Neurogenetics

Introduction

identification of gene products, enhancing understanding of pathophysiology and potentially allowing the development of treatments

identification of gene products, enhancing understanding of pathophysiology and potentially allowing the development of treatmentsClues to diagnosis

Selected inherited diseases

Single gene abnormalities

Autosomal dominant disorders

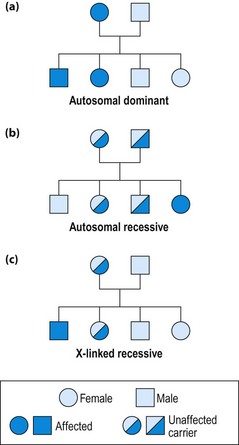

Males or females are equally affected, transmission is from mother or father and 50% of offspring are affected (Table 1; Fig. 1a).

| Condition | Clinical features | Genetic defect |

|---|---|---|

| Huntington’s disease | Progressive dementia with chorea | Huntington, chromosome 4 |

| Myotonic dystrophy | Progressive myotonia and weakness, with multisystem disease (p. 112) | Myotonin protein kinase, chromosome 19 |

| Torsion dystonia (some families) | Generalized dystonia (p. 92) | Chromosome 9 |

| Dopa-responsive dystonia (rare but treatable) | Generalized dystonia, very responsive to levodopa | Defects of tyrosine hydroxylase and coenzymes |

| Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type I | Progressive demyelinating neuropathy with pes cavus and champagne bottle legs |

Autosomal recessive disorders

Males and females are equally affected, often without a family history, as parents are asymptomatic carriers; 25% of offspring are affected (Fig. 1b). Autosomal recessive disorders are often due to single enzyme defects, raising the possibility of therapeutic metabolic manipulation (Table 2).

Table 2 Some rare but important treatable autosomal recessive disorders

| Condition | Clinical features | Genetic defect |

|---|---|---|

| Wilson’s disease | Movement disorders and psychiatric illness. Liver disease in children (p. 92) | Copper-binding ATPase |

| Phenylketonuria | Developmental delay, retardation, hypopigmentation, emotional disturbance. Treated by diet. Routine screening at birth | Phenylalanine hydroxylase |

| Galactosaemia | Failure to thrive, retardation, liver and renal disease, hypoglycaemia. Treatment is avoidance of all milk products | Galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase |

| Vitamin E deficiency | Progressive ataxia, with myelopathy, ophthalmoplegia and neuropathy. Treatment is with vitamin E supplements | Abetalipoproteinaemia |

X-linked recessive disorders

These diseases almost exclusively affect males; females are carriers (Fig. 1c). The disease may appear to skip generations. Each son of a carrier is at 50% risk and each daughter is at 50% risk of being a carrier. Daughters of affected males may be carriers, but sons can never be affected. In the female, every cell contains only one active X chromosome: which one is inactivated varies between cells. If the abnormal chromosome is active in some cells important in the disease process (e.g. muscle cells in Duchenne muscular dystrophy), the female may suffer some disease symptoms. Duchenne (DMD) and Becker (BMD) muscular dystrophies are both due to abnormalities of the same gene, encoding the protein ‘dystrophin’ (p. 112). In DMD the protein may be absent, whereas in BMD it is deficient. Clinical features of muscular dystrophy are summarized on page 112. Fragile X syndrome (30% of female carriers affected) is a common cause of mental retardation and may cause late-onset ataxia.

Common diseases

In some common conditions, relatives of sufferers are more frequently affected than the general population (Table 3). The increased risk is small and cannot be attributed to a simple gene defect. This may be because a combination of several genes and environmental factors are required for the disease, and having some of the abnormal genes puts the individual at increased risk. In other diseases, a minority of cases are inherited and these often have a younger onset than the sporadic, presumed polygenic forms. For example, familial Alzheimer’s disease is an autosomal dominant condition, with onset around 45–55 years, due to mutations of the presenilin or amyloid precursor protein genes.

| Condition | Risk in general population | Risk in first-degree relatives |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple sclerosis | 0.2% | 5–15% |

| Epilepsy | 0.5% | 5% (some types much higher) |

| Alzheimer’s disease | <1% at age 60 years (p. 54) | Three times age-matched controls |

| Parkinson’s disease | 0.5% over age 70 years | 1.5% (higher if younger onset) |

Ethical issues of the new genetics

Being able to establish that an individual carries a gene defect raises ethical problems. These are highlighted by Huntington’s disease (autosomal dominant), which causes late-onset chorea with dementia (p. 93) with complete penetrance. Finding the gene in clinically normal people means that they will develop the disease and that their children are at 50% risk. This knowledge places a considerable burden, especially for those who have seen the decline of relatives affected with this devastating illness. Adults may not want to know their genetic status, but if their teenage child wishes to be tested and find they carry the gene, they know that their parent must also develop the disease. It is, therefore, important that patients understand fully the implications of any test they undergo, both for themselves and their families. Counselling should be undertaken by specialized clinical geneticists, and ideally should involve the whole family.