CHAPTER 164 Neurosurgical Management of Intractable Pain

Prelude to Surgical Treatment

Acute pain is a signal of actual or impending tissue injury and is generated by activation of nociceptors in tissue that has sustained an injury or insult. Acute pain resolves as injured tissue heals. Chronic pain, conversely, outlasts the typical period required for healing of an acute injury. Some definitions of chronic pain are based on the duration of pain (e.g., pain that lasts longer than 3 or 6 months). This is not an accurate distinction, however, because different types of acute injury require different lengths of healing time, and the transition of acute pain to chronic pain can vary according to the nature of the injury.1

Although sometimes difficult to make, the distinction between acute and chronic pain is important. Treatment of acute pain should be aimed at achieving analgesia while promoting tissue healing. This treatment might include rest or immobilization, analgesics, and passive physical therapy.2 In contrast, chronic pain does not serve a useful physiologic purpose (unless tissue injury is ongoing). In some cases, chronic pain no longer reflects disease but instead is considered a disease itself.3 Physical deconditioning is also a common accompaniment of many chronic pain disorders, such as failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS). Thus, many patients with chronic pain require physical reactivation and rehabilitation rather than the rest and relaxation recommended in the treatment of acute pain. This means that chronic pain often requires a treatment program opposite that used to treat acute pain and that the distinction between acute and chronic pain is critical because treating chronic pain as acute pain only promotes further disuse and deconditioning.2 The differentiation of acute and chronic pain is also important because psychological and social factors that can complicate a pain complaint might be more common in patients with chronic as opposed to acute pain. In fact, in some cases, psychosocial factors can be the predominant cause of a complaint of chronic pain.

The distinction between nociceptive and neuropathic pain is also important because the two types of pain usually respond differently to specific treatments. Nociceptive pain is generated when injury or disease (e.g., a broken arm, cancer pain with local tissue invasion) activates the nociceptors that stimulate central nervous system nociceptive pathways. Nociceptive pain, which patients describe as “throbbing,” “aching,” or “dull,”4 is thus a normal, protective response of the nociceptive systems. In contrast, neuropathic pain is the result of a pathologic process (injury or disease) affecting the peripheral or central nervous system. Such neuronal injury leads to abnormal neuronal excitability, spontaneous discharges, and ephaptic transmission, which might, in turn, lead to generation of pain with or without peripheral, let alone nociceptive, input. Thus, in contrast to nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain reflects abnormal neuronal activity. Neuropathic pain, which patients describe as “burning,” “shooting,” “tingling,” or “shock-like,”4 can be continuous or paroxysmal (lancinating). Although nociceptive pain usually responds to opioids (e.g., the pain of a broken arm can be treated with morphine), neuropathic pain tends to resist opioid treatment (at least at typical doses) and frequently requires treatment with nonopioid medications.

Surgical treatment of intractable pain is not usually the first treatment option. In most cases, treatment of intractable pain should follow a rational process with the simplest, safest methods used first and interventional treatments reserved for later use.4 A simple way of picturing this approach is a pain treatment ladder, similar to the one proposed by the World Health Organization.5 On the lowest rungs are the simplest, safest measures. Each higher rung reflects a more invasive treatment, which, just like climbing to higher rungs on a ladder, entails greater risk should complications arise. Medical therapy, beginning typically with nonopioids (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications) in conjunction with adjuvant therapies when appropriate, should generally precede surgical intervention. If adequate pain control is not obtained with nonopioids, mild opioids might be required, to be replaced by strong opioids if necessary. In most cases, pain relief is most readily achieved using scheduled rather than “as needed” analgesic dosing.6,7 Neuropathic pain frequently requires treatment with nonopioid medication, although opioids can be helpful for some patients. For continuous neuropathic pain (e.g., constant burning, dysesthetic pain), useful adjuvant medications include antidepressants (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline), clonidine, local anesthetics (e.g., mexiletine), and capsaicin cream.7 Paroxysmal, lancinating, or evoked neuropathic pain might improve with anticonvulsants (e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin, gabapentin) or baclofen.7 Nonpharmacologic adjuvant therapy, including psychological support, relaxation therapies, coping strategies, passive physical therapy (e.g., massage, heat/cold), transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, and orthoses)6,7 can be useful in the treatment of nociceptive or neuropathic pain.

Patient Selection for Surgical Pain Therapies

In most cases, surgical intervention is reserved for patients in whom conservative therapies result in inadequate pain relief or are associated with unacceptable side effects or risks; no absolute contradictions to surgery exist; and treatment of the underlying cause of pain is not possible, practical, or appropriate.4,8 For example, radicular leg pain from lumbar spinal stenosis can be treated with decompressive lumbar laminectomy; however, if a patient also has severe coronary artery disease that increases operative risk or has persistent pain after prior spinal surgery that reduces the potential benefit of surgery, SCS might be the safest and most appropriate treatment.8,9

The pain should have a definable organic cause. It is especially important to identify the cause of chronic pain of nonmalignant origin in order to reduce the likelihood of significant underlying or primary psychological dysfunction. Psychological dysfunction can be common in patients with chronic pain disorders and might preclude a good outcome to surgical treatment. Thus, a formal psychological evaluation might be appropriate for many (or most) patients being considered for surgical treatment of intractable pain. Contraindications to surgical intervention include overt psychological dysfunction, such as active psychosis, suicidal or homicidal behavior, major uncontrolled depression or anxiety, serious alcohol or drug abuse, or serious cognitive deficits. Other psychological problems, which may be viewed as “risk factors,” include somatization disorder, personality disorders (e.g., borderline or antisocial), history of serious abuse, major issues of secondary gain, nonorganic signs on physical examination, unusual pain ratings (e.g., 12 on a 10-point scale), inadequate social support, unrealistic outcome expectations, and, in the case of implantable augmentative devices, an inability to understand the device or its use. Patients with psychological risk factors are not necessarily precluded from surgical treatment, but the treatment program should address the psychological issues to facilitate a good outcome.10

Neurosurgical Therapies for Intractable Pain

Neurosurgeons can use anatomic, augmentative (or neuromodulation), and ablative therapies (Table 164-1).11 The treatment offered should be tailored to meet the needs of each individual patient and the skills of the treating physician. Specific interventions vary in their appropriateness as a treatment for pain in specific body regions (Tables 164-2 through 164-5). Patient-related factors that must be taken into consideration when selecting a therapy include the etiology, distribution, and characteristics (nociceptive or neuropathic) of the pain; life expectancy; and psychological, social, and economic issues relevant to the pain complaint. The relative advantages and disadvantages of anatomic, augmentative, and ablative therapies should be weighed in view of these factors, and a choice among these three general approaches should be made before choosing a specific intervention. Selecting the right treatment for the right patient at the right time increases the likelihood of a successful outcome.

| ANATOMIC | AUGMENTATIVE | ABLATIVE |

|---|---|---|

| Correction of structural deformity |

DREZ, dorsal root entry zone.

Modified from North RB. Neurosurgical procedures for chronic pain: general neurosurgical practice. Clin Neurosurg. 1992;40:182-196.

TABLE 164-2 Neurosurgical Procedures for Treatment of Head and Neck Pain

| AUGMENTATIVE |

| ABLATIVE |

TABLE 164-3 Neurosurgical Procedures for Treatment of Upper Trunk, Shoulder, and Arm Pain

| AUGMENTATIVE |

| ABLATIVE |

TABLE 164-4 Neurosurgical Procedures for Treatment of Lower Trunk and Leg Pain

| AUGMENTATIVE |

| ABLATIVE |

TABLE 164-5 Neurosurgical Procedures for Treatment of Diffuse Pain

| AUGMENTATIVE |

| ABLATIVE |

Ablative therapies, however, have a role in the treatment of certain pain syndromes12,13 and can target almost every level of the peripheral and central nervous systems. Thus, ablative therapies can be directed at preventing transmission of nociceptive information into the central nervous system at the level of peripheral nerves (neurectomy, neurotomy), roots (ganglionectomy, rhizotomy), and the spinal cord dorsal horn (DREZ, including nucleus caudalis DREZ). Ascending nociceptive pathways can be disrupted at the level of the spinal cord or brainstem (cordotomy, myelotomy, tractotomy) or within the brain (thalamotomy, cingulotomy).

Augmentative Therapies

Stimulation therapies approved for use in the United States include SCS and PNS. The major indication for SCS is for treatment of neuropathic pain in an extremity. The pain should be relatively focal (e.g., localized to one or two extremities or focal on the trunk) and static in nature. Common applications include treatment of persistent radicular pain associated with FBSS8,9,14–19 or neuropathic pain related to complex regional pain syndrome (“reflex sympathetic dystrophy”).20,21 In the FBSS population, the success rate (defined typically as 50% or greater reduction in pain) is about 60% at 5 years.8,15,16 Patients with complex regional pain syndromes have similar outcomes, although success rates as high as 70% to 100% have been reported.20,21 SCS can also be effective for neuropathic pain affecting the trunk (e.g., postherpetic neuralgia and some types of postthoracotomy pain) and for extremity pain due to peripheral neuropathy,22 root injury, phantom limb syndrome (but not necessarily postamputation stump pain), and peripheral vascular disease.23,24 SCS is widely used in Europe as a successful treatment of refractory angina pectoris,25,26 but this indication does not have specific U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.

The indications for PNS are similar to those for SCS, except that the distribution of pain should be limited to the territory of a single peripheral nerve.27 Overlap exists between the application of SCS and PNS. Extremity pain that might be appropriate for PNS can sometimes be treated equally well with SCS, and many surgeons find it easier to implant a percutaneous SCS electrode than to implant a PNS electrode (which usually requires an open procedure). Some situations clearly require PNS rather than SCS, for example, treatment of occipital neuralgia or cranial postherpetic neuralgia.28

Intracranial stimulation therapies include DBS of the somatosensory thalamus, hypothalamus, and periventricular-periaqueductal gray29–34 or MCS.35–38 These therapies are used primarily for treating pain of nonmalignant origin, such as pain associated with FBSS, neuropathic pain following central or peripheral nervous system injury, or trigeminal pain or cluster headache. Neither DBS nor MCS is approved by the FDA for the treatment of pain, although DBS has been used for more than two decades.

Targets for focal electrical stimulation of the brain include the ventrocaudal nucleus (nucleus ventroposterolateralis and ventroposteromedialis) and the periventricular-periaqueductal gray (PVG-PAG). Stimulation sites for DBS are generally chosen on the basis of the pain characteristics. Nociceptive pain and paroxysmal, lancinating, or evoked neuropathic pain (e.g., allodynia, hyperpathia) tend to respond to PVG-PAG stimulation, which might activate endogenous opioid systems. Continuous neuropathic pain responds most consistently to paresthesia-producing stimulation of the sensory thalamus (nucleus ventrocaudalis).32 Because many pain syndromes (e.g., cancer pain, FBSS) have mixed components of nociceptive and neuropathic pain, some physicians offer the patient a screening trial using electrodes in both regions to determine which provides the best pain relief. Patients might also be given a morphine-naloxone test to clarify the extent of nociceptive and neuropathic pain components and facilitate selection of the best stimulation target.30

Success rates of DBS for the treatment of intractable pain are difficult to determine because patient selection, techniques, and outcomes assessments vary substantially among studies. About 60% to 80% of patients undergoing a screening trial with DBS will have pain relief sufficient to warrant implantation of a permanent stimulation system. Of those who receive a permanent stimulation system, about 25% to 80% (generally 50% to 60%)29 will gain acceptable long-term pain relief.29–33 Patients with cancer pain,32 FBSS, peripheral neuropathy, and trigeminal neuropathy (not anesthesia dolorosa)29,30,32 tend to respond to DBS more favorably than patients with central pain syndromes (e.g., thalamic pain, spinal cord injury pain, anesthesia dolorosa, postherpetic neuralgia, or phantom limb pain).29,30,32 The incidence of serious complications of DBS is low, but the combined incidence of morbidity, mortality, and technical complications can approach 25% to 30%.29,32

MCS has received attention as an alternative to thalamic and PAG-PVG stimulation.35–38 MCS is used primarily for treatment of neuropathic pain syndromes and might be particularly effective for certain varieties of intractable facial pain (e.g., trigeminal neuropathic pain).36 About 50% of patients undergoing MCS have good long-term pain relief. As with DBS, MCS appears most effective when used in the absence of anesthesia in the distribution of pain being treated. Compared with DBS, the overall clinical efficacy of MCS is similar, but the complications associated with MCS might be less serious because the electrode is placed epidurally rather than directly on or within the brain parenchyma. MCS is a promising therapy whose long-term efficacy is under active investigation at several centers.

Neuraxial drug infusion has become a popular interventional treatment for intractable pain,39–44 especially for pain with a significant nociceptive component. Thus, the use of intrathecal analgesics for the treatment of cancer pain is well accepted. In contrast, the use of this therapy for chronic nonmalignant pain has been controversial,44 reflecting concern that neuropathic pain (common in chronic nonmalignant pain syndromes) does not respond adequately to opioids and that the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of neuraxial drug infusion for neuropathic pain have not been determined in controlled trials. Despite these concerns, intrathecal analgesic therapy has been used to treat neuropathic pain conditions with favorable results,40,41,43 and the most common indication for intrathecal analgesic administration is FBSS, which typically includes components of nociceptive (low back) and neuropathic (extremity) pain.

The key advantage of neuraxial analgesic administration is its versatility, which allows it to be applied to a wide range of indications, including nociceptive and mixed nociceptive-neuropathic pain syndromes. It can be used to treat focal or diffuse axial and extremity pain. Neuraxial analgesia is commonly used to treat pain below cervical levels but can be effective for head and neck pain, especially if analgesic agents are delivered intraventricularly.45,46 Neuraxial analgesics can also treat changing pain (e.g., in a patient with progressive cancer). Significant disadvantages of neuraxial analgesics include the high cost of the device and medication and the need for maintenance (e.g., refilling and, in the case of programmable pumps, replacement of depleted batteries). About 60% to 80% of patients with neuraxial analgesics achieve good long-term relief of pain, and, despite the controversy about the use of neuraxial analgesics for noncancer pain, outcomes are similar (degree of pain relief, patient satisfaction, and dose requirements) in patients with cancer and noncancer pain.39,40 Serious complications of the therapy are uncommon.

Ablative Therapies

Ablative therapies include peripheral techniques that interrupt or alter nociceptive input into the spinal cord (e.g., neurectomy, ganglionectomy, rhizotomy), spinal interventions that alter afferent input or rostral transmission of nociceptive information (e.g., DREZ lesioning, cordotomy, myelotomy), and supraspinal intracranial procedures that might interrupt transmission of nociceptive information (e.g., mesencephalotomy, thalamotomy) or perception of painful stimuli (e.g., cingulotomy). As with augmentative techniques, a successful outcome requires appropriate patient and intervention selection. Ablative therapies are more successful in the treatment of nociceptive pain than of neuropathic pain; when neuropathic pain is treated with ablative therapies, improvement is primarily limited to intermittent, paroxysmal, or evoked (allodynia, hyperpathia) pain, whereas continuous pain remains relatively unchanged.47

Sympathectomy has been reported to alleviate visceral pain associated with certain cancers48,49 and might be an effective treatment for noncancer pain, such as pain associated with vasospastic disorders or sympathetically maintained pain (when sympathetic blocks reliably relieve the pain). Sympathectomy, however, has fallen into disfavor as a treatment for intractable pain of nonmalignant origin because of inconsistent results and concerns about complication rates.48–52 Furthermore, data indicate that SCS, which has the advantage of reversibility, provides a better long-term outcome with lower morbidity than sympathectomy; thus, SCS might become the treatment of choice for sympathetically maintained noncancer pain.19

Neurectomy might be useful in select cases as a treatment for patients who develop pain following peripheral nerve injury, including that associated with limb amputation. If an identifiable neuroma is the cause of pain, its resection can provide significant relief.53 Neurectomy is not useful for treatment of nonspecific stump pain after amputation, however, and is not generally useful for the treatment of other nonmalignant peripheral pain syndromes. The utility of neurectomy is limited because pain arising from a pure sensory nerve is uncommon, and mixed sensory-motor nerves cannot be sectioned without risking functional impairment. Some specific exceptions to this general observation exist, however; for example, section of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve might provide long-lasting relief of meralgia paresthetica,54 and section of the ilioinguinal or genitofemoral nerves might relieve some inguinal pain syndromes (e.g., postherniorrhaphy pain) in properly selected patients.55,56 Radiofrequency facet denervation might provide substantial relief of neck or back pain, albeit with significant rates of recurrence after 2 to 3 years.57

Dorsal rhizotomy and ganglionectomy serve similar purposes in denervating somatic and visceral tissues, but ganglionectomy might produce more complete denervation than can be accomplished by dorsal rhizotomy because the afferent fibers that enter the spinal cord through the ventral root58 are not affected by dorsal rhizotomy. In contrast, ganglionectomy effectively eliminates input from ventral root afferent fibers by removing their cell bodies, which are located within the dorsal root ganglion. Rhizotomy and ganglionectomy can be used to treat pain in the neck, trunk, or abdomen. Neither procedure is useful for the treatment of pain in the extremities unless function of the extremity is already lost because denervation removes proprioceptive as well as nociceptive input and produces a functionless limb. Limited denervation does not provide adequate pain relief, probably because of overlap of segmental innervation of dermatomes. These procedures are most appropriate for the treatment of cancer pain; noncancer pain does not improve consistently on a long-term basis,59,60 although ganglionectomy might be useful for relief of occipital neuralgia.61 Temporary relief by “diagnostic” blocks is nonspecific62 and might not predict success. In patients with cancer, rhizotomy and ganglionectomy might be useful for thoracic or abdominal wall pain; for perineal pain in patients with impaired bladder, bowel, and sex function; or for the treatment of pain in a functionless extremity.63 Multiple sacral rhizotomies can be performed (e.g., to treat pelvic pain from cancer) by passing a ligature around the thecal sac below S1.64 Rhizotomy might be useful for treatment of craniofacial pain65 of nontrigeminal origin as well as for classic trigeminal neuralgia.

DREZ lesioning of the spinal cord (for trunk or extremity pain)66–70 or of the nucleus caudalis (for facial pain)67,70–72 can provide significant pain relief in properly selected patients, with improvement in pain reported in 60% to 80%. These techniques, however, are best reserved for localized pain. Certain types of cancer pain can be treated effectively with DREZ lesioning (e.g., neuropathic arm pain associated with Pancoast’s tumor), but the most successful applications are related to treatment of neuropathic pain arising from root avulsion (cervical or lumbosacral) and “end-zone” or “boundary” pain after spinal cord injury. These pain syndromes sometimes respond adequately to SCS or intrathecal drug infusion, but DREZ lesioning might provide a similar result without the need for long-term maintenance of an augmentative device. DREZ lesioning has been used for the treatment of other neuropathic pain syndromes (e.g., postherpetic neuralgia), but good pain relief is not achieved consistently. Nucleus caudalis lesioning appears most useful for deafferentation pain affecting the face (including postherpetic neuralgia) and less helpful for facial pain of peripheral origin (e.g., traumatic trigeminal neuropathy). As with other ablative procedures, DREZ lesioning is most effective for relieving paroxysmal rather than continuous pain.68

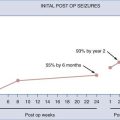

Cordotomy is used most commonly for the treatment of cancer-related pain below mid to low cervical dermatomes. It is used less frequently to manage noncancer pain because of concern about the potential loss of pain relief over time, the occurrence of postcordotomy dysesthesia, and the risk for complications.73,74 Cordotomy can be performed as an open73,75 or closed (percutaneous)76–78 procedure. Percutaneous techniques are less invasive, but open techniques remain viable options because some surgeons lack the expertise and equipment required for percutaneous procedures.

In general, the level of analgesia produced by cordotomy decreases over time such that within 3 weeks after the procedure, the level has fallen three to six spinal levels, and by 6 months, the level might have fallen six to eight segments. Consequently, the procedure is best for pain below midcervical levels.73,76–78 Both lancinating, paroxysmal neuropathic pain that sometimes arises from spinal cord injury and evoked (allodynic or hyperpathic) pain associated with peripheral neuropathic pain syndromes can improve following cordotomy, but continuous neuropathic pain does not improve.76

Lateral pain responds better than midline or axial pain (e.g., visceral pain), which might require a bilateral procedure. The utility of bilateral cordotomy is compromised by the attendant risk for weakness; bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction; and respiratory depression (if the procedure is performed bilaterally at cervical levels).73,76 The risk for respiratory depression subsequent to a unilateral cervical procedure mandates that pulmonary function be acceptable on the contralateral side. For example, a patient who has undergone previous pneumonectomy for lung cancer should not undergo cordotomy that would compromise pulmonary function on the side of the remaining lung.76 In some patients, however, bilateral cordotomy might be necessary. Bilateral high (C1-2) percutaneous cordotomy is not generally recommended owing to a relatively high risk for sleep apnea and other complications. An alternative approach is to perform a unilateral high cervical procedure followed by a contralateral low cervical procedure or open thoracic cordotomy.73,74 Open cordotomy might be advantageous if a bilateral procedure is required because both sides can be treated safely at one time by separating the operated levels by several spinal segments. In contrast, percutaneous (cervical) procedures are typically staged at least 1 week apart.73

Cordotomy provides good pain relief in about 60% to 80% of patients,76,79 but loss of pain relief tends to occur over time. About one third of patients have recurrent pain in 3 months, half at 1 year, and two thirds at longer follow-up intervals.63,79,80 The gradual recurrence of pain over months to years and the potential development of postcordotomy dysesthetic pain limit the usefulness of this technique in patients with pain syndromes of nonmalignant origin, who typically have long life expectancies.73

Myelotomy has also fallen into disuse subsequent to the advent of intrathecal drug infusion therapy but can provide significant pain relief in properly selected patients, including some who fail treatment with intrathecal analgesics.81 Commissural myelotomy was developed to provide the benefits of bilateral cordotomy without the inherent risks involved in lesioning both anterior quadrants of the spinal cord.81–84 Commissural myelotomy is accomplished by sectioning spinothalamic tract fibers as they decussate in the anterior commissure. Subsequently, it was observed that a limited midline myelotomy85 or high cervical myelotomy82,84,86 could be equally effective. Recent identification of a dorsal column visceral pain pathway has led to the development of punctate midline myelotomy.84,87

A myelotomy is indicated primarily for the treatment of cancer pain, generally in the abdomen, pelvis, perineum, or legs. The advantage compared with cordotomy is that bilateral and midline pain can be treated with a single operative procedure, with lower morbidity and mortality. A myelotomy is most effective for nociceptive rather than neuropathic pain and should be of particular utility to most neurosurgeons because the various techniques are straightforward and the anatomy is familiar. Early complete pain relief is achieved in most patients (more than 90%), but pain tends to recur over time; nevertheless, about 50% to 60% of patients have good long-term pain relief.78,86 The risk for bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction is less than that associated with bilateral cordotomy but remains sufficiently high so that use of myelotomy procedures is restricted in most cases to patients with cancer pain who have preexisting dysfunction.63

Ablative neurosurgical procedures directed at the brainstem are not in widespread use, in part because relatively few patients require such interventions and because relatively few neurosurgeons have the expertise to perform them. As with other ablative procedures, however, they can provide significant benefit in carefully selected patients. Mesencephalotomy, which is indicated for the treatment of intractable pain involving the head, neck, shoulder, and arm,47,88,89 can be viewed as a supraspinal version of cordotomy.47 Mesencephalotomy is commonly used for the treatment of cancer pain and results in long-term pain relief in 85% of patients.86 Mesencephalotomy, however, does not provide consistent long-term relief of central neuropathic pain88 and is associated with frequent side effects and complications, especially oculomotor dysfunction.47,86,88 The utility of mesencephalotomy has diminished subsequent to the advent of neuraxial analgesic administration: intraventricular morphine infusion can provide good pain relief with a lower incidence of complications. Mesencephalotomy, however, might be the preferred therapy for some patients, for example, those with short life expectancies or for whom the cost of long-term follow-up required with neuraxial analgesic administration becomes burdensome.

Thalamotomy has been used for the treatment of cancer and noncancer pain and can be accomplished by stereotactic radiofrequency47,86,90–92 or radiosurgical93,94 techniques. As a treatment of cancer pain, thalamotomy is most appropriate for patients who have widespread pain (e.g., from diffuse metastatic disease), or who have midline, bilateral, or head and neck pain, for which other procedures might not provide relief.72 Thalamotomy can be useful for patients who are not candidates for cordotomy, for example, those with pain above the C5 dermatome or with pulmonary dysfunction.92 The success rate of thalamotomy in relieving pain is slightly lower than is achieved with mesencephalotomy, but the incidence of complications is lower with thalamotomy.92 The lateral thalamus (nucleus ventrocaudalis) is not considered an acceptable target for ablation because of the risk for dysesthesia and sensory loss,47 but the subjacent parvicellular ventrocaudal nucleus, which is thought to be a relay site for spinothalamic afferents, has been used as a target. Results of thalamotomy directed to this structure might be similar to those achieved with cordotomy.90 Medial thalamotomy appears to be most effective for treating nociceptive pain (e.g., cancer pain), with acceptable long-term pain relief obtained in about 30% to 50% of patients.47,79,91,94 Overall, compared with nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain responds less consistently to thalamotomy, with only about one third of patients improving over the long term.47,91 Patients with paroxysmal, lancinating neuropathic pain or neuropathic pain with elements of allodynia and hyperpathia might improve significantly after thalamotomy, whereas those with continuous neuropathic pain tend not to benefit.47

Cingulotomy, which is used less for treatment of intractable pain than for management of psychiatric disorders, is applied most commonly to the treatment of cancer pain but has been used for noncancer pain as well.85,95–98 About 50% to 75% of patients benefit from the procedure, at least in the short term. In the cancer population, pain relief is generally maintained for at least 3 months. The utility of cingulotomy for chronic noncancer pain is less apparent; some investigators report relatively good long-lasting pain relief,86,96,98 but others indicate only 20% long-term success.89 Cingulotomy might be a reasonable option for patients, especially those with cancer pain, in whom other treatments have not worked. Because cingulotomy is performed for treatment of psychiatric disease and carries the stigma of “psychosurgery,” formal review by institutional ethics committees might be warranted if this procedure is being considered as a treatment for intractable pain.

Hypophysectomy (surgical, chemical, or radiosurgical) can provide good relief of cancer pain and is most effective for hormone-responsive cancers (e.g., prostate, breast) but might relieve pain related to other tumors as well. Hypophysectomy is most appropriate for patients with widespread disease and diffuse pain. Pain is alleviated in 45% to 95% of patients independent of tumor regression; the specific mechanism of pain relief is unknown.86,90,99–101

Acar F, Miller J, Golshani KJ, et al. Pain relief after cervical ganglionectomy (C2 and C3) for the treatment of medically intractable occipital neuralgia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2008;86:106-112.

Bittar RG, Kar-Purkayastha I, Owen SL, et al. Deep brain stimulation for pain relief: a meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:515-519.

Burchiel KJ, Johans TJ, Ochoa J. The surgical treatment of painful traumatic neuromas. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:714-719.

Deer TR. The role of neuromodulation by spinal cord stimulation in chronic pain syndromes: current concepts. Techn Reg Anes Pain Manage. 1998;2:161-167.

Doleys DM, Olson K. Psychological Assessment and Intervention in Implantable Pain Therapies. Minneapolis, MN: Medtronic Inc; 1997.

Hassenbusch SJ, Stanton-Hicks M, Schoppa D, et al. Long-term results of peripheral nerve stimulation for reflex sympathetic dystrophy. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:415-423.

Hayashi M, Taira T, Chernov M, et al. Role of pituitary radiosurgery for the management of intractable pain and potential future applications. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2003;81:75-83.

Kanpolat Y. Percutaneous destructive pain procedures on the upper spinal cord and brainstem in cancer pain: CT-guided techniques, indications, and results. Adv Stand Neurosurg. 2007;32:147-173.

Kanpolat Y, Tuna H, Bozkurt M, et al. Spinal and nucleus caudalis dorsal root entry zone operations for chronic pain. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(suppl 1):235-242.

Kaplitt M, Rezai AR, Lozano AM, et al. Deep brain stimulation for chronic pain. In: Winn HR, editor. Youmans Neurological Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:3119-3131.

Mailis A, Furlan A. Sympathectomy for pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD002918.

Nauta HJW, Hewitt E, Westlund KN, et al. Surgical interruption of a midline dorsal column visceral pain pathway. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:538-542.

Nguyen J-P, Lefaucheur J-P, Decq P, et al. Chronic motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of central and neuropathic pain. Correlations among clinical, electrophysiological and anatomical data. Pain. 1999;82:245-251.

North RB, Shipley J. Practice parameters for the use of spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2007;8(suppl 4):S200-S275.

Raslan AM, McCartney S, Burchiel KJ. Management of chronic severe pain: spinal neuromodulatory and neuroablative approaches. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97:33-41.

Sindou M, Mertens P, Wael M. Microsurgical DREZotomy for pain due to spinal cord and/or cauda equine injuries: long-term results in a series of 44 patients. Pain. 2001;92:159-171.

Smith HS, Deer TR, Staats PS, et al. Intrathecal drug delivery. Pain Physician. 2008;11:S89-S104.

Tasker RR. Percutaneous cordotomy. In: Schmidek HH, Sweet WH, editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995:1595-1611.

Velasco F, Argüelles C, Carrillo-Ruiz JD, et al. Efficacy of motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of neuropathic pain: a randomized double-blind trial. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:698-706.

Weiner RL. Occipital neurostimulation for treatment of intractable headache syndromes. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97:129-133.

Yen CP, Kung SS, Su YF, et al. Stereotactic bilateral anterior cingulotomy of intractable pain. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:886-890.

Young RF. Radiosurgery for pain management. In: Follett KA, editor. Neurosurgical Pain Management. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:237-244.

1 Bonica JJ. Definitions and taxonomy of pain. In: Bonica J, Loeser JD, Chapman CR, et al, editors. The Management of Pain. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1990:18-27.

2 Loeser JD, Bigos SJ, Fordyce WE, et al. Low back pain. In: Bonica J, Loeser JD, Chapman CR, et al, editors. The Management of Pain. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1990:1448-1483.

3 Bonica JJ. General considerations of chronic pain. In: Bonica J, Loeser JD, Chapman CR, et al, editors. The Management of Pain. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1990:180-196.

4 Krames ES. Intraspinal opioid therapy for chronic nonmalignant pain: current practice and clinical guidelines. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;11:333-352.

5 World Health Organization Expert Committee. Cancer pain relief and palliative care. World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 1990;804:1-73.

6 American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain, 3rd ed. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 1992.

7 Cherny NI, Portenoy RK. The management of cancer pain. CA Cancer J Clin. 1994;44:262-303.

8 North RB, Kidd DH, Farrokhi F, et al. Spinal cord stimulation versus repeated lumbosacral spine surgery for chronic pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:98-106.

9 North RB, Kidd D, Shipley J, et al. Spinal cord stimulation versus reoperation for failed back surgery syndrome: a cost effectiveness and cost utility analysis based on a randomized, controlled trial. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:361-369.

10 Doleys DM, Olson K. Psychological Assessment and Intervention in Implantable Pain Therapies. Minneapolis, MN: Medtronic Inc; 1997.

11 North RB, Levy RM. Consensus conference on the neurosurgical management of pain (review). Neurosurgery. 1994;34:756-761.

12 Raslan AM, McCartney S, Burchiel KJ. Management of chronic severe pain: spinal neuromodulatory and neuroablative approaches. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97:33-41.

13 Whitworth LA, Feler CA. Application of spinal ablative techniques for the treatment of benign chronic painful conditions: history, methods, and outcomes. Spine. 2002;27:2607-2612.

14 Deer TR. The role of neuromodulation by spinal cord stimulation in chronic pain syndromes: current concepts. Techn Reg Anes Pain Manage. 1998;2:161-167.

15 North RB, Kidd DH, Zahurak M, et al. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic, intractable pain: experience over two decades. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:384-395.

16 Turner J, Loeser J, Bell K. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic low back pain: a systematic literature synthesis. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:1088-1096.

17 Kumar K, Taylor RS, Jacques L, et al. Spinal cord stimulation versus conventional medical management for neuropathic pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial in patients with failed back surgery syndrome. Pain. 2007;132:179-188.

18 North RB, Shipley J. Practice parameters for the use of spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2007;8:S200-S275.

19 Burchiel KJ, Anderson VC, Brown FD, et al. Prospective, multicenter study of spinal cord stimulation for relief of chronic back and extremity pain. Spine. 1996;21:2786-2794.

20 Kumar K, Nath R, Toth C. Spinal cord stimulation is effective in the management of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:503-508.

21 Kemler MA, Barendse GAM, van Kleef M, et al. Spinal cord stimulation in patients with chronic reflex sympathetic dystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:618-624.

22 Kumar K, Nath R. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic pain in peripheral neuropathy. Surg Neurol. 1996;46:363-364.

23 Kumar K, Toth C, Nath R, et al. Improvement of limb circulation in peripheral vascular disease using epidural spinal cord stimulation: a prospective study. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:662-669.

24 Huber S, Vaglienti R, Midcap M. Enhanced limb salvage for peripheral vascular disease with the use of spinal cord stimulation. W V Med J. 1996;92:89-91.

25 Sanderson JE, Ibrahim B, Waterhouse D, et al. Spinal electrical stimulation for intractable angina—long-term clinical outcome and safety. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:810-814.

26 De Jongste MJL, Hautvast RWM, Hillege HL, et al. Efficacy of spinal cord stimulation as adjuvant therapy for intractable angina pectoris: a prospective, randomized clinical study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1592-1597.

27 Hassenbusch SJ, Stanton-Hicks M, Schoppa D, et al. Long-term results of peripheral nerve stimulation for reflex sympathetic dystrophy. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:415-423.

28 Weiner RL. Occipital neurostimulation for treatment of intractable headache syndromes. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97:129-133.

29 Levy RM, Lamb S, Adams JE. Treatment of chronic pain by deep brain stimulation: long term follow-up and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:885-893.

30 Kumar K, Toth C, Nath RK. Deep brain stimulation for intractable pain: a 15-year experience. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:736-747.

31 Richardson DE. Intracranial stimulation therapies: Deep brain stimulation. In: Follett KA, editor. Neurosurgical Pain Management. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:156-159.

32 Kaplitt M, Rezai AR, Lozano AM, et al. Deep brain stimulation for chronic pain. In: Winn HR, editor. Youmans Neurological Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:3119-3131.

33 Bittar RG, Kar-Purkayastha I, Owen SL, et al. Deep brain stimulation for pain relief: a meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:515-519.

34 Leone M, Proietti Cecchini A, et al. Lessons from 8 years’ experience of hypothalamic stimulation in cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:787-797.

35 Nguyen J-P, Lefaucheur J-P, Decq P, et al. Chronic motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of central and neuropathic pain. Correlations between clinical, electrophysiological and anatomical data. Pain. 1999;82:245-251.

36 Henderson JM, Lad SP. Motor cortex stimulation and neuropathic facial pain. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;21:E6.

37 Lima MC, Fregni F. Motor cortex stimulation for chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Neurology. 2008;70:2329-2337.

38 Velasco F, Argüelles C, Carrillo-Ruiz JD, et al. Efficacy of motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of neuropathic pain: a randomized double-blind trial. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:698-706.

39 Paice JA, Penn RD, Shott S. Intraspinal morphine for chronic pain: a retrospective, multicenter study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;11:71-80.

40 Winkelmüller M, Winkelmüller W. Long-term effects of continuous intrathecal opioid treatment in chronic pain of nonmalignant etiology. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:458-467.

41 Schuchard M, Krames ES, Lanning R. Intraspinal analgesia for nonmalignant pain. A retrospective analysis for efficacy, safety, and feasibility in 50 patients. Neuromodulation. 1998;1:46-56.

42 Smith HS, Deer TR, Staats PS, et al. Intrathecal drug delivery. Pain Physician. 2008;11:S89-S104.

43 Hassenbusch SJ, Stanton-Hicks M, Covington EC, et al. Long-term intraspinal infusions of opioids in the treatment of neuropathic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:527-543.

44 Maron J, Loeser JD. Spinal opioid infusions in the treatment of chronic pain of nonmalignant origin (review). Clin J Pain. 1996;12:174-179.

45 Dennis GC, DeWitty RL. Long-term intraventricular infusion of morphine for intractable pain in cancer of the head and neck. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:404-408.

46 Karavelis A, Foroglou G, Selviaridis P, et al. Intraventricular administration of morphine for control of intractable cancer pain in 90 patients. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:57-62.

47 Tasker RR. Stereotactic surgery. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of Pain. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1994:1137-1158.

48 Hardy RWJr, Bay JW. Surgery of the sympathetic nervous system. In: Schmidek HH, Sweet WH, editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995:1637-1646.

49 De Salles A, Johnson JP. Sympathectomy for pain. In: Winn HR, editor. Youmans Neurological Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:3093-3105.

50 Johnson JP, Obasi C, Hahn MS, et al. Endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy. J Neurosurg (1 suppl). 1999;91:90-97.

51 Schwartzman RJ, Liu JE, Smullens SN, et al. Long-term outcome following sympathectomy for complex regional pain syndrome type I (RSD). J Neurol Sci. 1997;150:149-152.

52 Mailis A, Furlan A. Sympathectomy for pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD002918.

53 Burchiel KJ, Johans TJ, Ochoa J. The surgical treatment of painful traumatic neuromas. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:714-719.

54 Van Eerten PV, Polder TW, Broere CAJ. Operative treatment of meralgia paresthetica: transection versus neurolysis. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:63-65.

55 Starling JR, Harms BA. Diagnosis and treatment of genitofemoral and ilioinguinal neuralgia. World J Surg. 1989;13:586-591.

56 Kim DH, Murovic JA, Kline DG. Surgical management of 33 ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgias at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1012-1020.

57 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, et al. Percutaneous radio-frequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1721-1726.

58 Hosobuchi Y. The majority of unmyelinated afferent axons in human ventral roots probably conduct pain. Pain. 1980;8:167-180.

59 Onofrio BM, Campa HK. Evaluation of rhizotomy: review of 12 years’ experience. J Neurosurg. 1972;36:751-755.

60 North RB, Kidd DH, Campbell JN, et al. Dorsal root ganglionectomy for failed back surgery syndrome: a 5-year follow-up study. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:236-242.

61 Acar F, Miller J, Golshani KJ, et al. Pain relief after cervical ganglionectomy (C2 and C3) for the treatment of medically intractable occipital neuralgia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2008;86:106-112.

62 North RB, Kidd DH, Zahurak M, et al. Specificity of diagnostic nerve blocks: a prospective, randomized study of sciatica due to lumbosacral spine disease. Pain. 1996;65:77-85.

63 Taha JM, Favre J, Burchiel KM, Grossman RG, Loftus CM, editors. Principles of Neurosurgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven. 1999:435-442.

64 Saris SC, Silver JM, Vieira JFS, et al. Sacrococcygeal rhizotomy for perineal pain. Neurosurgery. 1986;19:789-793.

65 Tew JMJr, Taha JM. Percutaneous rhizotomy in the treatment of intractable facial pain (trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, and vagal nerves). In: Schmidek HH, Sweet WH, editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995:1469-1484.

66 Rath SA, Seitz K, Soliman N, et al. DREZ coagulations for deafferentation pain related to spinal and peripheral nerve lesions: indication and results of 79 consecutive procedures. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1997;68:161-167.

67 Nashold JRB, Nashold BSJr. Microsurgical DREZotomy in treatment of deafferentation pain. In: Schmidek HH, Sweet WH, editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995:1623-1636.

68 Sindou MP. Microsurgical DREZotomy. In: Schmidek HH, Sweet WH, editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995:1613-1621.

69 Sindou M, Mertens P, Wael M. Microsurgical DREZotomy for pain due to spinal cord and/or cauda equine injuries: long-term results in a series of 44 patients. Pain. 2001;92:159-171.

70 Kanpolat Y, Tuna H, Bozkurt M, et al. Spinal and nucleus caudalis dorsal root entry zone operations for chronic pain. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(suppl 1):235-242.

71 Bullard DE, Nashold BSJr. The caudalis DREZ for facial pain. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1997;68:168-174.

72 Gorecki JP, Nashold BS. The Duke experience with the nucleus caudalis DREZ operation. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1995;64:128-131.

73 Poletti CE. Open cordotomy and medullary tractotomy. In: Schmidek HH, Sweet WH, editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995:1557-1571.

74 Nagaro T, Adachi N, Tabo E, et al. New pain following cordotomy: clinical features, mechanisms, and clinical importance. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:425-431.

75 Jones B, Finlay I, Ray A, et al. Is there still a role for open cordotomy in cancer pain management? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:179-184.

76 Tasker RR. Percutaneous cordotomy. In: Schmidek HH, Sweet WH, editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995:1595-1611.

77 Crul BJ, Blok LM, van Egmond J, et al. The present role of percutaneous cervical cordotomy for the treatment of cancer pain. J Headache Pain. 2005;6:24-29.

78 Kanpolat Y. Percutaneous destructive pain procedures on the upper spinal cord and brainstem in cancer pain: CT-guided techniques, indications, and results. Adv Stand Neurosurg. 2007;32:147-173.

79 Jannetta PJ, Gildenberg PL, Loeser JD, et al. Operations on the brain and brain stem for chronic pain. In: Bonica JJ, editor. The Management of Pain. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1990:2082-2103.

80 Rosomoff HL, Papo I, Loeser JD, et al. Neurosurgical operations on the spinal cord. In: Bonica JJ, editor. The Management of Pain. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1990:2067-2081.

81 Watling CJ, Payne R, Allen RR, et al. Commissural myelotomy for intractable cancer pain: report of two cases. Clin J Pain. 1996;12:151-156.

82 Hitchcock ER. Stereotactic cervical myelotomy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1970;33:224-230.

83 King RB. Anterior commissurotomy for intractable pain. J Neurosurg. 1977;47:7-11.

84 Gildenberg PL. Myelotomy through the years. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2001;77:169-171.

85 Hirshberg RM, Al-Chaer ED, Lawand NB, et al. Is there a pathway in the posterior funiculus that signals visceral pain? Pain. 1996;67:291-305.

86 Gybels JM, Sweet WH. Neurosurgical Treatment of Persistent Pain: Physiological and Pathological Mechanisms of Human Pain. Basel: Karger; 1989.

87 Nauta HJW, Hewitt E, Westlund KN, et al. Surgical interruption of a midline dorsal column visceral pain pathway. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:538-542.

88 Gildenberg PL. Brainstem procedures for management of pain. In: Winn HR, editor. Youmans Neurological Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:3073-3083.

89 Fountas KN, Lane FJ, Jenkins PD, et al. MR-based stereotactic mesencephalic tractotomy. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2004;82:230-234.

90 Tasker RR. Intracranial ablative procedures for pain. In: Tindall TG, Cooper PR, Barrow DL, editors. The Practice of Neurosurgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:3115-3128.

91 Tasker RR. Thalamic stereotaxic procedures. In: Schaltenbrand G, Walker AE, editors. Stereotaxy of the Human Brain: Anatomical, Physiological and Clinical Applications. Stuttgart, Germany: Georg Thieme Verlag; 1982:484-497.

92 Tasker RR. Thalamotomy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1990;1:841-864.

93 Young RF, Vermeulen SS, Grimm P, et al. Gamma knife thalamotomy for the treatment of persistent pain. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1995;64(suppl 1):172-181.

94 Young RF. Radiosurgery for pain management. In: Follett KA, editor. Neurosurgical Pain Management. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:237-244.

95 Hassenbusch SJ, Pillay PK, Barnett GH. Radiofrequency cingulotomy for intractable cancer pain using stereotaxis guided by magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:220-223.

96 Bouckoms AJ. Limbic surgery for pain. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of Pain. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1994:1171-1187.

97 Yen CP, Kung SS, Su YF, et al. Stereotactic bilateral anterior cingulotomy of intractable pain. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:886-890.

98 Wilkinson HA, Davidson KM, Davidson RI. Bilateral anterior cingulotomy of chronic noncancer pain. Neurosurgery. 1999;46:1129-1134.

99 Levin AB, Katz J, Benson RC, et al. Treatment of pain of diffuse metastatic cancer by stereotactic chemical hypophysectomy: long term results and observations on mechanism of action. Neurosurgery. 1980;6:258-262.

100 Ramirez LF, Levin AB. Pain relief after hypophysectomy. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:499-504.

101 Hayashi M, Taira T, Chernov M, et al. Role of pituitary radiosurgery for the management of intractable pain and potential future applications. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2003;81:75-83.