Non-acute abdominal and urological problems in children

Introduction

The acute conditions described in Chapter 50 are largely congenital disorders presenting in the neonatal period, whereas non-acute conditions present across the whole of childhood. The most common referrals are hernias and associated problems, abnormalities of testicular descent and foreskin problems. Less often, surgeons manage chronic or recurrent abdominal pain, chronic constipation, rectal bleeding, an abdominal mass or rectal prolapse. Many children present first to a paediatrician and are referred to a paediatric or general surgeon.

Problems with the groin and male genitalia

Hernias and associated problems

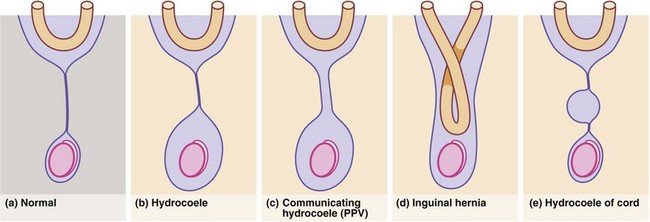

The processus vaginalis normally closes spontaneously soon after birth. Persistence causes three common problems in boys: patent processus vaginalis (PPV), hydrocoele and inguinal hernia, which may all present as inguinal or scrotal swellings, usually in babies and pre-school children (Fig. 51.1).

Hydrocoele

Non-communicating hydrocoeles are mostly seen in neonates and young babies (Fig. 51.2). The usual type is a scrotal swelling resulting from incomplete reabsorption of fluid within the tunica vaginalis after closure of the processus vaginalis. There may be a separate hernia present. These so-called ‘primary hydrocoeles’ sometimes appear following a viral illness. Rarely, a secondary hydrocoele results from testicular trauma or torsion, epididymitis or a testicular tumour.

Inguinal hernia

Inguinal hernias in children arise because the processus vaginalis fails to close after testicular descent; they are true congenital abnormalities. Anatomically, they are the same as indirect inguinal hernias in adults (see Ch. 32) but without a substantial abdominal wall defect. The incidence in infants ranges from 1% to 4.4%, with a male preponderance of 4 : 1; 98% are indirect. The incidence in premature neonates is 30% and the overall incidence is increasing in line with the number of premature neonates surviving.

Inguinal hernias may become acutely irreducible and painful, sometimes with obstructive symptoms such as vomiting (see Ch. 50). In these cases, there is a real risk of testicular necrosis and/or strangulation of the hernia contents, e.g. bowel or ovary (see Fig. 50.10). In known hernias, parents should be instructed to bring the child to hospital for urgent herniotomy if it becomes incarcerated to prevent these risks.

The standard operation is inguinal herniotomy, a common general paediatric operation. In babies and children, this involves separating the peritoneal sac from the cord (or round ligament), ligating it at the external ring and removing it. There is rarely any need to perform a repair (herniorrhaphy); see Figure 51.3. The incidence of an undiagnosed contralateral hernia in boys is between 1 : 8 and 1 : 13 but contralateral groin exploration is no longer performed in the UK.

Umbilical hernia

Many newborn babies have umbilical hernias, particularly if premature (Fig. 51.4), but the defect usually cicatrises and resolves during the first 2 years of life; they are common in Afro-Caribbean babies and can run strongly in families. Small umbilical hernias may undergo spontaneous closure up to 4–5 years of age. Rarely, they become incarcerated or strangulate. Indications for repair are symptoms, persistence beyond 5 years and perhaps social pressure to prevent teasing. The size of the abdominal wall defect should be determined; large defects (> 2 cm) are less likely to close spontaneously, although very large swellings may have small abdominal wall defects likely to close spontaneously. It is important to differentiate umbilical hernias from epigastric hernias which do not close spontaneously. At operation, a small subumbilical ‘smile’ incision allows emptying and ligation of the peritoneal sac and placement of a few absorbable repair sutures. The umbilical skin is usually sutured to the repair to restore its normal recessed appearance.

Testicular maldescent

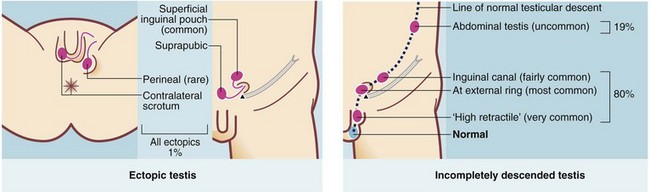

The normal mechanism of descent is not fully understood but does occur in two phases. Migration from the gonadal ridge to the internal inguinal ring depends on shortening of the gubernaculum, driven by Müllerian inhibiting substance (MIS). This phase is not androgen-dependent, unlike the second phase of descent from internal ring to scrotum. A maldescended testis may arrest anywhere on its path of descent. About 20% lie within the abdomen but 80% lie in the groin area, in the inguinal canal or usually outside the external ring in the superficial inguinal pouch or upper scrotum. In addition, 1% of testes are deflected and lie ectopically. Second phase maldescent can result from the testis being structurally abnormal, rather than any abnormality being caused by maldescent. The common sites of incomplete descent or ectopia are shown in Figure 51.5.

• Neoplasia—carcinoma-in-situ is present in 2% of undescended testes and maldescent has up to 10 times the normal risk of testicular malignancy (although the risk is still small); if surgical correction is done sufficiently early, it may reduce this risk but the principal purpose is for the patient to perform self-examination and report lumps in later life. Long-term follow-up after orchidopexy is desirable. Seminomas are the most common tumour (60%) and usually present between 20 and 40 years of age. It is important to inform the parents of the increased risk of malignancy and to reinforce the importance of testicular self-examination in adult life

• Subfertility—maldescended testes exhibit incomplete maturation of seminiferous tubules, leading to sperm abnormal in quantity, form or motility. This may be by virtue of being at normal body temperature instead of at least 1° cooler in the scrotum. Early orchidopexy helps maturation of the tubules and spermatogenesis, ideally between 6 and 12 months of age. Patients with unilateral maldescent have more subfertility and lower sperm counts. Those with bilateral intra-abdominal testes have the most subfertility

• Torsion—incompletely descended testes are abnormally mobile. Torsion of the testis, actually torsion of the spermatic cord, causes strangulation of blood supply, testicular necrosis and later atrophy. Torsion sometimes occurs during intrauterine life but may happen at any age. Intrauterine or neonatal torsion occurs proximal to the reflection of the tunica vaginalis (i.e. extravaginal). Infarction results in atrophy and loss of the testis so that at laparoscopy, only blind-ending testicular vessels and vas deferens are found. The condition occurs bilaterally in up to 30%

• Psychological—normal genitalia are important in the development of body image, gender acceptance and personality in adolescence. Orchidopexy at an early age provides reassurance to the child and parents

Boys should be examined regularly from birth right through school age to identify maldescent and allow timely orchidopexy. Periodic examination is needed because unequivocally descended testes can later ascend and parents and doctors should be alert to this possibility. There may be a fibrous band within the processus vaginalis preventing elongation of testicular vessels as the boy grows. The resulting ‘stationary’ testis appears to ascend, and no longer comes comfortably into the scrotum.

Renal, vesical and urethral abnormalities

About a third of all congenital anomalies affect the genitourinary tract. These include abnormalities of kidney, renal calyces or pelvis and ureters. Anomalies of the bladder and urethra complete the spectrum of paediatric urogenital problems, which may present at birth but need long-term follow-up, often into adulthood. Around 90% of renal tract abnormalities can now be detected at an antenatal 12- or 20-week scan, allowing parents to be prepared for postnatal management. The most common ones are hypospadias, pelviureteric junction (PUJ) obstruction and vesicoureteric reflux (VUR). Renal parenchymal disorders are less common. Some disorders present later, including unilateral renal agenesis, horseshoe kidney and polycystic kidneys (see Table 39.1).

Renal dysplasia

In renal ectopia (see Fig. 39.5), the kidney lies in an abnormal position in the pelvis, or abdomen. Renal ectopia can be discovered incidentally or associated with other anomalies such as anorectal malformations.

Abnormal fusion of the developing metanephric masses during the first two months of fetal life results in a horseshoe kidney (see Fig. 39.4). This may cause hydronephrosis by PUJ obstruction or be discovered incidentally at any age. Skeletal and cardiovascular abnormalities occur in at least a third; girls with Turner’s syndrome often have a horseshoe kidney.

Vesicoureteric reflux (VUR)

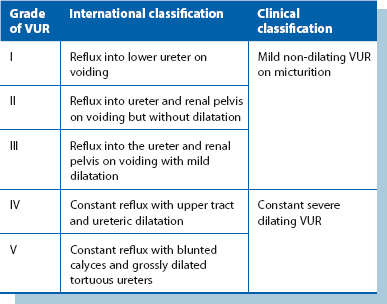

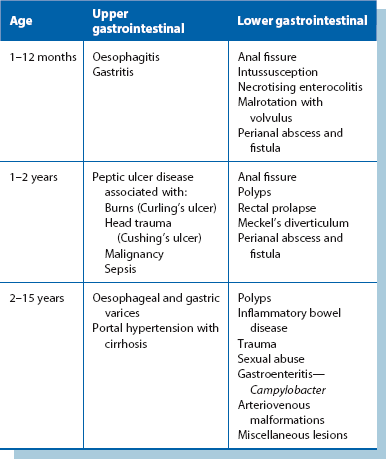

Any anatomical or functional urinary tract abnormality predisposes to infections. This is particularly true in children, where the commonest predisposing abnormality is vesicoureteric reflux, i.e. retrograde flow of urine from bladder to kidneys. This exposes the upper tracts to the greater range of pressure variation of the lower tract and to ascending infections. The causes are complex but in essence there is a faulty mechanism at the junction of ureter and bladder (vesicoureteric junction), see Box 51.1. Reflux is classified severities ranging from I to V (see Table 51.1).

Pathophysiology

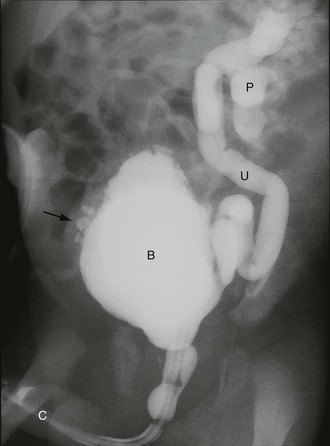

Reflux of sterile urine into the pelvicalyceal system during early childhood probably causes impaired renal development and function. Mild, non-dilating VUR (grades I to III; see Table 51.1) causes little damage but severe (dilating) VUR (grades IV and V) may cause renal scarring and reflux nephropathy, which may progress to irreversible renal damage if untreated (Fig. 51.6). If both kidneys are involved, this eventually results in renal insufficiency and hypertension. Scarring typically occurs apically in the kidneys. Loss of the normal conical shape of the papillae allows intrarenal reflux, which in the presence of infection results in pyelonephritis and renal scarring.

Fig. 51.6 Vesicoureteric reflux

Micturating cysto-urethrogram (MCUG) in a child with recurrent urinary tract infections. The bladder B is trabeculated (diverticula arrowed). On voiding, the left ureter U and pelvicalyceal system P filled with contrast as a result of severe dilating vesicoureteric reflux. This is defined as grade V reflux

Clinical presentation and investigation

In a child with urinary tract infection, clinical examination seeks evidence of abnormal external genitalia, spina bifida and impaired perineal innervation (sensation and anal sphincter tone). To demonstrate reflux, the sequential investigations are ultrasound scan, micturating cystography, and isotope scans using DMSA and MAG3, coupled with indirect radionuclide cystography. Micturating cystography should only be used in selected cases (Fig. 51.6); there is a 1% risk of pyelonephritis and the test is stressful for child and parent. It is the gold standard for demonstrating VUR and excluding posterior urethral valves but involves instilling contrast into the bladder via a urinary catheter which is then removed and X-rays taken during voiding. The radiological grades of severity are shown in Table 51.1 and provide a useful guide to the likelihood of future renal damage. Severe dilating VUR requires isotope studies: 99mTc DMSA, bound to renal tubules, shows differential renal function and scarring within renal parenchyma. In older children, an excretion MAG3 scan and indirect radionuclide cystogram shows differential function, reflux and sites of urinary tract obstruction.

Hypospadias and epispadias

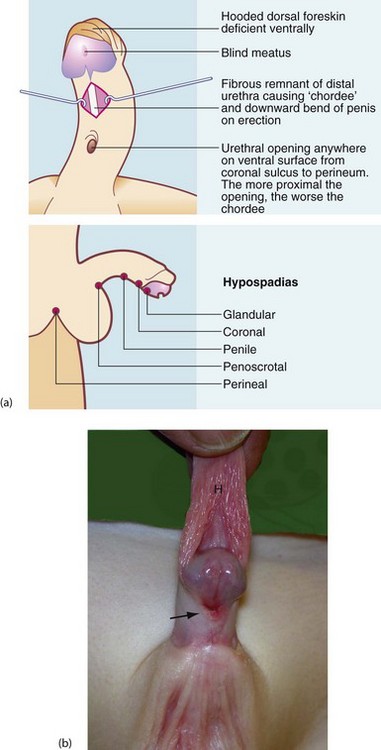

Hypospadias is a common congenital abnormality of penis and urethra. It occurs in 1 in 125–300 male births and is increasing in incidence. The distal urethra fails to develop normally, so the urethral meatus lies somewhere along the ventral surface of the penis between glans and perineum (see Fig. 51.7). The urethral remnant distal to the meatus is fibrotic, often causing the penis to bend downwards or sideways on erection, known as chordee. The more proximal the meatus, the worse the chordee. In addition, the ventral part of the foreskin is absent, giving a hooded appearance. Distal hypospadias is more common, accounting for about 85%, with the urethral opening between glans and the mid-shaft with minimal chordee.

Abdominal problems

Chronic and recurrent abdominal pain

Chronic or recurrent abdominal pain is common in children of school age but no cause is usually discovered and the problem gradually resolves (Box 51.2). Children may be referred to a surgeon if an organic problem seems likely, but psychological factors are fairly common. The common organic causes are constipation, hydronephrosis, inflammatory bowel disease and gallstones associated with haemolytic anaemia.

Chronic constipation

In severe constipation, it is important to investigate for cystic fibrosis, hypothyroidism and Hirschsprung’s disease (Ch. 50, p. 619). If these can be excluded, the child may require an operation such as anterior resection for redundant non-functional rectum or the creation of a conduit into the colon to allow antegrade enemas.

Gastrointestinal bleeding in children (Table 51.2)

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Rectal bleeding in neonates is most often due to anal fissure, necrotising enterocolitis or malrotation with volvulus. Rectal bleeding is a common problem in older infants and children; the causes are summarised in Table 51.2 and include perianal abscess and fistula, anal fissures, large bowel polyps, rectal prolapse and Meckel’s diverticulum.

Anal fissure: Anal fissure occurs at any age during infancy and childhood and is probably initiated by straining to pass a large hard stool. This splits the anal mucosa in the midline posteriorly or anteriorly. Anal fissures can also develop after severe diarrhoea. The main symptoms are pain at defaecation and a small amount of bright red blood on the stool or leaking out immediately after defaecation. The condition is readily diagnosed when digital rectal examination is found to be impossible because of extreme tenderness; the posterior end of the fissure may sometimes be seen by parting the buttocks. Treatment is conservative, with medical treatment of constipation and management of painful defaecation. Anal skin tags often develop following healing of an anal fissure.

Polyps: A juvenile hamartomatous polyp is a common cause of rectal bleeding. These are nearly always solitary and usually occur in the rectum or sigmoid colon. Polyps may present with intermittent rectal bleeding in a child without constipation; as pain on defaecation without an anal fissure; or by prolapsing through the anus. The polyp may be palpable on digital examination and is confirmed on proctoscopy; it can then be suture ligated and resected. If no polyp is visible, colonoscopy is performed and identified polyps removed by snare. Juvenile polyps are almost never malignant, nor do they recur. Familial adenomatous polyposis may present in childhood with rectal bleeding. As described in Chapter 27, polyps of this type inevitably turn malignant from about the age of 16.

Rectal prolapse: Transient rectal prolapse is a common and alarming childhood problem, usually during the first 2 years. The common cause is excessive straining during defaecation. Prolapse may be a presenting feature of cystic fibrosis because there is less mucus in the bowel and the mucus is thick and sticky. In addition, thick mucus often obstructs exocrine pancreatic secretion, impairing fat digestion. Most prolapses can be gently manipulated back without pain although they frequently recur unless the stool is kept soft and the child can open the bowels without straining. If the problem is persistent or recurrent, proctoscopy and sigmoidoscopy are indicated. A rectal polyp is occasionally responsible. If simple stool-softening measures fail to prevent recurrence, submucosal injections of hypertonic saline or phenol in oil have been used to induce fibrosis. In the rare event of failure, a subcutaneous circumanal suture may be inserted.

Perianal abscess: This is common in infants and results from infection of an anal gland, as in adults. The abscess points 1–2 cm from the anal verge. Drainage alone would convert this into a fistula so correct treatment involves opening the tract entirely under general anaesthesia, as in adults.

Meckel’s diverticulum: A Meckel’s diverticulum is present in less than 2% of the population. It represents the embryological remnant of the vitello-intestinal duct which joined the fetal midgut and the yolk sac. It is situated on the antimesenteric border of the distal ileum about 60 cm from the ileocaecal junction. They are usually asymptomatic.

A Meckel’s diverticulum with a narrow neck may become inflamed like appendicitis and cause similar symptoms and signs (see Fig. 26.4, p. 345); the diagnosis is only made at operation. As with appendicitis, the complications are perforation and peritonitis. Meckel’s diverticulitis is uncommon in children under 10 years.

Abdominal mass

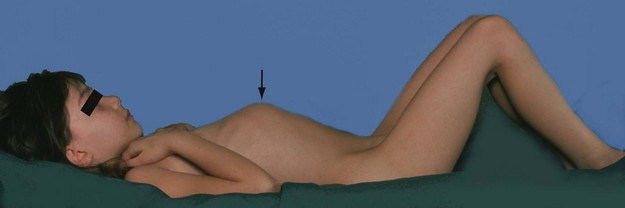

Nephroblastoma (wilms’ tumour)

Nephroblastoma presents in early childhood, with 80% presenting before the age of 5, at a median age of 3.5 years. The tumour arises from embryonal renal tissue in the kidney. Tumours are locally invasive and metastasise to regional nodes, liver, lungs and bone. Often, a large abdominal mass is noticed by the mother as the child is bathed (see Fig. 51.8). The mass is sometimes so large as to obscure its site of origin. Less common presenting features include haematuria, classically after trivial trauma, anorexia, weight loss, pyrexia and hypertension. Diagnosis is by clinical examination, and tumour size and characteristics are shown by ultrasonography or CT scan. The diagnosis is confirmed by Trucut biopsy.