Common neurological conditions seen in the long case are stroke, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy and myasthenia gravis. Any one of these conditions can be the main problem of the case. But many other neurological conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease, other movement disorders, peripheral neuropathy, migraine, vertigo, tinnitus and myelopathy, can be present as an associated problem. It is important to look at the case as a whole when encountering these features, because another medical condition or a medication may be the causative factor of the neurological deficit. In such situations, treating the possible precipitating condition or changing the medication may resolve the neurological problem. An example is a patient with a background history of hepatitis C presenting with peripheral neuropathy. The neuropathy is sometimes caused by hepatitis C-associated cryoglobulinaemia. So it is important to contextualise the neurological symptoms and signs, in the interplay of multiple diseases and medications in the long case.

Neurology

It is unusual to encounter a significantly demented patient in the long case examination. However, there have been instances where patients with progressive dementia, but who could still hold a reasonably rational conversation, have been presented at the examination. The objective of such long cases is to assess the candidate’s ability to identify the problem of progressive intellectual deterioration and the candidate’s knowledge and skills in handling the issues involved, such as remedying any correctable causes, attempting to slow down the deterioration where possible, and preparing for the optimal care of the patient medically and socially in anticipation of the inevitable total dementia.

The candidate should try to identify the broad pattern of cognitive impairment and the type of dementia. The following is a very basic introduction to such classification:

Candidates should be able to perform a very quick assessment of the patient’s cognitive function, and a formal ‘mini mental’ test is a useful tool for this. Because this is a standardised and quantitative test, it can provide an objective assessment (though not always very accurate) that would be acceptable to the examiners. A good method to employ here is to memorise the mnemonic, which incorporates the important components of the mini mental test:

O R A — R L C

O Orientation—year/season/month/date/day, country/state/city/hospital/floor (10 points)

R Registration—three words: window, basketball, tree (4 points)

A Attention—serial sevens, or counting backwards from 100 by sevens, or spelling WORLD backwards (5 points)

R Recall—the three words above (3 points)

L Language skills—repeating a phrase such as West Register Street, naming two objects, reading a sentence, writing a sentence and obeying a three-stage command (8 points)

C Construction—copying two intersecting pentagons (1 point).

The maximum score is 30. A score of < 25 may suggest dementia.

In addition to the above assessment, look for features that may give clues to possible intellectual impairment. General demeanor, the response to your initial introduction, smell of urine and extrapyramidal facies are some such important clues. Check for the frontal reflexes.

In patients with suspected dementia, a standard dementia screen is warranted. This battery of tests includes:

1. CT or MRI of the head

2. Full blood count with vitamin B12 and folate levels

3. Thyroid function tests

4. Midstream urine for microscopy and culture

5. Venereal disease research laboratory test for syphilis

6. Vasculitic and connective tissue disease screen

7. Electroencephalogram (EEG)

8. HIV serology in the young demented.

When approaching a stroke patient, the candidate should be well versed in the basic principles of stroke management.

The history must be very detailed and accurately describe the neurological symptoms. Ask about:

• how the patient manages with the neurological deficit

• any history of atrial fibrillation, palpitations, migraine, manipulation of the neck (a precipitating cause for dissection of the carotid or vertebral artery)

• any recent cardiac investigations such as coronary angiography

• recent cessation of anticoagulant therapy for some reason in patients with atrial fibrillation.

In the young stroke patient, consider the possibility of patent foramen ovale and paradoxical embolus.

Also obtain history regarding other thrombotic events (DVT, PE, miscarriages) in the patient or first-degree family members. Ask about alcohol consumption and recent falls that may have caused an intracranial haemorrhage.

Enquire about premorbid as well as the current level of independence and mobility. If the patient is incapacitated, ask about the social support available at home. Ask about the patient’s mood.

Never forget to look for poorly controlled hypertension, fundoscopic changes of hypertension and diabetes, carotid bruits, orbital bruits (commonly heard in the side opposite the carotid occlusion, due to increased contralateral flow), atrial fibrillation, cardiac murmurs and evidence of peripheral vascular disease.

Check the blood pressure in both arms (a difference of more than 20 mmHg systolic may suggest subclavian stenosis and a steal phenomenon). Look for complications such as pressure sores, limb contractures and disuse atrophy of the weak limbs.

See whether the patient has a percutaneous gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tube inserted and, if present, inspect for cellulitis or pus around the insertion site. Check the patient’s temperature and look at the temperature chart for any evidence of fevers. Check for DVT in the lower limbs if a peripheral embolic cause is suspected, especially in the younger patient.

With the history and the physical examination, the candidate should be able to accurately characterise the exact neurological deficit and localise the area of the brain involved.

Depending on the type and severity, transient ischaemic attack may be managed at home if timely investigation and adequate treatment can be arranged. Stroke with residual neurological deficit needs to be managed in hospital. Essential therapeutic goals in a stroke patient are early rehabilitation, the prevention of secondary complications such as DVT, aspiration pneumonia, urinary tract infections, limb contractures and pressure sores, prevention of recurrent stroke, and identifying/treating stroke risk factors. Rehabilitation should be planned according to the deficits identified on the examination.

Younger stroke patients (aged under 40 years) should be screened for unusual causes, such as illicit drug use (cocaine), vasculitic disorders, subacute bacterial endocarditis, patent foramen ovale or cardiac septal defects with a right-to-left shunt, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter, thrombophilia, and inherited disorders such as CADASIL (see box) and homocystinuria. Some patients can develop a ‘post-stroke dementia’, and therefore the patient’s cognitive function should be assessed.

• Atherosclerosis of the carotid or vertebrobasilar arterial systems

• Hypertension (lacunar infarcts due to arteriosclerosis of small penetrating arteries of the brain)

• Atrial fibrillation leading to thromboembolism

• Left ventricular aneurysm with mural thrombus

• Spontaneous/traumatic intracranial haemorrhage

• Amyloid angiopathy

• Cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leucoencephalopathy (CADASIL)

• Vasculitis

• Connective tissue disorders (e.g. systemic lupus erythmatosus (SLE))

• Narcotic use (e.g. cocaine, amphetamines)

• Bacterial endocarditis (septic emboli/mycotic aneurysm rupture)

• Thrombophilia (e.g. factor C/S deficiency, factor V gene mutation)

• Hypercoagulable states (e.g. polycythaemia, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura)

• Cerebral venous thrombosis

• Dissection of extracranial arteries

• Intracranial neoplasms (primary/secondary)

• Cerebral vascular malformations

• Subclavian steal syndrome

The following investigations should be considered for the stroke patient, as guided by the clinical assessment:

1. Urine analysis and blood sugar levels—to exclude diabetes mellitus or a precipitating urinary tract infection

2. Full blood count—looking at haemoglobin levels (to exclude polycythaemia), white cell count (to exclude sepsis as a precipitating cause) and platelet count (rarely, essential thrombocythaemia can contribute to stroke)

3. Coagulation profile

4. ESR—to exclude any inflammatory arteritic/vasculitic process

5. Chest X-ray—for cardiomegaly/neoplasms/aspiration

7. Fasting blood lipid profile

8. CT or MRI of the head—looking for ischaemic infarcts, haemorrhage or mass lesions

9. Doppler scan of the carotid arteries—and, if the duplex ultrasonography suggests significant carotid stenosis, consider obtaining another confirmatory imaging study such as carotid CT angiography, carotid digital subtraction angiography or MR angiography. If the diagnosis is confirmed, discuss possibility of interventions such as carotid endarterectomy or stent placement in suitable patients.

10. If the patient is in AF, ask for the results of the transoesophageal echocardiogram (TOE)—looking for thrombus or spontaneous echo contrast in the left atrial appendage. This may also show up any atheromatous plaques in the ascending aorta and the arch of aorta that may have contributed to the stroke.

11. In the younger stroke patient, consider also the following investigations:

• drug screen—looking for narcotic agents

• vasculitic screen—if there are features of vasculitis

• blood cultures and cardiac imaging—if endocarditis is suspected

• cardiac event monitor—looking for paroxysmal AF

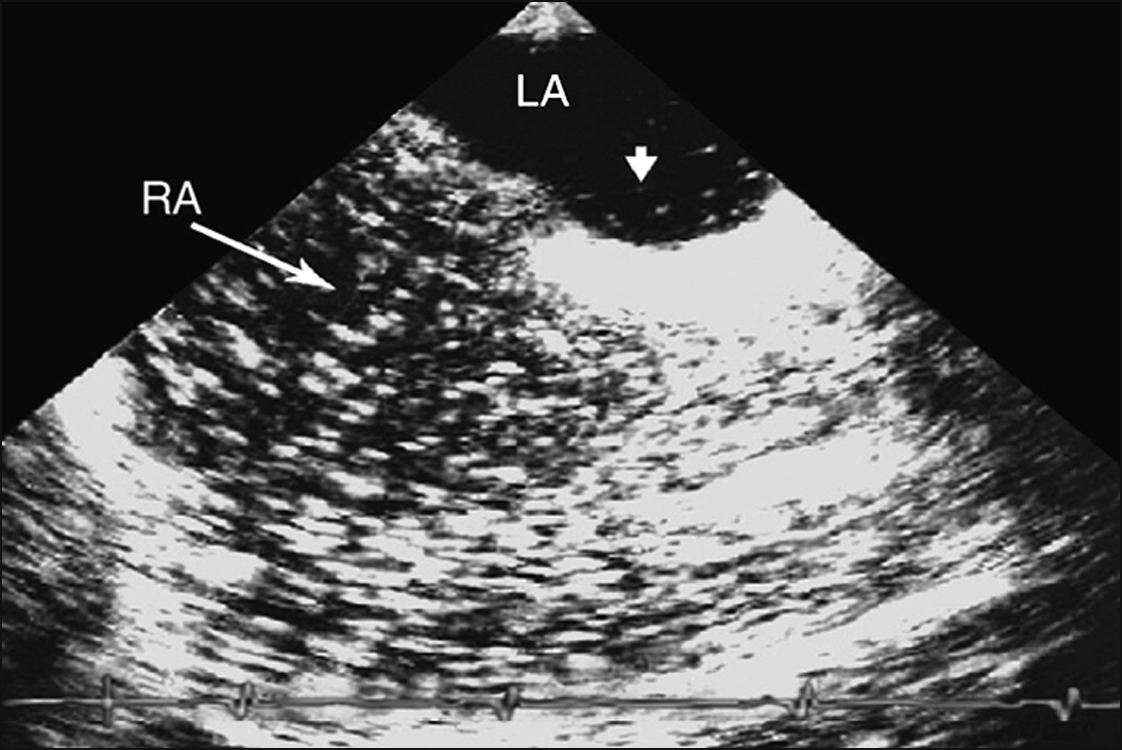

• thrombophilic screen, and transthoracic echocardiogram with bubble study—looking for patent foramen ovale (PFO) (Fig 5.1) or septal defect.

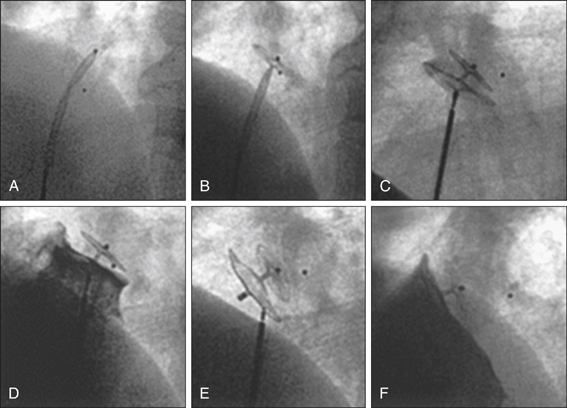

If there is evidence of right-to-left shunt, particularly when right-sided pressures become high (as in Valsalva manoeuvre), a follow-up TOE is indicated to better characterise this shunt with a view to closing it (Fig 5.2).

The goals of stroke management are: 1) to determine and address the causative factors (secondary prevention), and 2) to restore functionality.

1. Control blood pressure—Initial steps are adequate and cautious control of the blood pressure (aggressive lowering of blood pressure in ischaemic stroke can worsen the neurological damage) and serum glucose level, and-antiplatelet therapy in the form of aspirin, clopidogrel or aspirin/sustained-release dipyridamole combination. Dipyridamole can cause side effects of headache, which may complicate the initial stroke symptoms. The popular approach is to use aspirin during the first few days post ischaemic stroke. This can later be changed to aspirin/sustained-release dipyridamole combination. Clopidogrel may be used in aspirin-intolerant patients. There is also an important role for ‘statin’ cholesterol-lowering agents and ACE inhibitors in the setting of acute stroke.

2. Anticoagulation—If the patient is in AF, there is high suspicion of cardioembolic event or there is carotid/vertebral dissection, anticoagulation with heparin or enoxaparin should be considered. This carries with it a risk of secondary haemorrhagic transformation of the ischaemic infarct, particularly within the first 2 weeks of the event and in cases involving a large vascular territory. For patients with AF, especially in the setting of a large stroke, it is wise to observe for a few days and repeat the cranial CT prior to commencing anticoagulation therapy.

3. Treat the cause and give supportive therapy—Other steps in the general management of the stroke patient include treatment of the specific cause, if one is found (e.g. polycythaemia, vasculitis), and supportive therapy using adequate hydration, prophylactic anticoagulation, pressure care, and antispasmodics such as baclofen (use this agent with caution, as it can lower the seizure threshold in susceptible individuals) to relieve painful muscle spasms. Botulinum toxin is useful in relieving the painful spastic contractures that develop later. The immobilised patient is predisposed to DVT; therefore, prophylactic measures should be initiated. Compression stockings, low-dose subcutaneous unfractionated or fractionated heparin and passive limb movement are some such measures. Vigilance for pressure sores and implementation of preventive measures are also essential. Prophylactic measures are: change of posture at least at 2-hourly intervals, use of a waterbed, pressure-controllable mattress, and good nursing care.

4. Definitive therapy—Definitive therapy in the form of carotid endarterectomy or carotid stenting should be considered if there is more than 70% atherosclerotic stenosis of the carotid artery and the stroke is consistent with the arterial lesion in that distribution.

5. Team approach—A team approach to management of the patient is essential. Early physiotherapy to prevent limb contracture and facilitate mobilisation, speech pathology review for optimisation of feeding (this may include video-telemetric swallowing assessment) and for rehabilitation of speech, occupational therapy to review the level of independence and the need for any support, and the social worker’s involvement to assess the financial issues and social support for the patient and the family, are all important aspects of the management. It is wise to get the discharge planner involved early and to consider a family conference if indicated.

6. Treat depression—Stroke victims often become clinically depressed, and this will have a negative effect on the rehabilitation process, where the patient’s active participation is highly desired. Consideration should therefore be given to commencing an antidepressant with minimal anticholinergic effects if indicated. An agent such as citalopram is suitable.

7. Monitor temperature—Patients should be monitored closely for temperature spikes. Pneumonia (aspiration) is common among stroke victims and has been identified as a major cause of mortality.

8. Feeding—Oral feeding should be suspended until the possibility of aspiration is formally excluded. If the patient is unable to tolerate oral feeding for more than 5 days, a decision should be made regarding the insertion of a percutaneous gastrostomy feeding tube, as impaired bulbar muscle function may be permanent.

9. Rehabilitation—Remember, rehabilitation is the key issue in the stroke patient!

Classification of the patient’s seizure type has diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic significance. It is important to study the different seizure classification systems used in common clinical practice, such as the one defined by the International League against Epilepsy (see box). It is not uncommon for patients to be suffering from a combination of seizure types. Presentation of a simple partial seizure can take many forms. However, there is uniformity in the features of a single patient.

Partial seizure

Simple partial (consciousness not impaired)

With motor symptoms:

With somatosensory or special sensory symptoms:

With autonomic symptoms or signs (including epigastric, pallor, sweating, etc)

With psychic symptoms (disturbance of higher cerebral function)—usually occur with impairment of consciousness and classified as complex partial:

Complex partial (with impairment of consciousness)

Generalised seizure

Non-convulsive (absence)

Convulsive

Unclassified seizure

(Adapted from Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League against Epilepsy 1981 Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 22:489)

(Adapted from Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League against Epilepsy 1981 Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 22:489)

Ask about:

• prodromal signs—such as déjà vu and jamais vu

• auras—such as pungent smells, anxiety and abdominal discomfort

• events occurring during the first few seconds of each seizure—this is of utmost importance. Often, seizures start focally and then generalise within a few seconds. This will enable the clinician to determine the type of seizure (focal onset versus general onset).

• jerky limb movements or staring

• impairment or loss of consciousness

• automatisms—such as lip smacking, chewing

• how eyewitnesses describe the episodes—observers may report automatisms and loss or impairment of consciousness

• whether the patient is aware or unaware of the events that take place during a complex partial seizure. Progression of simple partial seizures to complex partial seizures is common. In complex partial seizures, the person demonstrates impairment of consciousness together with automatisms. Generalised seizures always cause impairment of consciousness together with tonic–clonic activity (grand mal seizures), myoclonic jerks or absence (petit mal seizures). The patient may know of observer reports to this effect.

• postdromal features—such as Todd’s paralysis and excessive drowsiness. Such postictal paresis can last from hours to days. The features of Todd’s palsy can also include hemianopic visual loss or sensory impairment and always involve the contralateral side to the side of seizure focus. In complex partial seizures, postdromal features include severe headaches and confusion.

• family history of epilepsy—some epilepsy syndromes, such as juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) are hereditary

• possible precipitants of seizures—such as flickering lights, sleep deprivation. Controlling modifiable seizure triggers helps give better seizure control.

• relevant past history—such as head injuries, febrile seizure as a child, brain surgery, intracranial tumour, stroke, encephalitis or meningitis

• consumption of extraneous agents and conditions that can lower seizure threshold—such as alcohol, recreational drugs and hypoglycaemia

• whether the patient has ever been monitored in hospital with video-telemetry

• any previous episodes of self-harm due to fits.

Occupational issues are very important in the epileptic, so discuss operation of heavy machinery and driving. Discuss in detail any social issues and limitations that are important to the patient. Details about depression and/or the use of antidepressants are important, as all antidepressants (especially tricyclic agents) have a propensity to lower the seizure threshold. Never forget to ask about the reproductive plans of the female patient, as antiepileptic agents can be teratogenic. The oral contraceptive pill can be rendered ineffective by agents such as phenytoin.

Usually during non-ictal periods the examination is unremarkable in most epileptic patients. However, a thorough general neurological examination is indicated, particularly looking for evidence of focal neurologial signs. Cranial scars may testify to previous brain surgery or brain injury.

1. If it is the first episode of fitting—serum calcium (hypocalcaemia), sodium (hyponatraemia) and magnesium (hypomagnesaemia) levels as well as serum glucose measurement, looking for hypoglycaemia. Screening for infection, hypoxia, drug effects and other metabolic derangements is also necessary.

2. Electroencephalograph (EEG)—to identify an underlying seizure focus if present. Recurrent fitting with normal EEG during the interictal period may warrant in-hospital video-telemetry to capture an event.

3. Cranial CT or MRI—looking for structural abnormality such as space-occupying mass, stroke or demyelination plaque.

4. Recurrence of fitting while on antiepileptic therapy warrants assessment of serum levels of the relevant agent.

1. All symptomatic seizures with an underlying cause should be treated.

2. Treatment of idiopathic seizures (with normal EEG and MRI) should be initiated if the patient experiences more than two seizures. The most common cause of inadequate epilepsy control is poor drug compliance. Also be alert to the concurrent use of drugs that induce hepatic microsomal enzymes, which metabolise antiepileptic agents. Factors that would contribute to recurrent seizures include brain structural abnormalities, presence of focal neurological deficits and mental retardation.

Many factors need to be considered before deciding on the optimal drug or combination. These include seizure type, drug tolerability, drug interactions (and therefore comorbidities), and the patient’s age and lifestyle. It is important to attempt monotherapy initially. Combination should be considered only after two sequential monotherapy attempts with two different agents have failed. Sodium valproate is considered a ‘broad-spectrum’ antiepileptic and can be used to treat most types of seizures. Generalised absence seizures (petit mal), which usually occur in children, are treated with ethosuximide. Generalised tonic–clonic seizures can be treated with carbamazepine and phenytoin.

Carbamazepine and sodium valproate should be avoided in severe liver failure. Phenytoin dose should also be reduced in such circumstances. Patients on carbamazepine should be monitored for development of rash, fever, bruising and leucopenia. Carbamazepine and phenytoin can cause interstitial nephritis. Because of its unique pharmacokinetics, a slight dose increase in phenytoin may result in major serum level elevation, especially in the elderly. Valproate can cause an increase in the hepatic transaminase levels as well as thrombocytopenia and platelet dysfunction leading to bleeding. Carbamazepine should not be used in generalised absence seizures. Carbamazepine and phenytoin cause induction of the hepatic cytochrome P-450 enzyme system, while valproate causes an inhibition of the same, and therefore it is important to make relevant dose adjustments to the concurrently administered other drugs that are metabolised by the liver. This is particularly important in female patients of childbearing age, because the efficacy of oral contraceptive agents will be compromised when administered concurrently with an agent that induces hepatic microsomal enzymes.

When these first-line agents are ineffective or are not tolerated, a second-line agent such as lamotrigine, topiramate, levetiracetam or gabapentin may be tried. Lamotrigine has a therapeutic profile similar to that of sodium valproate. It can be used as monotherapy or as add-on therapy in partial and generalised seizures. When given in combination, sodium valproate causes significant elevation of the lamotrigine level and the lamotrigine dose needs to be halved. The most significant side effect associated with this agent is severe rash, which can progress to Stevens-Johnson syndrome and is potentially life-threatening. Very slow titration is the key in lowering the rate of skin reaction. Topiramate is a novel agent that can be used in generalised as well as partial seizures. Some side effects of topiramate are somnolence, memory impairment, fatigue, anorexia and nausea. Levetiracetam is also a new agent effective in partial onset seizure control. Gabapentin is considered a safe drug, with no drug interactions and a minimal adverse-effect profile. The second-line agents overall have a lower side- effect profile and fewer concerns with drug interactions. These agents also do not require monitoring of serum levels.

All patients need counselling and help with occupational issues, the psychological impact of this chronic condition, and driving. Family and partner involvement in the management of patient, trigger factor control and drug compliance are important points to address in the discussion.

• Partial or generalised tonic–clonic seizures—sodium valproate, carbamazepine, phenytoin

• Absence seizures—ethosuximide, sodium valproate

• Myoclonic seizures—sodium valproate, lamotrigine, topiramate

• Second-line therapy for partial and generalised tonic–clonic seizures—topiramate, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam

• Lennox-Gastaut syndrome—felbamate (can cause fatal aplastic anaemia and severe liver toxicity)

The diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS) by definition requires evidence of central nervous system lesions separated in time and place.

Enquire about the onset, initial neurological deficit, any episodes of reversible visual loss or ocular pain, weakness, incoordination, lancinating pain, speech impairment, sphincter disturbances, sensory loss, seizures, vertigo and gait difficulty. Check for Lhermitte’s phenomenon (electric shock-like pain radiating down the spine, triggered by neck flexion).

Try to determine the disease’s pattern and the temporal profile. Most patients initially suffer from relapsing–remitting disease, with relapses of neurological symptoms followed by full or partial recovery. Many progress to develop secondary progressive disease with increasing disability. A minority of patients (10%) suffer from primary progressive multiple sclerosis, where there is progressive deterioration from the onset without any remissions.

Ask about complications associated with neurological deficit, such as aspiration pneumonia, urinary tract infection, mechanical injuries, limb contractures, pressure areas and painful muscle spasms.

It is important to assess the functional level of the patient, social and occupational difficulties, financial situation and the support available. Ask about activities of daily living and difficulties associated with sexual function.

Assess the mood of the patient, as this may vary from euphoria to severe depression at different times. Ask about the presence of severe fatigue, and also whether the patient has noticed exacerbation of symptoms with rises in body temperature.

Family history and the patient’s place of birth may also reveal important information. Ask about pregnancy in the female patient, as there is a 20–30% increase in the relapse rate in the first month after delivery of the baby.

The patient should be questioned regarding different treatments given over the years and any adverse effects associated with them.

The history should be followed by a very detailed neurological examination. Look for disturbances of external ocular movements and other eye signs, such as internuclear ophthalmoplegia, optic atrophy and afferent pupillary defect. Examine for spinal cord signs such as spastic paraparesis (try to define the level), bulbar signs, cerebellar signs (especially cerebellar speech) and cerebral hemispheric signs. Perform a Mini-Mental State Examination to assess cognitive function, as multiple sclerosis can lead to cognitive impairment.

1. MRI of the brain and spinal cord with gadolinium enhancement—looking for periventricular and callosal plaques in the brain and plaques in the brainstem and spinal cord.

2. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination—looking for oligoclonal immunoglobulin G bands (a serum sample checked at the same time should test negative for oligoclonal bands) and mononuclear pleocytosis and also to exclude other infectious/inflammatory conditions.

3. CSF examination may be indicated in cases where there are no abnormalities detected in the MRI despite highly suggestive clinical features.

4. Visual, somatosensory and auditory evoked potentials, to demonstrate subclinical disease.

5. Exclusion of other metabolic/inflammatory conditions such as vitamin B12 deficiency (subacute combined degeneration), connective tissue disorders, sarcoidosis, Sjögren’s disease, HIV etc.

Mild attacks of multiple sclerosis do not usually require treatment. Spontaneous improvement is the norm.

More severe attacks with disabling or painful symptoms should be treated with high-dose parenteral pulsed methylprednisolone for 3–5 days. This therapy is known to accelerate remission but has no effect on the progression of the disease.

Therapy with interferon beta-1a or 1b has been shown to retard the progression of relapsing–remitting disease. Interferon 1b has its use in secondary progressive disease too. Objectives of this therapy are to reduce the frequency and the severity of relapses. Some patients may develop neutralising antibodies to these agents, potentially rendering them ineffective. Interferon 1b is injected subcutaneously. Different formulations of interferon 1a can be injected subcutaneously or intramuscularly.

Patients may experience distressing flu-like symptoms with these therapies, and should be forewarned and at times premedicated with antipyretic agents.

A synthetic agent, glatiramer acetate, has been shown to be similarly helpful in the management of relapsing–remitting disease. This agent is useful for patients who do not tolerate interferon-beta. It has a slow onset of action (2–3 months) compared to the interferon preparations. A newly approved medication, natalizumab which is a monoclonal antibody to alpha4-integrin, has been shown to be highly effective in relapsing–remitting MS but careful monitoring is required due to an association with an increased risk of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML).

Painful muscle spasms can be managed with oral baclofen or diazepam. Botulinum toxin injections have also been used in severe cases. Distressing neurogenic pain can be managed with antiepileptic agents such as carbamazepine, phenytoin and gabapentin, or tricyclic antidepressants such as amytriptyline and nortriptyline. Urge incontinence is common and can be treated with anticholinergic agents, such as propantheline or oxybutynin. Those who suffer from urinary retention should be taught how to perform intermittent self-catheterisation. They may benefit from prophylactic antibiotics against the development of recurrent urinary tract infections.

Management of complications and symptomatic treatment should be approached in a multidisciplinary manner. Collaboration between the physiotherapist, the occupational therapist, the social worker and the psychologist is very important in formulating a comprehensive plan of management for the patient. Patient education and counselling should be given prominence. Patients who need assistance should be encouraged to join support groups such as the Multiple Sclerosis Society and other relevant local organisations.

This disorder is characterised by a T-cell-dependent antibody-mediated autoimmune response to acetylcholine receptors in the neuromuscular junction.

Ask about:

• the onset

• the age at which the diagnosis was made

• duration

• details of exacerbations—frequency and trigger factors

• how the degree of weakness fluctuates in the different skeletal muscle groups. Involvement of ocular, bulbar, thoracic respiratory and limb musculature is a hallmark of this disorder.

• whether the patient has been treated with penicillamine in the past. Penicillamine therapy is a classic cause of drug-induced myasthenia gravis, and it almost always resolves once the medication is ceased.

• any history of thyroid disease (Graves’ disease coexists in 2–5% of patients) or Addison’s disease

• previous hospitalisations and any episodes where intubation and ventilation were necessary.

Patients suffer from diplopia, ptosis, dysphagia, dysarthria, weakness, lethargy and fatiguability of the muscles with repeated use. Complications of the condition include aspiration, respiratory failure and thromboembolism.

Ask about:

• therapy and therapy-related complications

• how the patient is coping with the condition

• support available in the community

• other known organ-specific autoimmune disorders that the patient may be suffering from

• drug-induced exacerbations of symptoms and the culprit agents—gentamicin is one such agent.

1. Look for cushingoid body habitus secondary to repeated therapy with corticosteroids, and for ptosis and drooling.

3. Perform a thorough neurological examination, looking for weakness in the extraocular muscles, facial muscles, the bulbar area and the limbs. Note that the reflexes and the sensory function are preserved. In very chronic, ‘burnt-out’ myasthenia, wasting of the muscles can be a prominent feature.

4. Assess the patient’s forced vital capacity.

1. Radioimmunoassay—for anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody.

2. Tensilon (edrophonium chloride) test—an objective improvement of muscle strength after parenteral Tensilon® is diagnostic of myasthenia gravis. Remember that Tensilon®can cause severe, potentially lethal bradycardia, complete heart block and severe bronchospasm, so the patient must be monitored during this test. It is essential that atropine and a resuscitation trolley be available by the bedside during the study.

3. Ice pack test—can be performed in patients suffering from ptosis. Neuromuscular transmission is known to improve at lower temperatures. The test involves assessing for objective improvement of muscle power in the eyelids upon cooling. This test is a useful substitute for the Tensilon® test when the latter is contraindicated.

4. Neurophysiological tests—such as repetitive nerve stimulation test, looking for muscle fatiguability, and single-fibre electromyography, looking for features of block and jitter.

5. CT or MRI of the brain—to exclude other pathology.

6. Formal lung function studies, looking for a restrictive-type abnormality, and chest X-ray to exclude aspiration and atelectasis.

7. Thyroid function tests—to exclude thyroid ophthalmopathy.

8. ECG—looking for evidence of pulmonary hypertension associated with chronic hypoventilation and recurrent aspiration.

9. CT or MRI of the anterior mediastinum—looking for a thymic mass. If thymectomy has been performed, ask for the biopsy report during the discussion, to exclude thymoma.

Management of myasthenia gravis should be individualised to each patient, based on the muscle groups involved and the level of their involvement.

1. Symptom management—achieved with anticholinesterase agents such as neostigmine and pyridostigmine. Note that overmedicating with anticholinesterase can also cause weakness together with other cholinergic side effects such as diarrhoea and abdominal cramps.

2. Immunosuppression—this is the mainstay of management and disease control. Immunosuppression with chronic systemic corticosteroid therapy is used for maintenance. Steroid-sparing therapy can also be achieved with the use of azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil or cyclophosphamide. Remember to raise the issue of complications associated with immunosuppression, such as opportunistic infections and secondary malignancies due to long-term cytotoxic use. Sometimes immunosuppressed myasthenia patients are treated with prophylactic sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim against Pneumocystis carinii.

3. Thymectomy—should be performed in all patients with thymoma due to its propensity to spread locally. All patients with generalised myasthenia gravis under the age of 55 years may benefit from thymectomy even in the absence of thymic tumour. However, the value of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis is currently under investigation.

4. Plasmapheresis or IV immunoglobulins—for temporary and rapid control of symptoms in severe disease (such as myasthenia crisis) and prior to surgery.

5. Monitoring with regular spirometry—to diagnose respiratory exhaustion promptly.

Myasthenia crisis is a life-threatening exacerbation of the disease, with progressive inability to breathe due to severe muscle weakness. This must be differentiated from the cholinergic crisis due to excessive anticholinesterase therapy. This situation should be addressed in an intensive care setting, where facilities are available for intubation and ventilation.

The patient should be given adequate chest physiotherapy and meticulous nursing care to prevent complications and pressure sores. The patient may need prophylactic antibiotics to prevent sepsis, and parenteral or nasogastric feeding to ensure adequate nutrition. Caution should be exercised with the use of neuromuscular blocking agents in patients undergoing surgery under general anaesthesia, as these agents can cause prolonged paralysis.

This disorder should be considered a differential diagnosis of a patient who presents with clinical signs of myasthenia gravis. Ask about the onset of early symptoms. Typically the patients initially experience proximal muscle weakness that manifests as difficulty in climbing stairs and getting out of a seat. This picture of weakness progresses to shoulder girdle weakness. Though ptosis may be seen, unlike myasthenia gravis the involvement of extraocular musculature and bulbar musculature is rare and the muscle weakness usually improves with exercise. In contrast to myasthenia, LEMS is commonly associated with autonomic dysfunction such as oromucosal dryness and impotence in men. LEMS could be a paraneoplastic phenomenon and therefore do not forget to ask about a diagnosis of a malignancy (such as small cell lung cancer). Investigations at the diagnosis of LEMS include repetitive nerve stimulation looking for an incremental response of the compound muscle action potential and antibodies to presynaptic voltage-dependent calcium channels.

Many a patient encountered as a long case will have a depressive component to their picture, simply due to their multiple and often chronic medical problems. It is important that the candidate be sensitive to the patient’s mood and pick up clues that suggest possible depression.

Look for a depressive affect, paucity of direct eye contact and sometimes paucity of movement. It is very important to enquire about intention to self-harm and suicide in all patients with suspected depression. If the patient has been treated with antidepressants, ask about any adverse effects experienced and about the efficacy of therapy.

If you think a patient is depressed, remember to formulate a plan of action to manage the condition. If you recommend pharmaceutical therapy for depression, remember to warn the patient that most antidepressants take about 2 weeks to start acting. The most commonly used antidepressant agents are the tricyclic antidepressants and the selective serotinin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

These agents can also be used in chronic pain, migraine prophylaxis and obsessive-compulsive disorder in addition to depression. The best agent for use in pain is amitriptyline and the best for obsessive-compulsive disorder is clomipramine. Adverse effects of tricyclics include sedation, dry mouth, constipation, weight gain, orthostatic hypotension, urinary retention, excessive sweating and agitation. Prior to commencing therapy, remember to check for postural blood pressure; also counsel the patient about the more common side effects, such as blurred vision and dry mouth, and reassure the patient that these effects will subside within about 7 days. For the elderly, two suitable agents with minimal anticholinergic effects are nortriptyline and desipramine. These agents are also less likely to cause sedation.

The side-effect profile of the SSRI agents includes nausea, agitation, insomnia, drowsiness, tremor, dry mouth, constipation and diarrhoea, and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH). These agents are becoming popular due to their minimal anticholinergic effects. Some of the more commonly used SSRIs include citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline and venlafaxine. The SSRI dose should be halved in renal failure.

All antidepressants are metabolised in the liver, so remember to halve the dose given to patients with liver failure.