Chapter 8 Neurologic Presentation of Spinal Tumors

INTRODUCTION

One common feature of spinal tumors is their insidious course and the frequent delay between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis of the neoplasm. In many cases, the delay can be measured in months or even years. A major reason for the delay in diagnosis is the myriad of symptoms with which these patients present, and the overlap of these symptoms with common conditions such as degenerative spine disease. Adding to the challenge of diagnosis are a number of case reports in the literature describing spinal neoplasms with unusual clinical presentations, such as severe ear pain or subarachnoid hemorrhage.1,2 As would be expected, the most common presenting neurologic signs and symptoms of spinal tumors are dependent on their location. One way to classify the location is with respect to the dura and the spinal cord. Spinal tumors can be located in the intramedullary, intradural extramedullary, or extradural space.

EXTRADURAL TUMORS

CRANIOCERVICAL JUNCTION

Perhaps the most interesting and initially perplexing neurologic signs and symptoms of spinal neoplasms arise from tumors in the craniocervical junction. Initially, it may be very difficult to localize the tumor based on the symptoms. About 49–66% of patients will report neck and/or suboccipital pain as primary symptoms at the time of initial presentation.3,4 By the time the diagnosis is made, up to 75% will have suboccipital or neck pain, usually referable to the C2 dermatome. Dysesthesias are the second most common initial complaints, occurring in 39–54% of patients, and up to 95% of patients may complain of dysesthesias by the time of diagnosis.3 In decreasing order of frequency, the dysesthesias are found in the hands, arms, and lower extremities with up to 10.5% complaining of sensory disturbance in the face.3

Tumors compressing on the lower medulla and upper cervical spinal cord and thus affecting the descending trigeminal nucleus partly explain this finding. Cold dysesthesia of the lower limb has actually been described as a symptom pathognomonic for high cervical tumors.5,6 However, this is seen in fewer than 7% of patients. Weakness is the first symptom apparent to the patient in as few as 5.3%, but it is noted at some point by 40–46% in the upper extremities and 29–42% in the lower extremities. The sensory abnormalities and weakness lead to gait disturbance in roughly half of the patients by the time of diagnosis. Bladder dysfunction is present in about 22–33% by the time of diagnosis.

Even though up to 20% of patients may actually have a normal neurologic examination at the time of initial clinical presentation,4 most patients have at least some signs of a deficit. Tetraplegia or tetraparesis can actually be found in 15–25% of patients with a craniocervical region tumor. Others may present with a monoparesis/monoplegia of the upper extremity (13–17%), hemiparesis/hemiplegia (14–15%), or paraparesis/paraplegia of the upper extremities (13–20%). The pattern of motor deficit development is quite fascinating. An alternating, rotational pattern of weakness is known to be a hallmark of craniocervical junction tumors. Typically, the weakness will begin in one upper extremity. The patient then develops weakness in the ipsilateral lower extremity. If enough time passes, the weakness may then also involve the contralateral lower extremity, and finally the contralateral upper extremity. Of course there are patients who do not display this pattern, but its presence should certainly alert the physician to the possibility of a tumor in this region. The most likely explanation for this unique finding is the decussation of the medullary corticospinal tracts near the craniocervical junction.7 The upper extremity motor fibers are carried medially in the corticospinal tract before the decussation. Just past the decussation, the fibers destined for upper extremities are the most lateral, with the lower extremity fibers being medially located. Therefore, a slightly lateral tumor anterior to the spinal cord will have mass effect, first on axons to the ipsilateral upper extremity motor fibers, followed by the ipsilateral lower extremity, contralateral lower extremity, and finally the contralateral upper extremity.

Sensory findings also can be quite variable in these patients. Some loss of pain and temperature is found in 37–57%.3,4 Other sensory modalities affected include touch (22–30%), proprioception (27–38%), and hypalgesia of C2 (18–23%). A “cape distribution” of sensory loss can be found in 7–15%, and there is a dissociated sensory loss in 23–25%. As with motor findings, the sensory deficit is usually greater in the upper extremities compared with the lower extremities.

Other neurologic findings on examination are found in Table 8-1, which uses data from Yasuoka et al and Meyer et al.3,4

Table 8-1 Neurologic Findings with Extradural Tumors at the Craniocervical Junction*

| Neurologic Sign | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Atrophy | |

| Hands | 15–17 |

| Arms | 7–9 |

| Legs | 1–4 |

| Hyperreflexia | 71–83 |

| Babinski sign | 57–58 |

| Brown–Séquard | 23–29 |

| Gait disturbance | 40–47 |

| Nystagmus | 13–25 |

| Horner syndrome | 4–6 |

| Cranial nerve palsy | |

| V | 6 |

| VII | 1 |

| VIII | 1 |

| IX | 4–7 |

| X | 2–7 |

| XI | 28–32 |

| XII | 4–8 |

* Data from Yasuoka et al3 and Meyer et al.4

CERVICAL AND THORACIC

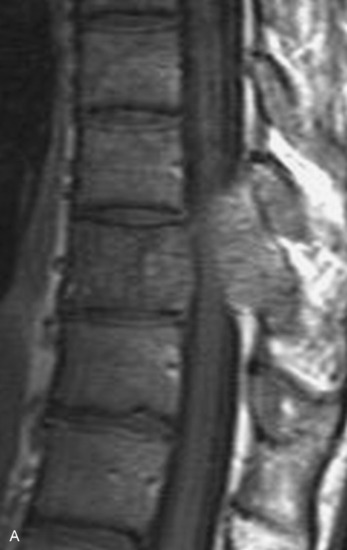

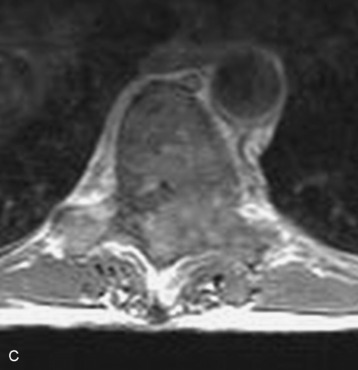

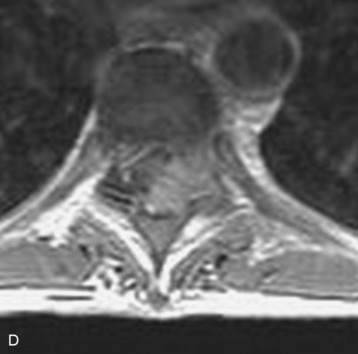

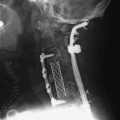

Spinal tumors in the cervical and thoracic regions may vary in their clinical presentation from absence of symptoms to complete spinal cord compression. Estimates of patients presenting with neurologic deficits range from 20–90%.8,9 Approximately 42% will have at least a serious neurologic deficit, such as paraplegia or complete loss of sphincter tone, by the time a diagnosis is made (Fig. 8-1).8 Metastatic lesions to the spine are the most common spinal tumors and are therefore reported on the most extensively in the literature. In retrospective studies of cancer patients, approximately 5–20% had evidence of spinal metastatic disease, yet fewer than 2% showed neurologic signs of spinal cord compression.10,11 As with craniocervical junction extradural tumors, pain is the most common initial symptom and has been reported as the presenting symptom in 61–96% of patients.8,9,12–14 Other symptoms at the time of diagnosis include weakness (69–76%), autonomic dysfunction (45–57%), sensory loss (51–55%), ataxia (3–5%), and even herpes zoster (2%).12,13,15 Actual findings on examination are tenderness (63%), weakness (77–97%), autonomic dysfunction (40–45%), sensory loss (66–90%), and ataxia (7%).13,16 The specific motor and sensory deficits depend on the location of the tumor within the cervical and thoracic spine (Fig. 8-2).

A careful history may alert the clinician to the fact that a tumor is the underlying cause of a patient’s symptoms. Pain caused by degenerative joint disease is relatively rare outside of the lumbar and cervical spine, and this type of pain is exacerbated with movement.17 Pain from spinal malignancy tends to be exacerbated by coughing, sneezing, and Valsalva maneuvers; persists with recumbency (especially noted at night); and is not improved with rest.12 Destruction of the joints also may produce dynamic instability and lead to pain with movement. Studies also have demonstrated that compressive metastatic lesions may cause compression of epidural venous plexuses, resulting in venous congestion and increased spinal cord edema.14,18,19 Extradural tumors may precipitate venous thrombosis, leading to subacute paraparesis.20

LUMBAR AND SACRAL

Sacral tumors, like tumors throughout the rest of the spine, most often present with pain as the most common initial symptom.21 Initially the pain is local, but as nerve roots become compressed, the pain radiates to the perineum, buttocks, external genitalia, and posterior thighs. With enough compression, sensory, motor, and even autonomic deficits arise.

FRACTURES

Pathologic fractures can occur anywhere along the spinal axis and are a common source of pain and neurologic deficits. Trauma may even cause a pathologic dislocation, leading to delayed paraplegia.22 In addition, a possible non-neurologic presentation is deformity, such as acute torticollis or kyphosis.23 In a review by Perrin and Livingston24 of pathologic fracture-dislocations, pain was the most prominent early symptom, occurring in 95% of patients. The pain was radicular in about 25% of patients, and eventually 80% demonstrated impaired motor function. A sensory level was documented in 60%, and Brown–Séquard’s syndrome developed in 20%. Unfortunately, by the time of surgery, 35% of patients were unable to ambulate and 15% were paralyzed.

INTRADURAL EXTRAMEDULLARY TUMORS

Tumors in this category are relatively common and include nerve sheath tumors, meningiomas, cauda equina ependymomas, and metastatic lesions. They present in a similar fashion to extradural tumors but with a higher incidence of neurologic signs. Again, pain is the most common initial symptom, and is exacerbated by recumbency.25,26 Approximately 70–90% of patients will have pain initially, with the pain being axial and/or radicular.27–29 Weakness and sensory changes also occur frequently, and more than 60% of patients who undergo surgical decompression or resection will have some degree of weakness. Motor deficits may sometimes manifest in the absence of pain.30 About 40% of patients have reflex changes, which can be hyporeflexia caused by root compression, or hyperreflexia from cord compression and myelopathy. Almost all patients will have some degree of sensory involvement, occasionally with a clear sensory level.27,28 Bowel and bladder dysfunction have been noted in 30–80% of patients with intradural tumors.

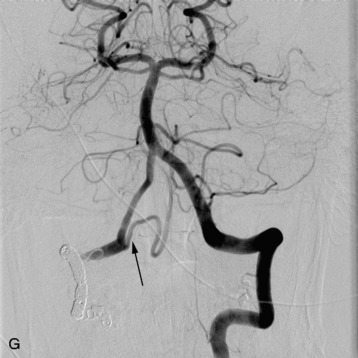

Intradural extramedullary tumors also have been reported to present with spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage.2,31 In these neoplastic spinal subarachnoid hemorrhages, the tumor resides in the region of the conus medullaris or cauda equina in about 80% of reported cases.32 When the hemorrhage occurs in the region of the cauda equina, the patient can acutely present with lower back pain, subacute development of lower extremity numbness (particularly in the posterior thigh and perineum), and weakness. The risk of such hemorrhage is greatest in patients receiving anticoagulation therapy. Of note, non-myxopapillary ependymomas are more likely to bleed than are myxopapillary ependymomas.32

INTRAMEDULLARY TUMORS

Tumors arising within the parenchyma of the spinal cord may present with a myriad of symptoms and signs that can be surprisingly similar to extramedullary tumors. Rare presentations, such as bulbomyelia and syringomyelia, may occur33 but, as in extramedullary tumors, pain is the most common initial symptom (30–85% of patients).34–37 The pain may be described as radicular, posterior midline, dull and aching, and/or paravertebral tightness/stiffness.37–41

Intramedullary tumors tend to present with a higher incidence of neurologic symptoms and signs. It is generally thought that intramedullary tumors cause symptoms via direct compression, rather than infiltration into the spinal parenchyma. Motor deficits were reported in 30–64% of patients, sensory deficits in 26–43%, and bowel and/or bladder dysfunction in 2–9%.35,37,38,42 Interestingly, in a group of patients with spinal ependymomas, two-thirds of patients with sensory disturbances reported that their symptoms started distally and progressed proximally.35

With objective neurologic examination at the time of clinical presentation, neurologic deficits are common in patients with intramedullary tumors. Overall, more than 92% of patients will have some degree of a motor deficit,37,38 and in one study37 42% of patients were nonambulatory. The neurologic deficit may be motor, sensory, or autonomic, and usually involves function of caudal to spinal segments at the level of the tumor. If a tumor is located in the cervical spine, the sensory and motor deficits may be confined to one upper extremity or one side of the body or may involve varying degrees of all four limbs. Below the level of the cervical cord, the weakness will only involve one or both of the lower extremities. Muscle atrophy is noted in about 5% of patients but increases in frequency in up to about 45% of patients with cervical tumors. Sensory deficits are seen in 62–87% of patients,37,38 with a clear sensory level noted in up to half of the patients. Bowel and/or bladder dysfunction was objectively noted in about 70% of patients.38 The constellation of motor and sensory findings is indicative of a true Brown–Séquard’s syndrome in 6–22%.37,38,43 Other findings on neurologic examination indicative of myelopathy include upgoing toes, hyperreflexia, and a Hoffman’s sign (for cervical lesions). About 4% of patients will have evidence of Horner’s syndrome, which is caused by involvement of the tumor in the descending sympathetic tracts within the cervical spinal cord.

4 Meyer FB, Ebersold MJ, Reese DF. Benign tumors of the foramen magnum. J Neurosurg. 1984;1:136-142.

8 Schaberg J, Gainer BJ. A profile of metastatic carcinoma of the spine. Spine. 1985;10:19-20.

17 Byrne NT. Spinal cord compression from epidural metastases. New Engl J Med. 1992;327:614-619.

18 Taylor AR, Byrnes DP. Foramen magnum and high cervical cord compression. Brain. 1974;97:473-480.

21 Payer M. Neurological manifestation of sacral tumors. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:1-6.