosis is essential. This will determine if a browlift is necessary, if reshaping of the brow will help, and whether surgery to the eyelids is required.

• In the aging brow, the lateral tail drops the most, and is the hardest to lift. It is very easy to over-elevate the medial brow.

• Lateral brow elevation requires complete periorbital soft tissue release.

• Maintenance of lateral brow elevation completely depends on mechanical fixation

Pitfalls

• Imprecise dissection endangers the temporal branch of the facial nerve.

• Blind dissection of the supraorbital nerve will lead to damage if it exits the orbit through a supraorbital foramen.

• Inadequate periorbital soft tissue release will prevent brow elevation.

• Suturing scalp skin under tension leads to alopecia.

• Lack of appropriate fixation will result in loss of lateral brow elevation.

Summary of steps

1. Preoperative markings: temporal crest line, underlying nerves, customized vectors.

2. Incision: 1 cm posterior to the hairline, 6 cm long, crossing directly over the supraorbital nerve deep branch.

3. Dissection is done through two dissection pockets on either side of the neurovascular bundle.

4. Complete release of the zone of adhesion and orbital ligament.

5. Complete soft tissue release of lateral orbital rim and supraorbital rim.

6. Visualize and protect the supraorbital nerve trunk.

7. Confirm soft tissue release by visualizing preseptal fat (ROOF).

8. Suture fixation from superficial to deep temporal fascia.

10. Nerve sparing scalp excision.

11. Galeal closure under tension.

12. Scalp skin closure with no tension.

Chiu ES, Baker DC. Endoscopic brow lift: a retrospective review of 628 consecutive cases over 5 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:628–633.

Core GB, Vasconez LO, Askren C, et al. Coronal face lift with endoscopic techniques. Plast. Surg Forum. 1992;25:227.

Gunter J, Antrobus S. Aesthetic analysis of the eyebrows. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:1808–1816.

Guyron B, Kopal C, Michelow B. Stability after endoscopic forehead surgery using single-point fascia fixation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1988.

Isse NG. Endoscopic facial rejuvenation: endoforehead, the functional lift. Case Reports. Aesthet Plast Surg. 1994;18:21.

Knize DM. The forehead and temporal fossa anatomy and technique. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001.

Knoll B, Attkiss K, Persing J. The influence of forehead, brow and periorbital aesthetics on perceived expression in the youthful face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1793–1802.

Lemke BN, Stasior OG. The anatomy of eyebrow ptosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:981–986.

Miller TA, Rudkin G, Honig J, Elahi M, Adams J. Lateral subcutaneous brow lift and interbrow muscle resection: clinical experience and anatomic studies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:1120–1127.

Moss CJ, Mendelson BC, Taylor I. Surgical anatomy of the ligamentous attachments in the temple and periorbital regions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:1475–1490.

Paul MD. The evolution of the brow lift in aesthetic plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1409–1424.

Warren R, Endoscopic brow lift: five-portal approach. Nahai F, Saltz R. Endoscopic Plastic Surgery, 2nd edn, St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing, 2008.