Chapter 31 Nerve Entrapment Around the Elbow

Background/aetiology

The clinician should also be aware that occasionally a ‘double-crush’ phenomenon may occur. This was first described by Upton and McComas1 in 1973 who stated that ‘neural function was impaired because single axons, having been compressed in one region, become especially susceptible to damage at another site’. When this occurs in the upper limb the peripheral nerves become hypersensitized by proximal compression in the neck and are more susceptible to an otherwise well-tolerated level of compression.

The causes of compression can vary widely and are given below.

The anatomical structures around the elbow and, in particular, the various fibro-osseous tunnels and fibrous arches can cause rigid borders against which nerves may be compressed. The large range of elbow flexion will produce longitudinal traction on the nerves lying within the extensor compartment whilst compressive forces are applied to the nerves on the flexor surface. The ulnar nerve for example is subjected to longitudinal traction during terminal flexion. In addition it has been reported that 5.1 mm of ulnar nerve excursion is needed for elbow motion from 10° to 90°.2 This alone may compromise nerve function, but when combined with a second local insult such as a fibrous band or impinging osteophyte there is an increased likelihood of nerve irritation.

Congenital abnormalities can also produce nerve entrapment. The median and very occasionally the ulnar nerve may be compromised by the ligament of Struthers. This arises from a supracondylar spur on the medial border of the distal humeral shaft and extends obliquely to the medial epicondyle (Fig. 31.1).

Cubital tunnel syndrome (ulnar nerve)

Background and aetiology

The ulnar nerve at the level of the elbow is a large mixed motor and sensory nerve. It provides sensation to the ulnar one and a half digits of the hand, the volar and dorsal aspect of the hand and the medial aspect of the forearm. It is the motor supply to FCU, flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), palmaris brevis, adductor pollicis, the deep head of flexor pollicis brevis, seven interossei, three hypothenar muscles and the lumbricals to the little and ring fingers. With severe ulnar nerve compression at the elbow, the commonest site of muscle wasting, is the first dorsal interosseous muscle (Fig. 31.3).

The intraneural anatomy of the ulnar nerve at the elbow is organized into a layered formation of fibres.3 Sunderland showed that the sensory supply to the hand was present in the most superficial layer beneath which was found the innovation of the intrinsic muscles. The motor branches to the long flexor tendons were present in the deepest portion of the nerve. This patterning explains the early onset of sensory symptoms in the hand and why weakness of the long flexor tendons occurs at a much later stage with more significant compression.

The ulnar nerve blood supply is segmental and is a major concern during anterior transposition when the nerve is solely dependent on its intraneural supply. Prevel et al4 in a study on the extrinsic blood supply showed that the ulnar nerve receives two constant major pedicels from the superior ulnar collateral artery proximally and the posterior ulnar recurrent artery distally. In a cadaveric study they demonstrated by measuring total vessel length and distance to the medial epicondyle that the extrinsic vascular supply could be preserved during anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve, even after the nerve had been extensively mobilized. Simple decompression, however, has the advantage of leaving the nerve in situ with its surrounding vascular supply.

The ulnar nerve can be compressed at four main sites around the elbow:

Presentation, investigations and treatment options

Investigations

An ultrasound scan may be a useful test to visualize the ulnar nerve in cases of suspected subluxation in the larger obese patient. It will also reveal the lack of nerve excursion and movement on flexion and will show sites of tethering and compression. In addition it may indicate neural swelling proximal to the site of compression.5

Treatment options

Non-operative treatment

The non-surgical management of ulnar neuropathy should be restricted to mild to moderate entrapment.9 Simple analgesics and non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs may be useful for some patients. Others find splints beneficial although rigid devices are often poorly tolerated by both the patient and their bed-time partner. As a short-term measure we advise the patient to make a hole at the far end of a pillowcase. The hand can be passed through the pillowcase, alongside the pillow exiting on its far side through a small window that has been cut in the seam. During rest at night, flexion of the elbow, which often accompanies patients who sleep in the fetal position, is prevented. The elbow is unable to flex due to the bulky pillow. Patients often find this useful and more comfortable than other types of splint. In our experience, however, spontaneous resolution of symptoms is unlikely if the nerve entrapment syndrome is secondary to osteoarthritis, if there is a significant bony deformity such as cubitus valgus; or, if the compression appears to be severe, with significant motor wasting or sensory loss.

Surgical technique and rehabilitation

Simple decompression

Simple decompression is adequate for the vast majority of patients and can be performed through a relatively small incision that preserves the vascular bed of the nerve. The ulnar nerve is identified proximal to the elbow on the medial aspect of the arm. It can be felt as a rubbery cord. Having mobilized the skin edges, the nerve can be released for 10–15 cm proximal to the skin incision using appropriately angled retractors. Osborne’s fascia is then released between the two heads of the FCU (Fig. 31.5). In simple decompressions the medial intermuscular septum is not excised or released. Having completed the decompression the tourniquet is released, bleeding controlled and the wound closed with a subcuticular suture.

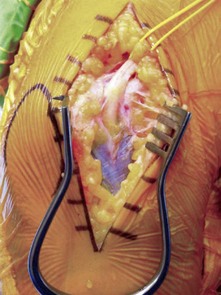

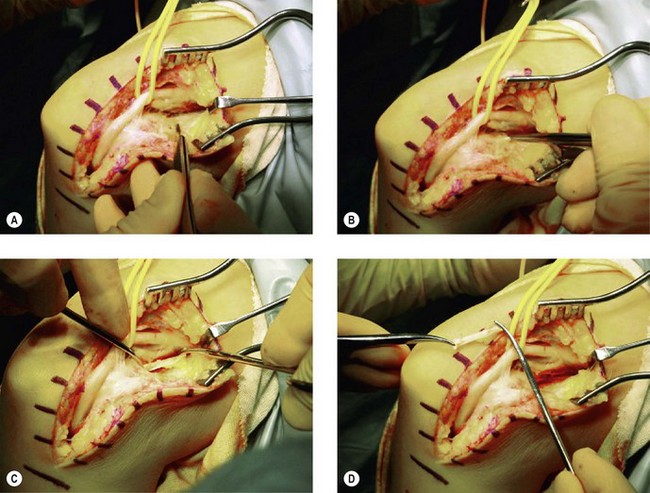

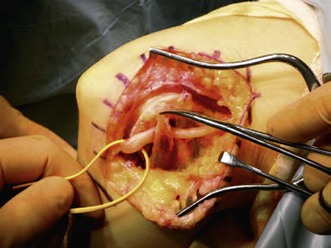

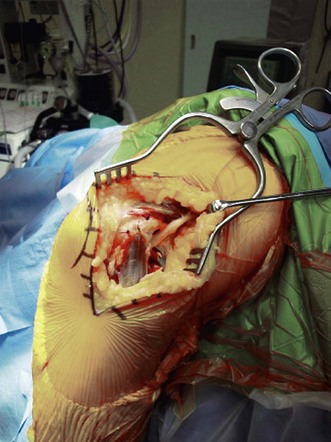

Subcutaneous anterior transposition

Having positioned the patient and undertaken the incision as previously described the ulnar nerve is identified as it passes beside the medial intermuscular septum. A 4 cm strip of the septum is then excised in order to allow the nerve to remain in the anterior compartment once it has been transposed. Distally the ulnar nerve is released for 5 cm as it passes down between the two heads of the FCU. The nerve can then be mobilized from its bed, preserving its longitudinal blood supply. The new bed for the ulnar nerve is then prepared. The fat is mobilized off the common flexor fascia for approximately 8–10 cm anterior to the medial epicondyle. A fascial strip is then elevated, as shown in Figure 31.6A. The nerve is transposed anteriorly and the fascial strip (Fig. 31.7) looped around the nerve and sutured back onto itself, securing the nerve in its anteriorly transposed position (Fig. 31.8). It is of vital importance that the ulnar nerve does not travel through any sharp angles, proximally, distally or underneath the fascial loop. In particular, the fascial loop should be loose and not cause any compression of the nerve. The transposed nerve should be tension free. The tourniquet is released, haemostasis achieved and the wound closed with a subcuticular suture.

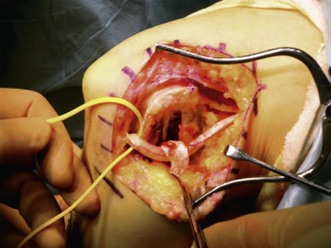

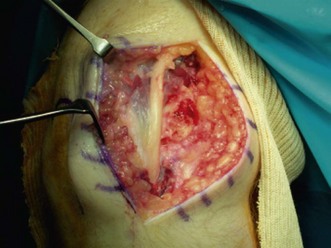

Submuscular anterior transposition

Submuscular transposition allows the anteriorly transposed nerve to be placed in a vascular bed deep to muscle.10 The nerve is exposed, as for a simple subcutaneous anterior transposition. The common flexor origin is reflected from the medial epicondyle, leaving a rim of tissue, to allow a meticulous repair following transposition. Having elevated the common flexor origin a space is created anterior to the medial epicondyle into which the nerve can be placed in a tension-free and smooth-running line (Fig. 31.9). The common flexor origin is then repositioned in its anatomical footprint and repaired to the remaining cuff of tissue. The wound is closed with a subcuticular absorbable suture. On the second postoperative day the patient’s dressings are reduced and early mobilization permitted to encourage neural gliding.

Partial medial epicondylectomy

The nerve is exposed as for a simple decompression, through a 5 cm incision. The common flexor origin is incised and elevated from the medial epicondyle. The medial epicondyle is then exposed subperiosteally and an osteotomy performed removing a small part of the epicondyle. Any sharp edges of bone are smoothed off with bone nibblers and the nerve anteriorly transposed. The common flexor origin is then reconstructed by suturing it to the surrounding periosteum (Fig. 31.10). It is important during this procedure that only a small part of the medial epicondyle is excised since excessive bone removal will violate the anterior bundle of the medial collateral ligament at the elbow causing significant valgus instability. O’Driscoll et al11 reported in a laboratory study, that only 19% of the width of the medial epicondyle should be removed in order to prevent damage to the underlying ligament. Having performed the epicondylectomy, haemostasis is achieved and the wound closed with a subcuticular suture. Early mobilization is encouraged, after 2 days.

Outcome including literature review

Dellon and Coert12 in a retrospective study of 121 consecutive patients (161 extremities) treated by submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve reported excellent results in 65%, good results in 23%, fair results in 4%, failure in 7.5% and recurrence of symptoms in 0.5%. The authors showed significant improvement in function in terms of both sensory and motor components of the ulnar nerve. Nouhan and Kleinert,13 using the same grading system as Dellon and Coert, presented the results of submuscular anterior transposition in 33 extremities with a mean duration of follow-up of 49 months. They reported good to excellent results in 97% (36%: excellent, 61%: good). Kaempffe and Farbach14 showed improvement in 93% of patients who had undergone medial epicondylectomy, which compares favourably with the results of other investigators.15–20

More recently a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials has been published comparing simple decompression of the ulnar nerve with anterior transposition. The study identified four randomized controlled trials, two of which had subcutaneous transpositions whilst the other two had submuscular transpositions. The results suggested that there was no difference in motor nerve conduction velocities or clinical outcome between simple decompression and subcutaneous or submuscular anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve.21

Complications of treatment

Anatomical variations can adversely affect the results of anterior submuscular transposition.22 These include a high origin of the superficial head of the pronator teres (20%), failure to divide a thick common flexor origin concealed within the flexor pronator mass and the presence of a periosteal origin of the FCU that is more medial than the origin of the common flexor mass and must be resected.22

Other complications of anterior submuscular transposition include neuroma formation (2%),23 reflex sympathetic dystrophy (2%)13 and loss of elbow extension. Care must also be taken with mobilization and repair of the common flexor mass as rupture has been reported in 4% of cases.12 The commonest complication following subtotal medial epicondylectomy is pain and tenderness at the osteotomy site. Kaempffe and Farbach14 reported medial epicondylar tenderness in 44% of their patients at 11 months’ follow-up.

Medial epicondylectomy may also result in medial elbow instability secondary to damage to the anterior band of the medial collateral ligament. This is usually due to over-generous excision of the epicondyle. Studies by Dinh and Gupta,15 however, have shown that if the procedure is performed properly instability does not occur. This has also been noted by Heithoff,16 who reported a 1% incidence of instability in a review of 350 cases. Amako et al17 and Froimson and colleagues18 on the other hand found a 74% incidence of instability in their patients, 20% of whom were symptomatic. Flexor/pronator weakness can also occur following the procedure. Heithoff and colleagues19 showed a 10% loss of grip strength with a 5% loss of pinch strength at a 2.3-year follow-up.

Reattachment of the flexor pronator mass and prolonged immobilization can result in elbow stiffness. Kaempffe and colleagues14 reported an average loss of 19° of extension in 15% of their patients. In a study of 160 cases, Seradge and Owen20 found that over a 10-year period the rate of recurrence was 13%. The recurrence rate in women was noted to be twice that of men (18% vs. 10%). This doubled in patients with ipsilateral carpal tunnel symptoms.

Personal view

Our management of cubital tunnel syndrome is to advise conservative treatment for patients with mild sensory symptoms of recent onset. This involves the use of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs together with night splintage. If when examined, the patient also has any evidence of early motor abnormality our preferred treatment option is in situ decompression. This we have found effective for the majority of patients with mild disease although we accept that it does not address tensile forces on the ulnar nerve generated by elbow flexion.24

For patients with more severe symptoms we prefer to perform an anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve making sure that there are no locally compressive forces on the nerve and that the nerve has a straight course at the end of the procedure. If the patient may require bony elbow surgery in the future (OK procedure, total elbow arthroplasty) we perform a subcutaneous transposition otherwise we undertake a submuscular transposition. We acknowledge that the study by Zlowodski et al24 would suggest that simple decompression of the nerve will give equally good results when compared to anterior transposition but we feel that in patients with severe symptoms it is helpful to relieve both the compressive and tensile forces on the nerve during elbow flexion.

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome and pronator syndrome

The anterior interosseous nerve branches from the median nerve immediately after the proximal margin of the flexor digitorum superficialis about 4 cm distal to the medial epicondyle of the humerus. It arises from the posterolateral aspect of the median nerve and is a pure motor nerve to FDP of the index and middle finger, FPL and pronator quadratus. The long flexor of the thumb and the FDP of the ring and middle fingers are supplied by multiple nerve branches along the medial and lateral edges of these muscles.25

A number of anatomical variations exist including the Martin Gruber anastomosis in the forearm, which may alter the clinical presentation of any associated syndrome. In addition variations have been described in relation to the passage of the anterior interosseous nerve through the pronator teres. Beaton and Anson26 showed that in 82% of cases the nerve passed between the deep and superficial heads of the pronator teres, deep to the ulnar head in 7% and through the superficial head in 2% of cases. In 9% of cases the deep head was absent.

Gantzer’s muscle (accessory head of the FPL) may also cause neurological compression. It lies under the deep head of the pronator teres and primarily arises from the medial epicondyle of the humerus (85%). al-Qattan27 found this muscle in over half of the 25 specimens he examined.

A supracondyloid process over the distal humerus may have attached the ligament of Struthers which can cause compression of the median nerve as it passes beneath it.28 Median nerve compression can either present as a motor palsy (anterior interosseous nerve syndrome) or with diffuse pain over the forearm and hand easily confused with carpal tunnel syndrome (pronator syndrome).

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome

Background and aetiology

Turner and Parsonage29 originally reported anterior interosseous nerve syndrome in relation to brachial neuritis. However it was Kiloh and Nevin30 who first described the specific features of the condition with isolated paralysis of the FPL and the median innervated FDP. The anterior interosseous nerve can be compressed at the following sites around the elbow:

Presentation, investigations and treatment options

Presentation

The commonest presentation is weakness of pinch with an inability to pick up objects or difficulty in writing. Often there is a history of forearm pain followed by weakness of the hand. A history of transient shoulder pain following a viral illness preceding the development of upper limb weakness usually points to brachial neuritis (Parsonage–Turner syndrome).29

Surgical technique and rehabilitation

The surgical indications for anterior interosseous nerve syndrome tend to be anecdotal, based mainly on retrospective case studies. Surgical intervention can improve symptoms although this may take between 4 weeks and 2 years.33,34

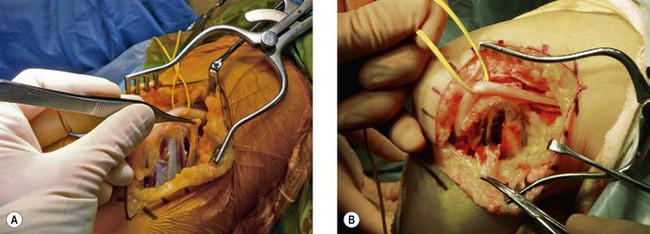

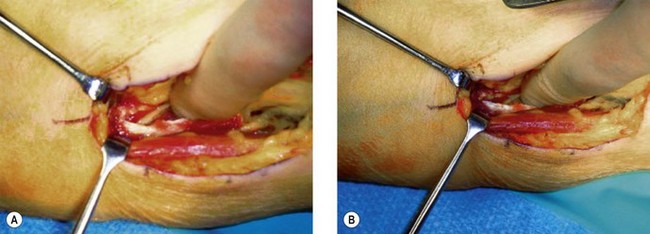

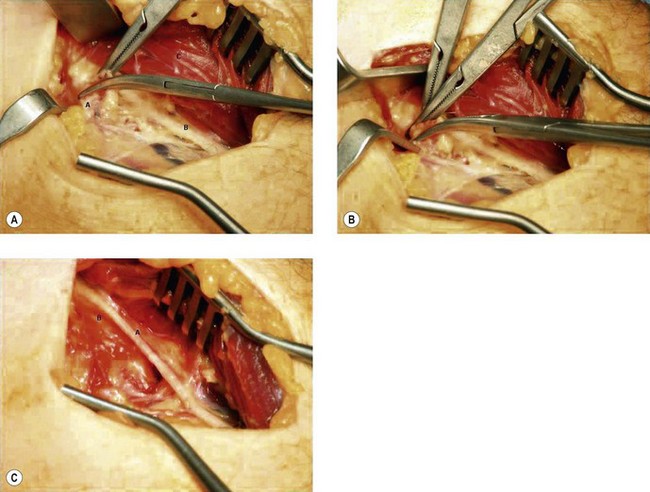

Under general anaesthesia with a high-arm tourniquet the patient is placed supine on the operating table with the affected arm on an arm board. A curved anterior incision is made approximately 10 cm in length centred on the anterior elbow crease. The deep fascia and lacertus fibrosis are identified and released. The median nerve is easily identified proximally, lying next to the brachial artery. If the ligament of Struthers is present it is excised, along with the supracondylar process. The anterior interosseous nerve is identified arising from the median nerve under the free edge of FCU (Fig. 31.11A). It is dissected free from beneath the muscle and fascia (Fig. 31.11B). The median nerve is now traced distally into the proximal forearm. In order to be certain that the nerve is not compressed in this region of the arm the bicipital aponeurosis may need to be incised longitudinally. The nerve then passes between the two heads of pronator teres. The humeral head of pronator teres occasionally requires mobilization and elevation. The FDS arch is then palpated and released, freeing the nerve. As with all nerve surgery, meticulous haemostasis is performed and the wound closed with a subcuticular absorbable suture.

Pronator syndrome

Presentation, investigations and treatment options

Presentation

Summary Box 31.2 Pronator syndrome provocation tests

| Site of compression | Provocation tests |

| Pronator teres | Symptoms reproduced by resisted forearm pronation with the elbow in flexion and with gradual extension of the forearm |

| Bicipital aponeurosis | Symptoms increased by resisted forearm flexion with the arm in supination |

| Fibrous arcade of flexor digitorum superficialis | Symptoms increased by resisted flexion of the proximal interphalangeal joints, forced forearm pronation or elbow flexion against resistance |

Radial tunnel syndrome

Michele and Krueger39 first described radial tunnel syndrome (RTS) as radial pronator syndrome in 1956, however Roles and Maudsley40 were the first to coin the term radial tunnel syndrome having defined the anatomical boundaries of the region and identified the structures that could cause compression of the posterior interosseous nerve.

Weitbrecht and Navickine41 noted an incidence of 1% in a large series of compression neuropathies of the upper limb. This relatively low figure may reflect the difficulty in making an accurate diagnosis with many cases being wrongly labelled as resistant tennis elbow.40,42

Cravens and Kline43 reported RTS secondary to repetitive activities associated with musicians swimmers and tennis players.

Background and aetiology

The radial nerve can be compressed at a number of levels as described by Konjengbam and Elangbam:44

Presentation, investigations and treatment options

Presentation

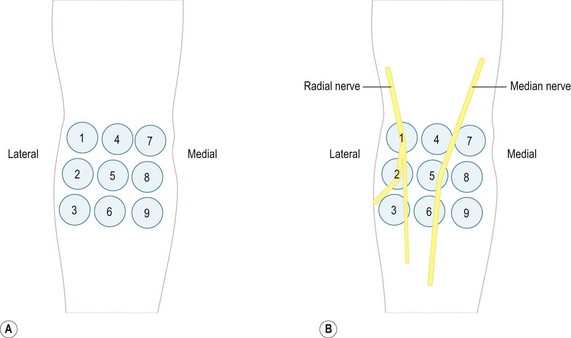

A useful examination technique is the rule of nine described by Loh et al.46 In Figure 31.12 the three medial pressure areas should not be painful and serve as controls. The proximal of the three middle circles misses the nerve and if painful usually indicates biceps tendonitis. The two more distally are in line with the median nerve and if painful may indicate a high median nerve lesion. The specific test for RTS is a pain response over the two lateral proximal circles.

Investigations

Electrophysiology is often unrewarding in radial tunnel syndrome. Albrecht et al47 have shown that the accuracy of diagnosis can only be improved to 50% even with detailed electromyograms. Differential injections38,42,48 may help distinguish lateral epicondylitis from RTS while imaging studies are only useful if a mass lesion around the elbow is suspected as the aetiological factor.

Surgical technique and rehabilitation

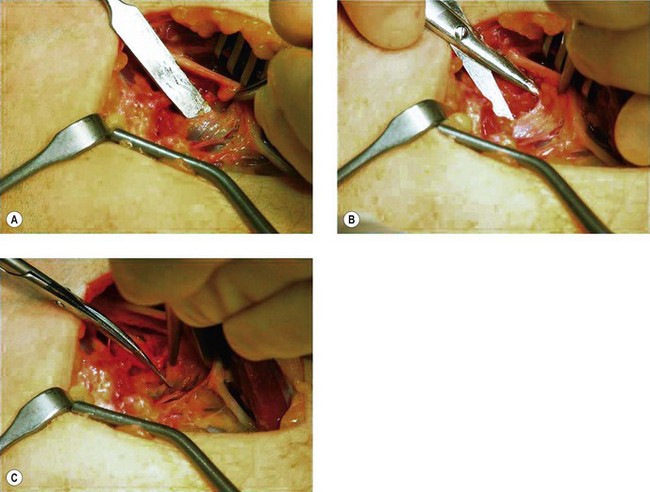

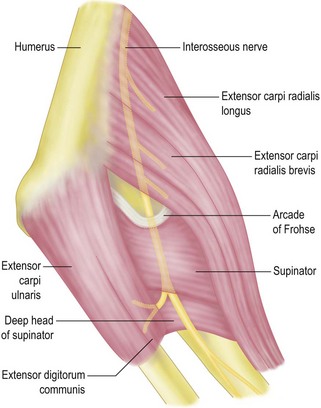

The incision begins approximately 5 cm proximal to the lateral epicondyle and is extended towards the lateral epicondyle before passing distally around the mobile wad. The plane between the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) and the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) is identified and developed allowing visualization of the superficial head of the supinator muscle (Fig. 31.13). In order to have adequate exposure it is often necessary to detach the ECRB tendon from the lateral epicondyle.

Figure 31.13 Plane of dissection between ECRB and ECU/EDC fibres.

(Courtesy of Professor J. Stanley.)

After ligating the vessels that constitute the leash of Henry (Fig. 31.14) the superficial radial nerve is identified and traced back to the posterior interosseous nerve which passes under the arcade of Frohse (Fig. 31.15) between the two heads of supinator.

At our institution we decompress the superficial head of the supinator completely. Occasional aponeurotic bands on the deep surface of the superficial head of the supinator can compress the nerve more distally and it is for this reason that we release the supinator throughout its whole length.42

Outcome including literature review

A systematic review of the literature by Huisstede et al49 found no randomized controlled trials or controlled clinical trials for testing the efficacy of different treatment protocols for RTS. The study indicated that surgical decompression of the radial tunnel might be effective in patients with RTS but the role of conservative management was less clear. Good to excellent relief of symptoms has been reported in 51–92% cases.50,51 The results from our institution52 show that 70% of patients have a favourable outcome following surgery although like Sotereanos53 we noted that patients who had claims pending did less well. Tsai et al38 suggest that the range of outcomes following surgery is likely to represent the subjective nature of the diagnosis with poor localization of pain, a more chronic presentation leading to permanent changes within the nerve or a more frequent association with compensation claims.

Posterior interosseous nerve palsy

Background and aetiology

Synovitis over the anterior radiocapitellar joint can cause local compression of the posterior interosseous nerve and result in paralysis and finger drop. In rheumatoid patients this can cause a diagnostic dilemma as it may be mistaken for rupture of the extensor tendons at the level of the wrist. The differential diagnosis of loss of digital extension is summarized in Summary box 31.3.

Summary Box 31.3 Differential diagnosis of loss of digital extension

| Pathology | Clinical features | Test |

|---|---|---|

| Posterior interosseous nerve palsy | Loss of digital and/or wrist extension | Tenodesis effect present |

| Extensor tendon rupture | Loss of digital extension | Loss of compensatory digital extension on passive flexion of the wrist (tenodesis effect) |

| Sagittal band rupture | Loss of digital extension | Passive extension of the finger allows centralization of the tendon over the metacarpophalangeal joint thus allowing the patient to maintain digital extension but not initiate it |

Presentation, investigations and treatment options

Presentation

Sensory symptoms are not a feature of posterior interosseous nerve palsy as the nerve only contains motor fibres. However, patients often present with deep-seated discomfort along the line of the radial nerve and into the extensor muscle mass. Occasionally a transient episode of forearm pain is followed by progressive weakness of the digital extensors as well as the extensor carpi ulnaris.38 In a pure posterior interosseous nerve palsy muscles of the mobile wad are spared due to their proximal innervation.

1 Upton AR, McComas AJ. The double crush in nerve entrapment syndromes. Lancet. 1973;2(7825):359-362.

2 Wright TW, Glowczewskie FJr, Cowin D, et al. Ulnar nerve excursion and strain at the elbow and wrist associated with upper extremity motion. J Hand Surg (Am). 2001;26(4):655-662.

3 Sunderland S. Nerves and Nerve Injuries, 2nd edn. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1978.

4 Prevel CD, Matloub HS, Ye Z, et al. The extrinsic blood supply of the ulnar nerve at the elbow: an anatomic study. J Hand Surg (Am). 1993;18(3):433-438.

5 Wiesler ER, Chloros GD, Cartwright MS, et al. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of ulnar neuropathy at the cubital tunnel. J Hand Surg (Am). 2006;31(7):1088-1093.

6 Osborne G. Compression neuritis of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Hand. 1970;2(1):10-13.

7 Apfelberg DB, Larson SJ. Dynamic anatomy of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;51(1):79-81.

8 Elhassan B, Steinmann SP. Entrapment neuropathy of the ulnar nerve. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(11):672-681.

9 Omer GSM. Management of nerve compression lesions in the upper extremity. In: Omer GSM, editor. Management of Peripheral Nerve Problems. Philadelphia PA: WB Saunders; 1980:569-605.

10 Learmonth J. 7A technique for transplanting the ulnar nerve. Surg Gynaecol Obstetr. 1942;75:92-93.

11 O’Driscoll SW, Jaloszynski R, Morrey BF, et al. Origin of the medial ulnar collateral ligament. J Hand Surg (Am). 1992;17(1):164-168.

12 Dellon AL, Coert JH. Results of the musculofascial lengthening technique for submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2003;85(7):1314-1320.

13 Nouhan R, Kleinert JM. Ulnar nerve decompression by transposing the nerve and Z-lengthening the flexor-pronator mass: clinical outcome. J Hand Surg (Am). 1997;22(1):127-131.

14 Kaempffe FA, Farbach J. A modified surgical procedure for cubital tunnel syndrome: partial medial epicondylectomy. J Hand Surg (Am). 1998;23(3):492-499.

15 Dinh PT, Gupta R. Subtotal medial epicondylectomy as a surgical option for treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2005;9(1):52-59.

16 Heithoff SJ. Cubital tunnel syndrome does not require transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg (Am). 1999;24(5):898-905.

17 Amako M, Nemoto K, Kawaguchi M, et al. Comparison between partial and minimal medial epicondylectomy combined with decompression for the treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg (Am). 2000;25(6):1043-1050.

18 Froimson AI, Anouchi YS, Seitz WHJr, et al. Ulnar nerve decompression with medial epicondylectomy for neuropathy at the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;265:200-206.

19 Heithoff SJ, Millender LH, Nalebuff EA, et al. Medial epicondylectomy for the treatment of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. J Hand Surg (Am). 1990;15(1):22-29.

20 Seradge H, Owen W. Cubital tunnel release with medial epicondylectomy factors influencing the outcome. J Hand Surg (Am). 1998;23(3):483-491.

21 Zlowodski M, Chan S, Bhandari M, et al. Anterior transposition compared with simple decompression for treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2007;89:2591-2598.

22 Williams EH, Dellon AL. Anterior submuscular transposition. Hand Clin. 2007;23(3):345-358. vi

23 Pasque CB, Rayan GM. Anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve for cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg (Br). 1995;20(4):447-453.

24 Catalano LW3rd, Barron OA. Anterior subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve. Hand Clin. 2007;23(3):339-344. vi

25 Spinner M. The anterior interosseous-nerve syndrome, with special attention to its variations. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1970;52(1):84-94.

26 Beaton LB, Anson BJ. The relation of the median nerve to the pronater teres muscle. Anat Rec. 1939;75:23-26.

27 al-Qattan MM. Gantzer’s muscle. An anatomical study of the accessory head of the flexor pollicis longus muscle. J Hand Surg (Br). 1996;21(2):269-270.

28 Barnard LB, Mccoy SM. The supracondyloid process of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1946;28(4):845-850.

29 Turner JW, Parsonage MJ. Neuralgic amyotrophy (paralytic brachial neuritis); with special reference to prognosis. Lancet. 1957;273(6988):209-212.

30 Kiloh LG, Nevin S. Isolated neuritis of the anterior interosseous nerve. Br Med J. 1952;1:859.

31 Schantz K, Riegels-Nielsen P. The anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J Hand Surg (Br). 1992;17(5):510-512.

32 Sood MK, Burke FD. Anterior interosseous nerve palsy. A review of 16 cases. J Hand Surg (Br). 1997;22(1):64-68.

33 Miller-Breslow A, Terrono A, Millender LH. Nonoperative treatment of anterior interosseous nerve paralysis. J Hand Surg (Am). 1990;15(3):493-496.

34 Goulding PJ, Schady W. Favourable outcome in non-traumatic anterior interosseous nerve lesions. J Neurol. 1993;240(2):83-86.

35 Johnson RK, Spinner M, Shrewsbury MM. Median nerve entrapment syndrome in the proximal forearm. J Hand Surg (Am). 1979;4(1):48-51.

36 Morris HH, Peters BH. Pronator syndrome: clinical and electrophysiological features in seven cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976;39(5):461-464.

37 Hartz CR, Linscheid RL, Gramse RR, et al. The pronator teres syndrome: compressive neuropathy of the median nerve. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1981;63(6):885-890.

38 Tsai P, Steinberg DR. Median and radial nerve compression about the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2008;90(2):420-428.

39 Michele AA, Krueger FJ. Lateral epicondylitis of the elbow treated by fasciotomy. Surgery. 1956;39(2):277-284.

40 Roles NC, Maudsley RH. Radial tunnel syndrome: resistant tennis elbow as a nerve entrapment. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1972;54(3):499-508.

41 Weitbrecht WU, Navickine E. Combined idiopathic forearm entrapment syndromes. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2004;142(6):691-696.

42 Stanley J. Radial tunnel syndrome: a surgeon’s perspective. J Hand Ther. 2006;19(2):180-184.

43 Cravens G, Kline DG. Posterior interosseous nerve palsies. Neurosurgery. 1990;27(3):397-402.

44 Konjengbam M, Elangbam J. Radial nerve in the radial tunnel: anatomic sites of entrapment neuropathy. Clin Anat. 2004;17(1):21-25.

45 Erak S, Day R, Wang A. The role of supinator in the pathogenesis of chronic lateral elbow pain: a biomechanical study. J Hand Surg (Br). 2004;29(5):461-464.

46 Loh YC, Lam WL, Stanley JK, et al. A new clinical test for radial tunnel syndrome – the Rule-of-Nine test: a cadaveric study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2004;12(1):83-86.

47 Albrecht S, Cordis R, Kleihues H, et al. Pathoanatomic findings in radiohumeral epicondylopathy. A combined anatomic and electromyographic study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1997;116(3):157-163.

48 Sarhadi NS, Korday SN, Bainbridge LC. Radial tunnel syndrome: diagnosis and management. J Hand Surg (Br). 1998;23(5):617-619.

49 Huisstede BM, Wijnhoven HA, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of complaints of the arm, neck, and/or shoulder (CANS) in the open population. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(3):253-259.

50 Jebson PJ, Engber WD. Radial tunnel syndrome: long-term results of surgical decompression. J Hand Surg (Am). 1997;22(5):889-896.

51 Ritts GD, Wood MB, Linscheid RL. Radial tunnel syndrome. A ten-year surgical experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;219:201-205.

52 Lawrence T, Mobbs P, Fortems Y, et al. Radial tunnel syndrome. A retrospective review of 30 decompressions of the radial nerve. J Hand Surg (Br). 1995;20(4):454-459.

53 Sotereanos DG, Varitimidis SE, Giannakopoulos PN, et al. Results of surgical treatment for radial tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg (Am). 1999;24(3):566-570.

54 Hashizume H, Nishida K, Nanba Y, et al. Non-traumatic paralysis of the posterior interosseous nerve. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1996;78(5):771-776.