Non-acute abdominal pain and other abdominal symptoms and signs

Introduction

The principal presenting symptoms of non-acute abdominal disorders are shown in Box 18.1. In addition, patients are often referred to a surgeon after discovery of an abdominal mass, obstructive jaundice or an iron deficiency anaemia caused by chronic blood loss. As ever, the history can provide 70% or more of the clues to the diagnosis, and so must be taken thoughtfully, accurately and with great care.

Pain

Character, timing and site of the pain

Key points in taking a history of abdominal pain are summarised in Box 18.2. Pain is highly subjective and the description will be coloured by the patient’s perception of it and its possible significance. Patients often use vague terms such as ‘indigestion’ and ‘dyspepsia’; these terms are imprecise, so what the patient actually means should be clarified by further questioning. Time-related features of the pain are often highly significant in formulating a differential diagnosis but will only be elicited by diligent enquiry. It is important to establish when a pain first began. Sometimes, asking when the patient was last completely well helps pinpoint the real onset. When presenting a case history, say ‘the pain began 6 days ago’ rather than, say, ‘it began last Thursday’.

Diseases causing non-acute abdominal pain—typical patterns

• Gallstones and gall bladder dysfunction. Biliary colic presents with irregularly recurrent bouts of severe pain which, though described as colic, characteristically last continuously for 1–12 hours. Severe and prolonged episodes may bring the patient into hospital. Pain is usually located in the upper abdomen—most often on the right side—and may radiate around to the back. It is often precipitated by rich or fatty foods and may be associated with vomiting

• Peptic ulcer disease. Typically there is intermittent ‘boring’ epigastric pain which recurs several times a year and lasts for days or weeks at a time. It is not as severe as biliary colic unless there is perforation, which presents acutely. Retrosternal ‘burning’ occurs in peptic oesophagitis and tends to occur after large meals and on lying down. The relationship of pain with food varies according to the site of the ulcer disease: duodenal ulcer pain is relieved by bland food and recurs 3–4 hours afterwards, typically in the early morning, whereas the pain of gastric ulcer and oesophagitis tends to be aggravated by food, especially if acidic or spicy. Peptic pain is generally relieved by antacids and virtually always by H2-blocking drugs (e.g. ranitidine) or proton pump inhibitors (e.g. omeprazole), this ‘trial of treatment’ providing evidence towards a diagnosis

• Chronic pancreatitis and carcinoma of pancreas. Either is typically associated with severe ‘gnawing’, persistent and poorly localised central pain which usually radiates through to the back and is often associated with anorexia and weight loss. The pain may be relieved by leaning forwards (‘the pancreatic position’). Early carcinoma of the pancreas, however, is usually painless

• Irritable bowel syndrome and constipation. These may cause a chronic symptom complex mimicking partial bowel obstruction and manifest by episodes of colicky pain. This is poorly localised, often ‘bloating’ pain, particularly post-prandially (after meals). Its intensity varies and it is often associated with transient disturbances of bowel function, particularly alternating diarrhoea and constipation. Passage of flatus or stool often temporarily relieves the symptoms

• Diverticular disease and Crohn’s disease. Partial bowel obstruction can occur with sigmoid diverticular disease or with small bowel Crohn’s disease. Symptoms are similar to those of complete bowel obstruction but more low-key. In incomplete bowel obstruction, there is often passage of some flatus or even faeces but the patient otherwise appears obstructed. The term subacute obstruction is meaningless and should be abandoned

• Chronic renal outflow obstruction (hydronephrosis) caused by stone, tumour or fibrosis. There may be a ‘dull’, poorly defined, fairly constant loin pain, which can radiate to the groin or genitalia and be accompanied by typical urinary tract symptoms, e.g. haematuria and dysuria. It is often aggravated acutely by high fluid intake

• Gynaecological conditions, particularly chronic pelvic inflammatory disease and ovarian tumours. These may reach the general surgeon because of poorly defined lower abdominal pain. A gynaecological history should be taken in female patients; pelvic examination may reveal the cause and ultrasound is usually diagnostic

• Non-surgical (i.e. ‘medical’) disorders causing abdominal pain. These include liver congestion in heart failure (common), splenic infarcts or diabetes (both uncommon but important), acute intermittent porphyria, sickle-cell anaemia or tertiary syphilis (very rare). Patients sometimes present with abdominal pain for which no organic cause can be found despite extensive investigation. In these, irritable bowel syndrome or sensitivity to certain foods, e.g. gluten or wheat protein, need to be considered. Only as a last resort should the pain be attributed to psychological disturbances

Non-acute abdominal pain in children

This is common. The main organic causes are: ‘infantile colic’ (sometimes due to cow’s milk allergy), irritable bowel syndrome in older children, chronic inflammatory bowel disease, recurrent streptococcal infections, and sometimes hydronephrosis caused by urinary tract obstruction. The so-called ‘periodic syndrome’ is characterised by recurrent episodes of poorly defined and inconsistent abdominal pain and/or recurrent vomiting, sometimes sufficiently severe for the child to require admission and intravenous fluids. Abdominal migraine with or without nausea, pallor, photophobia and lasting for up to 3 days is most common in the years before puberty. Psychosomatic abdominal pain may be the explanation if organic causes have been excluded and thus psychological and environmental factors, including the possibility of child neglect and abuse, should be explored (see Table 51.2).

Approach to investigation of non-acute abdominal pain

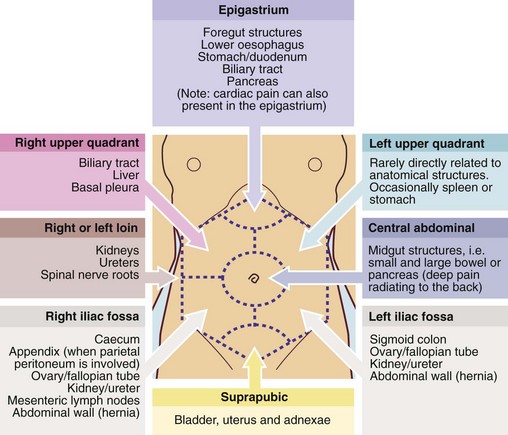

A differential diagnosis must first be made on clinical grounds (Box 18.3 and Fig. 18.1). The choice (and order) of investigations should be efficient and economical, after considering how each will support or help eliminate the most probable (and common) diagnoses and how it might influence management.

Dysphagia and odynophagia

The common causes of dysphagia are outlined in Box 18.4, p. 252. Pain on swallowing or odynophagia (usually provoked by both food and drink, particularly if hot) is a distinctive symptom highly suspicious of carcinoma.

Weight loss, anorexia and associated symptoms

The diseases which cause these symptoms may be grouped into four broad categories:

Fig. 18.3 Bimanual palpation of the abdomen

The posterior hand pushes forwards so that an enlarged viscus (usually retroperitoneal, e.g. kidney) or a mobile intra-abdominal mass is pushed onto the anterior examining hand. Note that this is not ballottement, which involves short, sharp palpation anteriorly, thus displacing ascites enabling a mass to bounce onto the examining hand

• Intra-abdominal malignancies, e.g. carcinoma of stomach or pancreas, metastatic disease in the liver or widespread across the peritoneal cavity (arising particularly from stomach, large bowel, ovary, breast or bronchus), bowel lymphomas

• ‘Medical’ conditions, e.g. alcoholism and cirrhosis, viral diseases (e.g. hepatitis or infectious mononucleosis), uncontrolled diabetes or thyrotoxicosis, malabsorption, renal failure, cardiac cachexia

• Psychological disorders, e.g. anxiety, depression, anorexia nervosa, bulimia

• Chronic visceral ischaemia, a very uncommon condition resulting from atherosclerotic narrowing of at least two of the three main visceral arteries—the coeliac axis and the superior mesenteric and the inferior mesenteric arteries—resulting in ‘fear of food’ and massive weight loss

Anal and perianal symptoms

Approach to investigation of anal and perianal symptoms

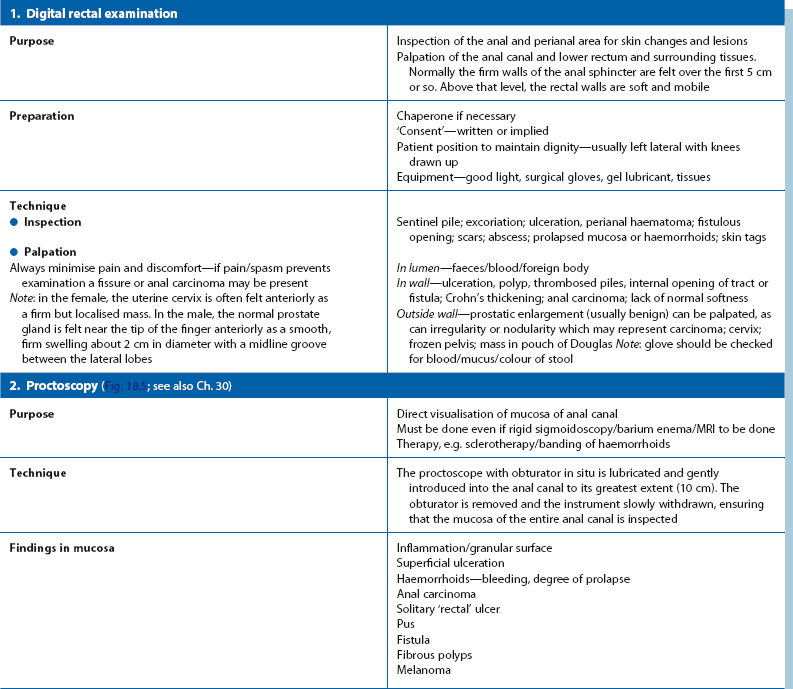

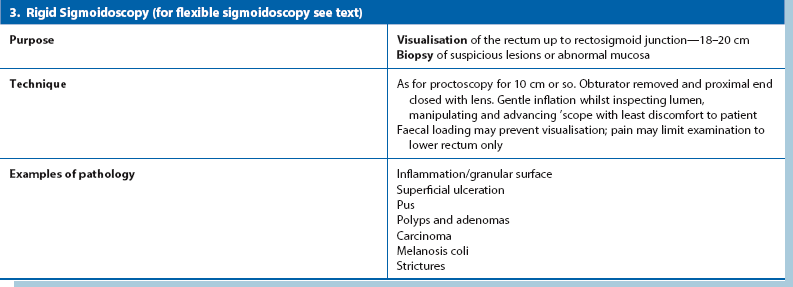

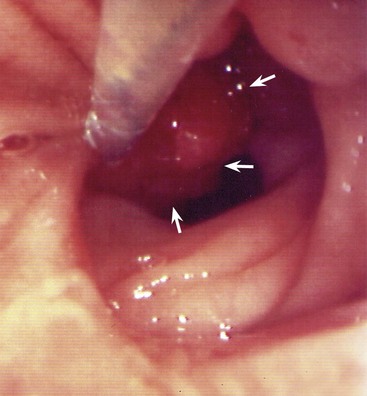

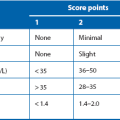

Inspection of the anal area, careful digital rectal examination (DRE) and proctoscopy are mandatory (Table 18.1 and Fig. 18.5). Further examination follows the principles described earlier. If pain makes these examinations impossible, a young patient can usually be assumed to have a fissure. In an older person or those with specific risk factors (e.g. HIV positive), carcinoma of the anus must be excluded by examination under anaesthesia. Haemorrhoids appear as bulging bluish masses beneath the anal mucosa. They all arise above the squamo-columnar junction or dentate line (‘internal piles’) but may later extend beneath the perianal skin (‘external piles’) or prolapse through the anus (‘intero-external piles’).

Fig. 18.5 Procto-sigmoidoscopy trolley

Typical layout of trolley prepared for proctoscopy and sigmoidoscopy in an outpatient clinic. Note the yellow waste bag on the left for contaminated swabs and waste and the paper bag on the right for waste wrapping from swabs, etc. Sigmoidoscopic biopsies are placed in a container of formol saline for fixation

A typical anal fistula appears as an inflammatory ‘nipple’ near the anal margin (see Fig. 18.6); it often exudes a discharge. In proctitis, the rectal mucosa is granular, erythematous and friable on proctoscopy. An anal or low rectal carcinoma is a discrete ulcerated lesion with an indurated (firm, woody) base and a thickened margin; diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Change in bowel habit, rectal bleeding and related symptoms

Normal bowel habit varies widely between individuals in frequency and consistency of stool. Transient changes in habit are usually insignificant but persistent change definitely require investigation. The differential diagnosis of a change in bowel habit is summarised in Box 18.5.

Frequency of defaecation and stool consistency

Chronic constipation or diarrhoea mark the extremes of change, although some patients develop an erratic bowel action. Any change may signify serious disease; the index of suspicion is further raised if there is rectal bleeding or tenesmus (for definition, see p. 256). Waking from sleep to evacuate the bowels should be treated seriously, especially if it occurs persistently.

Constipation

Severe constipation arises for four main reasons:

• Incomplete bowel obstruction, e.g. faecal impaction, an obstructing carcinoma or stricture in the bowel wall, or occasionally an extrinsic lesion such as ovarian cancer

• Loss of peristalsis, e.g. acutely due to drugs such as narcotics, antidepressants or iron, chronic diverticular disease, chronic laxative abuse

• Inadequate fibre intake or poor fluid intake, which decrease faecal volume and prolong intestinal transit time

• In bed-bound patients, multiple factors including immobility, diet, inadequate fluid intake, drug effects

Erratic bowel habit

Some patients develop an erratic bowel habit with bouts of constipation interspersed with episodes of frequency and looseness of stool. The most common cause is irritable bowel syndrome, which can be attributed to a heightened pain response in conjunction with a possible over-production of enteric gas. Sometimes symptoms include a marked gastrocolic reflex, i.e. a call to stool immediately after eating. In diverticular disease, constipation and ‘rabbit-pellet’ faeces are the dominant characteristics (see Ch. 29). However, there may be episodic diarrhoea during periods of inflammation or following release of proximal liquefied stool past partially obstructed solid faeces (spurious diarrhoea). Incomplete bowel obstruction of this type may also occur in carcinoma of the left colon, Crohn’s disease or faecal impaction.

Patients treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, particularly the cephalosporins, may develop antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. If caused by Clostridium difficile, this is known as pseudomembranous colitis in its severe form; the symptoms are due to changes in colonic bacterial flora (see Ch. 12).

Changes in the nature of the stool

Presence of frank blood, altered blood or mucus in the stool: Note: acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage is covered in Chapter 19.

Frank rectal bleeding: When a patient has seen blood in the stool, it is important to know the colour, i.e. fresh or altered blood, and also the relationship of the blood to the stool. Bright red blood usually indicates a lesion in the rectum or anus. When blood is clearly separate from the stool it suggests an anal lesion (see above). If blood is on the surface of the stool it suggests a lesion such as an adenoma (see Fig. 18.7) or carcinoma in the rectum or descending colon. These observations have limited diagnostic reliability and all rectal bleeding should be assumed to be caused by a tumour until proven otherwise.

Occult faecal blood loss: A persistent trickle of blood from the gastrointestinal tract may not alter the appearance of the stool but can cause serious iron deficiency anaemia. This ‘occult’ blood may be detectable only by chemical tests; these should be repeated three times to prevent false negatives.

Rectal passage of mucus or pus: Mucus (‘slime’) or pus may be passed alone or with the stool. The most common cause is irritable bowel syndrome. Villous adenomas typically secrete copious mucus, but this may also occur with rectal carcinoma. Mucus and pus may be noted in inflammatory bowel disorders and occasionally in diverticular disease. An anal leak of mucus may be a feature of haemorrhoids and causes itching (pruritus ani). A patient sometimes reports passing a mass of purulent material. This usually represents spontaneous discharge of a perianal or pararectal abscess, and will often be preceded by anal or perineal pain.

Iron deficiency anaemia

Approach to investigation of anaemia

Investigation of a patient with suspected iron deficiency anaemia has five main components:

• History—seeking sources of blood loss from the various tracts (see Box 18.6) and excluding inadequate iron intake. Previous gastrectomy may cause vitamin B12 deficiency and also diminished acid output, which may diminish iron absorption. Drug history—aspirin, other NSAIDs and corticosteroids may be the cause of chronic gastroduodenal blood loss. A history of drug treatment for peptic ulcer or antacids for ‘indigestion’ may also indicate a source of blood loss

• Physical examination—seeking an abdominal mass, an enlarged Virchow’s node in the left supraclavicular area (indicative of intra-abdominal malignancy), a rectal lesion or signs of a ‘medical’ cause

• Confirmation of iron deficiency anaemia and exclusion of common ‘medical’ causes of anaemia such as rheumatoid arthritis or chronic leukaemias—examine blood film, measure ESR, serum iron and transferrin, B12 and folate. When there is a ‘mixed’ anaemia, measuring iron stores in a bone marrow biopsy is the definitive method of diagnosing iron deficiency. Small bowel biopsies may demonstrate coeliac disease in a proportion of patients with simple anaemia without bowel symptoms

• Testing of specimens of stool for occult blood (at least three specimens)

• Pursuing clues that suggest the origin of bleeding with special investigations such as endoscopy and contrast radiology. When faecal occult blood is positive, colonoscopy is performed, looking for tumours, polyps, inflammatory bowel disease or angiodysplasias. If negative, this is followed by gastroscopy. Both can be performed in one session. If both are negative, it may be appropriate to proceed to small bowel contrast radiography, flexible small bowel enteroscopy or capsule endoscopy (see Ch. 5).

Obstructive jaundice

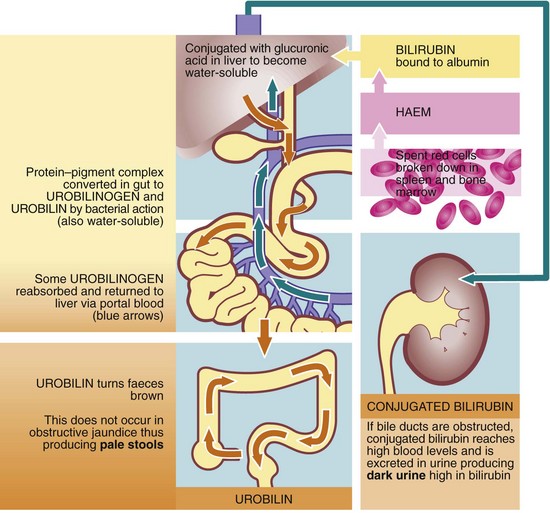

The normal enterohepatic circulation (Fig. 18.8)

The haem component of spent red cells is normally broken down to bilirubin (mainly in spleen and bone marrow), bound to albumin and transported to the liver. This relatively stable protein–pigment complex is insoluble in water and is not excreted in urine. In the liver, the complex is split and the bilirubin conjugated with glucuronic acid which makes it water-soluble, before being excreted into the bile canaliculi. The normal concentration of both conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin in the blood is very low. Bacterial action in the bowel converts conjugated bilirubin into colourless urobilinogen and pigmented urobilin which imparts the brown colour to normal faeces. Some urobilinogen is reabsorbed, passing to the liver in the portal blood, and is then re-excreted in the bile. The entire process is called an enterohepatic circulation (see Fig. 18.8). A small amount of urobilinogen escapes into the systemic circulation and is excreted in the urine, colouring it yellow.

History and examination of patients with obstructive jaundice

• Change in colour of urine and stools, i.e. dark urine and pale stools

• Drug history, e.g. oral contraceptive pill—potential for intrahepatic cholestasis

• Risk factors for viral hepatitis—blood product transfusion, intravenous drug abuse, tattoos, shellfish ingestion, sexual exposure

• Alcohol intake—if excessive, predisposes to pancreatitis and cirrhosis

• Symptoms associated with malignancy—anorexia, weight loss and non-specific upper GI disturbance is common in carcinoma of the pancreas, a disease of later life

• A history of inflammatory bowel disease predisposes to sclerosing cholangitis although this is uncommon

Examination

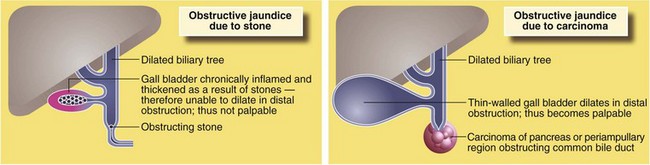

Courvoisier’s ‘law’ (see Fig. 18.9) was formulated in 1890 and states that obstructive jaundice in the presence of a palpable gall bladder is not due to stone (and therefore likely to be caused by tumour). The argument is that gallstones cause chronic inflammation leading to gall bladder fibrosis or intermittent stone obstruction leads to hypertrophy of the gall bladder wall, either preventing its distension. In malignancy, progressive obstruction occurs over a short period and the non-thickened gall bladder distends easily.

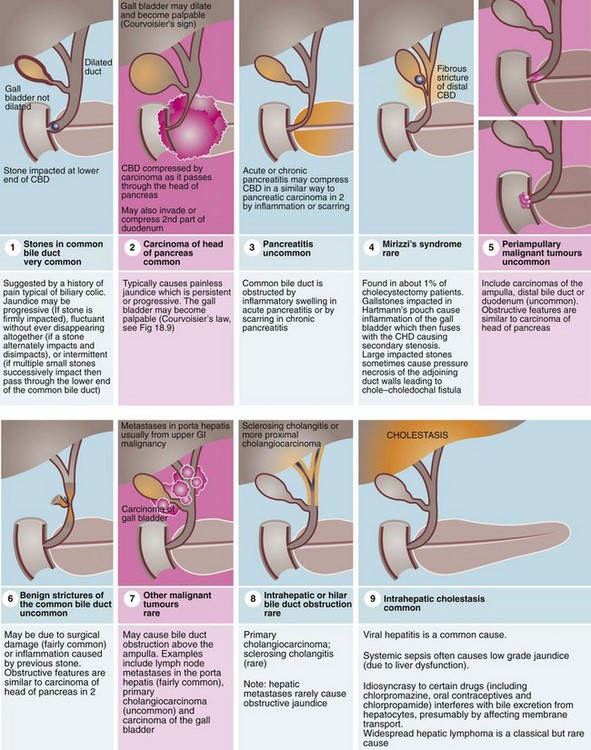

Particular attention is paid to the colour of stool found on rectal examination, as a pale stool is characteristic of obstructive jaundice. The urine in obstructive jaundice is usually dark yellow or orange from the presence of conjugated bilirubin, and froths when shaken owing to the detergent effect of bile acids. Conditions causing obstructive jaundice are illustrated in Figure 18.10.

Approach to investigation of jaundice

Blood tests

• Infective hepatitis should be excluded by serological screening for hepatitis B and C. A history of transfusion, intravenous drug abuse or travel to developing countries may increase the likelihood of an infection

• Confirm that the jaundice is obstructive by liver function tests, although these are not completely reliable. Obstructive jaundice is characterised by elevated plasma conjugated bilirubin and marked elevation of plasma alkaline phosphatase (liver isoenzyme). The transaminases, derived from hepatocytes, are usually only mildly elevated

• When biliary obstruction is intrahepatic (e.g. cholangiocarcinoma obstructing one duct) there may be a mixed biochemical picture with evidence of hepatocyte damage and duct obstruction. Liver function tests are an unreliable guide and liver ultrasonography is mandatory

• Mild jaundice is commonly found in patients with Gilbert’s syndrome, caused by a mild congenital abnormality of haemoglobin metabolism without serious significance

• Coagulation studies should be performed because of likely defects in clotting

• Tumour markers should be tested for in patients with a previous history of GI malignancy

Imaging

Hepatobiliary ultrasonography: This is the simplest means of demonstrating dilated intrahepatic ducts (see Fig. 18.11), liver secondaries, a dilated extrahepatic biliary system or gall bladder abnormalities including stones. Ultrasound is unreliable for demonstrating pathology in the lower part of the biliary tree, and although it may show gallstones or lesions in the head of the pancreas, it is unreliable for excluding them.

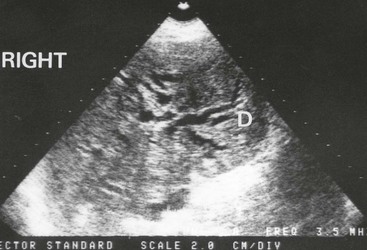

Fig. 18.11 Ultrasonogram showing dilated intrahepatic ducts

An ultrasound scan in an 80-year-old man with obstructive jaundice. This transverse section through the liver shows the characteristic ‘double-barrel shotgun sign’ D, with two parallel tubular structures representing major branches of the bile duct and portal vein. Normally, the portal vein is four times wider than the corresponding bile duct. Here they are the same diameter

Endoscopic and magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography

If ultrasound demonstrates dilated ducts, endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) is often the next investigation (see Fig. 18.12). It is now usual practice to drain an obstructed bile duct at the same procedure if practicable, by sphincterotomy and stone removal or by placing an intraluminal stent. This may be the definitive treatment for duct stones or inoperable carcinomas; for patients requiring operation, stenting may be used to allow jaundice to settle and liver function to improve, but stents can interfere with endoscopic ultrasound staging of cancers. The role of diagnostic ERCP has been largely superseded by magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography (MRCP), described in Chapter 5.

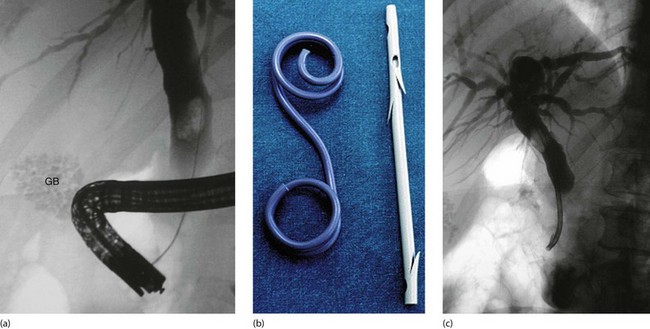

Fig. 18.12 Endoscopic stenting

(a) Diagnostic endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram (ERC) showing an enlarged common bile duct containing a single large stone. A collection of radiopaque gallstones is seen in the gall bladder (GB). (b) Two types of biliary stent: the pigtail type on the left and the notched variety on the right, as used in this patient. (c) Despite endoscopic sphincterotomy, the bile duct stone could not be retrieved so a tubular self-retaining stent has been placed to relieve the obstructive jaundice. The stone was successfully removed endoscopically on a later occasion

Principles of management of obstructive jaundice

Three categories of obstruction can be defined according to treatment options:

Potentially curable obstructions

These include bile duct stones and strictures as well as small tumours of the lower bile ducts, duodenum or ampullary region (periampullary tumours) (see Fig. 18.10, p. 260).

Small periampullary tumours may be amenable to complete excision, thereby relieving biliary obstruction and often achieving cure. Adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head is a common cause of obstructive jaundice but the prognosis is poor even after successful radical pancreatico-duodenectomy. If an operation for potentially curable malignant disease is planned, the precautions in Table 18.2 should be employed.

Table 18.2

Special precautions to be taken when operating on a patient with obstructive jaundice

| Potential complication | Pathophysiology | Prophylaxis |

| Infection | Obstructed bile is usually infected with aerobic gut organisms, and is under pressure. Instrumentation may precipitate ascending cholangitis, leading to sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction Spillage of infected bile during operation causes peritoneal contamination and risks intraperitoneal or wound infection |

Preoperative drainage of bile into the bowel by endoscopic sphincterotomy or stenting is sometimes used Prophylactic antibiotics against gut flora should be given |

| Endotoxaemia and renal failure | Endotoxins appear in the systemic circulation. These predispose to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) by activating components of the inflammatory cascade and may precipitate a systemic inflammatory response. Renal function is particularly vulnerable if renal perfusion is already impaired Postoperative ‘hepatorenal syndrome’ (i.e. acute renal failure) which manifests as oliguria and hyponatraemia |

Prophylactic antibiotics Ensure adequate hydration during any period of restriction of oral fluid throughout—preoperative intravenous fluids and osmotic diuretics during operation Insert urinary catheter to monitor output |

| Hepatic impairment | Biliary back-pressure on the liver causes defective clotting factor synthesis (even if vitamin K given) and defective hepatic metabolism of certain drugs Patients with chronic parenchymal liver disease withstand the stresses of major abdominal surgery and anaesthesia poorly |

Avoid drugs excreted by the liver. Give antibiotics to minimise endogenous endotoxin production |

| Fat malabsorption | Biliary obstruction causes diminished absorption of fats including fat-soluble vitamins such as vitamin K (a co-factor for prothrombin synthesis). This results in defective clotting | Monitor clotting Give parenteral vitamin K to improve prothrombin ratio, 24 hours preoperatively if possible; if necessary, fresh-frozen plasma perioperatively |

| Thromboembolism | Paradoxically, considering the clotting deficiency, postoperative deep vein thrombosis is common | Prophylactic subcutaneous low-dose heparin injections |

Obstruction due to incurable tumour

Such obstructions are caused by carcinoma of the pancreatic head (common), lymph node metastases in the porta hepatis (uncommon) and from carcinoma of the gall bladder (rare). Stenting is the palliative treatment of choice for the bile duct and, if necessary, duodenum. The alternative is palliative triple bypass surgery to bypass both biliary and duodenal obstructions (see Fig 24.3, p. 328).

Special risks of surgery in the jaundiced patient

Despite the fact that most obstructive jaundice can now be relieved preoperatively by stone removal or stenting, surgery must still sometimes be performed in a jaundiced patient. This poses a greater risk from preoperative and postoperative surgical complications, as shown in Table 18.2.

Abdominal mass or distension

Examination of an abdominal mass

The location of the mass, its relations to other structures, its mobility and its physical characteristics, such as size, shape, consistency and pulsatility give valuable information about the organ of origin and the likely pathology. Hernias, e.g. incisional, umbilical and sometimes interstitial (Spigelian) hernias (see Ch. 32), may present as localised swellings but they usually shrink or reduce completely when the patient is supine or under anaesthesia unless they are incarcerated.

Examination of masses in specific regions of the abdomen (see Fig. 18.1)

Mass in the right hypochondrium (right upper quadrant or RUQ): A right hypochondrial mass is usually of hepatobiliary origin. If so, it will be continuous with the main bulk of the liver to palpation and percussion. When the liver is diffusely enlarged, the inferior margin is regular and well defined and the consistency is usually normal. When infiltrated with primary or secondary cancer, it may be hard and irregular or the liver may appear diffusely enlarged. Carcinoma of the gall bladder is indistinguishable from hepatic cancer on palpation. Rarely, a Riedel’s lobe—a congenitally enlarged part of the right lobe—is mistaken for a pathological mass but is soft and mobile. Less commonly, a right hypochondrial mass is a diseased gall bladder. A mass continuous with the liver above and having a typical pear-shaped rounded outline is likely to be a mucocoele of the gall bladder. A more diffuse, tender mass may be an empyema of the gall bladder.

Epigastric mass: A mass in the epigastrium is usually due to cancer of the stomach or transverse colon or sometimes omental secondaries from ovarian carcinoma. Cancer involving the left lobe of the liver may also present like this (Fig. 18.13). These masses are usually hard and irregular, and are mobile or fixed according to the degree of invasion. Occasionally an epigastric mass consists of massive para-aortic lymph nodes due to lymphoma or testicular secondaries. A pulsatile epigastric mass is likely to be an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Mass in the left hypochondrium (left upper quadrant or LUQ): A cancer of the stomach or splenic flexure of the colon may present as a mass in the left hypochondrium. Tumour masses can usually be distinguished clinically from an enlarged spleen as the latter often has a discrete ‘edge’ and lies more posteriorly.

Mass in the loin or flank: A mass in the loin or flank is likely to be of renal origin and can best be felt on bimanual palpation (see Fig 18.3). Very rarely, a hernia occurs in the lumbar region; this reduces spontaneously as the patient rolls over.

Mass in the left iliac fossa: Masses here usually arise from the sigmoid colon. A hard faecal mass may be mistaken for cancer but it can often be indented like putty. A solid sigmoid mass is usually due to tumour or a complex diverticular inflammatory mass. Ovarian masses and sometimes eccentric bladder lesions may be palpable in either iliac fossa. These lesions, however, arise out of the pelvis and can often be pushed up on to the abdominal examining hand by digital pressure in the rectum or vagina (bimanual palpation—most effectively performed under general anaesthesia). Note that rectal examination is usually regarded as mandatory in a complete abdominal examination.

Hernias in the groin are common (see Ch. 32) and may be chronically irreducible (incarcerated). Occasionally, an interstitial (Spigelian) hernia develops above the groin in either iliac fossa. This presents a somewhat confusing picture on examination by virtue of its site and because the peritoneal sac herniates between the abdominal wall layers.

Suprapubic mass: Suprapubic masses usually arise from pelvic organs such as bladder or uterus and its adnexae. A palpable bladder is most commonly due to chronic urinary retention, easily confirmed on ultrasound. A distended bladder is dull to percussion and disappears on catheterisation. Bladder enlargement is usually symmetrical and may extend above the umbilicus. Only massive bladder tumours are palpable and these would be accompanied by urinary tract symptoms and urine abnormalities. Sometimes large bladder stones are palpable abdominally.

Mass in the right iliac fossa: The right iliac fossa is a common site for an asymptomatic mass. It may be due to unresolved inflammation of the appendix, surrounded by omentum and small bowel, forming an ‘appendix mass’ (see Ch. 26, p. 342). There is usually a recent history of right iliac fossa pain and fever. Carcinoma of the caecum may become very large without causing obstruction because the caecum is large and distensible, and the faecal stream at this point is semi-liquid. Thus, caecal carcinoma often presents with an asymptomatic mass, and iron deficiency anaemia. Crohn’s disease of the terminal ileum often presents with a tender mass, usually with typical symptoms of pain and diarrhoea.

Central abdominal mass: A central abdominal mass may originate in large or small bowel, be a result of malignant infiltration of the great omentum, or if they are large, from retroperitoneal structures such as lymph nodes, pancreas, connective tissues or the aorta. A common central abdominal mass is an abdominal aorta aneurysm. Aneurysms nearly all appear over 60 years of age and usually arise just above the aortic bifurcation (at umbilical level). A characteristic feature is expansile pulsation; other solid masses may transmit pulsation from large vessels nearby, but those masses are not expansile.

Rectal mass and findings on pelvic examination: An abdominal or pelvic mass may be palpable solely on rectal (or vaginal) examination. The mass may be a cancer of rectum or in the loop of sigmoid colon in the pelvic cavity; the latter is unlikely to be visible on sigmoidoscopy. Sometimes, secondary deposits from an impalpable tumour in the upper abdomen may seed the pelvic cavity. This may produce a hard anterior lump or even a solid mass filling the pelvic cavity (frozen pelvis). Frozen pelvis can also occur with endometriosis or local spread of a carcinoma of cervix or, rarely, prostate.

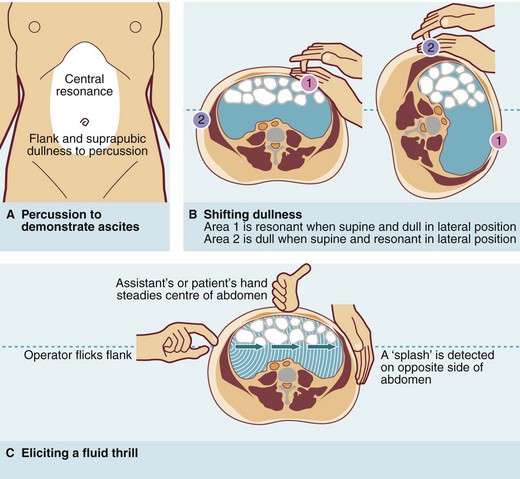

Interpretation of a finding of ascites

Ascites is defined as a chronic accumulation of fluid within the abdominal cavity and has many causes, some malignant and some non-malignant. Ascites can usually only be recognised clinically when the volume exceeds 2 litres, but even then it is easily overlooked. Dullness to percussion in the flanks and suprapubic region with central resonance is suspicious of ascites and should be followed by an attempt to elicit a fluid thrill or ‘shifting dullness’ (see Fig. 18.4).

Approach to investigation of an abdominal mass or distension

Radiology

A chest X-ray should be performed if malignancy is suspected. Ultrasonography or CT scanning (see Fig. 18.14) is useful for demonstrating the size and origin of a mass. For pelvic masses, transvaginal or transrectal ultrasound is often the investigation of first choice although MRI is often helpful. CT scanning is most valuable for defining masses in the retroperitoneal area, e.g. pancreas, aorta or kidneys, but may be the preferred investigation for suspected large bowel cancer, particularly in frail patients. Ultrasound or CT scanning can be used to guide needle biopsy or aspiration cytology precisely. Contrast studies, e.g. barium meal, barium enema or intravenous urography, may be indicated by the clinical findings.

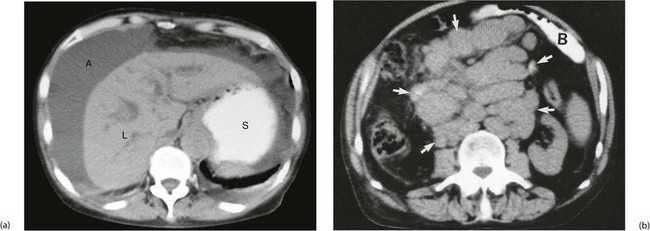

Fig. 18.14 CT scans showing gross ascites and enlarged lymph nodes

In (a) note the darker grey homogeneous shadow of fluid A around the liver L and the contrast in the stomach S. (b) Retroperitoneal mass of lymph nodes due to lymphoma. This CT scan was taken to assess the stage of spread of a known lymphoma. This 40-year-old woman presented with a large rubbery lymph node mass in her neck and was also found to have a large central abdominal mass. Abdominal CT scanning showed an enormous mass of lymph nodes (arrowed). Small bowel B is seen anteriorly, enhanced by orally administered contrast material