CHAPTER 119 NEUROLOGY OF RHEUMATOLOGY, IMMUNOLOGY, AND TRANSPLANTATION

Evaluation of patients with rheumatic, inflammatory, or post-transplantation neurological syndromes is challenging because these patients can have a wide variety of disease-specific neurological pathological processes, adverse effects of medications, or, if they have been immunosuppressed, opportunistic infections. They often need a thorough evaluation that might include characterizing the activity of their systemic illness, imaging of brain or spinal cord, electrodiagnostic studies, and spinal fluid examination.

PRIMARY SJÖGREN’S SYNDROME

Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disease that affects exocrine glands and has protean neurological effects.1 The sicca syndrome of dry eyes and dry mouth is its signature characteristic, but other systemic manifestations include arthralgias and myalgias, fatigue, and weight loss. Sjögren’s syndrome can affect the lungs, kidneys, and thyroid; can cause small- or medium-vessel vasculitis; and can have hematological manifestations, such as anemia, lymphoma, neutropenia, and monoclonal gammopathy. The diagnosis is supported by objective evidence of sicca syndrome, such as positive results of Schirmer’s test for tear production, findings from lip biopsy, and the presence of specific autoantibodies (anti-Ro [SSA] and anti-La [SSB]). Sjögren’s syndrome can be associated with other inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, in which case it is termed secondary Sjögren’s syndrome. The neurological aspects discussed as follows are associated with primary Sjögren’s syndrome.

Central Nervous System Manifestations

Mild deficits on psychometric testing are the most common cerebral abnormalities in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. In rare cases, the neuropsychological impairment is severe enough to cause dementia. Deficits are sometimes correlated with specific areas of brain hypoperfusion, demonstrable with techniques such as single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), even in patients who have normal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans and no other manifestations of central nervous system (CNS) disease.2

Peripheral Nervous System Manifestations

Symmetrical length-dependent neuropathy is the most common peripheral nervous system finding in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and can be the presenting clinical finding. Manifestations include small- or mixed-fiber sensory axonal neuropathy or sensorimotor neuropathies. Motor neuropathies resembling Guillain-Barré syndrome or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy are infrequent. Clinical peripheral nervous system disease probably occurs in 10% to 20% of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome; a higher incidence of peripheral nerve abnormalities is noted among patients with Sjögren’s syndrome who are carefully screened with quantitative sensory and electrodiagnostic testing. Conversely, if patients with idiopathic axonal neuropathies are screened for Sjögren’s syndrome, a few meet definite diagnostic criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome, and more have isolated features of Sjögren’s syndrome, such as symptoms of sicca syndrome or a positive findings on lip biopsy.3 Most patients with peripheral neuropathy and sicca syndrome do not eventually develop other extraglandular manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome.4

Nerve biopsy findings in patients with peripheral neuropathy and Sjögren’s syndrome are generally no more specific than those in other axonal neuropathies. Nonspecific epineurial inflammatory cells are often present, but there is rarely definite evidence of vasculitis.4

Information on neurological responses to treatment is limited to uncontrolled observations in small series of patients. Steroids are rarely helpful in patients with axonal polyneuropathies.1 The neuronopathy is poorly responsive to steroids or immunosuppression.5,6 Myelopathy and other CNS syndromes are more likely to improve with steroid treatment. In patients with severe myelopathy or mononeuritis multiplex, cyclophosphamide in combination with steroid therapy sometimes yields apparent benefit.1 Case reports suggest improvement in myelopathy treated with steroids and azathioprine or chlorambucil or in sensory neuronopathy treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. Responses to plasmapheresis have been mixed.7 A least one patient experienced improvement after treatment with the anti–tumor necrosis factor antibody infliximab.8

PROGRESSIVE SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

Neurological complications are relatively limited in patients with progressive systemic sclerosis. These include headache, myopathy, trigeminal neuropathy, peripheral neuropathy, autonomic neuropathy, ectopic calcifications, and stroke.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Atlantoaxial Disease

Rheumatoid arthritis can affect the cervical spine, where ligamentous inflammatory changes lead, in particular, to atlantoaxial joint subluxation (Fig. 119-1). Subluxation is usually anterior but can also occur vertically, laterally, or posteriorly. Anterior atlantoaxial subluxation was found in fewer than 3% of patients who had had rheumatoid arthritis for less than 5 years, 15% of those who had had the disease for 10 to 15 years, and 26% of those who had had the disease for more than 15 years.9 Once present, the subluxation may not increase; however, in a decade, at least 25% of those with subluxation have progression in subluxation, varying from 1 to 7 mm.

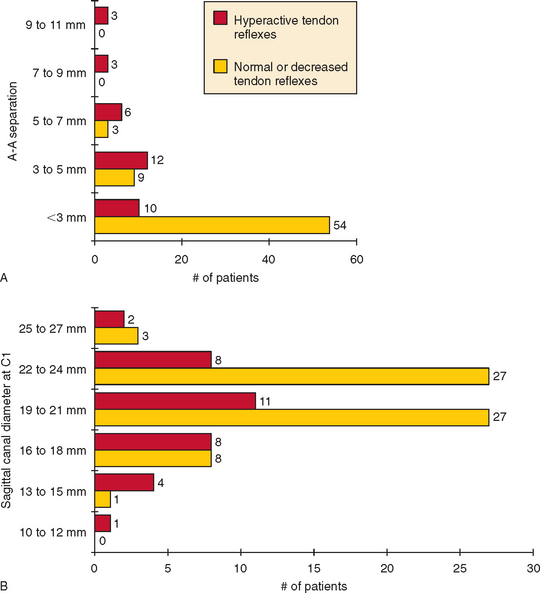

Atlantoaxial subluxation is usually asymptomatic but can cause spinal cord compression. As compression worsens, signs of myelopathy, including sphincter disturbance, sensory deficits, extensor plantar responses, or weakness in legs or all extremities, can evolve. The risk of myelopathy increases as the atlantoaxial separation in flexion increases and as the diameter of the spinal canal at the C1 level decreases (Fig. 119-2). Soft tissue pannus, vascular compromise, and intermittent spinal cord compression during neck movement also influence the degree of myelopathy. The myelopathy usually evolves insidiously but can worsen suddenly. Arm and leg weakness is more common than weakness limited to the legs. Patients typically also have sensory findings, spasticity, sphincter dysfunction, and extensor plantar responses.

The indications for surgery for atlantoaxial subluxation rely more on clinical signs of myelopathy or brainstem compression than on the measured extent of the subluxation. Spontaneous odontoid fracture is another indication for surgery. Among patients undergoing surgery, most do not regain lost neurological functions, but the subluxed segment is stabilized and progressive neurological deterioration is avoided.

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune inflammatory disease that affects many organ systems. The American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for SLE10 require for diagnosis that a patient have any 4 of 11 criteria: malar rash, discoid rash, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, arthritis, serositis, renal disease, neurological disorder, hematological disease, immunological changes, and antinuclear antibodies. SLE most commonly affects young women.

Neurological manifestations of SLE take many forms (Table 119-1). A patient with SLE can have more than one of the syndromes. Each syndrome might have causes other than lupus, and so the diagnosis of neuropsychiatric lupus requires the presence of one of these neurological syndromes; the systemic diagnosis of SLE is based on other data, such as the American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria for SLE, and exclusion of alternative diagnoses. For example, the identification of a case of meningitis as lupus-related aseptic meningitis rests on establishing the diagnosis of SLE; ruling out infectious causes of meningitis, especially opportunistic infections; and ruling out drug-induced meningitis, such as that caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

TABLE 119-1 American College of Rheumatology Classification of Neuropsychiatric Syndromes Observed in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

| Central Nervous System | Peripheral Nervous System |

|---|---|

| Aseptic meningitis | Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy |

| Cerebrovascular disease | Autonomic disorder |

| Demyelinating disease | Mononeuropathy, single or multiplex |

| Headache | Myasthenia gravis |

| Movement disorder (chorea) | Cranial neuropathy |

| Myelopathy | Plexopathy |

| Seizure disorder | Polyneuropathy |

| Acute confusional state | |

| Anxiety disorder | |

| Cognitive dysfunction | |

| Mood disorder | |

| Psychosis |

From The American College of Rheumatology nomenclature and case definitions of neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42:599-608.

Central Nervous System Manifestations

Headache

Headaches, including tension headache, migraine with aura, and migraine without aura, are more common in patients with SLE than in matched controls.11 These headaches are not necessarily evidence of active inflammatory disease. However, other causes of headache, such as pseudotumor cerebri or meningitis, merit consideration before the headache is attributed to common benign categories.

Myelopathy

Acute myelitis occurs in perhaps 1% of patients with SLE; this rate is higher than the prevalence of myelitis in the general population.12 Patients may have paraparesis or quadriparesis; bilateral sensory dysfunction, often to a thoracic level; and sphincter dysfunction. At times, posterior column function is relatively preserved. T2-weighted MRI of the spinal cord often reveals an area of hyperintensity within the cord. MRI evidence of continuous abnormality over multiple spinal segments is more indicative of a systemic inflammatory cause of myelitis, such as SLE or Sjögren’s syndrome, than of viral infection or multiple sclerosis. Even when the MRI is normal, it allows exclusion of alternative diagnoses such as cord compression by fracture, subluxation, epidural abscess or hemorrhage, or epidural lipomatosis. Spinal fluid studies in patients with acute myelitis often reveal mild pleocytosis and protein level elevation. An occasional patient appears to have an anterior spinal artery infarction or vasculitis within the spinal cord, but pathological findings are inconsistent. Patients with lupus and myelitis have an increased incidence of antiphospholipid antibodies. Lacking controlled treatment trials, many clinicians routinely treat the myelitis with high-dose steroids, such as 1 g of methylprednisolone daily for 3 days or more. Other options include cyclophosphamide and plasmapheresis. A retrospective literature review demonstrated complete recovery in 50% of cases, partial recovery in 29%, and no recovery in 21%.

Seizure Disorder

Seizures occur in more than 10% of patients with SLE, a rate well above the prevalence in the general population.13 In some patients, particularly those who have had strokes or focal cerebritis, the seizures are secondary to focal brain lesions. Patients with antiphospholipid antibodies are more likely to have seizures. In other patients, the seizures are associated with systemic or metabolic abnormalities, such as hypertensive encephalopathy, uremia, infections, or electrolyte abnormalities.

Cognitive Dysfunction

Subtle cognitive dysfunction is the most common neuropsychiatric abnormality in patients with SLE, affecting as many as 80% of patients. If less sensitive psychometric measures are used, the prevalence of cognitive impairment can still exceed 20%. Cognitive dysfunction often occurs without overt evidence of strokes or focal brain lesions. Cognitive abnormalities often fluctuate over months, and the prevalence can decrease over time.14 However, cognition can deteriorate progressively, especially in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies, chronic prednisone use, diabetes, depression, and less education.15 Chronic aspirin use is correlated with better longterm cognitive status.

Psychosis and Acute Confusional State

In a small percentage of patients with SLE, episodes of acute psychosis develop. The psychosis can arise de novo or be provoked by initiation of or increase in corticosteroid therapy. Patients with hypoalbuminemia seem to be at increased risk for steroid-induced psychosis.16 When the psychosis is not attributable to steroids, high-dose steroids are often therapeutic. Reports of an association between autoantibodies to ribosomal P and psychosis have not been consistently confirmed.

Neuroimaging

Brain imaging abnormalities by computed tomography, MRI, or SPECT are common in patients with SLE. Findings of focal cerebral ischemia are usually correlated with clinical episodes of stroke but are occasionally seen in patients with lupus who do not have clinical evidence of neuropsychiatric syndromes. Bright lesions on MRI sequences such as fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging, proton density sequences, or T2-weighted sequences, particularly in periventricular or subcortical white matter, are also seen in patients with lupus who have no known neuropsychiatric disease and are even more common in those with CNS symptoms. SPECT frequently reveals areas of focal hypoperfusion in patients with lupus, regardless of whether they have clinical CNS disease.17

Peripheral Nervous System Manifestations

Cranial Nerves III to XII

When patients with SLE develop cranial nerve dysfunction, they must be evaluated for brainstem causes and for ancillary causes such as infectious basilar meningitis. For example, abnormal eye movements can develop by many different mechanisms (Table 119-2). In addition, patients with lupus can develop idiopathic neuropathy of almost any cranial nerve, most frequently the facial nerve, affected in 0.5% of these patients in one clinical series.

TABLE 119-2 Examples of Neuro-ophthalmoplegic Findings in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Adapted from Rosenbaum RB, Campbell SM, Rosenbaum JT: Clinical Neurology of Rheumatic Diseases. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1996.

Polyneuropathy

Symmetrical, length-dependent sensory or sensorimotor neuropathy is the most common peripheral nervous system manifestation of SLE, occurring in approximately 20% of patients. The neuropathy is usually mild, chronic, and slowly progressive and rarely warrants nerve biopsy. Biopsy findings are usually those of axonal destruction, often accompanied by epineurial vasculitis. In the setting of known lupus, this histological vasculitis is not an indication for more aggressive immunosuppression unless the neuropathy itself is aggressive or the patient has other evidence of lupus activity.

ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION

In patients who have undergone organ transplantation, neurological evaluation and treatment is additionally complex.18 Ten percent or more have neurological complications. Before transplantation, the patients often have encephalopathy or neuromuscular disease related to underlying disease organ failure. Neurological complications of renal failure, hepatic failure, cardiopulmonary failure, and malignancy are covered in elsewhere in this book. In addition, liver, kidney, or other organ failure can induce metabolic derangements or lead to drug toxicities related to defective drug metabolism.

Acute Postoperative Encephalopathy (Coma, Failure to Awaken)

Immunosuppressive drugs can have direct neurological toxicity (Table 119-3) or predispose to opportunistic CNS infections.

TABLE 119-3 Some Neurological Adverse Effects of Anti-inflammatory and Immunosuppressant Drugs

| Drug | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|

| Antimalarials (chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine) | Headache, mental status changes, seizures, impaired accommodation, scotomata, retinopathy, hearing loss, vestibulopathy, movement disorder, peripheral neuropathy, vacuolar myopathy, myasthenic syndrome |

| Azathioprine | Aseptic meningitis, seizures |

| Colchicine | Peripheral neuropathy, myopathy |

| Corticosteroids | Myopathy, psychosis, seizures, depression or mania, epidural lipomatosis |

| Cyclosporine, tacrolimus | Tremor, leukoencephalopathy, seizures, encephalopathy, hallucinations, akinetic mutism, paresthesias, dysesthesia, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, TTP |

| Gold | Peripheral neuropathy |

| IVIg | Aseptic meningitis, headache, stroke |

| Methotrexate | Encephalopathy (at high doses) |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Aseptic meningitis, seizures, encephalopathy, hearing loss, vestibulopathy |

| OKT3 monoclonal antibodies | Headache, aseptic meningitis, encephalopathy (myoclonus, seizures, psychosis) |

| Penicillamine | Inflammatory myopathy, myasthenia |

| Sulfasalazine | Aseptic meningitis, seizures, encephalopathy |

IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulin; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Central pontine myelinolysis is another potential cause of coma or disturbed consciousness in patients in the acute postoperative period. Corticospinal and cranial nerve dysfunction can lead to quadriparesis, pseudobulbar palsy, and impaired eye movements, so that full assessment of consciousness can be difficult. Central pontine myelinolysis is most common after liver transplantation and is often but not invariably tied to rapid correction of hyponatremia. Acute demyelination may not be limited to the pons and can include other white matter sites such as the external and extreme capsules.

An acute encephalopathy, with manifestations such as headache, altered mental status, seizures, or coma, accompanying renal graft rejection, was described in the early 1980s.19 It is not easily explained by changes in blood pressure, medication toxicity, or electrolyte changes. It is more common when rejection is more severe and improves concomitantly with steroid therapy of the rejection episode.19 This syndrome has been neither reported in relation to nonrenal transplants nor examined in more detail in more recent series.

Seizures

Seizures affect between 2% and 40% of transplant recipients, particularly recipients of hearts or livers. The risk of seizures is highest in the first few days after transplantation. A common cause of seizures is toxicity of immunosuppressive drugs, especially cyclosporine, tacrolimus, or OKT3. Cyclosporine-associated seizures are more common in patients who also have hypomagnesemia, hypocholesterolemia, hypertension, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, total body irradiation, or treatment with busulfan and cyclophosphamide (see Wijdiks, 1999, p. 117).18 Seizures can also be caused by myriad metabolic possibilities, including low or high levels of sodium, calcium, or glucose and hepatic or renal failure. A number of drugs can cause seizures (Table 119-4), especially if drug levels are increased as a result of renal failure. Transplant recipients who suffer seizures must be evaluated for structural brain lesions such as ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes, cerebral vein thrombosis, opportunistic CNS infections, or posthypoxic encephalopathy. When seizures occur late after transplantation, metabolic causes are less common, but de novo malignancies and intracranial spread of malignancies (especially in patients who have undergone bone marrow transplantation for leukemia or lymphoma) must be considered.

TABLE 119-4 Examples of Drugs That May Cause Seizures in Transplant Recipients

Adapted from Wijdicks EFM, ed: Neurologic Complications in Organ Transplant Recipients. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1999, p 120.

Opportunistic Infections

Chronic cryptococcal meningitis affects perhaps 1% to 2% of transplant recipients and is diagnosed an average of 2 years after transplantation, especially in patients who still require two or more immunosuppressant drugs. The risk is higher after heart or small bowel transplantation. Focal brain lesions are a much less common manifestation. The rate of mortality from cryptococcal meningitis in transplant recipients approaches 50%.20 The differential diagnosis of chronic meningitis in transplant recipients includes other entities such mycobacterial infections, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis.

Brain abscess occurs in fewer than 1% of transplant recipients. Although Aspergillus is by far the most common organism, many other organisms bear consideration, including Candida, Mucorales, Toxoplasma, and Nocardia. The risk of pyogenic abscess is not increased in these patients. The abscess risk is higher in recipients of heart or heart-lung transplants. The rate of mortality among transplant recipients with brain abscess is more than 80%.21

The most common cause of acute meningitis in transplant recipients is Listeria infection. Another important cause of acute meningitis is Strongyloides stercoralis. In persons from endemic areas of the southern United States, Latin America, or Southeast Asia, the nematode S. stercoralis is a common asymptomatic colonizer of the gut. In immunosuppressed patients, the larvae can infect and penetrate the gut wall, not only spreading themselves but also promoting gram-negative infections. The result can be acute gram-negative bacterial meningitis or eosinophilic meningitis caused directly by the nematode.

Immunosuppressed patients can also develop progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

Strokes

Ischemic infarction of the distal spinal cord can occur if cord blood flow is disturbed during renal transplantation.22

Neuropathy

A few patients develop Guillain-Barré syndrome or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy days or months after bone marrow or solid organ transplantation. Almost all these patients are immunosuppressed, and they usually have serological evidence of cytomegalovirus infection. Treatment is with intravenous immunoglobulin or plasmapheresis, just as for inflammatory demyelinating neuropathies in patients not undergoing transplantation.23 In cases associated with graft-versus-host disease or episodes of transplant rejection, more aggressive immunosuppression can help with both the neuropathy and transplant-associated immunological crisis.

GRAFT-VERSUS-HOST DISEASE

Chronic graft-versus-host disease is a multiorgan inflammatory complication of bone marrow transplantation that develops 3 months or more after transplantation and affects between one third and two thirds of transplant recipients. The skin and liver are the organs most frequently affected. Findings can be similar to those of other autoimmune disorders, including scleroderma or eosinophilic fasciitis, esophageal disease, sicca syndrome, and biliary cirrhosis. Laboratory changes can include lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and antinuclear antibodies. Neurological complications include inflammatory muscle disease similar to polymyositis with findings such as proximal weakness; elevated creatine kinase level; electromyographically evident small, short, easily recruited motor unit potentials sometimes accompanied by fibrillations; and myositic changes evident on muscle biopsy. The myositis is clinically evident in fewer than 1% of patients with graft-versus-host disease.24 The myositis has been successfully treated with immunosuppressive drugs, including prednisone, azathioprine, and cyclosporine. Myasthenia gravis with classical clinical findings and presence of antiacetylcholine receptor antibodies is an even less common accompaniment of graft-versus-host disease.

SUMMARY

Brey RL, Holliday SL, Saklad AR, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes in lupus: prevalence using standardized definitions. Neurology. 2002;58:1214-1220.

Delalande S, de Seze J, Fauchais A-L, et al. Neurologic manifestations in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. A study of 82 patients. Medicine. 2004;83:280-291.

McLaurin EY, Holliday SL, Williams P, et al. Predictors of cognitive dysfunction in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Neurology. 2005;64:297-303.

Rosenbaum RB, Campbell SM, Rosenbaum JT. Clinical Neurology of Rheumatic Diseases. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1996.

Wijdicks EFM, editor. Neurologic Complications in Organ Transplant Recipients. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1999.

1 Delalande S, de Seze J, Fauchais A-L, et al. Neurologic manifestations in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. A study of 82 patients. Medicine. 2004;83:280-291.

2 Belin C, Moroni C, Caillat-Vigneron N, et al. Central nervous system involvement in Sjögren’s syndrome: evidence from neuropsychological testing and HMPAO-SPECT. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 1999;150:598-604.

3 Gorson KC, Ropper AH. Positive salivary gland biopsy, Sjögren syndrome, and neuropathy: clinical implications. Muscle Nerve. 2003;28:553-560.

4 Grant IA, Hunder GG, Homburger HA, et al. Peripheral neuropathy associated with sicca complex. Neurology. 1997;48:855-962.

5 Griffin JW, Cornblath DR, Alexander E, et al. Ataxic sensory neuropathy and dorsal root ganglionitis associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:304-315.

6 Font J, Ramos-Casals M, de la Red G, et al. Pure sensory neuropathy in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Longterm prospective follow-up and review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1552-1557.

7 Chen W-H, Yeh J-H, Chiu H-C. Plasmapheresis in the treatment of ataxic sensory neuropathy associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur Neurol. 2001;45:270-274.

8 Caroyer J-M, Manto MU, Steinfeld SD. Severe sensory neuronopathy responsive to infliximab in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Neurology. 2002;59:1113-1114.

9 Naranjo A, Carmona L, Gavrila D, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of anterior atlantoaxial luxation in a nation-wide sample of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:427-432.

10 The American College of Rheumatology nomenclature and case definitions of neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:599-608.

11 Ainiala H, Hietaharju A, Loukkola J, et al. Validity of the new American College of Rheumatology criteria for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes: a population-based evaluation. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45:419-423.

12 Kovacs B, Lafferty TL, Brent LH, et al. Transverse myelopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: an analysis of 14 cases and review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:120-124.

13 Appenzeller S, Cendes F, Costallat LTL. Epileptic seizures in systemic lupus erythematosus. Neurology. 2004;63:1808-1812.

14 Hanly JG, Hong C, Smith S, et al. A prospective analysis of cognitive function and anticardiolipin antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:728-734.

15 McLaurin EY, Holliday SL, Williams P, et al. Predictors of cognitive dysfunction in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Neurology. 2005;64:297-303.

16 Brey RL, Holliday SL, Saklad AR, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes in lupus. Prevalence using standardized definitions. Neurology. 2002;58:1214-1220.

17 Sabbadini MG, Manfredi AA, Bozzolo E, et al. Central nervous system involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus patients without overt neuropsychiatric manifestations. Lupus. 1999;8:11-19.

18 Wijdicks EFM, editor. Neurologic Complications in Organ Transplant Recipients. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1999.

19 Gross MLP, Sweny P, Pearson RM, et al. Rejection encephalopathy. An acute neurological syndrome complicating renal transplantation. J Neurol Sci. 1982;56:23-34.

20 Wu G, Vilchez RA, Eidelman B, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: an analysis among 5,521 consecutive organ transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2002;4:183-188.

21 Selby R, Ramirez CB, Singh R, et al. Brain abscess in solid organ transplant recipients. Arch Surg. 1997;132:304-310.

22 Jablecki CK, Aguilo JJ, Piepgras DG, et al. Paraparesis after renal transplantation. Ann Neurol. 1977;2:154-155.

23 El-Sabrout RA, Radovancevic B, Ankoma-Sey V, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome after solid organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;71:1311-1316.

24 Stevens AM, Sullivan KM, Nelson JL. Polymyositis as a manifestation of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Rheumatoloy (Oxford). 2003;42:34-39.