CHAPTER 121 NEUROLOGY OF CEREBRAL PALSY

CLASSIFICATION AND CLINICAL FEATURES

The term cerebral palsy is not a diagnosis, nor does its use denote a specific etiology or degree of severity. The term defines a condition whose cause is no longer active and that occurred during brain development. The cerebral palsies are a heterogeneous group of clinical syndromes that are characterized by motor and postural dysfunction caused by a nonprogressive lesion in the developing brain. Although the disorder itself is nonprogressive, the appearance of neuropathological lesions and their clinical expression change over time as the brain matures.1

Classification of the cerebral palsy syndromes is based on the type and distribution of the motor abnormality (Table 121-1). An overlap of findings can occur, but the principal features are usually evident by age 5 years. Patients with a spastic syndrome have the features of an upper motor neuron syndrome. These include the positive signs of spastic hypertonia, hyperreflexia, extensor plantar responses, clonus, and contractures. Negative signs include slow, effortful, uncoordinated voluntary movements; poor fine motor function; difficulty isolating individual movements; and fatigability. The spastic syndromes are subdivided according to the distribution of abnormal signs. In spastic diplegia, the legs are more affected than the arms. In spastic quadriplegia, the arms are involved equally or more than the legs, and in hemiplegia, one side of the body is involved.

From Miller G: Cerebral palsies: an overview. In Miller G, Clark GD, eds: The Cerebral Palsies. Causes, Consequences, and Management. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998, pp 1-36.

Dyskinetic signs may be found in all the spastic syndromes. Spastic diplegia can occur in both full-term and preterm infants, but it is associated particularly with prematurity, the risk increasing with the degree of prematurity, and is often associated with periventricular leukomalacia and ventriculomegaly. Patients with mild leukomalacia have relatively good hand function and fewer associated disabilities. Those with more severe involvement have compromised hand function, contractures, cortical sensory impairment, and involuntary movements and are more likely to have strabismus and visual impairment. Poor growth, particularly below the waist, is usually present. Asymmetrical diplegia, which can be found in preterm infants after unilateral hemorrhagic infarction, is associated with more severe disabilities than is symmetrical spastic diplegia. Spastic hemiplegia typically affects full-term infants of normal birth weight and may be caused by prenatal cerebrovascular events, neonatal stroke, or cerebral dysgenesis. Postnatal causes include arterial and venous stroke, trauma, infection, and vasculopathies.2 The condition may be missed during early infancy without careful examination and may manifest later as early hand dominance and reduced movement or abnormal posturing on one side. A focal seizure, or a secondarily generalized one, may be the first indication of its presence. The typical hemiplegic gait is noted when the child begins to walk or run; walking and running usually begin within the normal age range, or are only mildly delayed, unless marked mental retardation is present. In general, frank disorders of language are related more closely to cognitive abilities than to the side of the lesion. Cortical sensory deficits on the affected side are correlated with poor growth, although not with the severity of the motor deficit.3 Spastic quadriplegia1 is the most severe form of spastic cerebral palsy. Causes include prenatal infection or cerebral dysgenesis occurring in full-term infants who are small for gestational age, severe perinatal or postnatal diffuse brain insults, and extreme prematurity.

Common associated features include marked mental retardation, profound motor disability, dysarthria or anarthria, seizures, hip deformity, scoliosis, and limb contractures. Sensory impairment, in particular visual, may be present, in addition to microcephaly. The dyskinetic cerebral palsy syndromes1 typically affect full-term infants and can follow severe acute full-term perinatal asphyxia because of selective basal ganglia damage and status marmoratus.4 These syndromes are divided into two types: mainly athetoid, in which the abnormal movements are a combination of athetosis and chorea, and mainly dystonic. Dysarthria and oropharyngeal difficulties are present in conjunction with facial grimacing. Retained primitive reflexes are a feature. Emotion, change in posture, or intended movement may worsen or induce the abnormal movements. Those with the mainly dystonic form tend to be more severely disabled, with anarthria and poor feeding, and are unable to ambulate. Manifestation in early infancy is with delayed psychomotor development, decreased tone, drooling, grimacing, and abnormal retention of primitive reflexes. The involuntary movements develop with time and may not be clearly apparent until ages 2 to 3 years. Contractures usually do not develop unless they are positional. Patients with ataxic cerebral palsy usually are born at term, and most cases are caused by early prenatal events,1 including genetic causes.5 They manifest with congenital hypotonia and delayed language and gross motor skills. The development of speech, which is typically slow, jerky, and explosive, is related to intellectual ability. The ataxia usually improves with age. The diagnosis is made by exclusion, with the recognition that all patients with cerebral palsy have some degree of incoordination and disturbed posture. The condition should also be distinguished from metabolic and degenerative disorders, which may manifest with some of the same features.

ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

Other disorders of brain function frequently accompany the motor abnormalities that characterize cerebral palsy.6 These include mental retardation, epilepsy, and abnormalities of vision, hearing, language, cortical sensation, attention, learning, and behavior. Dyspraxias and agnosias may interfere with skilled tasks, independently from the severity of gross motor dysfunction. Mental retardation often, but not always, is correlated with the severity of motor handicap, and patients with atonic cerebral palsy or spastic quadriplegia are the most severely affected. Seizures are also most common in atonic cerebral palsy and spastic quadriplegia, in addition to acquired hemiplegia, and least common in mild symmetrical spastic diplegia and mainly athetoid cerebral palsy.1 Ocular and visual abnormalities are common and include refractive error, strabismus, amblyopia, field defects, cortical visual impairment, and eye movement abnormalities. Disorders of speech and language are frequent and often complex, and it is important to assess for hearing loss. Although failure to thrive and poor nutrition may be related to nonnutritional factors, poor nutrition often plays a significant role in the severity of cerebral palsy and can be combated by the early use of a gastrostomy.7 Palatopharyngeal incoordination and gastroesophageal reflux contribute to chronic respiratory disease in patients with severe cerebral palsy, and this is further worsened by respiratory muscle incoordination, chest deformity, and sleep apnea. Immobile patients are at risk for osteopenia and fractures, and orthopedic disorders, including hip dislocation and scoliosis, are common. Although the primary neuropathological lesion is static, neurological signs may change or worsen with increasing age.8 However, sometimes the changes are caused by a spondylotic myelopathy. Drug reactions may also be cause of new or worsening neurological signs: for example, they may follow intake of carbamazepine or phenytoin.

DIAGNOSIS

Thus, an early history might be poor feeding and sleeping in a young infant, who is often irritable, is visually inattentive, arches when handled, and has poor head control when pulled to a sitting position. Examination includes an evaluation of posture and tone in prone and supine positions, when pulled to sit, in supported sitting, and in ventral and vertical suspension. Although abnormal findings are suggestive of an abnormal nervous system, and not necessarily cerebral palsy, in the correct setting the diagnosis can be made after serial evaluation. Similarly, the presence of primitive reflexes such as the tonic neck, tonic labyrinthine, and positive support reflexes might suggest the diagnosis.9 These usually are suppressed between the ages of 3 and 6 months, but if they are maintained or obligatory, this is abnormal. For example, a tonic labyrinthine response can be elicited in the supine position by extending or flexing the neck; extending causes flexion of the limbs, and flexing causes limb extension. An abnormal positive support response, occurring when the baby is held in vertical suspension, is extension of the legs, and weight bearing elicits sustained plantar flexion of the feet. Coordination of the upper limbs is also affected, and a failure to develop a pincer grasp, in conjunction with splaying of the hand when attempting to reach and grasp, may also be observed.

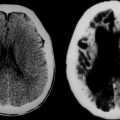

NEUROIMAGING

Magnetic resonance imaging has become a useful diagnostic instrument during the neonatal period. Abnormal signal in the posterior limb of the internal capsule after hypoxic-ischemic injury is correlated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcome,10 as is abnormal appearance on diffusion-weighted imaging.11 In the newborn brain, the imaging sequence most sensitive to injury depends on the timing of the injury. During the first few days, diffusion-weighted imaging is most sensitive, particularly from days 2 through 4. At 1 week, T1- and T2-weighted images are most sensitive.12 Later in life, magnetic resonance imaging can identify a lesion in the majority of cases and can often provide information regarding the timing of the insult.13,14

INVESTIGATIONS

Cerebral palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion. A practice parameter from the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society (Ashwal et al, 2004)14 stressed that it is important to determine that the condition is not progressive or degenerative. Thus, a detailed history and examination are important, in addition to screening for mental retardation, vision and hearing abnormalities, speech and language disorders, and nutrition and feeding. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain is recommended as an aid to determining etiology and prognosis. Metabolic and genetic testing should be performed if the history or findings on neuroimaging do not identify a specific structural abnormality or clear evidence of a diagnosis, or if there are atypical features in the history or examination that might be suggestive of a neurometabolic or neurogenetic disorder.

ETIOLOGY

Cerebral palsy occurs in about 2 per 1000 live births; the rate increases with decreasing gestational age.15 About half the cases occur in infants born at term, and most of these are caused by prenatal factors. Perinatal asphyxia in term infants contributes only a small proportion to the overall numbers.16 Cerebral palsy has been reported in 12% of infants born with a gestational age of less than 27 weeks and in 8% of infants with a birth weight of less than 800g.17 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, in collaboration with the American Academy of Pediatrics (2003), have published criteria for establishing a link between intrapartum events and later cerebral palsy.18 These criteria include (1) evidence of metabolic acidosis in fetal umbilical cord arterial blood at delivery with a pH of less than 7 and a base excess of more than 12 mmol/L, although this by itself is not a useful finding, inasmuch as most newborns with this finding are neurologically normal later; (2) early-onset moderate or severe neonatal encephalopathy in infants of 34 or more weeks’ gestation; (3) a spastic or dyskinetic cerebral palsy; and (4) exclusion of other identifiable etiologies such as trauma, coagulation disorders, infection, or genetic disorders. An intrapartum association may be suggested if there is a sentinel event immediately before or during labor such as a ruptured uterus, placental abruption, umbilical cord prolapse, amniotic fluid embolism, maternal cardiac arrest, or severe hemorrhage. Although abnormal fetal heart rate patterns such as late decelerations and loss of beat-to-beat variability may be present in infants who later develop cerebral palsy, the false-positive rate is 99%. Other findings include evidence of multiple organ damage.

In many children, cerebral palsy is the result of a brain malformation.19 Brain malformations result from abnormal brain development that might affect cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, survival, or synaptogenesis. This could occur as a result of exposure to radiation, teratogens, or infectious agents during a critical period of gestation. Chromosomal abnormalities can be associated with malformations, as can some neurocutaneous syndromes such as hypomelanosis of Ito or the linear sebaceous nevus syndrome with hemimegalencephaly. Many malformations have a known genetic basis. X-linked lissencephaly/subcortical band heterotopia is caused by mutations of the X-linked gene that codes for doublecortin, a microtubule-associated protein. Because of random X-inactivation, affected boys and men have type 1 lissencephaly, and affected girls and women may have the less severe form, characterized by subcortical band heterotopia. The Miller-Dieker syndrome is also associated with type 1 lissencephaly and caused by a microdeletion at locus 17q13.3 that involves the LIS 1 gene product platelet activating factor acetylhydrolase, which is involved in the regulation of microtubules and neuronal migration. Bilateral periventricular nodular heterotopia is an X-linked dominant disorder, lethal in male fetuses, and is caused by a mutation in the filamin 1 gene. Filamin 1 is a cytoskeletal actin-binding protein that plays an important role in cellular movement.

Polymicrogyria is a cortical malformation in which there is an excessive number of small gyri separated by abnormally shallow sulci. The underlying cytoarchitecture is abnormal. Causes are both nongenetic and genetic. Nongenetic causes include infections, such as cytomegalovirus, and inadequate perfusion. Genetic forms20 include the autosomal recessive bilateral frontoparietal polymicrogyria, which is related to mutations in the GPR56 gene on chromosome 16; bilateral perisylvian polymicrogyria, some cases of which are linked to a mutation at locus Xq28; autosomal recessive bilateral generalized polymicrogyria; and possibly sporadic bilateral frontal polymicrogyria and bilateral parasagittal parieto-occipital polymicrogyria. Schizencephaly is a neuronal migration disorder characterized by a unilateral or bilateral cleft, lined with polymicrogyria, extending from the pial surface to the lateral ventricle.21 All these conditions may manifest with seizures and various types of spastic cerebral palsy. Some cases are caused by mutations in the homeobox gene EMX2. Another homeobox gene associated with brain malformations is the ARX gene, located at Xp22.13.22 Abnormal phenotypes include X-linked lissencephaly with ambiguous genitalia, hydranencephaly with ambiguous genitalia, and Partington’s syndrome (mental retardation, dystonic hand movements, dysarthria, and awkward gait).

The risk of cerebral palsy is increased among multiple births, and in utero death of a twin increases the risk.23 Some cases may be caused by an unrecognized fetal death of a twin.24 Perinatal stroke contributes to the etiology of cerebral palsy, particularly spastic hemiplegia. The condition may manifest with a neonatal seizure, or it may not be recognized until later in infancy or early childhood. The stroke is often arterial but can be caused by sinovenous thrombosis. Risk factors include preeclampsia, intrauterine growth retardation, and coagulation abnormalities. The last include decreased levels of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III; increased lipoprotein and homocysteine levels; and genetic factors such as factor V Leiden and factor II mutations.2 Intracranial hemorrhage in a full-term infant may manifest with seizures, abnormal movements, apnea, lethargy, irritability, and a bulging fontanelle.25 Residual germinal matrix may be the source of a thalamic hemorrhage. Predisposing factors for cerebral vein thrombosis, such as sepsis, congenital heart disease, coagulopathy, and electrolyte disturbance, may also be present26.

Infectious causes include congenital infections such as cytomegalovirus, syphilis, varicella, and toxoplasmosis. Chorioamnionitis is associated with cerebral palsy in both full-term and preterm infants27,28 and is thought to be related to increased concentrations of inflammatory mediators, such as interleukins and tumor necrosis factor,29 which are part of an inflammatory response that damages white matter.

Cerebral palsy develops in about 5% to 15% of surviving preterm infants1 and is associated with periventricular leukomalacia, ventriculomegaly, posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus, and periventricular hemorrhagic infarction.1 Periventricular leukomalacia is necrosis of cerebral white matter with a characteristic distribution dorsolateral to the external angles of the lateral ventricles and adjacent to the trigones and to the frontal horn and body of the lateral ventricles.30 In the preterm infant, this region is more vulnerable to insults such as ischemia or infection30; parts of the immature brain are more vulnerable to various insults and become less vulnerable as the brain matures. Several reasons have been proposed to explain this. These include the vascular anatomy in the preterm infant, in whom two systems supply blood to the cerebral hemispheres; both course from the brain surface. The ventriculofugal system travels down to the ventricles and then back into the brain toward the cortex. The ventriculopetal system penetrates into the brain toward the ventricles. The systems form a boundary zone around the ventricles, which can become a watershed region.31 Glial cells in the periventricular region, particularly oligodendrocytes, are vulnerable to damage, inasmuch as they are actively differentiating and their metabolic activity is increased. They are also more prone to excitotoxic damage brought about by glutamate, which increases after ischemic injury and is mediated by free radical attack.1 The region is also susceptible to cytokines, which are produced in maternal and fetal infections.32

ACQUIRED POSTNATAL CAUSES

Most acquired postnatal cases of cerebral palsy are the spastic form.33 Causes include severe hypoxic-ischemic insults such as near-drowning, stroke, trauma, and infection.

PROGNOSIS

Most children with cerebral palsy survive to adulthood, survival depending on the degree of disability.34 Although the rate of mortality is affected by the aggressiveness and quality of care, patients who are immobile and require tube feeding are more likely to die early from respiratory disease.35

Early prediction of motor outcome can be difficult and depends on several factors.1,36,37 The prognosis for walking is poor in children who do not achieve head control by age 20months, retain primitive reflexes and have no postural responses by age 24 months, and do not crawl by about 5 years of age. Conversely, the prognosis for walking is good for those who sit independently by age 2 years and crawl before 30 months. Restricted or aided ambulation may be achieved by those who sit between ages 3 and 4 years. Intelligence, social factors, and the availability of services may affect these outcomes.

MANAGEMENT

The priorities of management are listed in Table 121-2. Details of these are beyond the scope of this chapter. However, of importance is that management is best delivered in specialized multidisciplinary clinics or centers that have access to psychologists, social workers, and therapists.

TABLE 121-2 Priorities of Management of Cerebral Palsy in Order of Importance

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Pediatrics. Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy: Defining the Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2003.

Ashwal S, Russman BS, Blasco PA, et al. Diagnostic assessment of the child with cerebral palsy. Neurology. 2004;62:851-863.

Ferriero DM. Neonatal brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1985-1995.

Miller G, Clark GD, editors. The Cerebral Palsies. Causes, Consequences, and Management. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1998:1-36.

O’Shea TM. Cerebral palsy in very preterm infants: new epidemiological insights. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002;8:135-146.

1 Miller G. Cerebral palsies: an overview. In: Miller G, Clark GD, editors. The Cerebral Palsies. Causes, Consequences, and Management. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1998:1-36.

2 Ferriero DM. Neonatal brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1985-1995.

3 Cooper J, Majnemer A, Rosenblatt B, et al. The determination of sensory deficits in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. J Child Neurol. 1995;10:300-3007.

4 Menkes JH, Curran J. Clinical and MR correlates in children with extrapyramidal cerebral palsy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:451-457.

5 Miller G, Cala LA. Ataxic cerebral palsy—clinicoradiologic correlation. Neuropediatrics. 1989;20:84-89.

6 Murphy CC, Yeargin-Allsopp M, Decoufle P, et al. Prevalence of cerebral palsy among 10-year-old children in metropolitan Atlanta 1985 through 1987. J Pediatr. 1993;123:513-520.

7 Rogers B. Feeding method and health outcomes of children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr. 2004;145(2 Suppl):528-532.

8 Scott BL, Jankovic J. Delayed-onset progressive movement disorders after static brain lesions. Neurology. 1996;46:68-74.

9 Zafeirou DI, Tslkoulas IG, Kremenopoulos GM. Prospective follow-up of primitive reflex profiles in high-risk infants: clues to an early diagnosis of cerebral palsy. Pediatr Neurol. 1995;13:148-152.

10 Rutherford MA, Pennock JM, Counsell SJ, et al. Abnormal magnetic resonance signal in the internal capsule predicts poor neurodevelopmental outcome in infants with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 1998;102:323-328.

11 Hunt RW, Neill JJ, Coleman LT, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient in the posterior limb of the internal capsule predicts outcome following perinatal asphyxia. Pediatrics. 2004;114:999-1003.

12 Neil JJ, Inder TE. Imaging perinatal brain injury in premature infants. Semin Perinatol. 2003;28:433-443.

13 Yin R, Reddihough D, Ditchfield M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Child Health. 2000;36:139-144.

14 Ashwal S, Russian BS, Blasco PA, et al. Diagnostic assessment of the child with cerebral palsy. Neurology. 2004;62:851-863.

15 Nelson KB. The epidemiology of cerebral palsy in term infants. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002;8:146-150.

16 Perlman JM. Intrapartum hypoxic-ischemic cerebral injury and subsequent cerebral palsy: medico-legal issues. Pediatrics. 1997;99:851-859.

17 Lorenz JM, Wooliever DE, Jetton JR, et al. A quantitative review of mortality and developmental disability in extremely premature newborns. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:425-435.

18 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Pediatrics. Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy: Defining the Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2003.

19 Ross ME, Walsh CA. Human brain malformations and their lessons for neuronal migration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1041-1070.

20 Chang BS, Piao X, Gianni C, et al. Bilateral generalized polymicrogyria (BGP): a distinct syndrome of cortical malformation. Neurology. 2004;62:1722-1728.

21 Foldrary-Schaefer N, Bautista J, Andermann F, et al. Focal malformations of cortical development. Neurology. 2004;62(Suppl 3):S14-S19.

22 Suri M. The phenotypic spectrum of ARX mutations. Dev Med Clin Neurol. 2005;47:133-137.

23 Petterson B, Nelson KB, Watson L, et al. Twins, triplets, and cerebral palsy in births in Western Australia in the 1980′s. BMJ. 1993;307:1239-1243.

24 Pharoah PO. Twins and cerebral palsy. Acta Pediatr. 2001;90(Suppl 436):6-10.

25 Hanigan WC, Powell FC, Miller TC, et al. Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage in full term infants. Child Nerv Syst. 1995;11:698-703.

26 Roland EH, Flodmark O, Hill A. Thalamic hemorrhage with intraventricular hemorrhage in the full term newborn. Pediatrics. 1990;85:737-742.

27 Wu YW, Escobar GJ, Grether JK, et al. Chorioamnionitis and cerebral palsy in term and near-term infants. JAMA. 2003;290:2677-2684.

28 O’Shea TM. Cerebral palsy in very preterm infants: new epidemiological insights. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002;8:135-146.

29 Nelson KB, Dambrosia JM, Grether JK, et al. Neonatal cytokines and coagulation factors in children with cerebral palsy. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:665-675.

30 Inder TE, Volpe JJ. Mechanisms of perinatal brain injury. Semin Neonatal. 2000;5:3-16.

31 Takashima S, Tanaka K. Development of cerebrovascular architecture and its relationship to periventricular leukomalacia. Arch Neurol. 1978;35:11-19.

32 Dammann O, Leviton A. Maternal intrauterine infection, cytokines, and brain damage in the preterm newborn. Pediatr Res. 1997;42:1-8.

33 Pharaoh PO, Cooke T, Rosenbloom L. Acquired cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64:1013-1016.

34 Strauss D, Shavelle R. Life expectancy of adults with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40:369-374.

35 Eyman RK, Grossman HJ, Chaney RH, et al. Survival of profoundly disabled people with several mental retardation. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:329-336.

36 Molnar GE, Gordon SU. Cerebral palsy: predictive value of selected clinical signs for early prognostication of motor function. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1979;57:153-158.

37 Rosenbaum PL, Walter SD, Hanna SE, et al. Prognosis for gross motor function in cerebral palsy: creation of motor development curves. JAMA. 2002;288:1357-1363.