ACUTE RENAL FAILURE

Acute renal failure is a comorbidity that can be encountered in the long case setting. It can also be incidentally encountered when an electrolyte profile with renal function indices is given to the candidate by an examiner during the discussion. In such situations it is important that the candidate correctly interpret the results and take charge of the discussion.

Case vignette

An 81-year-old man is admitted after an episode of syncope. On arrival in hospital his pulse rate is 30 bpm and blood pressure is 80/50 mmHg. He has a background history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, which has been managed with digoxin, and hypertension, managed with enalapril. He has been recently commenced on a non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug for painful arthritis of the knees. Investigations reveal his creatinine level to be 247 μmol/L and urea 26 mmol/L. His serum potassium level is 6.5 mmol/L. ECG reveals sinus bradycardia with tall tented T waves.

Approach to the patient

History

Ask about:

• the patient’s family history suggestive of any hereditary renal disease

• a past history of renal conditions

• whether the patient has taken any potentially renal-toxic drugs such as allopurinol, NSAIDs etc

• whether the patient has been recently commenced on or subjected to a dose increment of an agent such as a diuretic or an ACE inhibitor

• whether the patient has had recent vascular catheterisation procedures and/or radiocontrast exposure. Catheterisation can lead to cholesterol embolisation, which can cause acute renal damage. Radiocontrast material can be nephrotoxic.

• recent falls and prolonged immobilisation—these can lead to rhabdomyolysis, which in turn leads to acute renal failure due to myoglobin toxicity. It is important to rule this out in debilitated patients.

Remember: dehydration and hypovolaemia are the most common causes of acute renal failure, and assessment of the patient’s state of hydration is of primary importance in this setting.

In order of frequency, the most common causes of acute renal failure are:

Examination

1. Check the patient’s fluid status by examining the oral mucosa and checking skin turgur.

2. Check blood pressure and pulse.

3. Assess the JVP, look for peripheral oedema, and auscultate the lung fields for crepitations, looking for evidence of cardiac failure.

4. Look for rashes of vasculitis and evidence of connective tissue disease.

5. Examine the temperature chart for fevers, which would suggest sepsis.

6. Examine for wasting, hard mass lesions and lymphadenopathy, which would indicate malignancy.

7. Listen to the abdomen for a renal bruit, which may suggest renal artery stenosis.

8. In the anuric patient it is important to catheterise the bladder to exclude urethral obstruction and, if already catheterised, to flush the catheter to relieve any catheter obstruction.

9. Ask for the results of the urine analysis and the per rectum and per vagina examinations, looking for any pelvic mass lesions.

10. It is also important to request the results of microscopic examination of a fresh urine sample, looking for red cells, red cell casts and changes in the red cell morphology.

Causes of acute renal failure

• Impaired renal perfusion—shock, dehydration, severe left ventricular failure, renal artery obstruction

• Renal vein thrombosis

• Acute glomerular nephritis

• Acute vasculitis

• Acute tubular necrosis—ischaemic/toxic

• Exogenous renal toxins—drugs/ionic contrast agents

• Rhabdomyolysis

• Multiple myeloma

• Crystal-induced—e.g. urate, oxalate, pyrophosphate

• Haemolytic uraemic syndrome

• Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

• Outflow tract obstruction—ureteric, bladder-related or urethral

Common causes of acute renal failure according to anatomy of location

1. Prerenal causes—severe congestive cardiac failure, hypovolaemia, dehydration, bilateral renal artery stenosis

2. Intrinsic renal causes—acute glomerulonephritis, tubulointerstitial nephritis, drug toxicity, fat embolism, cholesterol emboli, hepatorenal syndrome, haemolytic-uraemic syndrome, acute tubular necrosis.

3. Postrenal causes—renal outflow tract obstruction due to calculi, blood clots, trauma and retroperitoneal fibrosis.

Remember: both kidneys need to be affected to cause acute renal failure, unless only one kidney, anatomically or functionally, is present.

Investigations

In addition to serum biochemistry, the following investigations would be helpful:

1. Full blood count—looking for anaemia (may suggest chronicity), leucocytosis (may suggest sepsis or inflammation) and thrombocytopenia (possibly lupus nephritis).

2. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate—if elevated, can suggest multiple myeloma, connective tissue disease or vasculitis.

3. Urine analysis and midstream urine—for microscopy, culture and sensitivities. The presence of red cell casts and dysmorphic red cells in the phase-contrast microscopy would suggest glomerulonephritis; hyaline casts are non-specific; white blood cell casts suggest tubulointerstitial disease.

4. Urinary electrolytes and creatinine—the following findings, if present, would suggest a prerenal cause for the renal failure:

6. Renal arterial Doppler study—looking for evidence of renal artery stenosis. The renal vascular resistive index should also be checked. This gives an assessment of the renal microvascular resistance and hence intrarenal vascular disease.

7. According to the clinical indication, the following tests can also be requested: serum electrophoresis, immunoelectrophoresis, antinuclear antibody test (ANA), extractable nuclear antibody tests (ENA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests (ANCAs), serum complement levels, streptococcal serology (antistreptolysin-O test (ASOT) and anti-DNAseB), hepatitis B serology and hepatitis C RNA assay, HIV serology and blood cultures if the patient is febrile.

8. If the kidney size is normal and the diagnosis is still uncertain, a renal biopsy is indicated.

Management

Fundamental steps in management are as follows:

1. Stop all non-essential renal-toxic drugs (e.g. NSAIDs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, gentamicin, amphotericin B, allopurinol) that would have potentially contributed to the current pathology. Decrease the dose of all renally excreted drugs.

2. Restore plasma volume and maintain a strict fluid balance, to avoid dehydration or volume overload. The daily fluid intake can be maintained at a volume equivalent to the previous day’s losses + 500 mL. Correct electrolyte imbalances, particularly hyperkalaemia. Monitor the patient’s body weight together with the fluid input and output on a daily basis.

3. Good nursing care is essential to prevent pressure sores and ensure hygiene.

4. Treat other acute medical conditions such as sepsis, vasculitis and thromboembolism.

5. Monitor renal function and electrolyte status regularly, to assess the need for renal replacement therapy.

CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE (CHRONIC RENAL FAILURE)

Case vignette

A 33-year-old woman presents with progressive lethargy, decreased appetite, insomnia, daytime somnolence and vomiting. She also complains of nocturia and amenorrhoea. She has been previously healthy and is not on any medication. Physical examination reveals conjunctival pallor, significantly elevated JVP, diffuse coarse pulmonary crepitations and peripheral oedema. Her blood pressure is 150/100 mmHg. Investigations reveal an Hb level of 8.7 g/dL, serum creatinine of 356 μmol/L and urea level of 31 mmol/L. Her serum potassium level is 5.1 mmol/L and serum albumin level 21 g/L.

1. How would you further work up this patient?

2. What are your differential diagnoses?

4. Describe how you would plan renal replacement therapy for this woman.

5. What measures would you take to prevent other complications of renal failure?

6. Describe in detail your comprehensive plan of management for this woman.

Approach to the patient

History

Ask about:

• the precise cause of the kidney disease—if known (see box)

• uraemic symptoms such as fatigue, anorexia, polyuria, nocturia, sleep disturbance, decreased appetite, nausea and vomiting

• symptoms such as pleuritic chest pain of pericarditis and uraemic pruritus

• neurological symptoms of peripheral neuropathy, restless legs, pain, asterixis and seizures. Some patients may complain of bone pain.

• how and when the initial diagnosis was made, and what initial steps were taken for the management of the renal failure

• different renal replacement therapy the patient has received and how the patient has coped with the same

• any acute events associated with cardiac rhythm disturbances (severe bradycardia and syncope due to hyperkalaemia) and acute pulmonary oedema

• dialysis:

– when the patient was commenced on dialysis

– the different modalities of dialysis (peritoneal and machine)

– complications of peritoneal dialysis, such as peritonitis etc

– surgery for vascular access for dialysis and the complications thereof. Some patients may have had recurrent surgical procedures for fistula construction.

– how the dialysis-dependent patient’s lifestyle has been affected by thedialysis.

Patients with renal failure are at a higher risk of cardiac disease and it is important to obtain details thereof. Ask about osteoporosis and fractures. Also ask about easy bruising.

Patients who have had renal transplantation would be able to provide important clinical information. Ask about the source of the grafted kidney, any previous graft rejection and how it was managed. Check how the patient is tolerating immunosuppression and chronic steroid therapy.

Obtain a detailed medication history, as patients with chronic renal failure are managed with multiple medications. Enquire into the patient’s diet and how they maintain fluid balance. Ask about menstrual disturbance in the younger female patient and erectile and sexual dysfunction in the male patient. Assess the patient’s psychological status and the social support available. Gain a good insight into the patient’s knowledge of this chronic disease condition.

Causes of chronic kidney disease

The causes of chronic kidney disease in our community in order of frequency are:

1. Diabetic nephropathy

2. Chronic glomerulonephritis

3. Artherosclerotic vascular disease (especially in the elderly)

4. Polycystic kidney disease

5. Reflux nephropathy

6. Hypertensive nephropathy,

7. Analgesic nephropathy

8. Chronic renal artery stenosis

9. Lupus nephritis

10. Vasculitides (particularly Wegener’s granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyarteritis)

11. Amyloidosis

12. Systemic sclerosis

13. Chronic urinary tract obstruction

14. Vasculopathy.

Examination

1. Look for a muddy brown complexion due to excess melanin deposition, and pallor due to anaemia. Confirm the pallor by looking at the mucosa. Examine the nails for brown discolouration. The patient may have generalised excoriations due to pruritus.

2. Perform a detailed cardiovascular examination, looking for evidence of fluid overload. Check the blood pressure and look for elevated JVP. Listen for cardiac murmurs (calcific stenosis of the aortic valve is not uncommon in this patient group) and pulmonary crepitations, and check for peripheral oedema.

3. Note abdominal scars of renal transplantation and palpate the transplanted kidney underneath.

4. If the patient is on haemodialysis, look for the form of vascular access. Note the vascular access device or the AV fistula (Fig 6.1). Check whether the fistula has a bruit. In patients on peritoneal dialysis, look for the Tenckhoff catheter (Fig 6.2) and for evidence of inflammation in the catheter site. These patients should be examined for any evidence of bacterial peritonitis (pus around the catheter entry point, tender or rigid abdomen, cloudy fluid in the bag).

Investigations

1. Renal function indices and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)—persistent eGFR of less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 is defined as chronic kidney disease.

2. Kidney imaging studies (ultrasound/CT/MRI) and kidney biopsy.

3. Urine analysis—for osmolality and protein levels (albuminuria/microalbuminuria).

4. Electrolyte profile—especially Na, K, Ca and P levels and acid/base status.

5. Full blood count—looking for anaemia.

6. If the patient is anaemic it is important to check the serum iron studies (serum iron, total iron binding capacity, serum ferritin and transferring saturation), vitamin B12 and folate levels and examine the blood film for red cell morphology.

7. Most of the investigations discussed under ‘acute renal failure’ are also indicated in chronic renal failure.

Management

Management objectives in kidney disease are:

Early identification of the need for renal replacement, and institution of the same, is another important aspect of the management plan.

1. Diet—renal diet is an important aspect of the management of the renal failure patient, and the objective of the special diet is to retard the progression of the renal failure and minimise the complications of renal failure while maintaining adequate nutrition. Restriction of protein intake to 1 g/kg body weight has been shown to minimise the progression of renal failure in the diabetic as well as the non-diabetic patient with excessive proteinuria (> 3 g/day). Sodium and potassium intake should be restricted to 2 g per day to avoid salt loading and hyperkalaemia.

2. Control blood pressure—another remedy that has proven efficacy in retarding the progression of renal failure is the strict control of blood pressure, with a target blood pressure of 120/75 mmHg. This can be achieved with ACE inhibitor therapy, but alternative agents such as ARBs or calcium channel blockers can be used.

3. Salt restriction and loop diuretics—hypertension and volume overload can be managed with salt restriction and loop diuretics. Blood pressure control can be particularly difficult in these patients, and treatment with multiple antihypertensive agents may be necessary.

4. Anaemia of chronic renal failure—can be well managed with erythropoietin injections given subcutaneously once or twice a week. Darbepoetin alpha is a novel agent that can be used in this regard. Erythropoietin therapy should be commenced when the haematocrit falls below 30%. Common side effects of erythropoietin therapy are headache, encephalopathy and hypertension. Failure of haemoglobin to normalise despite adequate erythropoietin therapy would be due to haematinic deficiency (particularly iron, vitamin B12, folate or vitamin C), hyperparathyroidism, sepsis, bleeding or malignancy. Iron deficiency is common among renal failure patients because their gastrointestinal iron absorption is usually impaired. Hence regular IV iron infusions should be carried out as guided by the serum iron indices. All renal failure patients should be supplemented with vitamin B complex (together with vitamin B12 and folate) and vitamin C daily.

5. Renal osteodystrophy—needs particular attention. Renal failure patients suffer from hyperphosphataemia and hypocalcaemia. To manage these electrolyte abnormalities, these patients should be placed on a low-phosphate diet and given phosphate binders such as calcium carbonate or calcium acetate to be taken with meals. They should also be given 1,25-(OH)2D3 (calcitriol) supplements.

6. Acidosis—could become a difficult management problem, and the ideal treatment would be chronic oral sodium bicarbonate therapy. Patients can inadvertently be given a significant salt load with this therapy. Therefore, be alert to the development of pulmonary oedema and hypertension. Acidosis can manifest as hyperkalaemia, lethargy and dyspnoea.

7. Cardiovascular status—mortality of most patients with renal failure is due to a cardiovascular event. Therefore it is extremely important to investigate the cardiovascular status and the risk profile of the patient. Check the cholesterol level, fasting blood sugar level and Hb A1c level. Perform an echocardiogram to study left ventricular wall anatomy, myocardial function and valvular anatomy and function. Perform a stress test or a perfusion study if the patient complains of ischaemic symptoms such as exertional angina.

8. Team approach—management of the patient with chronic renal failure should be done with the full participation of a qualified and experienced multidisciplinary team, including the physician (nephrologist), clinical nurse consultant or educator, dietitian, social worker, occupational therapist and a psychologist.

Renal osteodystrophy

Renal osteodystrophy is a specific condition about which some knowledge would be very useful. There are five broad types of abnormalities in bone metabolism associated with chronic renal failure that come to play in this situation:

• hyperparathyroid bone disease, leading to excessive bone resorption and cyst formation

• osteoporosis, with decreased bone mineral density

• osteomalacia

• osteosclerosis

• adynamic bone disease, where bone formation as well as bone resorption is impaired.

Other complications of chronic renal failure

1. Platelet dysfunction—can cause a coagulopathy leading to bruising and epistaxis

2. Dermatological problems—such as pigmentation and pruritus. Pruritus is due to a combination of hypercalcaemia, hyperphosphataemia, hyperparathyroidism and iron deficiency.

3. Gastrointestinal complications—such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, peptic ulcer disease, acute pancreatitis and constipation

4. Endocrinological problems—such as amenorrhoea, erectile dysfunction and infertility

5. Neurological complications—such as peripheral neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, confusion, coma and seizures

6. Cardiovascular disorders—such as pericarditis, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, congestive cardiac failure and myocardial fibrosis

7. Urinary symptoms—such as nocturia and polyuria

8. Gouty arthritis—due to hyperuricaemia

9. Hypercholesterolaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia and insulin resistance

10. Pancreatitis

11. Renal osteodystrophy

To help remember these problems, they can be rearranged by forming the mnemonic: A B C D E P, which stands for:

Hyperparathyroidism of renal failure is a compensatory response to alterations in calcium and phosphate metabolism in chronic renal failure, and generally can be attributed to decreased absorption of calcium due to decreased production of 1,25(OH)D3 by the failing kidney, phosphate retention with diminishing GFR, and alteration in free calcium levels by the shifts in the calcium phosphate product. This results in decreased calcium levels and high phosphate levels, and both stimulate parathyroid hormone production—Ca by the calcium receptor and PO4 by a direct effect on gene induction.

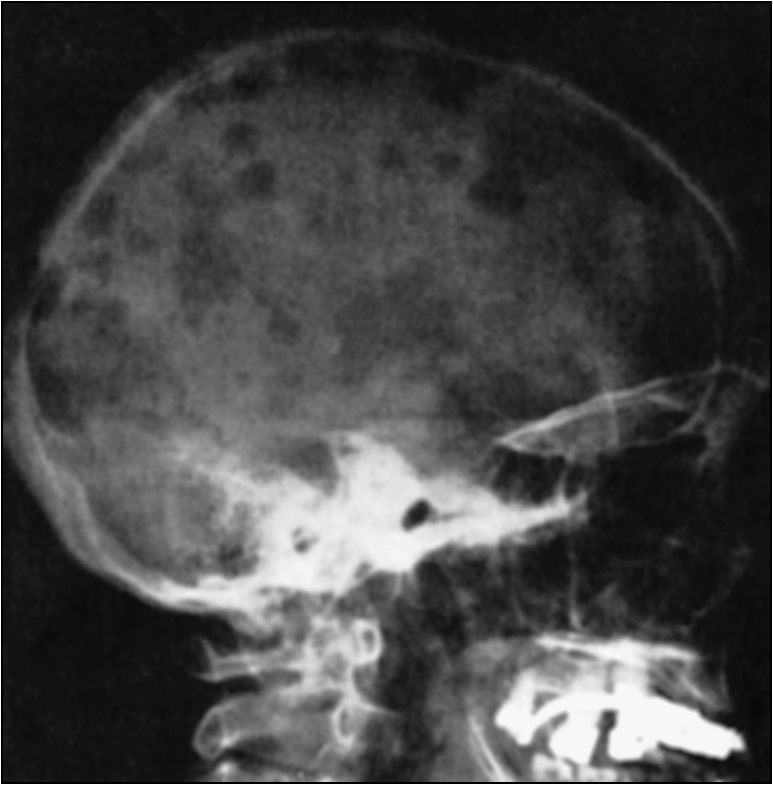

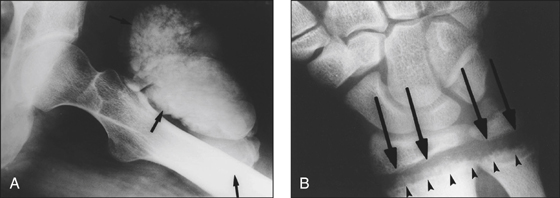

Secondary hyperparathyroidism causes osteitis fibrosis cystica due to the increased activity of the osteoclasts. This manifests as digital subperiosteal erosions and a ‘pepper pot’ appearance of the skull in X-ray images (Figs 6.3, 6.4). Hyperparathyroidism also causes osteosclerosis. Long-standing secondary hyperparathyroidism evolves into tertiary hyperparathyroidism, leading to semi-autonomous hypersecretion of parathyroid hormone that is related to the volume of the gland. Osteomalacia is now rarely seen, because of the reduced use of aluminium-based phosphate binder. Adynamic bone disease is now increasing and, while the cause is yet to be fully determined, it seems that overtreatment of hyperparathyroidism may be a factor (i.e. some degree of hyperparathyroidism seems to give protection from adynamic bone disease).

Figure 6.4 X-ray of renal osteodystrophy (A) Calcified ‘tumoral’ paraarticular masses (arrows) (B) Rickets-like changes in renal osteodystrophy. Widening of the physes (arrows) and cupping, widening, disorganisation and demineralisation of the metaphyses (arrowheads)(reprinted from Jevtic V 2003 Imaging of renal osteodystrophy. European Journal of Radiology 46:11)

Dialysis planning

Renal replacement is usually begun when the GFR falls below 10 mL/min. This can be timed and projected by plotting 1/(serum creatinine in mmol/L) against time in months. When the level falls below 1.3 mL/min, dialysis is usually commenced. A multidisciplinary team approach (as described above) is important in dialysis planning.

Principles of renal replacement are:

Be ready to discuss issues related to placing the patient on the transplant list and issues of immunosuppression (further discussed in Long case 4).

Indications for renal replacement therapy

The absolute and acute indications for renal replacement therapy are:

• Hyperkalaemia with K+ > 6.5 (or rapidly rising K+ levels) not responding to medical measures

• Uraemic pericarditis

• Uraemic pleurisy

• Uraemic encephalopathy of any form and acute uraemic neuropathy

• Bleeding diathesis secondary to severe uraemia—this is also described as an urgent and absolute indication

• Drug overdose—if the agent is amenable to dialysis

• Fluid overload resistant to diuretics

• Metabolic disturbances—including metabolic acidosis with pH < 7.1 not responding to other medical measures (others include hypercalcaemia, hypocalcaemia and hyperphosphataemia)

• Blood urea > 40.0 mmol/L tends to automatically trigger dialysis in an ICU setting, but not on the ward

• Persistent and intractable nausea and vomiting