Chapter 81 Neurological Problems of Pregnancy

Neurological Complications of Contraception

An international task force on combined oral contraceptives (COCs) (usually ethinylestradiol and levonorgestrel) and migraine cautiously suggested that women who suffer migraine and smoke tobacco should stop smoking before beginning COCs to reduce their risk of ischemic stroke. The task force identified COCs as potentially increasing the risk for ischemic stroke in women who have migraine with aura (Bousser et al., 2000). Consistent with this approach, other investigators reasonably suggest that the cautious use of COCs for a woman with migraine without aura who has a history of a stroke risk factor does not itself contraindicate the use of COCs.

Anticonvulsants do not affect the efficacy of medroxyprogesterone. Medroxyprogesterone may be the contraceptive pharmaceutical of choice in women with seizure disorders (Kaunitz, 2000). Based on theoretical considerations, some investigators recommend administering medroxyprogesterone injections every 10 weeks rather than every 12 weeks for women taking anticonvulsants that induce hepatic microsomal enzymes (Crawford, 2002).

Unwanted pregnancies with levonorgestrel use have occurred in women taking phenytoin and in women taking carbamazepine. Some researchers advise against the use of levonorgestrel in patients taking liver enzyme–inducing drugs of any kind, including enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants. Usual dose COCs, progesterone-only pills, medroxyprogesterone injections, and levonorgestrel implants have no known interactions and can be used in patients receiving valproic acid, vigabatrin, lamotrigine, gabapentin, tiagabine, levetiracetam, zonisamide, ethosuximide, and benzodiazepines. Failure of COCs with oxcarbazepine is reported in incomplete studies. A World Health Organization Working Group recommended against use of COCs, transdermal patch, vaginal ring, and progesterone-only pills for women taking phenytoin, caramazepine, barbiturates, primidone, topiramate, or oxcarbazepine due to reduced contraceptive effect (Gaffield et al., 2011).

In a careful study of small numbers of women, COCs lowered levels of lamotrigine by about 33%. This same study demonstrated that the lamotrigine levels of women in mid-luteal menstrual phase and not taking COCs dropped by about 31% (Herzog et al., 2009). Other studies report that when women take COCs, lamotrigine levels may decrease by half and some patients may suffer an increase in seizures. This effect is not seen when additional anticonvulsants are used with lamotrigine. Manufacturers of lamotrigine recommend that physicians increase that medication when patients taking lamotrigine monotherapy are placed on COCs.

Estrogen-containing oral contraceptive agents may worsen chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) and moyamoya disease, unmask systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), worsen migraine, and produce chorea in patients with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Based on recent studies, some physicians advise that an individually tailored contraceptive approach may include the recommendation of COCs in antiphospholipid antibody–negative patients with inactive or moderately active stable SLE (Bermas, 2005). The heightened risk for cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) in women taking oral contraceptive agents increases with prothrombin or factor V gene mutations.

Ethical Considerations

When a diagnosis of maternal death by neurological criteria is confirmed, a decision whether to continue medical interventions for the sake of a viable or marginally viable fetus is required. No consensus as to the conditions under which such medical intervention must be offered are established. Physicians sometimes turn to the ethically appropriate surrogate(s), sometimes one for the mother and one for the fetus, to discuss the foreseeable possible futures and ask the surrogate to make a decision with regard to offered medical therapies. A model written by the Council on Ethical Affairs of the California Medical Association, with variable applicability outside of the State of California, can be obtained online (CMA, 2009). In some states, the physician helps select surrogates. In others, a statute-driven “hierarchy” exists. Some states prohibit an appropriate surrogate from permitting the termination of pregnancy for an incapacitated patient but not when the patient is dead. Advising pregnant women to execute advance directives for medical care seems an unlikely and incomplete solution.

Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) scanning employs ionizing radiation with known risks of teratogenesis, mutagenesis, and carcinogenesis. In general, physicians avoid ionizing radiation during pregnancy, particularly between 8 and 15 weeks, the gestational period most sensitive to ionizing radiation. However, the risk is not as high as perceived by some medical professionals, and several authors urge an approach balanced to the diagnostic needs of the woman and fetus. Researchers estimate the average woman receives background radiation less than 0.1 rad over 9 months. Risks of fetal malformation demonstrably increase with radiation doses above 15 rads. Induced miscarriages and major congenital malformations occur at negligibly increased risk with doses to the fetus under 5 rads. Estimated radiation dosage from a typical CT scan of the brain is less than 0.050 rads when employing precautionary lead shielding. Lumbar spine CT delivers some 3.5 rads. Acting on anxiety attributed by some to physician advice, women have opted for pregnancy termination after receiving low-dose diagnostic radiation during early gestation (Ratnapalan et al., 2008). Iodinated contrast media used for radiological procedures has the potential to depress fetal thyroid production. Most states mandate routine newborn thyroid screening; this is especially important in infants receiving iodinated contrast agents in utero.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used selectively to scan the brain and the venous and arterial circulations and is useful during pregnancy. No study or clinical observation has detailed harmful effects to mother or child, but detailed longitudinal studies on children exposed in utero to MRI are lacking. Despite the observations by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American College of Radiology (ACOG, 2004; American College of Radiology Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media, 2004; Kanal et al., 2007) that there is no known adverse effect of MRI on the fetus, only two human studies on this point exist, neither of which was of a design adequate to detect adverse effects that may be significant (International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection, 2004). Restriction of maternal brain MRI, especially during the first trimester, is prudent.

Fortunately, most MRI studies relevant to neurological disease do not require the use of gadolinium. However, definitive studies detailing the safety of gadolinium-based magnetic resonance contrast agents during pregnancy and lactation are lacking. Gadolinium crosses the placenta, finds its way into amniotic fluid, and is swallowed by the fetus. Fetal developmental delay occurs in animals receiving high doses of gadolinium. No reports of mutagenic and teratogenic effects in humans appear in reviews of available literature. A small prospective study of 26 women who received gadolinium inadvertently during the periconceptional period and first trimester yielded a single child with a minor congenital anomaly (De Santis, 2007). Some authorities recommend that a woman abstain from breastfeeding for 24 hours after receiving iodinated contrast agents including gadolinium (Tang et al., 2004). Others, citing the tiny amount of contrast entering breast milk and the minute amount absorbed from the baby’s gut suggest that the potential risks are insufficient to warrant a recommendation to interrupt breastfeeding (Chen et al., 2008; Webb et al., 2005).

Headache

Tension Headache

Headache during pregnancy is common. Usually a patient visits the neurologist to receive reassurance that no serious medical problem is apparent. Of the headaches that occur during pregnancy, benign tension headaches are seen most often (see Chapter 69). No known association exists with hormones and, specifically, no association with the hormonal changes of pregnancy. Treatment for mild headaches often includes behavioral therapy, adequate rest, moist heat, massage, exercise, avoidance of triggering factors, and use of acetaminophen. For severe headaches, the use of a tricyclic antidepressant such as amitriptyline or nortriptyline may be helpful. No evidence of embryopathy occurs with amitriptyline, and preschool children exposed in utero to tricyclic antidepressants have normal global IQs, language, and behavioral development. Fluoxetine may cause uncommon but serious fetal risks (Chambers et al., 2006; Diav-Citrin et al., 2008; Mills, 2006).

Migraine Headache

More than 80% of women with migraine clearly show improvement during pregnancy, but 15% continue to have headaches, and in 5% headaches worsen. The prognosis for women with migraine without aura is better than that for women with migraine with aura. Headaches were more likely to persist with diagnosed menstrual migraine, hyperemesis, or a “pathological pregnancy course” in a prospective study. For women anticipating pregnancy, the physician may discontinue or reduce the dose of all migraine medications to lower the risk of possible fetal damage and offer vigorous treatment with behavioral therapy, moist heat, and the judicious use of acetaminophen or opioid preparations. Migraine usually lessens during the second and third trimesters. The diagnosis of complicated migraine or de novo migraine with aura during pregnancy requires a thorough consideration of other diagnoses. Migraine may increase the risk for preeclampsia, especially for patients with prepregnancy obesity (Adeney et al., 2005) and may increase the risk for peripartum stroke (James et al., 2005). While small increased incidences of low birth weight, preterm birth, and cesarean section were noted in an Asian population (odds ratios 1.16, 1.24, and 1.16, respectively), the single large study did not control for the use of medications in this population, where the authors note equivocal clarity in the database diagnosis of migraine (Chen et al., 2010).

Before Pregnancy

Pregnancy and the anticipation of pregnancy complicate usual migraine therapy. Valproic acid causes fetal malformations. For fertile women taking prophylactic valproic acid whose migraine has been poorly responsive to other therapy, folic acid supplementation has been advised (see Epilepsy and Its Treatments). Discussion of reliable contraceptive measures and the risks for fetal malformation is essential. During pregnancy, physicians advise avoidance of valproic acid to treat headache. Topiramate is fetally toxic in animals, and the magnitude of teratogenic risk of topiramate is undetermined in humans. In older studies, approximately 50% of pregnancies were unplanned. When prescribing these medications, unintended fetal exposure during the early first trimester may occur.

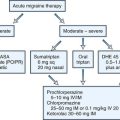

During Pregnancy

During pregnancy, ergotamine and dihydroergotamine cause high rates of fetal malformation and are contraindicated. For newer drugs such as triptans, data are incomplete and their general use is inadvisable. Limited information suggests a low or no teratogenic potential (Kurth and Hernandez-Diaz, 2010). This reassuring but qualified news has emboldened some to suggest that prescription of a triptan may be acceptable in pregnant women who suffer physiologically and psychologically disabling migraine, whose headaches respond to a triptan, and in whom safer medications have failed (Von Wald and Walling 2002). Other authors offer that opioids and antiemetics, specifically prochlorperazine (oral or suppository), are drugs of choice for migraine during pregnancy (Goadsby et al., 2008). Metoclopramide, acetaminophen, and meperidine do not increase fetal risk and may be of benefit.

Postpartum

Breastfeeding reduces migraine recurrence (Sances et al., 2003). In general, the breastfeeding woman with migraine should avoid ergotamine and lithium. Cautious use of triptans and antidepressants is acceptable. One article suggests that “In the absence of a specific contraindication such as coronary or cerebrovascular disease, sumatriptan by injection is an ideal way to deal with disabling migraine in this period, even for breastfeeding women” (Goadsby et al., 2008).

When a woman presents with severe puerperal headache, physicians may derive some comfort that 34% of women with a history of migraine will develop headache during the first postpartum week, commonly between 4 and 6 days and usually benign. However, the puerperium also is the time serious illness may present with sudden severe or “thunderclap” headache (see Chapter 69). The differential diagnosis includes migraine, cerebrospinal fluid hypovolemia including postdural puncture headache, CVT, preeclampsia/eclampsia, subarachnoid hemorrhage, stroke syndromes, posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome, postpartum cerebral angiopathy, pituitary apoplexy, Sheehan syndrome, and lymphocytic hypophysitis (Gladstone et al., 2005).

Myasthenia Gravis

Before Pregnancy

Fertility is unaffected by myasthenia gravis, and oral contraceptive agents do not weaken these patients. No single study offers certainty with regard to the cumulative risk pregnancy causes in the patient with known myasthenia gravis (Hoffman et al., 2007). Conditions may remain stable, improve, worsen, or both improve and worsen at different stages of pregnancy. Approximately two-thirds of patients report some worsening at some time during pregnancy or the puerperium. The puerperium and first trimester are times of greatest risk. The course of myasthenia gravis for a future pregnancy is not predictable by the course of previous pregnancies.

Pregnancy Outcome

A retrospective Norwegian study reported an increased risk for premature rupture of amniotic membranes and double the rate of cesarean section among myasthenic women (Hoff et al., 2003). A smaller retrospective Taiwanese study found statistically insignificant increased risk of cesarean section, infants small for gestational age, low birthweight, and no difference for preterm delivery (Wen et al., 2009). Premature labor may be more common in women with myasthenia gravis but varies considerably among multiple studies.

Perinatal mortality increases to 6% to 8% for infants of women with myasthenia gravis, which is approximately five times that of the normal population. Approximately 2% of these are stillborn. Transient neonatal myasthenia affects 10% to 20% of infants born to women with myasthenia gravis. Most infants who develop transient myasthenia gravis do so within the first day, but weakness may begin up to 4 days after delivery and usually resolves within 3 to 6 weeks. Neonates require careful observation for at least 4 days. An imperfect correlation exists between maternal levels of antiacetylcholine receptor antibodies and the likelihood that the neonate will develop transient myasthenia gravis. Intrauterine exposure to receptor antibodies rarely may result in arthrogryposis, which has a high likelihood of recurrence in future pregnancy. The role of intragestational plasmapheresis and immunosuppression to prevent this condition in subsequent pregnancies is unknown (Polizzi et al., 2000).

Disorders of Muscle

Myotonic Dystrophy

Half of children born to women with myotonic dystrophy inherit the disorder. Anticipation due to an increased number of triplet repeats (see Chapter 40) is responsible for the syndrome of congenital myotonic dystrophy in the neonate (see Chapter 79). Many neonates are hypotonic, and reported rates of morbidity are high. Fetal myotonic dystrophy may affect fetal swallowing, causing polyhydramnios. Prenatal diagnostic testing with amniocentesis or chorionic villus biopsy is available.

Available data suggest that myotonic dystrophy type 2 (see Chapter 79) is more benign than type 1 and may not result in problems with general anesthesia or increase problems of delivery for the pregnant woman. Type 2 may not increase the risk for polyhydramnios or stillbirth or result in congenital myotonic dystrophy (Day et al., 2003). Another study noted that about 21% in their series first presented with myotonic weakness during pregnancy, which worsened during subsequent pregnancies (Rudnik-Schöneborn et al., 2006). Some 17% of patients miscarried, half experienced preterm labor, and 27% delivered preterm.

Inflammatory Myopathy

Pregnancy worsens or activates polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Manifestations of collagen vascular disease commonly associated with myositis may complicate pregnancy. More than half of fetuses die, but surviving infants thrive. Immunosuppressive treatment is advisable for gravid women. In small studies, decreased activity of myositis correlates with a more favorable outcome for the fetus (Silva et al., 2003; Váncsa et al., 2007).

Neuropathy

Bell Palsy

Facial nerve palsy occurs three to four times more commonly during pregnancy and the puerperium, usually occurring at about 35 weeks’ gestation (Shmorgun et al., 2002). However, reanalysis of these data suggests that this conclusion may be inaccurate, and the frequency of Bell palsy may be about the same in women of childbearing age (Vrabec et al., 2007). A retrospective chart review found the prognosis for recovery of facial nerve function to be worse when facial palsy occurs during pregnancy (Gillman et al., 2002) but not usually when the severity of the facial palsy is mild. Researchers find increased frequency of toxemia and hypertension in patients with gestational facial palsy and recommend careful and continued monitoring of the affected woman for these conditions. Herpes simplex virus type 1 is the cause of most facial palsies, and varicella-zoster far less often. Pharmacological therapy of Bell palsy during pregnancy remains controversial. When begun within 3 days of onset of facial weakness, prednisone 1 mg/kg for 5 days, tapering rapidly over a total 10-day course, may be effective in improving the prognosis in nongravid adults and is considered safest when not used during the first trimester (Vrabec et al., 2007). The routine use of antiviral drugs simultaneously has not been proven unequivocally effective in nongravid adults in the absence of a varicella-zoster syndrome (Ramsay Hunt syndrome or zoster sine herpete), including a meta-analysis (Browning, 2010; Quant et al., 2009). This combination of drugs has not been tested adequately during pregnancy. Individually, the drugs pose low risk. Patching of the eye and lubricating eye drops may help prevent corneal irritation (see Chapter 70).

Low Back Pain

Low back pain is ubiquitous in the nongravid female population and increases during pregnancy. In retrospective questionnaires, researchers find more than half the pregnant population recall pain during their pregnancy and half of those women remembered radiation of the back pain to the extremeties (Fast et al., 1987). As many as three-quarters of pregnant women report low back pain at some time in their pregnancy in prospective studies (Pennick and Young, 2008). A careful, prospective study estimated the prevalence of “true” sciatica, radiation of the pain in a dermatomal distribution to be less than 1% (Ostgaard et al., 1991). Investigators blame this torment and its propensity to increase after the fifth month of pregnancy on increasing lumbar lordosis, direct pressure from the enlarging uterus, postural stress, and hormonally-induced ligamentous laxity. In one Swedish study, nearly all women experiencing back pain during pregnancy serious enough to provoke loss of work suffered recurrence of back pain in a subsequent pregnancy and low back pain recurred commonly in the nongravid state (Brynhildsen et al., 1998). MRI and electromyography (EMG) can be helpful rarely. Risks of EMG are negligible. Authorities advise avoiding muscles that bring the EMG needle too close to the developing fetus. Risks of MRI are known incompletely (see Imaging, earlier). An extensive review of the literature concluded that interventions for the treatment of the low back pain of pregnancy are biased enough that unequivocal therapeutic direction cannot be indicated. The efficacy and risk of techniques to prevent low back pain are unknown. Studies of specifically tailored strengthening exercise, sitting pelvic tilt exercise programs and water gymnastics all reported beneficial effects. The effect of physiotherapy is small but may be of some benefit as may be acupuncture. Studies on acupuncture claim better results than for physiotherapy (Pennick et al., 2008).

When minor neurological deficits accompany a syndrome suggesting compressive disc disease, authorities recommend a conservative approach based on limited case series (Laban et al., 1995). Surgical management for compressive disc disease has been successfully employed and is suggested during pregnancy to treat severe or progressive neurological deficits and in the presence of a cauda equina syndrome (Brown and Levi, 2001; Laban et al., 1995).

We lack studies or consensus agreement on the preferred mode of delivery for patients with herniated and symptomatic lumbosacral disc disease. Laban et al., (1995) describes patients who underwent cesarean section successfully to avoid the theoretical increases of epidural venous pressure during the valsalva maneuver associated with pregnancy. This author suggests that a reflex response of skeletal muscle to pain during pregnancy may be responsible for elevated venous pressure, and that regional block anesthesia may be as effective with vaginal delivery.

Acute Polyradiculoneuropathy (Guillain-Barré Syndrome)

Pregnancy does not affect the incidence or course of acute polyradiculoneuropathy, but some investigators believe the pregnant patient may be more vulnerable to complications (Chan et al., 2004). Usually, infants of a mother without complications are born healthy. Only one case of neonatal acute polyradiculopathy resulting from maternal disease is reported. Some investigators recommend fluid loading before plasmapheresis to prevent hypotension. Others suggest avoidance of tocolytics in the presence of autonomic instability. IVIG has been used safely during pregnancy, but the number of patients who received this therapy and were studied remains small. Uterine contractions are unaffected by the disease. Cesarean section is only for obstetric indications. Severe hyperkalemia caused presumably by succinylcholine anesthesia resulting in reversible cardiac arrest has been described in a pregnant woman 3 weeks after complete recovery from acute polyradiculopathy (Feldman J.M., 1990). This case and additional related reports have prompted some authors to suggest that the combination of pregnancy and acute polyradiculopathy should lead to the cautious use or avoidance of depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents.

Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1

Small studies indicate that Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1 worsens in approximately half of affected women during pregnancy. The magnitude of the effect of pregnancy on this disease remains unclear. Risk is less when weakness begins in adult life. After delivery, this deterioration improves in a third of patients and becomes persistently progressive in two-thirds of patients, although studies vary in their observations (Swan et al., 2007). A retrospective Norwegian study found that affected women were twice as likely as the general population to have fetal-presentation anomalies, experience postpartum hemorrhage, and undergo cesarean section—commonly on an emergency basis. Forceps delivery occurred three times as often (Hoff et al., 2005). Epidural anesthesia for labor is safe.

Maternal Brachial Plexus Neuropathy

Hereditary brachial plexus neuropathy is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by periodic attacks of asymmetrical pain, weakness, atrophy, and sensory alteration of the shoulder girdle and upper limbs attributed to involvement of proximal upper-limb nerves or the brachial plexus. Symptoms are indistinguishable from those of Parsonage-Turner syndrome (see Chapter 29). Attacks may begin as early as 3 hours postpartum despite cesarean section, may recur for weeks following parturition, and may follow subsequent pregnancies. Intravenous methylprednisolone may reduce the pain but seems not to influence the course of the disease (Klein et al., 2002).

Movement Disorders

Restless Legs

Unpleasant paresthesias (described as creeping, crawling, aching, or fidgetiness) localized deep within both legs affect 10% to 27% of pregnant women. Usually they begin 30 minutes after the patient lies down and occur mainly in the last trimester. An irresistible desire to move the legs accompanies the discomfort. Symptoms resolve sharply during the first month postpartum, after which time about 5% of women remain affected. A study found lower average hemoglobin and mean corpuscular volume than in healthy subjects (Manconi et al., 2004). This same study describes gestational worsening in about 60% of patients reporting restless legs syndrome (RLS) before pregnancy, but improvement during pregnancy in some 12% of preexisting RLS. Approximately 80% of patients complaining of restless legs experience periodic movements of sleep (see Chapter 68). These stereotyped flexion movements of the legs during non–rapid eye movement sleep may awaken the patient, leading to sleep loss and excessive daytime somnolence. Caffeine ingestion, uremia, alcohol use, iron deficiency, hypothyroidism, vitamin deficiency, rheumatoid arthritis, peripheral neuropathy, and medications are important, if only occasional, associated factors. The importance of iron and folic acid supplementation remains unclear. Folic acid may be of benefit in treating restless legs during pregnancy. Anecdotal reports suggest a benefit from vitamin E, vitamin C, and magnesium supplements. Electric vibrators, stretching, walking, decreased activity, and massage also may be helpful. The use of dopaminergic agonists and levodopa to treat periodic limb movements of sleep during pregnancy has not undergone systematic study. Anecdotal reports indicate success and safety with levodopa. When a physician decides to offer either of these therapies, careful disclosure of the potential for known and also unforeseen risks to the fetus may allow the patient to make an informed decision.

Friedreich Ataxia

Little information about pregnancy and Friedreich ataxia is available. An author notes uneventful pregnancies in a retrospective study of 17 women without known adverse outcomes and recommends cardiac examination and cardiac monitoring during labor (Mackenzie, 1986). Studies point to medications such as magnesium sulfate, muscle blockers, and barbiturates as possibly problematic in isolated case reports, with cautious use of these medications recommended (Kranick et al., 2010).

Dystonia

Pregnancy carries no known additional risk to women diagnosed with dystonia. In one review, pregnancy was considered unlikely to exacerbate dystonic movement. When needed, botulinum toxin A, used with caution, seems preferable to baclofen (Kranick et al., 2010).

Rare case reports are the basis for dystonia gravidarum. This is a syndrome reported to begin during the first trimester and resolve by the end of the second trimester. Cervical dystonia and a horizontal head tremor characterized the case reported and may have been helped to some degree by clonazepam (Lim et al., 2006b).

Parkinson Disease

Rarely, patients suffering from Parkinson disease become pregnant. No reliable studies on the effect of pregnancy on the course of Parkinson disease or the effect of the disease on pregnancy are available. Information available from case reports is contradictory but indicates a possible adverse effect of pregnancy on the symptoms. No difficulty with pregnancy outcomes is known. Available limited data best supports the cautious use of l-dopa/carbidopa and the possible avoidance of amantadine during pregnancy (Kranick et al., 2010).

Tourette Syndrome

A study of 11 pregnancies in a mixed retrospective and prospective analysis found no unequivocal effect of pregnancy on the severity of tics in Tourette syndrome. The authors acknowledge the severe limitations of the study on a topic about which little information is otherwise available. The study also indicates the importance of this information for physicians treating patients whose tics worsen during pregnancy and for whom neurological consultation is requested (Stern et al., 2009).

Wilson Disease

Small case series provide limited information on which to base treatment decisions during pregnancy for women with Wilson disease. Pregnancy is contraindicated only in the presence of severe liver disease (Brewer et al., 2000). Pregnancy does not appear to have an adverse effect on the course of Wilson disease, but lack of treatment of the condition can. Anecdotal but numerous reports of women who stop therapy during pregnancy documents disease progression and maternal death. A study from India and the largest case series on pregnancy outcomes reported 59 pregnancies in 16 patients with 30 successful pregnancies, 24 spontaneous abortions, 2 medical terminations, and 3 stillbirths (Sinha et al., 2004). Most of the adverse outcomes occurred in patients with Wilson disease untreated during pregnancy. Presymptomatic patients with Wilson disease had excellent outcomes for their earlier pregnancies. Debate over the most effective and safest medication continues. Penicillamine and trientine are teratogenic in animals; zinc acetate is not. A recent review suggests an advantage of zinc acetate (Kranick et al., 2010), as do advocates of zinc therapy (Brewer et al., 2000). In a series in which zinc acetate was given during 26 pregnancies, 1 case of microcephaly and 1 cardiac defect were noted. The authors mention 4 miscarriages they chose not to include in the study analysis (Brewer et al., 2000).

Wernicke Encephalopathy

More than three-fourths of women experience nausea and vomiting during pregnancy, most commonly between 6 and 16 weeks’ gestation. When vomiting becomes severe enough to result in weight loss or metabolic derangement requiring intravenous therapy, the condition is termed hyperemesis gravidarum. Commonly, hyperemesis is isolated and idiopathic. Molar pregnancy, hyperthyroidism, and hepatitis are differential diagnostic considerations. Studies on treatment with vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), 10 mg 3 times daily for 5 days, showed little benefit, but enthusiasts continue to recommend this treatment, sometimes with ginger (Niebyl and Goodwin 2002).

Apathy, drowsiness, memory loss, catatonia, ophthalmoplegia, nystagmus, ataxia, optic neuritis, and papilledema may result individually or together, typically between 14 and 20 weeks’ gestation. These clinical features are emblematic of Wernicke encephalopathy (see Chapter 57). A subtle presentation can delay prompt diagnosis. This condition is sometimes associated with gestational polyneuropathy and central pontine myelinolysis. Exacerbating factors include persistence of the hyperemesis over at least 3 weeks and the administration of intravenous glucose without other nutrients.

Multiple Sclerosis

Uncomplicated multiple sclerosis (MS) has no apparent effect on fertility, pregnancy, labor, delivery, the rate of spontaneous abortions, congenital malformations, or stillbirths. The approximately 13% reduction in pregnancy rate among women with MS noted in one study may result from physical disability and from women deciding not to have children. Oral contraceptive agents do not affect the incidence of MS (Hernan et al., 2000). One study of a large U.S. national database noted marginally increased risk of fetal intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR; weight <10th percentile for gestational age) and rate of cesarean section. Calculated at 2.7%, the low rate of IUGR was 1.9 times more likely than the normal population. Physicians performed cesarean section at a higher rate: 42% for women with MS compared to 32.8% for controls. The study found no increase in other adverse obstetric outcomes. The authors acknowledge significant methodological concerns. Pregnancy outcome data were unavailable (Kelly et al., 2009).

Predicting the effect of pregnancy on the course of MS for an individual patient remains challenging. Prospective analysis clarifies that for research populations, MS does not worsen overall as a result of pregnancy and suggests that for the average fertile patient with MS, the overall rate of progression of disability from MS compared to the rate of progression 1 year before pregnancy does not change for some 21 months postpartum. The exacerbation rate of MS decreases during the last trimester and increases during the 3 to 6 months after parturition. Postpartum relapse correlated with, but was predicted poorly by, an increased relapse rate in the prepregnancy year, an increased relapse rate during pregnancy, and a higher level of disability at pregnancy onset (Vukusic et al., 2004).

Most investigators recommend discontinuing glatiramer acetate, interferon beta-1a, and interferon beta-1b before an anticipated pregnancy and recommend contraception for fertile women taking these agents. Human studies of interferons suggest the possibility of increased spontaneous abortion, fetal loss, and low birth weight, supplementing the reported abortifacient data for interferons in primates (Boskovic et al., 2005; Sandberg-Wollheim et al., 2005). This information is at odds with postmarket surveillance studies that report a rate of spontaneous abortion and other adverse fetal events no different than expected in a normal population (Coyle et al., 2003). In one small study, the rate of spontaneous abortion with the use of interferon beta-1b was higher than the normal population (28%) and higher than that of interferon beta-1a (Weber-Schoendorfer et al., 2009). A larger study suggests that early first trimester interferon-beta 1b exposure results in no increased risk of spontaneous abortion. Lower birthweight and length in exposed children did not result in significant fetal complications, malformation, or developmental abnormalities after a median follow-up of approximately 2 years (Amato et al., 2010).

Glatiramer acetate seems safer than interferons in animal studies, but these studies are incompletely generalizable to humans. We lack reliable information on pregnancy outcomes for women who take glatiramer acetate. One small study warns against the use of glatiramer acetate while describing the spontaneous abortion rate associated as “encouraging” (Wolfgang et al., 2008), and another that glatiramer acetate does not pose a major risk for developmental toxicity, stopping short of recommending its use during pregnancy (Weber-Schoendorfer and Schaefer, 2009).

Whether glatiramer acetate or the interferons are secreted in breast milk is unknown. Until more information is available with regard to safety, advise discontinuation of these medications while nursing. Breastfeeding women who start immunomodulating agents immediately postpartum have more relapses than those who remain untreated and breastfeed (Gulick et al., 2002). In a study of the use of IVIG postpartum, more women remained relapse free if they breastfed for more than 3 months (90% versus 71%) (Haas et al., 2007). Some researchers recommend that women breastfeed for at least 2 months postpartum before considering immunomodulating therapy (Langer-Gould et al., 2009), but others maintain that current data do not exclude a possibility that some MS patients may benefit from immunomodulating therapy (Airas et al., 2010). Currently the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends breastfeeding “for at least the first year of life and beyond for as long as mutually desired by mother and child” (Section on Breastfeeding, 2005).

Tumors

Primary Brain Neoplasms

Brain tumors of all types occur during pregnancy, but only at 38% of the rate expected in nonpregnant women of fertile age. Diminished fertility in women with these tumors may explain this reduction because pregnancy probably does not protect against the development of neoplasms. Studies show increased numbers of abortions before the symptoms of tumor appear. The effect of pregnancy on morbidity and mortality in women with brain tumors is not known, but certain tumors grow more rapidly during pregnancy (Pallud et al., 2009). Meningiomas have estrogen receptors, which may explain the enlargement usually seen during pregnancy. The rupture rate of spinal hemangiomas increases with the duration of gestation. Postpartum remission of symptoms of meningioma, vascular tumors, and acoustic neuromas may be due to tumor shrinkage.

Malignant tumors or tumors threatening compression of vital brain structures usually require surgery during pregnancy. During pregnancy, most neurosurgical procedures appear well tolerated (Cohen-Gadol et al., 2009). Surgery for some benign tumors can wait several weeks postpartum to observe for spontaneous improvements. Babies of most women with brain tumors deliver by cesarean section. Vaginal delivery is reserved for patients whose tumor would not pose a threat of herniation with the shifts of intracranial pressure associated with labor. Pregnancy interruption is considered when increased intracranial pressure, vision loss, or uncontrolled seizures develop as a result of the tumor. Some neurosurgeons presume the safety of intracranial carmustine implants to treat high-grade glioma during pregnancy, despite the lack of empirical evidence on safety for the fetus and known teratogenicity of systemic carmustine (Stevenson and Thompson, 2005).

Administration of corticosteroids commonly lessens symptoms of brain tumors (see Chapter 52D), but fetal hypoadrenalism may result from their use. Physicians usually defer potentially teratogenic chemotherapy until after delivery. Cranial radiation therapy during pregnancy may be helpful to the mother, but no dose of radiation is completely safe for the fetus. The fetus usually is seriously affected when it receives doses greater than 0.1 Gy (10 rads), which may cause growth retardation, microcephaly, and eye malformations. The fetus may also be affected by lower amounts of radiation, particularly early in gestation. Researchers estimate that in utero exposure to 0.01 to 0.02 Gy of radiation increases the incidence of leukemia by 1 case per 6000 exposed children. Estimates of the fetal dose during radiation for brain tumors range from 0.03 to 0.06 Gy. One study suggests that alternative positioning of the patient may reduce fetal exposure to as little as 0.003 Gy when a dose of 30 Gy is delivered to the brain (Magne et al., 2001).

Pituitary Tumors

Usually, women with pituitary tumors deliver vaginally. Studies have not demonstrated tumor growth associated with breastfeeding. Pituitary apoplexy may present within days, weeks, or occasionally years after delivery. Uncommonly, a pituitary mass presenting in late pregnancy or up to 1 year postpartum may be lymphocytic hypophysitis. Some researchers find MRI to be helpful in establishing the diagnosis and possibly reducing the need for neurosurgery (Gutenberg et al., 2009).

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension (Pseudotumor Cerebri)

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) (see Chapter 59) usually worsens with pregnancy. Some researchers advise a delay in pregnancy until all signs and symptoms of preexisting IIH abate. Termination of pregnancy is of unknown value and is not indicated. Healthy babies usually result regardless of whether IIH begins before or during pregnancy.

The use of acetazolamide remains controversial; human studies are inadequate to determine its efficacy or teratogenic potential. Nevertheless, acetazolamide has been used to treat IIH during many pregnancies productive of healthy infants. Some physicians recommend restricting its use until after 20 weeks’ gestation. A retrospective study of 12 patients taking acetazolamide 500 mg twice a day resulted in normal children (Lee et al., 2005).

Epilepsy and Its Treatments

Maternal Considerations

Women with epilepsy have approximately 15% fewer children than expected. Reasons offered for this decrease in fertility include social effects of epilepsy, menstrual irregularity, the effect of some antiepileptic medications on the ovaries, and an effect of seizures on reproductive hormones. In an Indian registry-based study, 38.4% of women with epilepsy were infertile. Researchers identified age, lower education, and polytherapy with antiepileptic medications as risk factors (Sukumaran et al., 2010).

A prospective Finnish study is more optimistic, suggesting that the frequency of seizures during gestation does not change or may even decrease (Viinikainen et al., 2006). The International Registry of Antiepileptic Drugs and Pregnancy (EURAP) reports that nearly 60% of women with epilepsy and careful monitoring do not have seizures during pregnancy (EURAP Study Group, 2006). A consensus statement and review of the evidence available concluded that there is insufficient evidence to determine whether gestation is associated with any predictable change in the frequency of seizures or status epilepticus reported in populations of women with epilepsy (Harden et al., 2009b).

Epilepsy does not affect the course of pregnancy to a clinically significant degree. Epilepsy either does not increase the rate of cesarean section or increases it only modestly (Kelly et al., 2009), has no effect on late-pregnancy bleeding, but may increase premature labor, premature contractions, or premature delivery to a small degree, primarily in women who smoke tobacco. While the effect of epilepsy on the rate of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or spontaneous abortion is uncertain, in one carefully conducted study, researchers found no increased risk for preeclampsia (Harden et al., 2009b; Viinikainen et al., 2006).

Fetal Considerations

Nearly 90% of epileptic women deliver healthy, normal babies. However, risks for miscarriage, stillbirth, prematurity, developmental delay, smallness for gestational age, and major malformations are increased in the offspring of epileptic mothers. Available literature suggests that there is no increase in perinatal mortality. Maternal seizures, AEDs, and socioeconomic, genetic, and psychological aspects of epilepsy affect outcome. Although AEDs may cause significant problems for the fetus, the consensus among neurologists has been that maternal seizures probably are more dangerous. Convulsive seizures cause fetal hypoxia and acidosis and are associated with the potential for blunt trauma to the fetus and placenta (Holmes et al., 2001). Fetal heart rate slows during and for up to 20 minutes after a maternal convulsion, which suggests the presence of fetal asphyxia. The child of an epileptic mother experiencing convulsions during gestation is twice as likely to develop epilepsy as the child of a woman with epilepsy who does not have a convulsive seizure during gestation. A retrospective study identified five or more generalized convulsive seizures during gestation as an independent risk factor for lowered verbal IQ scores in children (Adab et al., 2004). Pregnant women may be reassured that current data do not indicate an increased risk for malformation to their fetus from an uncomplicated single seizure during the first trimester.

A prospective study in which clinicians physically examined children of epileptic mothers and controls (Holmes et al., 2001) reported the frequency of major malformations (structural abnormalities of surgical, medical, or cosmetic importance not including microcephaly, growth retardation, or hypoplasia) to be 1.8% in their normal control population. With one AED (phenytoin, carbamazepine, or phenobarbital) this rate rose to 3.4% to 5.2%, and with two or more to 8.6%. Some women with a history of seizures did not take anticonvulsants during pregnancy and had a rate of major malformation statistically the same as the control population at 0%. Women who suffered seizures during the first trimester and were taking their anticonvulsant drugs had a rate of major malformation of 7.4% to 7.8%. This carefully gathered information lays blame for teratogenesis primarily on the use of AEDs.

Studies of various design suggest that valproic acid causes a higher rate of teratogenicity than other commonly used AEDs. Increased risk may be related to increasing dose of valproic acid and was 9.1% for higher valproic acid doses in one study (Morrow et al., 2006). Higher-dose lamotrigine (>200 mg/day) also possibly increased teratogenicity up to 5.4% (Brodie, 2006). Based on these trends, some researchers have suggested caution in the use of AEDs, particularly valproic acid, in treating fertile women with epilepsy and avoidance of this medication during the first trimester if possible.

Adequate human studies of newer anticonvulsant drugs during pregnancy are lacking. The teratogenic potential of gabapentin, vigabatrin, tiagabine, zonisamide, topiramate, clobazam, levetiracetam, lacosamide, and oxcarbazepine is incompletely understood. A consensus statement on outcomes (Meador et al., 2008) concluded that the risk of fetal malformations with newer AEDs is “largely unknown, and consequences to individual offspring could be severe and lifelong.” At this time, the physician may consider reevaluating the need for these anticonvulsants in a patient planning pregnancy or substituting an agent with known potential risks.

Several studies focused on cognitive effects of AEDs employed during pregnancy. Holmes and colleagues (2000) described normal behavior in children of women with epilepsy on no AEDs during gestation, compared to matched controls. Vinten et al. (2005) found that children exposed to valproic acid in utero have significantly lower verbal IQ scores and memory function than children exposed to carbamazepine or phenytoin. While contradictions exist in published literature, the effects of carbamazepine and phenytoin may have little effect on cognition, but methodological problems hinder these analyses. A small United Kingdom pregnancy registry study compared use of valproic acid (mean dose 800 mg) and levetiracetam (mean dose 1700 mg) taken throughout pregnancy to a control group. Assessing development in children less than 2 years of age, 8% who were exposed to levetiracetam fell within the below average range, while the corresponding statistic was 40% for valproic acid, and 12% born to control mothers (Shallcross et al., 2011). Larger-scale prospective studies are needed to adequately quantify the cognitive effect of in utero AED exposure.

Common Advice and Management Strategy

The need for AED therapy should be reevaluated before conception. Once pregnancy has begun, discontinuing medications becomes more problematic. A supplement to a practice parameter from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) states: “Although many of the recommendations in this parameter suggest minimizing AED exposure during pregnancy, for most women with epilepsy, discontinuing AEDs is not a reasonable or safe option” (Harden et al., 2009c). Whether this approach may be helpful for selected patients is not addressed.

Physicians often monitor and adjust serum AED concentrations with increased frequency during gestation and the postpartum period. However, we lack data demonstrating the effectiveness of such a plan. Some reviewers observe that lamotrigine levels drop more commonly during pregnancy and suggest that if there is a benefit to increased attention to AED levels, lamotrigine therapy might be most deserving of scrutiny. A review of available literature associated with a practice parameter (Harden et al., 2009a) provides a recommendation that monitoring of lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and phenytoin levels are a consideration, while monitoring levetiracetam and oxcarbazepine are discretionary.

Carbamazepine should be weaned in women with a family history of neural tube defects, particularly if there is a suitable substitute. A consensus statement published by the AAN recommended that for a fertile woman taking valproic acid as monotherapy for epilepsy, avoidance of valproic acid may be considered during the first trimester, but when valproic acid is taken as part of epilepsy polytherapy, avoidance of valproic acid should be considered (Harden et al., 2009c).

In one study, women taking AEDs and a multiple vitamin supplement containing folic acid had no reduction in the risk to their infants for developing cardiovascular defects, oral clefts, or urinary tract defects compared with women who took no supplements (Hernandez-Diaz et al., 2000). One detailed review found “insufficient published information to address the dosing of folic acid and whether higher doses offer greater protective benefit” (Harden et al., 2009a). These reviewers concluded that offering women with epilepsy supplements of at least 0.4 mg of folic acid before pregnancy “may be considered.” A review of similar data recommended folic acid 0.4 to 0.8 mg for all women capable of or planning pregnancy (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2009).

A deficiency of vitamin K–dependent clotting factors occurs in some neonates born to women who take phenobarbital, primidone, carbamazepine, ethosuximide, or phenytoin. Although rarely reported, neonatal intracerebral hemorrhage may be attributable to a vitamin K deficiency. In an attempt to lower this risk, some physicians prescribe oral vitamin K1 10 to 20 mg daily beginning 2 to 4 weeks before expected delivery and until birth. The American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended that physicians inject every newborn with 1 mg of vitamin K1 intramuscularly. When hemorrhage occurs, fresh frozen plasma corrects the hemorrhagic state acutely. A study by Kaaja and colleagues (2002) could not support the hypothesis that maternal enzyme–inducing AEDs increase the risk for bleeding in offspring. A literature review finds inadequate evidence to determine whether the newborns of women with epilepsy taking AEDs have an increased risk of hemorrhagic complications (Harden et al., 2009a). An accompanying practice parameter noted insufficient evidence to support or refute a benefit of prenatal vitamin K supplementation (Harden et al., 2009b).

Cerebrovascular Disease

Intracranial Hemorrhage

Women presenting with pregnancy-associated stroke are as likely to have an infarct as an intracerebral hemorrhage. Compared with the nonpregnant state, intracerebral hemorrhage occurs 2.5 times more often during pregnancy and almost 30 times more often during the 6 weeks postpartum. Up to 44% of these hemorrhages are associated with eclampsia and preeclampsia. In France, nearly half of women with intracerebral hemorrhage associated with eclampsia die. Additional diagnostic considerations include bleeding diatheses, cocaine toxicity, bacterial endocarditis, sickle cell disease, moyamoya disease, and metastatic choriocarcinoma. In approximately one-third of patients who have intracerebral hemorrhage, no specific cause is uncovered. The frequency of intracranial hemorrhage and its contributing causes is different in different populations (Jeng et al., 2004).

Ischemic Stroke

Most women who have a stroke before gestation complete uneventful pregnancies with excellent outcomes (Coppage et al., 2004). A Chinese study found no difference in fetal outcomes when strokes occurred during pregnancy (Kang and Lin, 2010). Women in whom emboligenic cardiac disease, SLE, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, or other coagulopathies have the added risk for stroke during pregnancy associated with those conditions. Stroke during one pregnancy by itself is not a risk factor for stroke in subsequent pregnancies. A review of a U.S. national database found a stroke risk per 100,000 deliveries of 34.2 (9.2 for ischemic stroke, 8.5 for cerebral hemorrhage, 0.6 for CVT, and 15.9 for the category of “pregnancy-related cerebrovascular event”) excluding subarachnoid hemorrhage. This same study suggests that the risk for gestational and peripartum stroke increases among women diagnosed with migraine, thrombophilia, SLE, heart disease, sickle cell disease, hypertension, thrombocytopenia, age over 35, being African American, and patients receiving blood transfusions (James et al., 2005). Cesarean delivery and gestational hypertension place women at increased risk for stroke.

Transitory neurological symptoms and preeclampsia are common during the pregnancies and puerperia of women with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). For these women, there is no difference in the miscarriage rate, mode of delivery, neonatal birth weight, or Apgar score (Roine et al., 2005).

Two-dimensional echocardiography may be the test of greatest importance when evaluating a woman with gestational stroke. CT and selective angiography are associated with a small risk to the fetus and require adequate shielding and hydration. The lack of X-irradiation may make magnetic resonance angiography preferable to selective angiography in the diagnosis of aneurysm, AVM, arteritis, venous thrombosis, or vasospasm (see Imaging, earlier).

Thrombolytic therapy for stroke during pregnancy seems unimpressive and has theoretically significant but unexplored potential risks for the fetus (Murugappan et al., 2006). Researchers trumpet a first case of clinical improvement associated with use of a thrombolytic agent (urokinase) during the immediate postpartum period (Méndez et al., 2008).

Cardiac Disease and Anticoagulation

Attempts to resolve the most pressing issue of anticoagulation in women with mechanical heart valves have been unsatisfactory. The reported risk for thromboembolism of some mechanical valve prostheses during pregnancy is 25% to 35%, much higher than the annual risk in the nonpregnant state of about 1.25% to 5.4%. In the nonpregnant state, target values for warfarin therapy and the use of aspirin 80 to 100 mg/day vary, depending on whether the valves are caged ball, tilting disk, or bileaflet. Aortic or mitral valvular location, the presence of atrial fibrillation, left atrial size, or thrombus, and previous thromboembolic episodes also influence some recommendations for anticoagulation (Stein et al., 2001). Conflicting data and incomplete studies impede attempts to translate these recommendations for the pregnant patient.

One systematic review and pooling of literature on fetal outcome for women with mechanical heart valves suggests that warfarin embryopathy occurs in 6.4% of live births when using warfarin throughout pregnancy (Chan et al., 2000). A logical therapeutic alternative to warfarin during pregnancy is heparin. Heparin does not cross the placenta and is not associated with teratogenic effects. The substitution of unfractionated heparin for warfarin at or before 6 weeks’ gestation eliminates the risk for warfarin embryopathy but increases the risk for thromboembolic complications over warfarin alone. Regardless of anticoagulant therapy, maternal mortality is approximately 3%, and fetal wastage is 16.3% to 44.4%. Additional carefully controlled studies are needed to clarify the validity of these data.

Some investigators recommend counseling against pregnancy for patients with mechanical heart valves who require warfarin. When a patient is pregnant, aggressive use of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin can be used throughout pregnancy. Other investigators suggest substituting unfractionated or LMWH for warfarin during 6 to 12 weeks’ gestation. During the 13th week, warfarin may be introduced and heparin discontinued. At the middle of the third trimester or at about 36 weeks, discontinue warfarin. Heparin may be given optionally until just before early induction of labor or cesarean section. Some European experts, based on a belief that the risks of warfarin are overstated, recommend use of warfarin throughout pregnancy (Verstraete et al., 2000). In the United States, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration categorizes warfarin as possessing fetal risk “which clearly outweighs any possible benefit to the patient (USFDA Category X).”

On the basis of limited evidence, a consensus statement from the American Stroke Association and the American Heart Association recommends that: “For pregnant women with ischemic stroke or TIA and high-risk thromboembolic conditions such as hypercoagulable state or mechanical heart valves, the following options may be considered: adjusted-dose UFH throughout pregnancy, for example, a subcutaneous dose every 12 hours with monitoring of activated partial thromboplastin time; adjusted-dose LMWH with monitoring of anti-factor Xa throughout pregnancy; or UFH or LMWH until week 13, followed by warfarin until the middle of the third trimester and reinstatement of UFH or LMWH until delivery (Class IIb; Level of Evidence C). In the absence of a high-risk thromboembolic condition, pregnant women with stroke or TIA may be considered for treatment with UFH or LMWH throughout the first trimester, followed by low-dose aspirin for the remainder of the pregnancy (Class IIb; Level of Evidence C),” (Furie et al., 2011).

Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome

The broad range of therapies offered as consensus recommendations for these patients, including those who have suffered stroke, underline the need for additional investigation in this area (Bates et al., 2004; Lim et al., 2006a; Tincani et al., 2004). Women with antiphospholipid antibodies and monosymptomatic habitual pregnancy loss should receive subcutaneous high-dose UFH together with low-dose aspirin until 34 weeks’ gestation. A combination of low-dose aspirin and LMWH during pregnancy appears to be current practice in the United Kingdom (Shehata et al., 2001) for women with antiphospholipid antibodies and a history of fetal loss after 16 weeks’ gestation, intrauterine growth retardation, early-onset preeclampsia, placental abruption, or stillbirth.

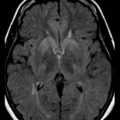

Postpartum Stroke

Debate continues over classification of syndromes described as postpartum cerebral angiopathy, delayed peripartum vasculopathy, reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, or postpartum stroke. These patients present with puerperal focal neurological signs and symptoms, often with headache, and have hypertension without edema or proteinuria. Brain MRI scanning depicts ischemia primarily in the parieto-occipital region, and angiography commonly demonstrates vasospasm. The course often is benign, but permanent deficits may occur. When these occurrences include headache, altered sensorium, seizures, or visual loss without hemorrhage, consider the possibility of a reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (RPLS). Other authors might suggest the diagnostic consideration of a reversible segmental cerebral vasoconstriction (RSCV) syndrome (see Chapter 51F), particularly when vasospasm demonstrated by arteriography involves large blood vessels within the circle of Willis (Singhal et al., 2009). Patients have been treated with calcium channel antagonists, corticosteroids, and antihypertensive medication. Some researchers believe postpartum stroke is a form of eclampsia/preeclampsia and suggest relaxation of requirements for diagnosis of eclampsia/preeclampsia.

Primary angiitis of the central nervous system presenting with stroke is less commonly associated with pregnancy than the cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes noted. It is associated with milder headache or none at all, but with abnormal cerebrospinal fluid in 80% to 90% of patients with pleocytosis and elevated protein. Confirmation is through biopsy and less commonly through diagnostic arteriography, which may have difficulty visualizing the disease of the small blood vessels that characterizes this condition. Prompt treatment with cyclophosphamide and prednisone is recommended (Birnbaum et al., 2009).

In one case series, Witlin et al. (2000) characterized postpartum stroke as an uncommon and unpreventable complication of pregnancy. After excluding trauma, neoplasm, infection, or eclampsia, they described women suffering ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke without specific warning; hemorrhage may follow initial ischemia with injury to blood vessel walls. In general, these events were most common around the eighth day after delivery (range 3-35 days) and were associated with cesarean delivery. Seizures in half of these patients, an increase in mean arterial pressure to 1.5 times above baseline, and headache heralded the onset. Two of 20 patients died of severe intracerebral hemorrhage. Included in this series were patients with CVT and a ruptured AVM. The investigators postulated that the hypercoagulable or thrombophilic state of pregnancy may emerge as a major risk factor, perhaps interacting with underlying coagulopathies.

Cerebral Venous Thrombosis

CVT has been associated with hypercoagulable states, infection, sickle cell disease, dehydration, and ulcerative colitis, in addition to gestation. Women diagnosed with peripartum CVT have no known increased risk for CVT in subsequent pregnancies (Mehraein et al., 2003). Differential diagnoses include eclampsia, meningitis, and cerebral mass. A large Swedish cohort study indicated that CVT was the most common cerebrovascular disorder of women in the period between 2 days before and 1 day after delivery. The standardized incidence rate ratio increased about 115-fold for CVT, 95-fold for intracerebral hemorrhage, 47-fold for subarachnoid hemorrhage, and 34-fold for cerebral infarction. Rates between 2 days post delivery and 6 weeks postpartum continued elevated: 15-fold for CVT, 12-fold for intracerebral hemorrhage, 8.3-fold for cerebral infarction, and 1.8-fold for subarachnoid hemorrhage (Salonen Ros et al., 2001).

Geographic location influences the frequency of CVT. India reports a high rate of puerperal CVT, estimated at 400 to 500 per 100,000 births. This high rate is primarily attributable to dehydration and has a predilection for women delivering at home. Incidence in the United States is comparatively low, approximately 9 per 100,000 deliveries. CVT associated with pregnancy is relatively more benign than that occurring without pregnancy. Researchers in Mexico describe a mortality rate of approximately 10% for gestational CVT and 33% for CVT not associated with pregnancy. In the United States, estimates of the mortality rate of CVT from all causes suggest that approximately 1 of 10 patients dies. However, death did not occur in a national survey of 4454 patients with peripartum CVT in the United States. Cesarean section and age older than 25 are risk factors for CVT, while preeclampsia and eclampsia are not (Cantu-Brito et al., 2010).

Eclamptic Encephalopathy

Preeclampsia (toxemia gravidarum) and eclampsia remain the principal causes of maternal perinatal morbidity and death. Edema, proteinuria, and hypertension after 20 weeks’ gestation characterize the syndrome of preeclampsia. Epileptic seizures and this preeclamptic triad comprise the syndrome of eclampsia. Defining the terms preeclampsia and eclampsia in this way simplifies a complex disorder. Important and common manifestations such as hepatic hemorrhage, disseminated intravascular coagulation, abruptio placentae, pulmonary edema, papilledema, oliguria, headache, hyperreflexia, hallucinations, and blindness seem relatively neglected in this definition. Occasionally, eclamptic seizures may precede the clinical triad of preeclampsia. Reasoning that pedal edema is ubiquitous and nonspecific during pregnancy, a consensus group recommended that physicians exclude edema as a criterion for the diagnosis of preeclampsia and concluded that the dyad of hypertension and proteinuria is sufficient, more sensitive, and no less specific (National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group, 2000).

Preeclampsia develops in approximately 4% to 8% of pregnancies in prospective studies. Eclampsia accounts for nearly half of intracranial hemorrhages and nearly half of cerebral infarcts in pregnancy and puerperium in French hospitals. In the United States, the figures are lower (14% and 24%, respectively). Methodological problems plague these studies, and accurate estimates are difficult to obtain. Neurological symptoms are more likely when the onset of eclampsia is postpartum. Maternal morbidity and mortality increase when eclampsia occurs at 32 weeks’ gestation. Preeclampsia increases the risk for stroke occurring over 42 days postpartum by about 60% (Brown et al., 2006). In Mexico, preeclampsia and eclampsia are not risk factors for developing cerebral venous thrombosis (Cantu-Brito et al., 2010).

A specific laboratory test for this disorder is lacking, and understanding of the pathogenesis remains incomplete. Conditions considered to place women at added risk for preeclampsia include multifetal gestations, previous preeclampsia, diabetes mellitus, hypercoagulable states, advanced age, dyslipidemia, microalbuminuria, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, obesity, and chronic hypertension. While some studies indicate increased risk of fetal growth restriction, spontaneous abortion, ectopic pregnancy, placenta previa, and fetal death in women who smoke during pregnancy, several studies paradoxically suggest that smoking reduces the risks of eclampsia and gestational hypertension (Yang et al., 2006).

Geneticists associate preeclampsia with a molecular variant of the angiotensinogen gene and suggest a possible genetic predisposition. Some researchers postulate that damage to the fetal-placental vascular unit (e.g., defective placentation) may release products toxic to the endothelium, causing diffuse vasospasm and organ injury. Researchers point to soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1), a substance produced in toxic amounts by the placenta and implicated in reducing levels of angiogenic trophic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor. Lack of these trophic factors may result in the clinical and pathological syndrome of preeclampsia. Short intervals between pregnancies reduce the risk for preeclampsia (Skjaerven et al., 2002). No theory satisfactorily explains the tendency for preeclampsia or eclampsia to affect primarily young primigravid women.

Women diagnosed with preeclampsia require careful fetal monitoring (ACOG, 2002). When preeclampsia is severe or hypertension is more than mild (systolic pressure of 160 mm Hg or diastolic pressure of 105-110 mm Hg), consensus groups recommend methyldopa and labetalol as appropriate first-line therapies. Hydralazine is used commonly.

Severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, or HELLP syndrome requires definitive therapy. Commonly, delivery is required within 24 to 48 hours of presentation, and all gestational products are removed from the uterus by vaginal or cesarean delivery. Experts offer plans of expectant management for women able to tolerate additional time to allow fetal lung maturation and stabilization before delivery (Haddad and Sibai, 2005; O’Brien and Barton, 2005).

Low-dose aspirin therapy was effective in preventing eclampsia in small trials, but larger studies of women at high risk for preeclampsia showed no benefit for aspirin 60 mg taken daily. French researchers claimed beneficial effects for aspirin 100 mg daily when doses are given by about 17 weeks’ gestation. Women whose bleeding time increased were more likely to benefit (Dumont et al., 1999). A meta-analysis concluded that use of antiplatelet agents results in a relative risk reduction of about 10% for preeclampsia, for delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, and for having a pregnancy with a serious adverse outcome (Askie et al., 2007). The combination of aspirin with ketanserin, a selective serotonin-2 receptor blocker, may prevent preeclampsia in women with hypertension diagnosed before 20 weeks’ gestation. However, consensus has not endorsed the use of aspirin with or without ketanserin or dipyridamole to prevent preeclampsia.

Researchers found that offspring of preeclamptic women born in Helsinki, Finland, between 1934 and 1944 suffered an almost doubled risk for stroke during adulthood (Kajantie et al., 2009). In Denmark, offspring of preeclamptic women have an increased risk of epilepsy—particularly when the infant is born postterm rather than preterm—varying with the severity of toxemia, from an incidence rate ratio of 1.16 to 5 times expected (Wu et al., 2008).

Adab N., et al. The longer term outcome of children born to mothers with epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1575-1583.

Adeney K.L., Williams M.A., Miller R.S., et al. Risk of preeclampsia in relation to maternal history of migraine headaches. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;18:167-172.

Amato M.P., Portaccio E., Ghezzi A., et al. Pregnancy and fetal outcomes after interferon-ß exposure in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;75:1794-1802.

American College of Radiology Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. Manual on Contrast Media, sixth ed. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2004. pp. 61-66

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Obstetric Practice. Guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 2. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:647-651.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Obstetric Practice. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Number 33, January 2002. J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;77:67-75.

Airas L., et al. Breast-feeding, postpartum and prepregnancy disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;75:474-476.

Askie L.M., et al. on behalf of the PARIS collaborative group: antiplatelet agents for prevention of pre-eclampsia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2007;369:1791-1798.

Bates S.M., Greer I.A., Hirsh J., et al. Use of antithrombotic agents during pregnancy: the seventh ACCP conference on antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy. Chest. 2004;126:627S-644S.

Bermas B.L. Oral contraceptives in systemic lupus erythematosus—a tough pill to swallow? N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2602-2604.

Birnbaum J., Hellman D.B. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:704-709.

Borthen I., Eide M.G., Daltveit A.K., et al. Obstetric outcome in women with epilepsy: a hospital-based, retrospective study. BJOG. 2011;118:956-965.

Boskovic R., Wide R., Wolpin J., et al. The reproductive effects of beta interferon therapy in pregnancy: a longitudinal cohort. Neurology. 2005;65:807-811.

Bousser M.-G., Canard J., Kittner S., et al. Recommendations on the risk of ischaemic stroke associated with use of combined oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy in women with migraine. International Headache Society Task Force on Combined Oral Contraceptives & Hormone Replacement Therapy. Cephalalgia. 2000;20:155-156.

Brewer G.J., et al. Treatment of Wilson’s disease with zinc. VII: treatment during pregnancy. Hepatology. 2000;31:364-370.

Brodie M.J. Major congenital malformations and antiepileptic drugs: prospective observations—high dose lamotrigine may be teratogenic. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:145.

Brown D.W., Ducker N., Jamieson D.J., et al. Preeclampsia and risk of ischemic stroke among young women: results from the stroke prevention in young women study. Stroke. 2006;37:1055-1059.

Brown M.D., Levi A.D. Surgery for lumbar disc herniation during pregnancy. Spine. 2001;26:440-443.

Browning G.G. Bell’s Palsy: a review of three systematic reviews of steroid and anti-viral therapy. Clin Otolaryngol. 2010;35:56-58.

Brynhildsen J., Hansson A., Persson A., et al. Follow-up of patients with low back pain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:182-186.

California Medical Association Online. Document #1302, Pronouncement of Death: Diagnosis of death by neurologic criteria. Available at https://www.cmanet.org/member/downloadpdf2.cfm?oncallid=1302, 2009. Accessed 12/12/2009

Cantu-Brito C., Arauz A., Aburto Y., et al. Cerebrovascular complications during pregnancy and postpartum: clinical and prognosis observations in 240 hispanic women. Eur J Neurol. 2010;18:819-825.

Chambers C.D., Hernandez-Diaz S., Van Marter L.J., et al. Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:579-587.

Chan L.Y., Tsui M.H., Leung T.N. Guillain-Barre syndrome in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:319-325.

Chan W.S., Anand S., Ginsberg J.S. Anticoagulation of pregnant women with mechanical heart valves: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:191-196.

Chen H.-M., et al. Increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes for women with migraines: a nationwide population-based study. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:433-438.

Chen M.M., et al. Guidelines for computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:333-340.

Ciafaloni E., et al. Pregnancy and birth outcomes in women with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2006;67:1887-1889.

Cohen-Gadol A.A., et al. Neurosurgical management of intracranial lesions in the pregnant patient: a 36-year institutional experience and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:1150-1157.

Coppage K.H., Hinton A.C., Moldenhauer J., et al. Maternal and perinatal outcome in women with a history of stroke. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1331-1334.

Coyle P.K., Johnson K., Pardo L., et al. Pregnancy outcomes in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with glatiramer acetate (Copaxone). Neurology. 2003;60:A60.

Crawford P. Interactions between antiepileptic drugs and hormonal contraception. CNS Drugs. 2002;16:263-272.

Day J.W., Ricker K., Jacobsen J.F., et al. Myotonic dystrophy type 2: molecular, diagnostic and clinical spectrum. Neurology. 2003;60:657-664.

De Santis M. Gadolinium periconceptional exposure: pregnancy and neonatal outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol. 2007;86:99-101.

Diav-Citrin O., et al. Paroxetine and fluoxetine in pregnancy: a prospective, multicentre, controlled, observational study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66:695-705.

Dumont A., Flahault A., Beaufils M., et al. Effect of aspirin in pregnant women is dependent on increase in bleeding time. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:135-140.

EURAP Study Group. Seizure control and treatment in pregnancy. Observations from the EURAP epilepsy pregnancy registry. Neurology. 2006;66:354-360.

Fast A., Shapiro D., Ducommun EJ., et al. Low-back pain in pregnancy. Spine. 1987;12:368-371.

Feldman J.M. Cardiac arrest after succinylcholine administration in a pregnant patient recovered from Guillain-Barre syndrome. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:942-944.

Furie K.L., Kasner S.E., Adams RJ., et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:227-276.

Gaffield M.E., Culwell K.R., Lee C.R. The use of hormonal contraception among women taking anticonvulsant therapy. Contraception. 2011;83:16-29.

Gillman G.S., Schaitkin B.M., May M., et al. Bell’s palsy in pregnancy: a study of recovery outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:26-30.

Gladstone J.P., Dodick D.W., Evans R. The young woman with postpartum “thunderclap” headache. Headache. 2005;45:70-74.

Goadsby P.J., Goldberg J., Silberstein S.D. Migraine in pregnancy. BMJ. 2008;336:1502-1504.

Gulick E.E., Halper J. Influence of infant feeding method on postpartum relapse of mothers with MS. Int J MS Care. 2002;4:4-15.

Gutenberg A., et al. A radiologic score to distinguish autoimmune hypophysitis from nonsecreting pituitary adenoma preoperatively. Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1766-1772.

Haddad B., Sibai B.M. Expectant management of severe preeclampsia: proper candidates and pregnancy outcome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48:430-440.

Haas J., Hommes O.R. A dose comparison study of IVIG in postpartum relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:900-908.

Harden C.L., et al. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy—focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009;73:142-149.

Harden C.L., et al. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy–focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency: Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009;73:126-132.

Harden C.L., et al. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy–focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Available at http://www.aan.com/practice/guideline/uploads/339.ppt, 2009. Accessed 02/19/2010

Hernan M.A., Hohol M.J., Olek M.J., et al. Oral contraceptives and the incidence of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2000;55:848-854.

Hernandez-Diaz S., Werler M.M., Walker A.M., et al. Folic acid antagonists during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1608-1614.

Herzog A.G., Blum A.S., Farina E.L., et al. Valproate and lamotrigine level variation with menstrual cycle phase and oral contraceptive use. Neurology. 2009;72:911-914.

Hoff J.M., Daltveit A.K., Gilhus M.E. Myasthenia gravis: consequences for pregnancy, delivery, and the newborn. Neurology. 2003;61:1362-1366.

Hoff J.M., Gilhus M.E., Daltveit A.K. Pregnancies and deliveries in patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neurology. 2005;64:459-462.

Hoffman J.M., Daltveit A.K., Gilhus N.E. Myasthenia gravis in pregnancy and birth: identifying risk factors, optimizing care. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:38-43.

Holmes L.B., Harvey E.A., Coull B.A., et al. The teratogenicity of anticonvulsant drugs. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1132-1138.

Holmes L.B., Rosenberger P.B., Harvey E.A., et al. Intelligence and physical features of children of women with epilepsy. Teratology. 2000;61:196-202.