Chapter 63 Neurologic Emergencies and Stabilization

Neurocritical Care Principles

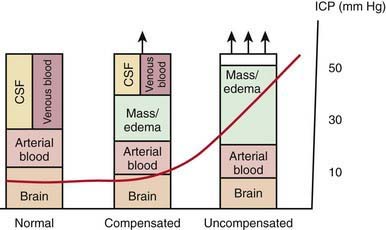

Increases in intracranial volume can result from swelling, masses, or increases in blood and CSF volumes. As these volumes increase, compensatory mechanisms decrease ICP by (1) decreasing CSF volume (CSF is displaced into the spinal canal or absorbed by arachnoid villi), (2) decreasing cerebral blood volume (venous blood return to the thorax is augmented), and/or (3) increasing cranial volume (sutures pathologically expand or bone is remodeled). Once compensatory mechanisms are exhausted (the increase in cranial volume is too large), small increases in volume lead to large increases in ICP or intracranial hypertension (Fig. 63-1). As ICP continues to increase, brain ischemia can occur as CPP falls. Further increases in ICP can ultimately displace the brain downward into the foramen magnum—a process called cerebral herniation, which can become irreversible in minutes and may lead to severe disability or death.

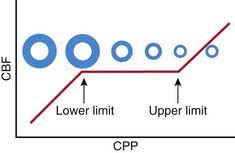

Oxygen and glucose are required by brain cells for normal functioning, and these nutrients must be constantly supplied by cerebral blood flow (CBF). Normally, CBF is constant over a wide range of blood pressures (blood pressure autoregulation of CBF) via actions mainly within the cerebral arterioles. Cerebral arterioles are maximally dilated at lower blood pressures and maximally constricted at higher pressures so that CBF does not vary during normal fluctuations (Fig. 63-2). Acid-base balance of the CSF (often reflected by acute changes in PaCO2), body/brain temperature, glucose utilization, and other vasoactive mediators (i.e., adenosine, nitric oxide) can also affect the cerebral vasculature.

Attention to detail and constant reassessment are paramount in managing children with critical neurologic insults. Among the most valuable tools for serial, objective assessments of neurologic condition is the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (see Table 62-3). Originally developed to assess level of consciousness after traumatic brain injury (TBI) in adults, the GCS is also valuable in pediatrics. Modifications to the GCS have been made for nonverbal children and are available for infants and toddlers (see Table 62-3). Serial assessments of the GCS score along with a focused neurologic examination are invaluable to detection of injuries before permanent damage occurs in the vulnerable brain.

Traumatic Brain Injury

Laboratory Findings

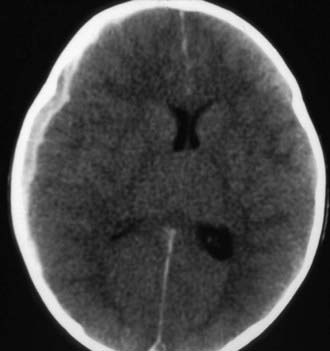

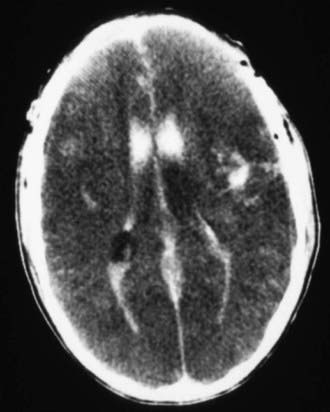

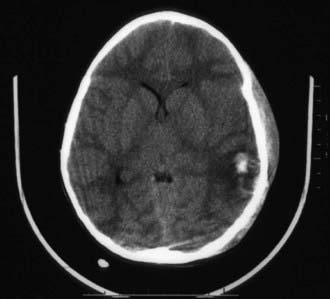

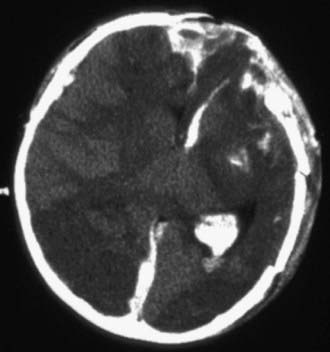

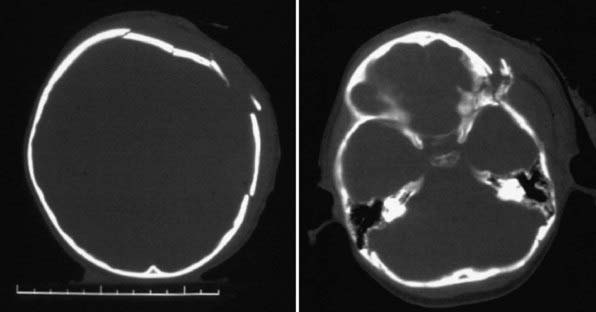

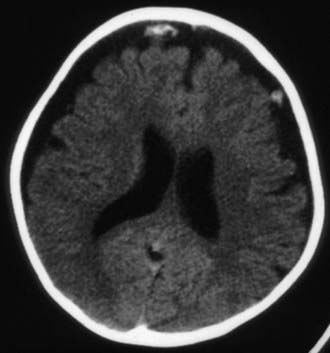

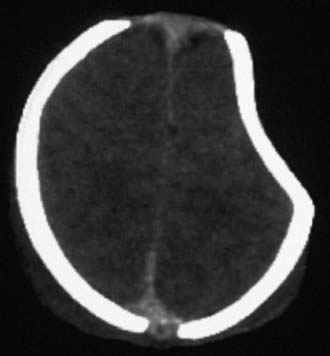

Cranial CT should be obtained immediately after stabilization (Figs. 63-3 to 63-11). Generally, other laboratory findings are normal in isolated TBI, although occasionally coagulopathy or the development of the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) or, rarely, cerebral salt wasting is seen. In the setting of TBI with polytrauma, other injuries can result in laboratory abnormalities, and a full trauma survey is important in all patients with severe TBI (Chapter 66).

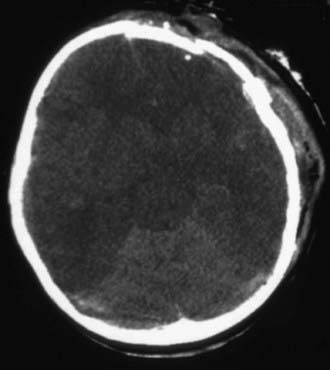

Figure 63-3 Abusive head trauma in an infant. Note the subdural fluid collections, dilated ventricles, and blood.

Figure 63-7 A depressed skull fracture due to traumatic delivery with forceps. Brain swelling can be seen.

Treatment

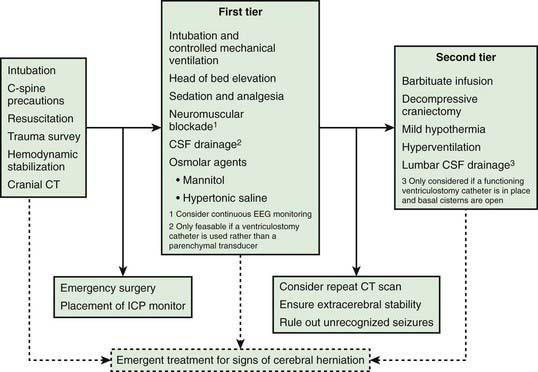

Infants and children with severe or moderate TBI (GCS score 3-8 or 9-12, respectively) receive intensive care unit (ICU) monitoring. Evidence-based guidelines for management of severe TBI have been published (Fig. 63-12). This approach to ICP-directed therapy is also reasonable for other conditions in which ICP is monitored. Care involves a multidisciplinary team comprising pediatric caregivers from neurologic surgery, critical care medicine, surgery, and rehabilitation, and is directed at preventing secondary insults and managing raised ICP. Initial stabilization of infants and children with severe TBI includes rapid sequence tracheal intubation with spine precautions along with maintenance of normal extracerebral hemodynamics, including blood gas values (PaO2, PaCO2), MAP, and temperature. Intravenous fluid boluses may be required to treat hypotension. Euvolemia is the target, and hypotonic fluids should be rigorously avoided; normal saline is the fluid of choice. Pressors may be needed as guided by monitoring of central venous pressure (CVP), with avoidance of both fluid overload and exacerbation of brain edema. A trauma survey should be performed. Once stabilized, the patient should be taken for CT scanning to rule out the need for emergency neurosurgical intervention. If surgery is not required, an ICP monitor should be inserted to guide the treatment of intracranial hypertension.

Abusive Head Trauma

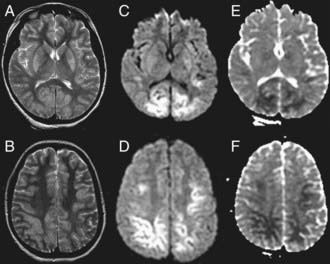

Abusive head trauma is the most common cause of death from TBI in infants (Chapter 37) (see Figs. 63-3 to 63-6). Most cases occur in the initial 2 years of life. Affected infants can be initially misdiagnosed; severe inflicted TBI can be complicated by repeated injury and/or extracerebral injuries. Delayed deterioration despite normal initial GCS score can be seen. MRI findings and serum biomarker test results indicate that these patients often exhibit more evidence of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury than is seen in non-inflicted TBI. This may result from delay in presentation, seizures, apnea, or other factors; the history is often conflicting, and time of injury may be unclear. The patients are often managed with an approach similar to that outlined previously for non-inflicted TBI, including ICP-directed therapy. Severe TBI secondary to abuse often has a poor prognosis.

Global Hypoxic-Ischemic Insults and Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy

Epidemiology

Cardiac arrest is seen in about 8-20/100,000 children in the USA (Chapter 62). The incidence of perinatal HIE is between 1and 6/1,000 live full-term births.

Pathology

Global hypoxic-ischemic insults damage selectively vulnerable brain regions such as the hippocampus, Purkinje neurons in the cerebellum, the basal ganglia, and brainstem. Longer durations of arrest produce infarcts in watershed areas and ultimately brain death. In term newborns, hypoxic-ischemic insults can damage periventricular white matter tracks—albeit much less than in preterm babies (Chapter 93).

Laboratory Findings

In the ICU, blood gas, lactate, or electrolyte abnormalities may be seen and should be serially followed. Evidence of multiorgan injury or failure, including markers of myocardial, renal, and hepatic injury/function, can be seen and should be serially evaluated. Acute echocardiographic assessment and cranial CT should be strongly considered. EEG can identify encephalopathy, seizures, and subclinical electrical status epilepticus, particularly in the child with post-resuscitation coma. If neuromuscular blockade is required, continuous EEG should be considered. MRI is useful in the subacute period to define the extent of brain injury (Fig. 63-13).

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The history is often clear with regard to the etiology of the hypoxic-ischemic insult, but if it is not, the cause of the arrest should be determined. In children, poisoning, hyperkalemia, unrecognized trauma, child abuse, myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, and prolonged QT syndrome should be considered (Chapter 430). Pertinent obstetric history should be sought in a newborn with perinatal asphyxia. HIE in children may also be secondary to other conditions, such as septic shock.

Treatment

Acute resuscitation from cardiac arrest is addressed in Chapter 62. Neurointensive care focuses on the post-resuscitation phase in the PICU. The first goal is to optimize cardiac output and cerebral perfusion. Mechanical ventilation should target normalization of PaO2 and PaCO2—avoiding inadvertent hyperoxia or hypocarbia. Systemic hemodynamics should be optimized by normalizing MAP for age; systemic perfusion and capillary refill; central venous oxygen saturation (>65%); and pH. Volume expansion with isotonic fluids should be performed to treat shock and should be further guided by urine output (>1.0 mL/kg/hr) and CVP. Inotropes, pressors, and/or vasodilators may be required to prevent re-arrest and to optimize cerebral and systemic perfusion. Hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia should be prevented or, if present, treated. Arrhythmias should be treated. If conventional hemodynamic support is inadequate, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) should be considered.

Status Epilepticus

Etiology

Status epilepticus is defined as a seizure of sufficient duration to provide an enduring epileptic focus. In more practical terms, persistent, disorganized, involuntary brain activity lasting for more than a proscribed amount of time (varying from 1 min to 30 min; usually 15-30 min) is characteristic of status epilepticus. The causes are myriad; epilepsy, abrupt discontinuation of anticonvulsive medications, febrile seizures, TBI, and encephalitis and other central nervous system infections are the leading causes in children (Chapter 586.8).

Stroke and Intracerebral Hemmorrhage

Etiology

The predominant causes of ischemic stroke in children are sickle cell disease and heart disease (either acquired or congenital), which are responsible for ≈50% of strokes after the neonatal period (Chapter 594). A variety of other conditions, including carotid or vertebral arterial dissection, infectious (meningitis, sinusitis), hematologic (prothrombotic states, polycythemia, chronic anemias), traumatic, and autoimmune (systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel) disorders, and vasculitis, are risk factors. Intracerebral hemorrhage results from abnormal vascular development and subsequent rupture of cerebral vessels, with arteriovenous malformations, hemangiomas, or aneurysms. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is often caused by severe dehydration and hypercoagulable states.

Adelson PD, Bratton SL, Carney NA, et al. Guidelines for the acute medical management of severe traumatic brain injury in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2003;4:S1-S75.

Atabaki SM, Stiell IG, Bazarian JJ, et al. A clinical decision rule for cranial computed tomography in minor pediatric head trauma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:439-445.

Bernard S. Hypothermia after cardiac arrest: expanding the therapeutic scope. Crit Care Med. 2009:S227-S233.

Bishop NB. Traumatic brain injury: a primer for primary care physicians. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2006;36:313-340.

Bulger EM, May S, Brasel KJ, et al. Out-of-hospital hypertonic resuscitation following severe traumatic brain injury. JAMA. 2010;304(13):1455-1464.

Chambers IR, Stobbart L, Jones PA, et al. Age-related differences in intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure in the first 6 hours of monitoring after children’s head injury: association with outcome. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:195-199.

Deverber G, Kirkham F. Guidelines for the treatment and prevention of stroke in children. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:983-985.

Dunning J, Daly JP, Lomas JP, et al. Children’s head injury algorithm for the prediction of important clinical events study group: Derivation of the children’s head injury algorithm for the prediction of important clinical events decision rule for head injury in children. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:885-891.

Hammell CL, Henning JD. Prehospital management of severe traumatic brain injury. BMJ. 2009;338:1262-1266.

Hutchinson JS, Ward RE, Lacroix J, et al. Hypothermia therapy after traumatic brain injury in children. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2447-2456.

Klein GW, Hojsak JM, Schmeidler J, Rapaport R. Hyperglycemia and outcome in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2008;153:379-384.

MRC CRASH Trial CollaboratorsPerel P, Arango M, Clayton T, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: practical prognostic models based on large cohort of international patients. BMJ. 2009;336:425-429.

Mullen MT, McKinney JS, Kasner SE. Blood pressure management in acute stroke. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:559-569.

Polderman KH. Induced hypothermia and fever control for prevention and treatment of neurological injuries. Lancet. 2009;371:1955-1969.

Riviello JJJr, Ashwal S, Hirtz D, et al. Practice parameter: diagnostic assessment of the child with status epilepticus (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2006;67:1542-1550.

Roach ES, Golomb MR, Adams R, et al. Management of stroke in infants and children: a scientific statement from a special writing group of the American Heart Association Stroke Council and the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Stroke. 2008;39:2644-2691.

SAFE Study Investigators, Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group, Australian Red Cross Blood Service; George Institute for International HealthMyburgh J, Cooper DJ, Finfer S, et al. Saline or albumin for fluid resuscitation in patients with traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:874-884.

Sagalyn E, Band RA, Gaieski DF, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest in clinical practice: review and compilation of recent experiences. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:S223-S226.

Shankaran S. Neonatal encephalopathy: treatment with hypothermia. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:437-443.

Smits M, Dippel DWJ, Steyerberg EW, et al. Predicting intracranial traumatic finding on computed tomography in patients with minor head injury: the CHIP prediction rule. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:397-405.

Stein SC, Fabbri A, Servadei F, et al. A critical comparison of clinical decision instruments for computed tomographic scanning in mild closed traumatic brain injury in adolescents and adults. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:180-188.

Willmot C, Ponsford J. Efficacy of methylphenidate in the rehabilitation of attention following traumatic brain injury: a randomized, crossover, double blind, placebo controlled inpatient trial. J Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:552-557.

Yeates KO, Taylor HG, Rusin J, et al. Longitudinal trajectories of postconcussive symptoms in children with mild traumatic brain injuries and their relationship to acute clinical status. Pediatrics. 2009;123:735-743.

Young GB. Neurologic prognosis after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:605-611.

63.1 Brain Death

Clinical Manifestations

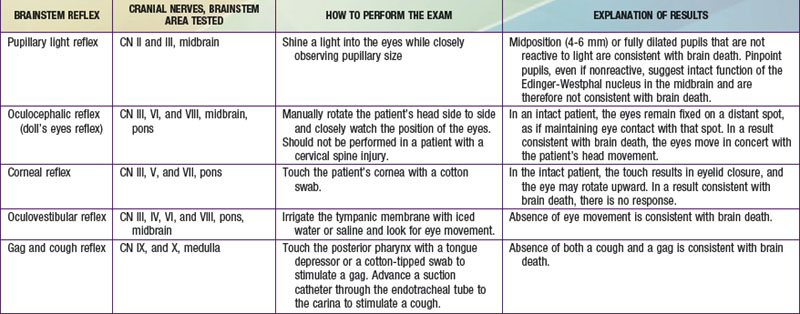

Brainstem reflexes must be absent. A listing of the brainstem reflexes to be tested, the brainstem location of each reflex, and the result of each test that is consistent with a diagnosis of brain death can be found in Table 63-1.

Documentation

Ashwal S, Serna-Fonseca T. Brain death in infants and children. Crit Care Nurse. 2006;26:117-128.

Greer DM, Varelas PN, Haque S, et al. Variability of brain death determination guidelines in leading US neurologic institutions. Neurology. 2008;70:284-289.

Mathur M, Petersen L, Stadtler M, et al. Variability in pediatric brain death determination and documentation in Southern California. Pediatrics. 2008;121:988-993.

Miller FG, Truog RD. The incoherence of determining death by neurologic criteria: a commentary on Controversies in the Determination of Death, a white paper by the President’s Council on Bioethics. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2009;19:185-193.

Morenski JD, Oro JJ, Tobias JD, et al. Determination of death by neurologic criteria. J Intensive Care Med. 2003;18:211-221.

1995 Practice parameters for determining brain death in adults (summary statement): the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 1995;45:1012-1014.

1987 Report of Special Task Force. Guidelines for the determination of brain death in children, American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Brain Death in Children. Pediatrics. 1987;80:298-300.

Saposnik G, Basile VS, Young GB. Movements in brain death: a systematic review. Can J Neurol Sci. 2009;36:154-160.

Shemie SD, Pollack MM, Morioka M, et al. Diagnosis of brain death in children. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:87-92.