Nevus and Melanoma

Terminology and Classification of Skin Lesions

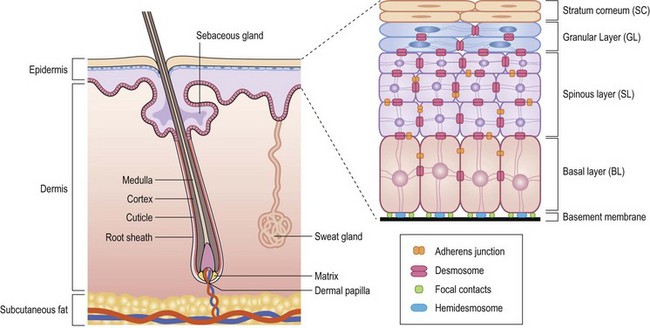

The terminology used for pigmented and nonpigmented cutaneous lesions is often confusing with multiple designations. The correct dermatologic terms are essential for clear communication (Table 71-1). An understanding of the epithelial embryology, anatomy, and physiology is also important for the clinical identification and correct classification of these lesions. As a reference, Figures 71-1 and 71-2 depict the basic anatomy of the dermis and epidermis.

TABLE 71-1

| Term | Definition |

| Nevus | Proliferation of cells within their tissue of origin |

| Macule | Circumscribed, pigmented lesion, less than 5 mm in diameter without elevation or depression from the surrounding skin |

| Patch | Lesion with larger area of involvement without palpable characteristics |

| Papules | Solid elevated lesions less than 5 mm in diameter and plaques are raised lesions larger than 5 mm |

| Nodules | Lesions that arise from the dermis or subcutaneous tissues |

| Dermal melanoses | Pigmented lesions resulting from the deposit of melanin in melanophages, free melanin in the dermis or in dermal melanocytes |

| Melanocytosis | Lesion associated with increased number of melanocytes |

FIGURE 71-1 Structural organization of the epidermis and dermis. (Redrawn from Fuchs E, Raghavan S. Getting under the skin of epidermal morphogenesis. Nat Rev Genet 2002;3:199–209.)

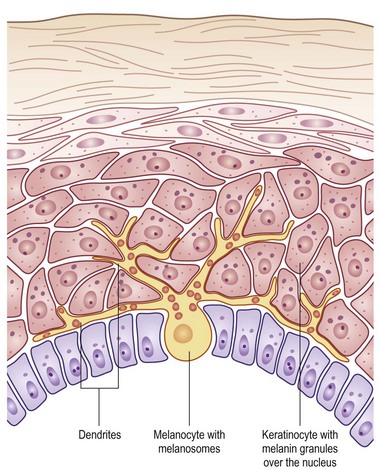

FIGURE 71-2 The melanocyte rests within the basal layer of the epidermis and is associated with a group of keratinocytes to which it delivers the melanosomes. (Redrawn from Gray J. The World of Skin Care. Available at http://www.pg.com/science/skincare/Skin_tws_16.htm.)

Anatomy of the Dermis and Epidermis

The skin is a morphologically and functionally complex tissue providing protection against physical elements by its anatomic structure and potential for immune responsiveness. The outermost layer is the stratum corneum or horny layer, which is composed of devitalized keratinocytes (see Fig 71-1). While the dermal layer is a derivative of the paraxial mesoderm, embryologically the epidermis is of ectodermal origin.

The basal layer of the epidermis is the site of mitotic activity leading to the proliferation of keratinocytes. This basal layer consists of columnar cells anchored to the basement membrane via hemidesmosomes and anchored to the dermis via penetrating fibrils (see Fig. 71-1). Interspersed between the basal cells reside melanocytes that are dendritic cells and are the source of melanin (see Fig. 71-2). Melanocytes are not secured via desmosomes or tonofilaments. Functional units (epidermal melanin units) are composed of a melanocyte and the keratinocytes to which it is responsible for the transfer of melanin. Melanosomes are the cytoplasmic organelles that result from the fusion of vesicles containing tyrosinase and vesicles containing the structural melanosomal proteins, both of which are generated by the melanocyte’s endoplasmic reticulum. Differential skin pigmentation amongst individuals results from the variable production of melanosomes, their content and rate of degradation, and not on numbers of melanocytes. The absence of tyrosinase prevents formation of melanosomes and results in albinism. The melanosomes migrate from the perinuclear area along microtubules to the dendritic tips where these are phagocytized by the keratinocyte. As the squamous cells differentiate, the melanosomes are degraded by lysosomal enzymes.

Classification of Nevi

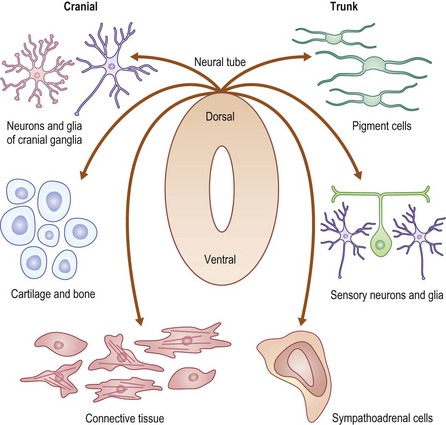

The most definitive classification is according to the cell of origin, and results in stratification between melanocytic and nonmelanocytic lesions. The melanocyte is a dendritic cell and neural crest derivative (Fig. 71-3). During development, the melanocyte precursors (melanoblasts) migrate to the dermis, hair follicles, leptomeninges, uveal tract, and retina. After the eighth week of development, they migrate from the dermis to the epidermis. Melanocytic nevi are derived from melanocytes or their precursors, and distinguish themselves by virtue of (1) the absence of dendrites; (2) the clustering of cells; (3) their variable location within the dermis and epidermis; and (4) their variable content of melanin (Table 71-2).

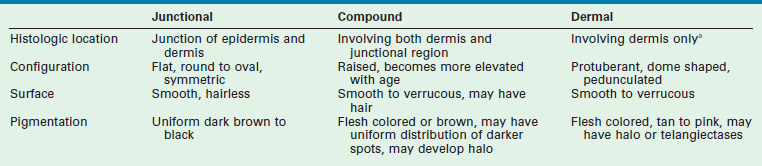

TABLE 71-2

Clinical and Histologic Features of Melanocytic Nevi

aOnly in the presence of ulceration or reticular dermal invasion.

FIGURE 71-3 The neural crest derivation of these dendritic cells explains the association of melanocytic disorders with CNS, bony, and ophthalmic disorders. (Redrawn from www.nature.com/nrg/journal/v3/n6/images/nrg819-i1.jpg.)

The principal location of the nevus in the skin serves as a second potential descriptor. In contrast to the nonmelanocytic epidermal nevus, melanocytic nevi can be situated: (1) at the junction of the epidermis/dermis (junctional); (2) involve both regions (compound); or (3) be confined to the dermis (dermal). These are generic histological terms and do not imply biologic behavior.

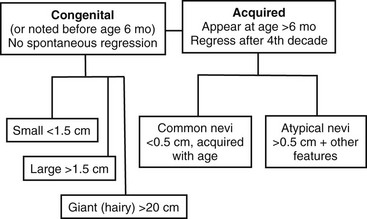

The third dimension is related to the time of appearance. Melanocytic nevi can be classified according to whether or not they involve disorders of (1) melanocyte migration or (2) proliferation. These lesions are most commonly categorized based on age at presentation as either congenital or acquired (Fig. 71-4) Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) result from failure of embryologic migration of the melanocyte precursors and form hamartomatous lesions evident at birth, which may evolve over time. In addition, congenital nevi can occasionally present after birth up to age 6 months. Failure of migration also results in a variety of dermal melanoses, some of which are encountered most frequently as the ‘Mongolian’ spot over the dorsal sacral region of infants. In contrast to the congenital nevi, acquired nevi are proliferative lesions and represent benign neoplasms of the skin that are located within the epidermis, dermis, or both. Acquired melanocytic nevi are the result of benign proliferative disorders of nevi that have a tendency to increase in number during childhood, adolescence and early adulthood, but then spontaneously regress with age. Based on more specific clinical characteristics, including total numbers of lesions, family history, and specific appearance, subsets of nevi can be identified that will have unique risks related to melanoma.

Nonmelanocytic Nevi

Epidermal nevi are skin lesions not associated with proliferation of melanocytes. Instead, these represent proliferations of ectodermal origin that are classified based on their hyperplastic element. Keratinocytic lesions involve the epidermal layer only, whereas the organoid lesions involve the sebaceous, apocrine, eccrine, and follicular structures. These epidermal nevi are clinically distinct and appear as raised, pigmented, velvety to wart-like proliferations of the dermis along dermatomal distributions. Lesions are usually apparent in infancy, but some may appear in later childhood. The incidence in newborns is less than 1%. The most common sites involved are the scalp, face, trunk, and proximal extremities. Often a hairless patch is noted on the scalp or a raised linear yellow-tan to orange plaque is evident on the face or trunk during infancy. With age and the hormonal changes during puberty, these lesions change in appearance and become verrucous or develop more coarse hair growth. These progressive changes are what initiate the request for excision, along with the concern for potential malignant degeneration after puberty.

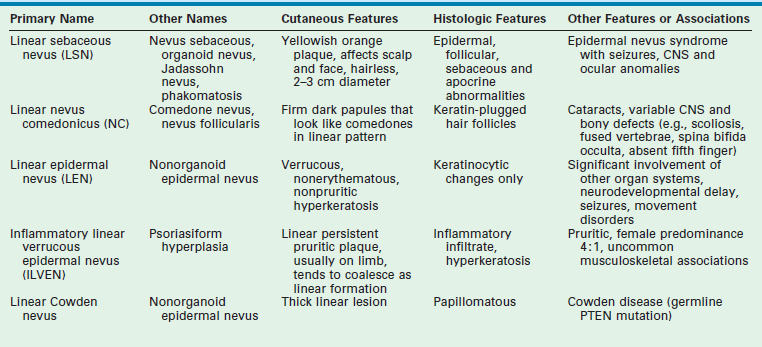

A number of syndromes are associated with these epidermal nevi, particularly when they are large or extensive. The epidermal nevus syndromes typically involve abnormalities of the central nervous system (CNS), ocular system, and skeletal system. While the classification of these lesions and syndromes is based on clinical findings, advances in molecular biology suggest that these disorders are based on genomic mosaicism and future biologic classification will become possible.1 The common variants of epidermal nevi include the (1) nevus sebaceous (Fig. 71-5) that represent 50% of the epidermal nevi; (2)keratinocytic nevi; (3) nevus comedonicus (Fig. 71-6); (4), inflammatory linear verrucous nevus; (5) linear Cowden nevus; and (6) Becker’s nevus (pigmented hairy epidermal nevus). Table 71-3 summarizes their clinical and histological features.

FIGURE 71-5 This young child has the classic appearance of a nevus sebaceous, which is a solitary yellow-orange plaque on the scalp. These lesions are well circumscribed, hairless, oval to round, and usually less than 2–3 cm in diameter.

FIGURE 71-6 In the right axilla of this 5-year-old is a nevus comedonicus (arrow). This lesion is a well-circumscribed plaque that is composed of keratin-plugged hair follicles. It was present at birth and has been slowly enlarging.

These lesions are associated with a risk for transformation. The most common association is between nevus sebaceous and basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and this risk of transformation is believed to be based on shared deletions within the PTCH tumor suppressor gene. This natural history has formed the basis for current recommendations for excision prior to adolescence. A recent review by Rosen et al. suggests that the incidence of carcinoma may be less than previously reported as the demographic features of prior reports focused on predominantly adult populations.2 In this study, the mean age was 7.2 years (range 0.3–54 years). Six hundred fifty-one epidermal lesions in 631 patients were evaluated for the presence of a second intralesional diagnosis. Five patients had BCC (0.8%) and 1.1% had syringocystadenoma papilliferum. The mean age of BCC diagnosis was 12.5 years (range 9.7–17.4 years). On the basis of this finding of occasional prepubertal malignant degeneration, the authors advise individual counseling with patients and their families, informing them of the extent of resection and reconstruction techniques that may be required. The scalp pliability of the young child may also offer advantages and opportunities that must be taken into consideration when cosmetic concerns outweigh the concerns for malignant transformation. Certainly there is no scientific basis for suggesting an intervention to avoid malignant degeneration in infancy and early childhood.

Melanocytic Nevi

Congenital Nevi

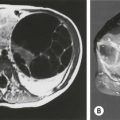

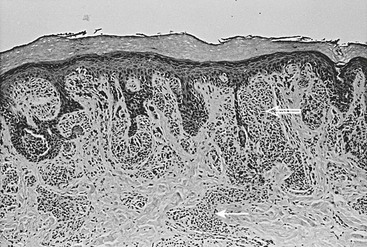

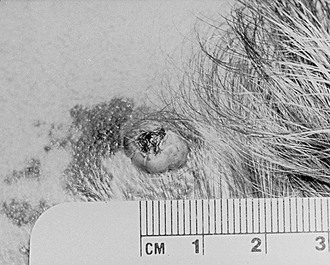

CMN are pigmented lesions of variable size that develop during the first few months of life. They are the consequence of failure of melanocytic migration into the epidermis. These lesions grow proportionally with the infant and are generally categorized as small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5–20 cm), and large (>20 cm). Those especially large lesions (>40 cm) are also referred to as a garment nevus, giant hairy nevus, or bathing trunk nevus since they tend to cover large truncal areas in confluence (Fig. 71-7). Although the pigmentation and surface are initially uniform and flat, the lesions evolve into thick, dark, and often hair-covered lesions. Histologically, the melanocytic cells in congenital nevi are located deeper than in acquired nevi (Fig. 71-8). The absence of superficial involvement may explain why transformation is often not noticed until late in its development. The incidence of transformation is greatest in the large or giant congenital nevi, and low in small to medium size lesions. The size of the congenital nevus therefore becomes the key element in discussing management.

FIGURE 71-7 Giant congenital melanocytic nevus (garment nevus) of the back and buttock in a neonate.

FIGURE 71-8 Congenital melanocytic nevus is characterized by nevus cells extending from the dermal–epidermal junction (open arrow) along skin appendage structures into the deep dermis (solid arrow).

The management of large or giant CMN is more controversial. The melanoma risk for these lesions is increased and estimated to be 5–10% over a lifetime with 50% of this risk during the first five years of life.3,4 The highest risk lesions are associated with the nevus that is situated over the posterior trunk, greater than 40 cm in maximal dimension, and associated with satellite nevi. Melanoma in these patients can arise from the deep dermal layer or even originate from sites distant from the skin such as the CNS (2.3% in one study5) or retroperitoneum.4 These patients are also at risk for neurocutaneous melanosis (7% in one study5) and CNS malformations such as Dandy–Walker malformation, defects of the vertebra, skull, and intraspinal lipomas. Screening MRI of the brain and spinal cord is recommended during first six months of life in these patients.5 Conversely, two-thirds of patients with neurocutaneous melanosis have giant CMN and the others have multiple nongiant lesions. The prognosis for patients with symptomatic neurocutaneous melanosis is extremely poor even in the absence of malignancy.6 The increased routine surveillance with MRI during infancy for children with large CMN has identified those with asymptomatic CNS involvement, and hopefully will impact the care and outcome of these patients in a positive manner. These patients are also at risk for other soft tissue malignancies such as rhabdomyosarcoma7 or neurofibrosarcoma (peripheral nerve sheath tumor).

Since operative resection of these extensive lesions is often not feasible and never completely eliminates the risk for melanoma, these patients need close medical surveillance. Areas of epidermal change within the nevus should be biopsied. However, caution must be exercised in interpreting the histological results, since the proliferative nodules may resemble melanoma, but behave in a benign manner.8 Features useful in differentiating a cellular nodule from melanoma include: (1) lack of high grade uniform cellular atypia; (2) lack of necrosis within the nodule; (3) rarity of mitoses: (4) evidence of maturation; (5) lack of pagetoid spread; and (6) no destructive expansile growth.9

When operative intervention is needed, collaboration with colleagues with added expertise in the use of tissue expanders, rotational flaps, and skin grafting may be helpful. In one study, the mean age for intervention was 5.1 years and took an average 1.3 years to complete resection and reconstruction in these patients with large and giant CMN.10 While the authors expressed a preference for earlier intervention, they acknowledged that the average age of the patients referred to them was 4.7 years, and many had already undergone an operative procedure. Over half of the cohort required more than one operative intervention and 22 of 40 patients needed skin grafts. Also, 18 patients benefitted from tissue expanders and autologous cultured skin replacements.

Acquired Nevi

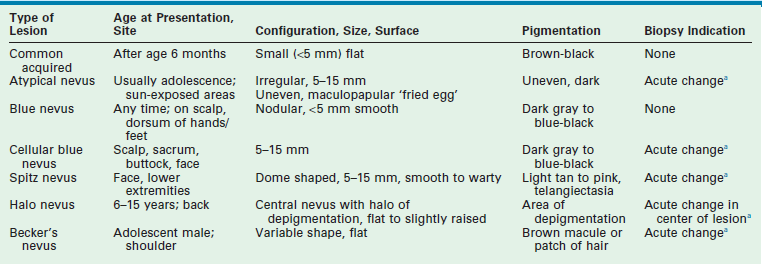

Histologically, these acquired melanocytic nevi are divided into subtypes based on the location of the nests of nevus cells, and this feature corresponds with certain clinical findings (see Table 71-2). Junctional nevi tend to be flat with brown/black pigmentation and the nevus cells are located at the dermal–epidermal junction. When the nevus cells extend from the junction into the dermis, the lesion is described as a compound nevus. Clinically, this corresponds to a lesion that is slightly raised and pigmented brown/black. When the nevus cells migrate completely into the dermis, the lesion is an intradermal nevus, which is raised and typically not pigmented. In general, the deeper the nests of nevus cells, the more raised and less pigmented the lesion. (i.e., dark flat lesions vs raised tan lesions). The temporal evolutionary path of nevi was originally described by Stegmaier and explains the clinical observations of progressive change within individual nevi or their resolution.11 Newer nevi tend to be small and flat (junctional), and either develop a raised profile or disappear with time as a consequence of fibrosis. In one study, when the nevi on adolescents were followed over a 4-year period, there was a net increase of 50% in total number of nevi, despite a complete regression in 15%.12 This demonstrates the potential for active turnover in individual patients. Freckling and lighter colored skin are associated with increased numbers of nevi. In darker skinned individuals, nevi also develop, but are usually found on the palms and soles, unlike in the more fair complexioned individuals.

Sun exposure during childhood, especially when it is intense, intermittent, and not necessarily associated with sunburn, is a promoter for nevus development, and is the major environmental factor associated with the risk of melanoma. Recent evidence suggests that sunscreen use has led to a false sense of security in that it provides incomplete protection to UV rays.13 Sunscreen alone does not provide sufficient protection. Public health education must focus on the avoidance of midday sun and the use of physical barriers such as UV protectant clothing and hats.13–16

The role for excision of these acquired nevi is limited when they are clearly defined by their age at presentation and the features described in Table 71-2. The natural evolution and changes in these common lesions should not be mistaken for malignant progression.

Atypical Nevi

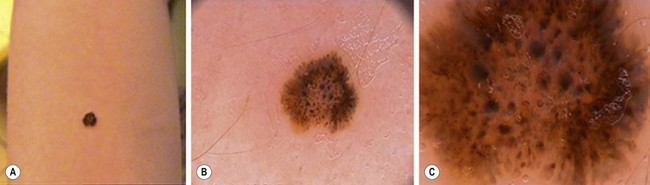

Atypical nevi, previously referred to as dysplastic nevi or Clark’s nevi, are common lesions found in 5% of the population, and may occur either sporadically or in a familial pattern (Fig. 71-9). The onset of their first appearance is usually during adolescence on the sun-exposed areas of skin, and they continue to increase in number and size with age. Unlike the common acquired nevi, these lesions are usually larger than 5 mm (up to 15 mm), and have an irregular surface ranging from completely flat to flat with a raised center resembling a fried egg. The pigmentation usually is dark and irregular, and the border of the lesion is often irregular as well. These lesions are most common in persons with light skin and hair color. Ultraviolet light has been implicated in the transformation of melanocytes in these nevi.

When a patient has multiple atypical nevi or moles, they may be diagnosed with the atypical mole syndrome. While it can be normal to have up to 10 to 20 nevi, people with this syndrome may have in excess of 100 moles. Individuals with 50–100 nevi and one or more first- or second-degree relatives with melanoma are considered to have the familial atypical mole and melanoma (FAMM) syndrome that identifies them at significantly increased risk (approaching 100%) for the development of melanoma. It is important to note that the melanoma may arise de novo on any part of the body and not necessarily from a preexisting atypical lesion. Simple excision of an atypical nevus therefore does not obviate the patient from close dermatologic follow-up. In families with the FAMM syndrome, nevi arising on the scalp can be an early predictor for this syndrome, although the scalp nevus itself may involute with time. In these individuals, the nevi tend to be similar in appearance, the corollary being that a new nevus that varies in appearance or location should be regarded with suspicion. The ability of clinical health care providers as well as nonclinicians to identify the ‘ugly duckling’ has been found to be reliable.17 Routine surveillance examinations with photo documentation are recommended with dermoscopic (epiluminescence microscopy) evaluation of those nevi undergoing significant change. Dermoscopy has been shown to improve sensitivity and specificity with regard to detecting melanoma.18

Specific Congenital or Acquired Melanocytic Lesions Requiring Distinction from Melanoma

Several melanocytic nevi are discussed separately due to their unique features, which frequently prompt their evaluation for malignancy. These lesions can be congenital or acquired, and are described in terms of their junctional, compound, or dermal location (Table 71-4). A recent review by Schaffer provides some practical advice regarding these specific lesions.13

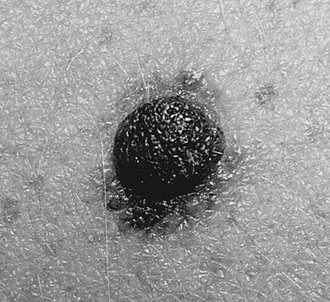

Halo nevi (Sutton’s nevi) are unique lesions which appear between 6–15 years of age, and are typically located on the trunk or extremities. They appear as round or oval lesions, with a central area of pigmentation that may be tan to brown in color, and are surrounded by a rim of depigmentation (Fig. 71-10). Histologically, the central nevus is usually a compound or dermal nevus surrounded by a uniform infiltrate of T-lymphocytes. Pigmentation can be intermittent. Excision is limited to those that develop atypical characteristics within the pigmented part. There is no association with malignancy. These nevi cause clinical suspicion only because regressing melanoma may be gray or white.

FIGURE 71-10 The classic appearance of a halo nevus. These small pigmented lesions are surrounded by a rim of hypopigmentation. They are typically seen in adolescents and are most commonly located over the trunk, especially on the back. Treatment is usually not needed unless the pigmented portion of the halo nevus appears atypical. In that case, excision of the entire lesion, including the halo, is recommended.

A blue nevus is a benign proliferation of dendritic dermal melanocytes. Its etiology is attributed to a dermal arrest in embryonic migration of neural crest melanocytes that fail to reach the epidermis and thus create a hamartoma. This is a lesion with a large amount of pigment within the dermis, resulting in absorption of longer wavelengths of light and scattering of blue light known as the Tyndall effect. Two variants of blue nevi are distinguished based on their size: (1) the common blue nevus is usually less than 5 mm; and (2) the cellular blue nevus measures 1–3 cm.

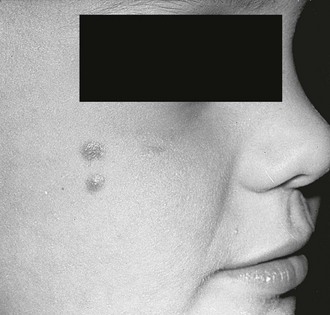

Spitz nevi are raised, often light or nonpigmented lesions (light tan-red or reddish-brown) that appear dome-shaped with either a smooth or a verrucous surface (Fig. 71-11). Histologically, these lesions are compound nevi, although pure junctional and pure dermal variants exist as well. Dermatoscopic examination shows a starburst pattern (Fig. 71-12). These lesions tend to occur on the face or lower extremities, and measure 0.3–1.5 cm in diameter. There is a slight female preponderance with 50% of these occurring in children under 10 years of age and 70% under 20 years of age. The increased red coloration is due in part to increased vascularity, with telangiectasia in the superficial dermis. The vascular surface features explain why these lesions are more prone to bleeding with minimal trauma.

FIGURE 71-12 This patient has a Spitz nevus on her arm. Dermatoscopic examination shows a classic starburst pattern. (Photographs courtesy of Dr. Eric Ehrsam. Reprinted with permission.)

The pigmented variant of the Spitz nevus is known as a nevus of Reed, and typically occurs on the leg of a young woman. The appearance of Spitz nevi may be quite sudden, prompting the concern for potential melanoma. Spitz nevi were previously classified as ‘benign juvenile melanoma,’ a misnomer which was responsible for the misconception that pediatric melanoma was less aggressive than the adult melanoma counterpart. Most Spitz nevi are completely benign; however, atypical clinical features such as a diameter greater than 1 cm, asymmetry, or ulceration should prompt complete excision. Most often, a young patient who has undergone a shave biopsy is referred for complete excision of the lesion so that it may be fully evaluated by a dermatopathologist. One must remember that one pitfall of a shave biopsy is that the most atypical portion of the lesion is examined and may incorrectly reflect the overall nature of the lesion. There is a spectrum of lesions from the benign Spitz nevus to the spitzoid melanoma. Those intermediate lesions with atypical histologic features have become the center of much controversy, and are often referred to as melanocytic or spitzoid tumor of uncertain malignant potential.

In approximately 10% of all cases, histological features within these lesions do not permit distinction between a Spitz nevus and a spitzoid melanoma. These atypical Spitz nevi then become diagnostic and treatment dilemmas. In these complicated instances, one might consider the safest approach would be to treat the lesion as a melanoma equivalent of the same depth. Berk et al. have reviewed the Stanford experience regarding these lesions.19 Although some surgeons have advocated for sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) as a supplemental tool for categorizing the histologically indeterminate lesion, this approach has been strongly criticized as being unnecessarily invasive for the limited information gained. In the limited numbers of patients who underwent SLNB and were then treated with completion lymph node dissection (CLND) and chemotherapy, there was no disease recurrence.20 Also, the current biologic and clinical evidence indicates that the presence of melanocytic lymphoid infiltrate does not predict clinical behavior, and may not even identify metastases or even malignancy as it does for melanoma.21

Several authors have recently reported their experience in the management of these confounding lesions. In a meta-analysis of 10 recently published series, 175 patients underwent SLNB and 67 were found to have positive SLN status (38%).22 However, this relatively high incidence of SLN positivity does not provide the prognostic information that it does for adult melanoma, and seriously questions the overall utility of SLNB. This is further emphasized by Ghazi et al., who found that on a median follow-up of 56 months, 90% of their patients are free of recurrence.23 They suggest that therapeutic SLND should be limited to those patients with clinically palpable nodes, and patients who have positive SLN should simply be monitored with ultrasound (US) for recurrence or progression rather than being subjected to CLND. Another group reported on their patients treated without SLNB. Twenty-nine patients underwent resection of the primary lesion, and with a mean follow-up of 8.4 years (range 3.5–15.8 years), 14 had no recurrence.24 An additional 10 patients had a shorter duration of follow-up (mean 2.8 years), and had no evidence of recurrence. Their recommendation for these atypical spitzoid tumors is excision with clear margins and careful clinical follow-up.

The nevus of Ito and nevus of Ota are congenital dermal melanocytic disorders that develop because of incomplete migration of melanocytes resulting in a hamartomatous lesion. These lesions are most commonly found in Asian populations. In the case of the nevus of Ota, the lesion appears along the distribution of the ophthalmic and maxillary branches of the trigeminal nerve on the face, and is evident as a blue-gray patch. These nevi may also involve the ocular and mucosal surfaces. The nevus of Ito involves pigmentation over the shoulder area and is often associated with a nevus of Ota. The pigmentation becomes more prominent with age and may be amenable to laser therapy.25 Melanoma has been reported to arise infrequently in the nevus of Ota, but the association with glaucoma is important and should lead to ophthalmologic referral.26

Nevi Occurring at Special Sites

A number of nevi occur at sites that have been particularly concerning for melanoma. They are now referred to as ‘lesions with site-related atypia that must be distinguished from their malignant counterpart’.27 Atypical scalp nevi are a frequent cause for referral for excisional biopsy on the basis that they may be difficult to follow. They can also be markers for patients with the FAMM syndrome or dysplastic nevus syndrome. A recent observational study of 44 scalp lesions documented that they are morphologically active lesions during the childhood years, and suggested that the same principles for excision should apply as for other atypical nevi.28

Acral nevi are found on the palms and soles. Although they may exhibit linear streaks, they must be viewed with suspicion if they have mottled pigmentation and are greater than 7 mm.29 Longitudinal melanonychia are pigmented streaks emanating from the nail matrix and can be a normal variant that is most frequently seen in darker skinned individuals. Dark bands and those lesions that are wider than 6 mm, or associated with nail dystrophy, or extending beyond the nail fold, should be biopsied to exclude melanoma.30,31 On mucosal surfaces, distinction must be made between labial melanotic macules which are benign lesions on the lower lip of women that resemble freckles but do not darken with sun exposure, and more concerning lesions in the oral cavity.32 In young women presenting with melanotic lesions over the vulvar area, it is important not to overtreat these generally benign lesions.33

Pediatric Melanoma

Melanoma remains a rare cancer in childhood, with children representing less than 2% of all patients with melanoma.34 There has been a worldwide doubling in the number of melanoma cases in adults over a period of 25 years with age-standardized incidences now at 15 per 100,000/year and 22 per 100,000/year in men and women, respectively.35 Pediatric melanoma has become more prevalent, but the rate of increase is not as dramatic and primarily affects the postpubertal age group. Current estimates show an annual incidence of 0.8/million in the first decade of life. Melanoma becomes an increasingly prevalent neoplasm with age. In patients cohorted by age <15years, 15–19 years and 20–24 years, melanoma contributes to 1%, 7% and 12%, respectively, of all malignancies in each category.36 The highest rates are reported from Australia and New Zealand where melanoma affects 30/million in the 10–14 year age group.37 Regardless of geographic factors, these data are indicative of a dramatic increase in the lifetime risk of cutaneous melanoma for children born today (1/58 as compared to 1/250 in 1980).38

Fortunately, there has also been a leveling off in the mortality associated with melanoma. The identification of patients at risk has allowed for improved surveillance. This has presumably resulted in improved early detection, with 90% of new diagnoses involving thin, less than 1 mm melanomas. Some of this improvement in early diagnosis can be linked to the use of dermoscopy39 and computer-based dermoscopy in differentiating between small melanomas and atypical moles.40

The known melanoma risk factors are both environmental as well as heritable. Although melanoma is not limited to Caucasians, evidence has shown that the melanoma risk is associated with fair complexion, the presence of freckles and moles, and intermittent intense sun exposure, even in the absence of severe sunburns. While patients with large CMN are at risk early in life, those patients with the atypical mole syndrome and FAMM syndrome must undergo careful clinical surveillance at all ages. The most important factor for the development of melanoma is the presence of melanocytic nevi, with an eightfold increase in relative risk for those with greater than 100 moles.35 If a person has five or more atypical nevi, he/she has a nearly 50-fold risk of developing melanoma. If a family history of melanoma is present, the incidence approaches 100%. Recent studies based on genetic analysis of families with mutations in the melanoma predisposition gene CDKN2A suggest that the FAMM syndrome has a 70% lifetime penetrance of melanoma with sun exposure. Mutations in the melanocortin-1 receptor further impact the development of melanoma.41,42

It is critical to understand that most (80%) lesions arise de novo and not from preexisting lesions. For example, in a series of 33 prepubertal patients with melanoma, seven cases arose from nongiant CMN, two from an acquired nevus, and 24 (73%) de novo.34 Whereas genetic factors and pigment traits contribute to the development of nevi, the only controllable factor for melanoma is the cumulative environmental effects of sun exposure. These sun factors are best limited with physical barriers such as clothing and hats, and avoidance of the midday sun. The use of sunscreen appears to be principally effective in preventing sunburn. Blistering sunburns during childhood and adolescence have been implicated in the development of melanoma.15

The demographics of pediatric cutaneous melanoma are well described in an extensive review that compares their experience with 137 patients to other published series.43 The authors found that gender neither predisposed nor conferred a measurable survival advantage for melanoma. As noted earlier, the incidence escalates with age and the relevant cutoff appears to be the transition between prepubertal and pubertal patients, which normative data suggests is around 10 years of age. Postpubertal patients have a higher mortality from melanoma. The rate in 15–19-year-olds is estimated to be eight- to 18-fold higher when compared to their younger counterparts. Site of involvement is variably reported as extremities > trunk > head and neck. It is not clear that this has prognostic implications, except that head and neck lesions are perhaps more difficult to treat, which has given them the reputation for a less favorable prognosis.

The extent of disease is localized in most pediatric patients (>80%), while 10–15% may have nodal involvement, and 1–3% will present with metastases to distant sites including lung, liver, LN, subcutaneous tissues, and brain.44

Specific Predisposing Conditions for Pediatric Melanoma

The diagnosis of melanoma is made in children in several discrete clinical contexts. Congenital melanoma is the least common, and is associated with transplacental transmission. It also may arise from a primary cutaneous lesion. The appearance of any rapidly growing, ulcerating, or bleeding lesion in the newborn should be evaluated promptly. However, the incidence of this clinical scenario is so low that projections about outcome are difficult to estimate, but the prognosis is generally poor. Confounding variables include reports of spontaneous regression and the presence of micrometastases that do not appear to correlate with survival.8,45

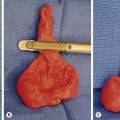

Melanoma associated with CMN has been well described and presents a unique set of clinical issues (Fig. 71-13). The lifetime risk for development of melanoma in patients with CMN is variably estimated between 5–40%.46 More conservative estimates indicate a 5–10% lifetime risk, with half of this risk distributed within the first five years of life.3,47 Two recent prospective studies of patients with giant CMN showed the incidence of melanoma during the first five years of life was between 3.3–4.5%.48,49 Those patients with a posterior axial location and numerous satellite lesions have the greatest risk as compared to those with lesions restricted to the head and extremities.13

FIGURE 71-13 Congenital melanocytic nevus of the scalp with a melanoma arising from it (raised centrally pigmented lesion).

These tumors may originate from deep dermal sites and are often not visually apparent. Despite the sometimes ominous appearance of the satellite lesions, these have not been documented as the primary site for melanoma. Proliferative nodules within giant CMN often raise the specter of malignancy, but numerous authors caution against hasty conclusions in this clinical scenario.8,50 Neurocutaneous melanosis occurs in conjunction with large CMN and is the most common cause for nonepithelial melanoma. Although techniques for resection and reconstruction have improved such that disfigurement can often be avoided, these remain challenging operations. Moreover, there is no assurance in alleviating this risk for nonepithelial melanoma despite full-thickness removal of the CMN. In contrast, the smallest (less than 1.5 cm) CMN lesions are not associated with any increased risk for melanoma. It is within the intermediate group that little data exist to help guide management. At Massachusetts General Hospital, CMN lesions up to 5 cm have not been associated with melanoma in patients under 20 years of age.46 Illig et al. reported melanoma arising in CMN lesions less than 10 cm only after 18 years of age.51 Rhodes and Melski calculated a lifetime risk of 2.5–5.0% in persons with small CMN living to 60 years of age.52

While large and perhaps some intermediate-sized CMN help identify patients at risk for the development of melanoma, radical excisional therapy can be tempered by the recognition that cautious observation and selective biopsy can be an alternative therapy, especially since the melanoma can arise from sites other than the CMN. When resection is considered, preoperative planning allows for the optimal use of reconstructive techniques including skin and tissue expanders and a variety of rotational flaps or free tissue transfers in addition to skin grafts.

Other conditions predisposing to melanoma include patients with xeroderma pigmentosum in whom the inability to repair UV induced DNA damage results in a 2000-fold increased risk of skin cancer.53 Patients with genetic immunodeficiency syndromes are reported to have a three- to sixfold increased risk.54 Children on chemotherapy for childhood malignancies or children undergoing solid organ transplantation experience an increase in total nevi counts as well as the induction of atypical nevi.55 Although neonatal phototherapy for hyperbilirubinemia has been demonstrated to induce an increased number of nevi, it is uncertain whether this will escalate the risk for future melanoma.56 Unfortunately, it is important to remember that 60–80% of malignant melanoma in patients under 20 years of age occurs in the absence of known cutaneous risk factors.54

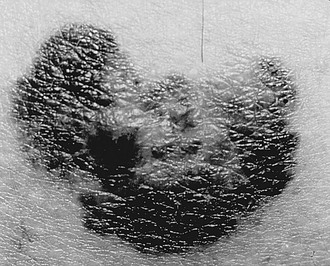

Diagnosis

The difficulty in making the diagnosis of melanoma during childhood relates to a number of variables. The natural evolution of congenital and acquired nevi during childhood and adolescence often limits the effectiveness of adult data. Also, there is limited value to the mnemonic ABCDE (asymmetry, border irregularity, color variegation, lesion diameter greater than 6 mm and evolution) (Fig. 71-14) for a pigmented lesion since variegations and irregular shape are frequently associated with an atypical nevus. Specifically, the physical characteristics of giant CMN that predispose to melanoma arise in the deep dermal layers and extend within the deep subcutaneous tissues, rather than becoming apparent externally. Consequently, childhood melanoma may present in a markedly different manner from its adult counterpart. Recent growth, ulceration, or bleeding may be the most frequent presenting features. In contrast to the adult experience with thin (less than 1 mm) melanomas, pediatric melanomas are typically greater than 1.5 mm in thickness. This may be due to delays in diagnosis, a deeper origin within a CMN, and a higher incidence of nodular melanomas in children.38 In one series of melanoma in children, the most common presenting symptoms were recent growth, pain, ulceration, itching, bleeding, and change in color in the lesion.57 In the 13 patients, three had lesions that resembled pyogenic granuloma. Only one patient presented with evidence of metastatic disease. Eleven of 13 were nodular and only two were superficial spreading. The mean tumor thickness was 3.2 mm in this series.

FIGURE 71-14 This malignant melanoma demonstrates some of the classic ABCD features for melanoma: asymmetry, border irregularity, color variegation, and diameter greater than 6 mm.

In a series in children under age 12 years, the clinical parameters that favored melanoma were a rapid increase in size (55% of patients), bleeding (35%), or color change (23%) of a nodular lesion.54 Less frequent signs or symptoms included a subcutaneous mass (6%), pruritis (15%), and enlargement of a regional LN (7%). In 7% of the patients where a melanoma developed in association with a preexisting nevus, the patients had no clinical symptoms.

A study of 33 prepubertal patients attempted to delineate the clinical features and outcomes of pediatric melanoma.34 In this series, the sites of origin were most frequently the extremity (n = 15), trunk (n = 10), and head or neck (n = 8). Interestingly, 14 of 28 patients had amelanotic lesions and the majority of lesions were raised and resembled pyogenic granuloma.34 Superficial spreading (n = 15) and the nodular melanoma subtypes (n = 9) were the most common lesions. The median lesional thickness was 2.5 mm.

The roles of clinical dermatoscopy, computer dermatoscopy (digital epiluminesence microscopy), and ultrasound imaging of the skin have been described for monitoring high risk adult patients.39,58–60 However, there are no current reports focusing on children.

Surgical Management of the Lesion Suspected to be Melanoma

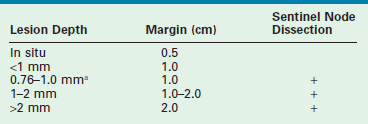

In these instances, most young children benefit from an excision under general anesthesia which allows the surgeon to focus on a full-thickness biopsy with an adequate margin. When the lesion is being excised for the first time or re-excised for atypia, it is reasonable to target a 1–2 mm circumferential margin. However, there are no prospective data to provide evidence-based recommendations. In the setting of dysplastic changes or frank malignancy, the parameters set forth by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) for melanoma should guide the resection based on the Breslow stage and Clark’s level (Table 71-5). A shave biopsy of such a lesion may not provide sufficient data and excision with an adequate 1–2 cm margin is recommended. It is in these settings that a discussion must be held with the family regarding the option for proceeding with SLNB under the same anesthetic, if appropriate.

TABLE 71-5

American Joint Committee on Cancer Guidelines for Surgical Management of Melanoma

aOnly in the presence of ulceration or reticular dermal invasion.

In the presence of established malignancy, a re-excision with margins may be needed. In the more common scenario of the histologic diagnosis of an atypical nevus with dysplasia, the likelihood of malignant degeneration is low, and a conservative re-excision is advised. This topic is most controversial in the context of Spitz nevi with cellular atypia. While most Spitz nevi can be histologically identified as benign lesions, many show atypical features that complicate their differentiation from melanoma. One set of authors have offered a well-designed proposal for the evaluation of pediatric patients with spitzoid melanocytic tumors where there is diagnostic controversy.61 A recent publication affirms that SLNB, when applied to atypical melanocytic neoplasms, shows a 30% (seven of 24 patients) incidence of positivity in the absence of further LN involvement on CLND and no progression of disease.62 While SLNB has been proposed as a means for differentiation between a benign and malignant lesion, it has limited effectiveness since the presence of melanocytic cells within a sentinel lymph node does not necessarily indicate the presence of a metastasis. The features of the melanocytic cell and its location within the lymph node may indicate that these are benign nodal melanocytes that arrived at draining nodes by lymphatic migration or formed in the nodes during development. However, even the presence of ‘metastatic’ cells in the sentinel lymph node does not appear to have the same biologic effect as they would in melanoma as the frequency of recurrent disease is virtually absent in the scenario of Spitz nevi with cellular atypia.

The collective experience from cancer centers offering SNLB for spitzoid melanocytic tumors have shown that the rates of ‘positive nodes’ range from 29–50%. A recent review indicated that 78% of the patients (n = 205) underwent SLNB and that 62 (39%) were found to have micrometastases, which then prompted >90% of these patients to undergo CLND with only 10% having additional positive nodes.20 There have been no reported deaths of LN positive pediatric patients with primary Spitz tumors.

If controversy persists, then fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or comparative genomic hybridization should be performed, and may lead to results that favor either a nevus or a melanoma.63–66 At the same time, it is important to remember the lack of correlation with survival for indeterminate melanocytic lesions based on SLNB. There will always be a few cases where the long-term follow-up will be the most important concern, recalling that nodal melanocytes may not resolve the question for the family. The best clinical course is to avoid the trap to perform SLNB or falsely offer it as a clinical advantage in these difficult cases. In the absence of a clinical trial, the therapeutic role of SLNB in this population of patients with atypical spitzoid tumors is debatable.67

Management of Histologically Confirmed Melanoma

Staging and treatment protocols of histologically confirmed melanoma are derived from the adult literature. The recommendations for extent of re-excision are based on the thickness of the tumor and generally requires a 0.5 cm margin for in situ lesions, a margin of 1 cm for lesions up to 2 mm, and 2 cm margins for lesions greater than 2 mm in thickness. SLNB is advised for lesions thicker than 1mm or those between 0.76 mm and 1 mm with ulceration or reticular dermal invasion (see Table 71-5). The new AJCC staging system is primarily based on: (1) Breslow tumor thickness with 1 mm, 2 mm and 4 mm indicating the current cutoffs for thin, intermediate, and thick lesions; and (2) histological features such as ulceration which is perhaps most important in the intermediate thickness group. Clarke’s levels are only taken into account in thin melanomas. Lymph node involvement is stratified by the number of nodes involved, and whether microscopic or macroscopic metastases are present. Finally, three subgroups of distant metastases are distinguished: (1) skin and soft tissue; (2) lung; (3) other visceral organs. Patients with visceral metastases have the worst prognosis. In this new classification, the serum LDH is used to further stratify risk. If elevation of the LDH is verified in the presence of either skin, soft tissue, or lung metastases, the prognosis is equivalent to that in patients with visceral metastases.68

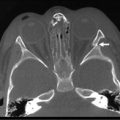

The standard imaging techniques used to identify potential metastatic disease sites include computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography (PET). PET-CT has been approved for this use as it has been demonstrated to be particularly helpful in identifying developing metastases.69 The limitations in PET scanning continue to relate to the size of the lesion, such that it cannot compete with lymph node biopsy for nonpalpable lymph nodes.70

The Role of SLNB

In adult melanoma therapy, SLNB has become a mandatory procedure in the current AJCC staging system to detect lymph node micrometastases. With a positive SLNB, the recommendation is to proceed with a CLND. A negative SLNB, however, does not guarantee lack of distant spread. It is evident that this algorithm protects against early locoregional recurrences, but does not have an impact on overall survival. These protocols have been applied to pediatric patients with melanoma and atypical melanocytic tumors. In one review, 20 patients under 21 years of age underwent SLNB for melanoma or atypical nevi.71 No complications occurred as a result of the SLNB, and results showed that positivity correlated with tumor thickness. Five of 15 patients with melanoma had a positive SLNB as did three of five with melanocytic proliferation. Seven of eight patients underwent CLND (one patient with blue nevus did not). Complications such as lymphedema and wound infection occurred with the completion lymphadenectomy in four patients. When this was further explored in a subsequent study, the investigators found a higher incidence of positive SLNB in a group of patients younger than 20 years with either melanoma or melanocytic lesions (40%) as compared to a group of adults (18%).72 None of the pediatric patients with a positive SLNB recurred while 25% of the adults did.

More recent series further document that positive SLNB is associated with a 10–15% of positive CLND and that the breakpoint in prognostic value appears to lie at puberty, with a higher incidence of SNLB in those <10years of age, but a worse prognosis for the older cohort.43,73–75 These series and others suggest that while SLNB is feasible, it may not be of sufficient value or benefit to the patient.76 As in adults, SLNB provides prognostic value, but does not affect outcomes. Also, there is no survival benefit to immediate CLND vs. observation, and the morbidity of this second procedure must be considered carefully. The biological differences between pre-pubescent and older patients based on tumor thickness must somehow be related in part to local conditions including a relative difference in skin thickness, altered dermal immune reactivity, and perhaps altered lymphatic drainage thresholds.

Adjuvant therapies include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and immunotherapy.77 Despite the encouraging reports from the mid-1980s, the use of cytotoxic agents has a limited role in current adjuvant therapy. Combination protocols using cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dactinomycin, or single agent dacarbazine and isolated regional perfusion with melphalan, were also reported to be effective, but did not provide for improved long-term outcomes. Radiation therapy has limited applicability and is primarily reserved for palliation. Most active trials and current research focus on immunomodulating agents, such as interleukin 2 (IL-2) and interferon alpha (IFN-α2b). In limited series, these agents have shown the ability to induce partial and even total remission.77 The use of high dose IFN-α is limited to patients with high risk, resected tumors and involvement of the nodal basin. It appears that the early use of IFN-α contributes to improved relapse-free survival in these patients.36 There have been conflicting reports about pediatric patients being able to tolerate high-dose interferon regimens. In one series, no dose reduction was necessary,78 but was needed in 50% of patients in another series.79 Vaccines have also been tried and consist of either polyvalent vaccines or defined melanoma antigens such as the ganglioside GM2, which is the most immunogenic ganglioside expressed on melanoma cells. More recent reports on the use of heat shock proteins as vehicles for the vaccines have been encouraging.38,80 Further advances in our understanding of the germline and somatic mutations in melanoma are potential new therapeutic targets.81

Outcome and Prognosis

Statistics for pediatric specific studies on melanoma are limited. The most recent focused report from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database indicated that patients under 20 had an overall 5-year survival of 93.6%. The hazard ratio of death from melanoma increased for male gender, increased age, and more advanced disease as well as for location other than trunk or extremity.82 This compares favorably with an older review which showed overall 5-year survival rates at 34% for stage 4 patients and as high as 90% for stage 1 and 2 patients.83 The most important prognostic parameters remain thickness of tumor and the clinical stage of disease. There appears to be a biologic difference in prepubertal children as compared to adolescents, particularly when evaluating positive SLN status and tumor thickness, although this does not translate into a difference in overall survival and event-free survival.43,84

Postoperative follow-up is best performed under strict guidelines. Risk-adapted, scheduled follow-up examinations in the German protocols have been validated for 3-monthly intervals during the first 5 years and every 6 months for the next 5 years.35 With this, 83% of all recurrences were identified on screening rather than by the patient (17%). Fifty per cent were detected sufficiently early that complete excision was possible. These authors further stratified risk by indicating that patients with thin melanoma lesions could undergo surveillance by physical examination rather than a technology-based system every 6 months. Those with lesions greater than 1mm thick should undergo lymph node ultrasound and determination of the S100 tumor marker protein.

References

1. Sugarman, JL. Epidermal nevus syndromes. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007; 26:221–230.

2. Rosen, H, Schmidt, B, Lan, HP, et al. Management of nevus sebaceous and the risk of basal cell carcinoma: An 18 year review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009; 26:676–681.

3. Marghoob, AA, Schoenbach, SP, Kopf, AW, et al. Large congenital melanocytic nevi and the risk for the development of malignant melanoma. A prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 1996; 132:170–175.

4. Arneja, JS, Gosain, AK. Giant congenital melanocytic nevi. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007; 120:26e–40e.

5. Ramaswamy, V, Delaney, H, Haque, S, et al. Spectrum of central nervous system abnormalities in neurocutaneous melanocytosis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012; 54:563–568.

6. Di Rocco, F, Sabatino, G, Koutzoglou, M, et al. Neurocutaneous melanosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004; 20:23–28.

7. Ilyas, EN, Goldsmith, K, Lintner, R, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma arising in a giant congenital melanocytic nevus. Cutis. 2004; 73:39–43.

8. Leech, SN, Bell, H, Leonard, N, et al. Neonatal giant congenital nevi with proliferative nodules: A clinicopathologic study and literature review of neonatal melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2004; 140:83–88.

9. Xu, X, Bellucci, KS, Elenitsas, R, et al. Cellular nodules in congenital pattern nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:153–159.

10. Warner, PM, Yakuboff, KP, Kagan, RJ, et al. An 18 year experience in the management of congenital nevomelanocytic nevi. Ann Plast Surg. 2008; 60:283–287.

11. Stegmaier, OC. Natural regression of the melanocytic nevus. J Invest Dermatol. 1959; 32:413–421.

12. Siskind, V, Darlington, S, Green, L, Green, A. Evolution of melanocytic nevi on the faces and necks of adolescents: A 4-year longitudinal study. J Invest Dermatol. 2002; 118:500–504.

13. Schaffer, JV. Pigmented lesions in children: When to worry. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007; 19:430–440.

14. Harrison, SL, Buettner, PG, Maclennan, R. The north Queensland ‘sun-safe clothing’ study: Design and baseline results of a randomized trial to determine the effectiveness of sun-protective clothing in preventing melanocytic nevi. Am J Epidemiol. 2005; 161:536–545.

15. Holman, CD, Armstrong, BK. Cutaneous malignant melanoma and indicators of total accumulated exposure to the sun: An analysis separating histogenetic types. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984; 73:75–82.

16. Oliveria, SA, Saraiya, M, Geller, AC, et al. Sun exposure and risk of melanoma. Arch Dis Child. 2006; 91:131–138.

17. Scope, A, Dusza, SW, Halpern, AC, et al. The ‘ugly duckling’ sign: Agreement between observers. Arch Dermatol. 2008; 144:58–64.

18. Heliasos, E, Kerner, M, Jaimes, N, et al. Dermoscopy for the pediatric dermatologist: Part III: Dermoscopy for melanocytic lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012; 1–12.

19. Berk, DR, LaBuz, E, Dadras, SS, et al. Melanoma and melanocytic tumors of uncertain malignant potential in children and young adults- the Stanford experience 1995-2008. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012; 27:244–254.

20. Hill, SJ, Delman, KA. Pediatric melanomas and the atypical spitzoid melanocytic neoplasms. Am J Surg. 2012; 203:761–767.

21. Dahlstrom, JE, Scolyer, RA, Thompson, JF, et al. Spitz naevus: Diagnostic problems and their management implications. Pathology. 2004; 36:452–457.

22. Luo, S, Sepehr, A, Tsao, H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid neoplasms. J AM Acad Dermatol. 2011; 65:1087–1092.

23. Ghazi, B, Carlson, GW, Murray, DR, et al. Utility of lymph node assessment for atypical melanocytic neoplasms. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010; 17:2471–2475.

24. Cerrato, F, Wallins, JS, Webb, ML, et al. Outcomes in pediatric atypical spitz tumors treated without sentinel lymph node biopsy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012; 29:448–453.

25. Ferguson, RE, Jr., Vasconez, HC. Laser treatment of congenital nevi. J Craniofac Surg. 2005; 16:908–914.

26. Harrison-Balestra, C, Gugic, D, Vincek, V. Clinically distinct form of acquired dermal melanocytosis with review of published work. J Dermatol. 2007; 34:178–182.

27. Hosler, GA, Moresi, JM, Barrett, TL. Nevi with site-related atypia: A review of melanocytic nevi with atypical histologic features based on anatomic site. J Cutan Pathol. 2008; 35:889–898.

28. Gupta, M, Berk, DR, Gray, C, et al. Morphologic features and natural history of scalp nevi in children. Arch Dermatol. 2010; 146:506–511.

29. Saida, T, Miyazaki, A, Oguchi, S, et al. Significance of dermoscopic patterns in detecting malignant melanoma on acral volar skin: Results of a multicenter study in Japan. Arch Dermatol. 2004; 140:1233–1238.

30. Braun, RP, Baran, R, Le Gal, FA, et al. Diagnosis and management of nail pigmentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007; 56:835–847.

31. Iorizzo, M, Tosti, A, Di Chiacchio, N, et al. Nail melanoma in children: Differential diagnosis and management. Dermatol Surg. 2008; 34:974–978.

32. Buchner, A, Merrell, PW, Carpenter, WM. Relative frequency of solitary melanocytic lesions of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004; 33:550–557.

33. Gleason, BC, Hirsch, MS, Nucci, MR, et al. Atypical genital nevi. A clinicopathologic analysis of 56 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008; 32:51–57.

34. Ferrari, A, Bono, A, Baldi, M, et al. Does melanoma behave differently in younger children than in adults? A retrospective study of 33 cases of childhood melanoma from a single institution. Pediatrics. 2005; 115:649–654.

35. Garbe, C, Eigentler, TK. Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous melanoma: State of the art 2006. Melanoma Res. 2007; 17:117–127.

36. Neier, M, Pappo, A, Navid, F. Management of melanomas in children and young adults. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012; 34:S51–S54.

37. Whiteman, D, Valery, P, McWhirter, W, et al. Incidence of cutaneous childhood melanoma in Queensland, Australia. Int J Cancer. 1995; 63:765–768.

38. Huynh, PM, Grant-Kels, JM, Grin, CM. Childhood melanoma: Update and treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2005; 44:715–723.

39. Massone, C, Di Stefani, A, Soyer, HP. Dermoscopy for skin cancer detection. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005; 17:147–153.

40. Friedman, RJ, Gutkowicz-Krusin, D, Farber, MJ, et al. The diagnostic performance of expert dermoscopists vs. a computer-vision system on small-diameter melanomas. Arch Dermatol. 2008; 144:476–482.

41. Bishop, JN, Harland, M, Randerson-Moor, J, et al. Management of familial melanoma. Lancet Oncol. 2007; 8:46–54.

42. Pho, L, Grossman, D, Leachman, SA. Melanoma genetics: A review of genetic factors and clinical phenotypes in familial melanoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2006; 18:173–179.

43. Paradela, A, Fonseca, E, Pita-Fernandez, S, et al. Prognostic factors for melanoma in children and adolescents. Cancer. 2010; 116:4334–4344.

44. Neier, M, Pappo, A, Navid, F. Management of melanomas in children and young adults. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012; 34:S51–S54.

45. Downard, CD, Rapkin, LB, Gow, KW. Melanoma in children and adolescents. Surg Oncol. 2007; 16:215–220.

46. Tannous, ZS, Mihm, MC, Jr., Sober, AJ, et al. Congenital melanocytic nevi: Clinical and histopathologic features, risk of melanoma, and clinical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005; 52:197–203.

47. Krengel, S, Hauschild, A, Schafer, T. Melanoma risk in congenital melanocytic naevi: A systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2006; 155:1–8.

48. Ruiz-Maldonado, R, Tamayo, L, Laterza, AM, et al. Giant pigmented nevi: Clinical, histopathologic and therapeutic considerations. J Pediatr. 1992; 120:906–911.

49. Marghoob, AA, Schoenbach, SP, Kopf, AW, et al. Large congenital melanocytic nevi and the risk for development of malignant melanoma. A prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 1996; 132:170–175.

50. Herron, MD, Vanderhooft, SL, Smock, K, et al. Proliferative nodules in congenital melanocytic nevi: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004; 28:1017–1025.

51. Illig, LF, Weidner, M, Hundeiker, H, et al. Congenital nevi less than or equal to 10 cm as precursors to melanoma. 52 cases, a review, and a new conception. Arch Dermatol. 1985; 121:1274–1281.

52. Rhodes, AR, Melski, JW. Small congenital nevocellular nevi and the risk of cutaneous melanoma. J Pediatr. 1982; 100:219–224.

53. Kraemer, KH, Lee, MM, Scotto, J. Xeroderma pigentosum: Cutaneous, ocular, and neurologic abnormalities in 830 published cases. Arch Dermatol. 1987; 123:241–250.

54. Ruiz-Maldonado, R, Orozco-Covarrubias, ML. Malignant melanoma in children. A review. Arch Dermatol. 1997; 133:363–371.

55. Baird, EA, McHenry, PM, MacKie, RM. Effect of maintenance chemotherapy in childhood on numbers of melanocytic naevi. Br Med J. 1992; 305:799–801.

56. Matichard, E, Le Henanff, A, Sanders, A, et al. Effect of neonatal phototherapy on melanocytic nevus count in children. Arch Dermatol. 2006; 142:1599–1604.

57. Jafarian, F, Powell, J, Kokta, V, et al. Malignant melanoma in childhood and adolescence: Report of 13 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005; 53:816–822.

58. Robinson, JK, Nickoloff, BJ. Digital epiluminescence microscopy monitoring of high-risk patients. Arch Dermatol. 2004; 140:49–56.

59. Massone, C, Wurm, EM, Hofmann-Wellenhof, R, et al. Teledermatology: An update. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008; 27:101–105.

60. Banky, JP, Kelly, JW, English, DR, et al. Incidence of new and changed nevi and melanomas detected using baseline images and dermoscopy in patients at high risk for melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2005; 141:998–1006.

61. Busam, KJ, Pulitzer, M. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with diagnostically controversial spitzoid melanocytic tumors? Adv Anat Pathol. 2008; 15:253–262.

62. Mills, OL, Marzban, S, Zagar, JS, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in atypical melanocytic neoplasms in childhood: A single institution experience in 24 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2012; 39:331–336.

63. Takata, M, Lin, J, Takayanagi, S, et al. Genetic and epigenetic alterations in the differential diagnosis of malignant melanoma and spitzoid lesion. Br J Dermatol. 2007; 156:1287–1294.

64. Tom, WL, Hsu, JW, Eichenfield, LF, et al. Pediatric ‘STUMP’ lesions: Evaluation and management of difficult atypical spitzoid lesions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011; 64:559–572.

65. Raskin, L, Ludgate, M, Iyer, RK, et al. Copy number variations and clinical outcome in atypical spitz tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011; 35:243–252.

66. Ali, L, Helm, T, Cheney, R, et al. Correlating array comparative genomic hybridization findings with histology and outcome in spitzoid melanocytic neoplasms. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010; 3:593–599.

67. Sepehr, A, Chao, E, Trefrey, B, et al. Longterm outcome of Spitz-type melanocytic tumors. Arch Dermatol. 2011; 147:1173–1179.

68. Balch, CM, Buzaid, AC, Soong, SJ, et al. Final version of the American Joint Committee On Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001; 19:3635–3648.

69. Been, LB, Suurmeijer, AJ, Cobben, DC, et al. [18F]FLT-PET in oncology: Current status and opportunities. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004; 31:1659–1672.

70. Kumar, R, Alavi, A. Clinical applications of fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography in the management of malignant melanoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005; 17:154–159.

71. Roaten, JB, Partrick, DA, Pearlman, N, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma and other melanocytic tumors in adolescents. J Pediatr Surg. 2005; 40:232–235.

72. Roaten, JB, Partrick, DA, Bensard, D, et al. Survival in sentinel lymph node-positive pediatric melanoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2005; 40:988–992.

73. Howman-Giles, R, Shaw, HM, Scolyer, RA, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in pediatric and adolescent cutaneous melanoma patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010; 17:138–143.

74. Han, D, Zager, JS, Han, G, et al. The unique clinical characteristics of melanoma diagnosed in children. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012; 19:3888–3895.

75. Mu, E, Lange, JR, Strouse, JJ. Comparison of the use and results of sentinel lymph node biopsy in children and young adults with melanoma. Cancer. 2012; 118:2700–2707.

76. Butter, A, Hui, T, Chapdelaine, J, et al. Melanoma in children and the use of sentinel lymph node biopsy. J Pediatr Surg. 2005; 40:797–800.

77. Ascierto, PA, Scala, S, Ottaiano, A, et al. Adjuvant treatment of malignant melanoma: Where are we? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006; 57:45–52.

78. Chao, MM, Schwartz, JL, Wechsler, DS, et al. High-risk surgically resected pediatric melanoma and adjuvant interferon therapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005; 44:441–448.

79. Shah, NC, Gerstle, JT, Stuart, M, et al. Use of sentinel lymph node biopsy and high-dose interferon in pediatric patients with high-risk melanoma: The Hospital for Sick Children experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006; 28:496–500.

80. Ralph, SJ. An update on malignant melanoma vaccine research: Insights into mechanisms for improving the design and potency of melanoma therapeutic vaccines. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007; 8:123–141.

81. Kirkwood, JM, Jukic, D, Averbrook, BJ, et al. Melanoma in pediatric, adolescent and young adult patients. Semin Oncol. 2009; 36:419–431.

82. Strouse, JJ, Fears, TR, Tucker, MA, et al. Pediatric melanoma: Risk factor and survival analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology and end results database. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23:4735–4741.

83. Tate, PS, Ronan, SG, Feucht, KA, et al. Melanoma in childhood and adolescence: Clinical and pathological features of 48 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1993; 28:217–222.

84. Moore-Olufema, S, Herzog, C, Warneke, C, et al. Outcomes in pediatric melanoma comparing prepubertal to adolescent pediatric patients. Ann Surg. 2011; 253:1211–1215.