11 Neurological disorders

CEREBRAL PALSY (Spastic paralysis: spastic paresis; Little’s disease)

The term cerebral palsy embraces a number of clinical disorders, mostly arising in childhood, the feature common to all of which is that the primary lesion is in the brain. The incidence of these disorders is such that cerebral palsy constitutes a major social and educational problem.

Types. A number of clinical types may be recognised, of which the most important are:

SPASTIC PARESIS

Clinical features. Usually within the first year it is noticed that the child has difficulty in controlling the movements of the affected limbs, and there is delay in sitting up, standing and walking. Commonly the upper and lower limbs of one side are affected (hemiplegia). Less often there is involvement of a single limb (monoplegia), of both lower limbs (paraplegia), or of all four limbs (tetraplegia1). The trunk and face muscles may also be affected. On examination the features that are found constantly are weakness, spasticity, and imperfect voluntary control of movement. Usually there is also deformity, and in some cases there may be mental deficiency, impaired vision, or deafness. These various features are best considered separately.

Corrective splinting. Splints or plasters are especially useful in overcoming the deformities induced by spastic muscles. Deformity is first corrected by gradual stretching of the contracted muscles, if necessary under anaesthesia. The limb is held by plaster in the over-corrected position for 6–8 weeks. Thereafter removable braces or splints (orthoses) may be used indefinitely to prevent recurrence of the deformity.

SPINA BIFIDA

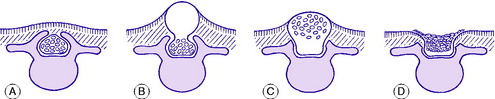

The term spina bifida implies a failure of the enfolding of the nerve elements within the spinal canal during early development of the embryo. The defect varies in degree and in its site (Fig. 11.1). In the mildest cases there is no more than a failure of fusion of one or more of the vertebral arches posteriorly, in the lumbo-sacral region. This is often of no clinical significance. Less often, the posterior bony deficiency is marked on the surface by an abnormality of the overlying skin, in the form of a dimple, a tuft of hair, a lipomatous mass, or a dermal sinus. In these cases there may be an underlying abnormality involving nerves of the cauda equina. These relatively minor varieties of spina bifida, in which the defect is not obvious at the skin surface, are termed spina bifida occulta. This contrasts with spina bifida aperta, in which there is a major defect of enfolding of the nerve elements, involving not only the bony vertebral arches but also the overlying soft tissues and skin, and often the meningeal membranes enclosing the spinal canal, so that the neutral tube itself is exposed and open. This major variant of spina bifida may occur anywhere in the spine but is commonest in the thoraco-lumbar region, and it is attended by grave impairment of nerve function.

SPINA BIFIDA OCCULTA (Occult spinal dysraphism)

As noted above, the bony defect is simply a failure of fusion of the vertebral arches posteriorly (Fig. 11.1A). When there is neurological involvement the overlying skin nearly always shows an abnormality, as already described.

In cases of occult spinal dysraphism there is no close correlation between the severity of the bony defect and the degree of neurological impairment. Often there is no neurological involvement; but on the other hand it may be severe. Clinically, the common manifestation of nerve involvement is muscle imbalance in the lower limbs, often with selective muscle wasting and deformity of the foot which often takes the form either of equino-varus or of cavus.

SPINA BIFIDA APERTA (Overt spinal dysraphism; variations include rachischisis, myelomeningocele and meningocele)

Pathology. The basic structural defect – failure of total closure of the embryonal neural tube or of mesodermal tissue to invest it – varies in degree. In the most serious defect, rachischisis, the neural tube is open and exposed on the surface (Fig. 11.1D). Cerebrospinal fluid leaks from the exposed upper end of the central spinal canal. In myelomeningocele the neural tube is closed by a membrane but the skin covering is deficient. The spinal cord and the nerve roots are displaced posteriorly into the sac and are outside the line of the vertebral canal (Fig. 11.1C). In meningocele the bulging sac consists of meninges and fluid only, the nerve elements being normally situated (Fig. 11.1B). The skin may or may not be intact.

The distinction between closed lesions, with intact skin, and open lesions in which skin is deficient and nerve tissue is exposed on the surface of the body, is fundamental because open lesions may demand operation within a few hours of birth to close the defect, if indeed active intervention is deemed advisable.

Visceral paralysis. Incontinence of bladder and bowel is present in a high proportion of patients.

Treatment. Every child with major neurological or visceral dysfunction from spina bifida should be admitted immediately to a special centre where a team of experienced specialists – including paediatrician, paediatric surgeon, neurosurgeon, and orthopaedic surgeon – may cooperate in deciding upon a programme that is best suited to the child. The team must first decide whether or not any surgical treatment, including closure of an open defect, is to be advised. This selective approach arose from review of large series where closure was universal: in the worst cases, with gross neurological deficit or hydrocephalus, the results were disastrous. In these it is probably better to adopt an expectant attitude, accepting the situation and relying simply on careful nursing and feeding. It has to be taken as inevitable that many of these badly affected infants will fail to survive.

POLIOMYELITIS (Anterior poliomyelitis; infantile paralysis)

Poliomyelitis is a virus infection of nerve cells in the anterior grey matter of the spinal cord, leading in many cases to temporary or permanent paralysis of the muscles that they activate. In many countries the incidence of the disease increased so much in the years succeeding the Second World War that its management – or rather the management of the paralytic disabilities that it produces – became one of the foremost problems of orthopaedic surgery. However, in the 1950s the incidence decreased very markedly in Western countries, in consequence of nationwide programmes of prophylactic vaccination; so much so that the disease has now been virtually eliminated. Nevertheless it is still encountered in certain countries of Asia and Africa.

Cause. It is caused by infection with a virus, of which at least three types have been identified.

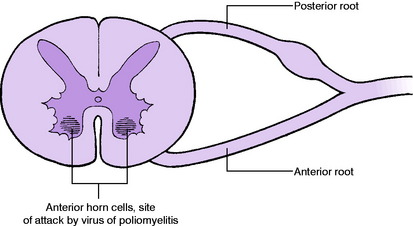

Pathology. After gaining access to the body through the nasopharynx or the gastro-intestinal tract, the virus finds its way to anterior horn cells of the spinal cord (Fig. 11.2) and sometimes to nerve cells in the brain stem. According to the virulence of the infection the cells may escape serious harm, or they may be damaged or killed. If cells are damaged there is paralysis of the corresponding muscles but recovery is possible; if the cells are killed paralysis is permanent. The extent and distribution of the lesions vary widely from case to case.

Stage of recovery. When any recovery of power occurs it may continue for about 2 years.1 The degree of recovery varies within the widest limits. There may be complete recovery or there may be none.

Prophylaxis. In Britain prophylactic vaccination is by an attenuated living virus, taken by mouth.

Stage of onset. The patient should rest in bed and may be given sedatives as required.

Appliances (orthoses). The purpose of external appliances or orthoses is to support joints that are no longer adequately controlled by muscles. They are required more often for the lower limbs and spine than for the upper limbs. The following are commonly prescribed:

Fig. 11.4 A Moulded polythene ankle foot orthosis (AFO) to control ankle instability. B Patient wearing ankle foot orthosis.

Operative treatment. Two main groups of operations are available:

PERIPHERAL NERVE LESIONS

Disorders of the peripheral nerves come largely within the sphere of the neurologist, but the orthopaedic surgeon is concerned with lesions that have a mechanical basis and with those that lend themselves to reconstructive surgery.

Clinical features. The effects of complete loss of conductivity of a nerve are motor, sensory, and autonomic. They are localised to the distribution of the nerve affected. Motor changes: The muscles are paralysed and wasted. Changes occur in the electrical reactions, but they take between two and three weeks to develop. These changes were described on page 27. Sensory changes: There is loss of cutaneous, deep, and postural sensibility. Autonomic changes: These include loss of sweating, loss of pilomotor response to cold (‘goose-skin’), and temporary vasodilation with increased warmth, which, however, is followed later by vasoconstriction and coldness.

When a nerve lesion has been caused by stretching, compression, or ischaemia the essential principle of treatment is to ensure that the harmful conditions are relieved, if necessary by operation to free the nerve or to remove a compressing agent.

1 Also termed (though less correctly because Latin is mixed with Greek) diplegia or quadriplegia.

1 It will be observed that the figure 2 appears in the stated duration of each of the first four stages – 2 weeks, 2 days, 2 months, 2 years. These are only very approximate figures, but they are easily memorised.