CHAPTER 58 Nipple–areola reconstruction

Physical evaluation

• Unilateral reconstruction, anatomic symmetry (opposite nipple position and size; opposite NAC texture and color and size), need for secondary contralateral surgery.

• Previous breast mound scars (from mastectomy, biopsy, reconstruction).

• The vascularity and thickness of breast mound.

• The size of the reconstructed breast.

• The presence or absence of a well-defined fold.

• The desired final breast appearance.

• Medical history: specifically diabetes/vascular disease/smoking and other co-morbidities.

• Body and breast morphology (breast dimensional analysis).

• Size of opposite breast/plan of opposite breast (prophylactic mastectomy).

Technical steps

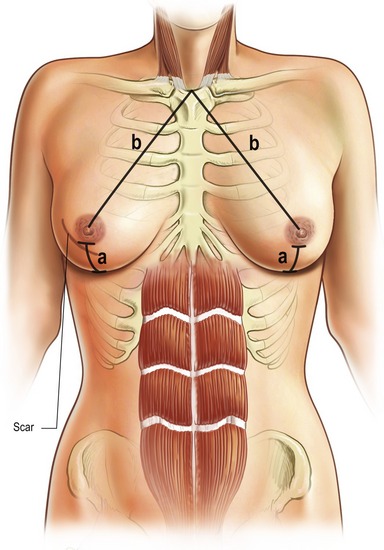

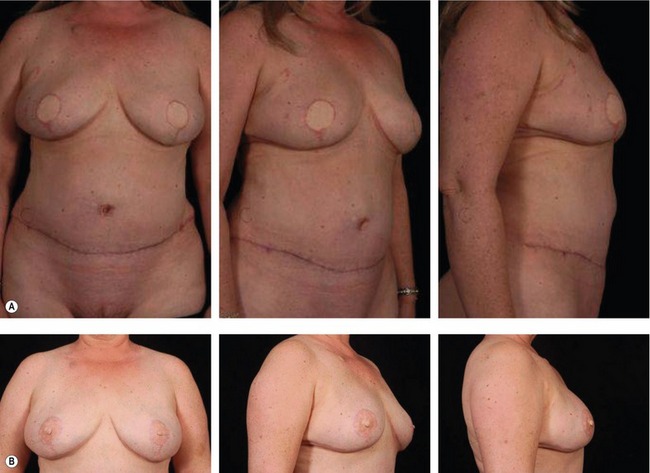

When the patient has agreed to proceed with nipple–areola reconstruction, the patient and the plastic surgeon must determine the optimal position. Specific identifiable landmarks help to determine the proper nipple areolar position visually and geometrically. These include the level of the nipple areola, the triangles with the sternal notch and the umbilicus and the nipple areolar position relative to each breast and to the inframammary fold (Fig. 58.1).

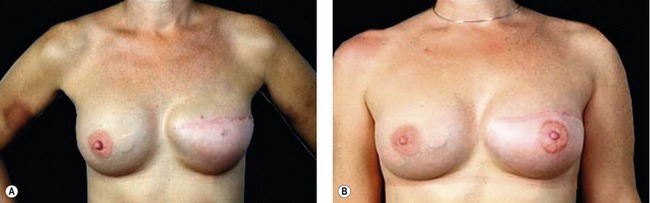

The nipple–areola position is determined visually with the patient in a standing position and the shoulder relaxed without abduction. In addition to measurement, visually the NAC is centered on the breast at the point of maximal convexity and projection, symmetric with the opposite NAC. This is why simultaneous contralateral surgery is not recommended as final shape and NAC position of the contralateral breast will change again.

Nipple–areola reconstruction is usually performed as a delayed procedure and can be either under local or general anesthesia and it is done on an outpatient basis. Several technical options are available for nipple and areolar creation. The method selected depends on the size and color of the opposite nipple and areola, the type of breast mound on which it is placed and the patient’s and surgeon’s preference (Table 58.1).

Nipple reconstruction

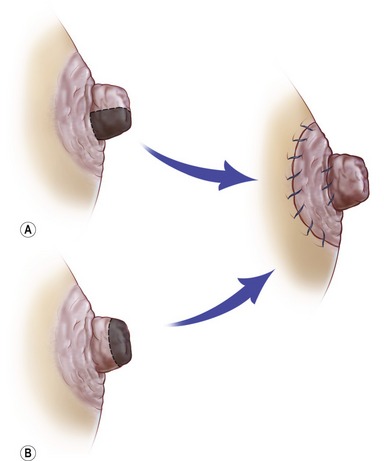

When the contralateral nipple is of adequate size (projected greater than diameter of areola and the patients are accepting, a composite graft can be taken from the opposite nipple (Fig. 58.2). It comes from the lower one half of the nipple or the tip, depending on its shape. This graft is sutured to the central portion of the de-epithelialized areola site and generally takes well. Most patients are not candidates for nipple-sharing reconstruction, and many patients fear donor site morbidity, including diminished projection of the donor site, risks of diminishing the sensitivity, and transfer of potentially malignant ductal tissue. Other composite graft donor sites, such as ear lobule and toe pulp, have been reported but they are generally not as satisfactory.

In most techniques (with the exception of the double opposing tab flap), the key to success is designing the flap base away from the mastectomy incision. The flap should have adequate dimensions to provide adequate height for the nipple mound. In patients who have undergone breast reconstruction by a flap, the local flap for nipple–areola reconstruction will be based, when it is feasible, on site selection on the surface of the flap where healthy full-thickness tissue will be available for nipple reconstruction. In the patient who has undergone reconstruction by immediate implant or expander-implant, the skin envelope is thin and the resultant flaps are more likely to atrophy and to lose projection over time. In this group, subsequent contralateral full-thickness nipple graft, cartilage grafts have been proposed for providing secondary augmentation of the nipple. However with the advancement in technology and fillers, less invasive office procedures are now available to enhance secondary nipple augmentations. Dermal fillers have gained popularity in facial aesthetics and this can translate directly for secondary augmentation of reconstructed nipples. More permanent fillers such as Arcticoll may become popular in the first line of therapy in the future.

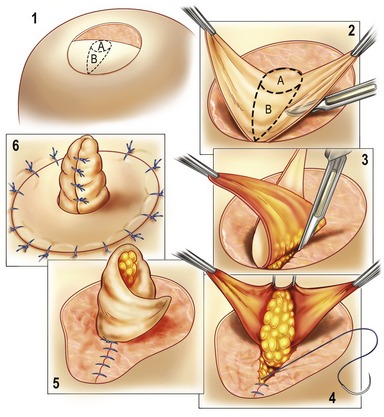

The other technique for nipple creation utilizes local flaps, the most popular of which is the skate flap technique with multiple modifications (Fig. 58.3). This flap is designed in a linear configuration radiating from the central base with large wings on each side. The base is oriented away from the mastectomy scar, and it can be oriented either transversely or vertically, with the flap oriented perpendicular to the base and extending within the planned areola site. In general, the base is oriented transversely and located either inferior or superior to the midaxis of the areola. The middle third of the base line represents the actual base of the flap and is usually 1.5 cm in width. The wings (approximately 1 cm in length) are elevated at the level of the deep dermis, and the linear portion includes deep fat. It is held at a 90 degree angle and wrapped with the wings themselves. The entire flap should be designed within the planned site of the areola to avoid visible scars outside the area of the subsequent pigmented areola. When the skate flap is designed on flap skin, less fat is required because dermis is thicker (especially on the latissimus dorsi skin island). When the skate flap is designed on a preserved breast skin envelope, the dermis is often thin, so fat down to the capsule (if there is underlying implant reconstruction) is elevated with the pedicle to ensure adequate bulk to the nipple. The two wings of the flap are now rotated 90 degrees to a position opposite the midpoint of the flap base. The distal tips of these flaps are sutured together to the midpoint of the hemi-circle. The two donor sites for the wings are closed directly. The wings are then approximated to form a nipple tube. The end of the tube will require dog-ear modification to establish a flat plane as opposed to a pointed tip of the nipple. The bases of the wings are sutured to complete the nipple reconstruction.

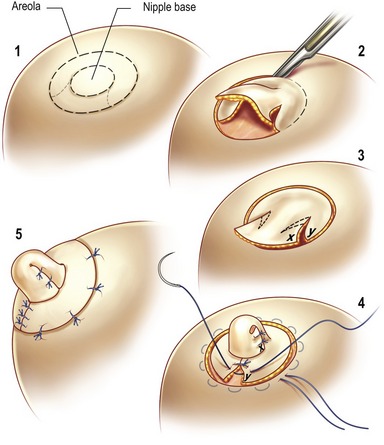

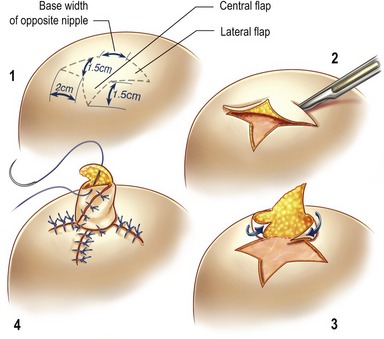

Other skate variant flaps have also been described that are similar in principle, including the cervical-visor (C-V) flap, modified star flap (Fig. 58.4), Tennessee flap (Fig. 58.5), skate-flap purse-string nipple technique and others. The advantage of these flaps is that a full thickness graft or a skin graft is not needed for the closure and the volume of the flap is dependent on the volume of the underlying tissues, limiting this procedure in patients with thin skin subcutaneous tissue or, at times, radiated tissues.

Fig. 58.4 1–4, Planning, elevation, assembly, and donor site closure of the modified star flap.

From Shestak KC, Gabriel A, Landecker A, et al. Assessment of long-term projection: a comparison of three techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;110:780.

The bell flap (Fig. 58.6) incorporated a pull-out flap that is elevated and folded on itself with primary closure of the flap donor area using a peri-areolar purse-string suture. The double opposing tab flap was devised by Kroll in the late 1980s. It is similar to the bell flap technique, consisting of an S-shaped pattern that gives it a cylindrical shape. In all these flaps the goal is to keep long-term projection therefore the nipple heights are designed 50 to 75% taller than the opposite nipple. Studies have shown that the maximum contraction occurs within the first 3–6 months and the near final height is achieved by 6 months. In a study performed by Shestak et al. (2002) analyzing the bell flap, skate flap, and star flap, the bell flap provided the least long-term projection where as the skate and its variant were considered superior in long-term projection.

Areola reconstruction

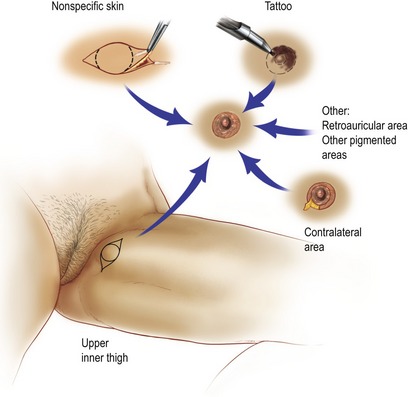

Methods for recreating the areola range from simple tattooing to the more complex grafting techniques, which are performed approximately 2 to 3 months after the nipple reconstruction. The decision as to which technique is appropriate depends on a patient’s lifestyle and preferences (Fig. 58.7). Some patients desire the quickest, painless facsimile. Therefore patient individualization is again important while taking their life responsibilities in consideration.

The simplest procedure is tattooing which has become increasingly popular. Intradermal pigmentation placed by traditional tattoo methods and equipment can be used for nipple coloration, for areolar adjustments and coloration over previously placed grafts, or for areola creation directly on the breast mound without using a grafting technique. The disadvantage of tattooing alone is that the texture and projection are often lacking even tough acceptable color match is obtained. The initial tattoo must be darker than the desired final color because the result will fade with time. This phenomenon is related to the quantity of blood that is resorbed during the procedure associated with the ingestion of the pigments by the macrophages. Some patients may present with redness after the procedure associated with an edema and an itching sensation that remains for a few hours. Fading of the pigments is common; however, fading may be revised with touch-ups in approximately 3 months.

Complications

Summary of steps

1. The nipple–areola position is determined visually with the patient in a standing position and the shoulder relaxed without abduction.

2. Nipple–areola reconstruction is usually performed as a delayed procedure and can be either under local or general anesthesia and it is done on an outpatient basis.

3. Nipple reconstruction: When the contralateral nipple is of adequate size, a composite graft can be taken from the opposite nipple. It comes from the lower one half of the nipple or the tip, depending on its shape. This graft is sutured to the central portion of the de-epithelialized areola site and generally takes well.

4. When the opposite nipple is absent or lacks projection or the procedure is undesirable to the patient, grafting, flaps, and tattoos are the primary reconstructive choices.

5. The most popular local flap is the skate flap technique, with multiple modifications.

6. Implants may be used to reinforce or to re-establish nipple projection.

7. Areola reconstruction: Methods for recreating the areola range from simple tattooing to the more complex grafting techniques, which are performed approximately 2 to 3 months after the nipple reconstruction.

Anton M, Eskenazi L, Hartrampf CR. Nipple reconstruction with local flaps: star and wrap flaps. Perspect Plast Surg. 1991;5:67.

Broadbent TR, Woolf RM, Metz PS. Restoring the mammary areola by a skin graft from the upper inner thigh. Br J Plast Surg. 1977;30:220.

Eng JS. Bell flap nipple reconstruction: a new wrinkle. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;36:485.

Gruber RP. Nipple–areola reconstruction: a review of techniques. Clin Plast Surg. 1979;6:71.

Hallock GG. Polyurethane nipple prosthesis. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;24:80.

Hartrampf CR. Nipple–areola reconstruction. In: Hartrampf CR, ed. Breast reconstruction with living tissue. Norfolk, VA: Hampton Press; 1991:32–45.

Jones G, Bostwick J, III. Nipple–areola reconstruction. Operative Techniques Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;1:35.

Kroll SS. Nipple reconstruction with the double-opposing-tab flap. Plast Surg Forum. 1987;10:219.

Masser MR, Di Meo L, Hobby JA. Tattooing in reconstruction of the nipple and areola: a new method. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84:677.

Shestak KC, Gabriel A, Landecker A, et al. Assessment of long-term projection: a comparison of three techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:780.

Spear SL, Little JW, Convit R. Intradermal tattoo as an adjunct to nipple–areola reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:907.

Ullmann Y, Pelled LJ, Laufer D, Blumenfeld L. Nipple–areola reconstruction with a custom-made silicone ectoprosthesis. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;28:485.