112 Nephrolithiasis

• Ureteral calculi smaller than 5 mm in diameter spontaneously pass through the urinary tract in 90% of cases, whereas stones larger than 8 mm in diameter cause impaction in 95% of instances.

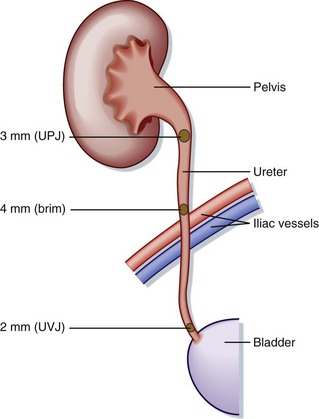

• Impaction most commonly occurs at the ureterovesical junction, the ureteropelvic junction, or the pelvic brim.

• Abdominal aortic aneurysms are commonly misdiagnosed as renal colic.

• Hematuria is absent in 15% of patients with symptomatic nephrolithiasis.

Scope and Outline

Renal colic is defined as severe, spasmodic pain caused by the impaction or passage of a calculus in the renal pelvis or ureter. Symptomatic nephrolithiasis will develop in approximately 15% of the U.S. population during their lives1; the majority of these patients seek treatment in the emergency department (ED).

Epidemiology

Most cases of renal colic occur in men between 20 and 50 years of age. The incidence of first-time ureteral stones in men is 0.3% per year, with recurrence rates of 37% and 50% at 1 and 5 years, respectively.2,3 The most significant risk factors for renal stone disease are listed in Box 112.1.

Pathophysiology

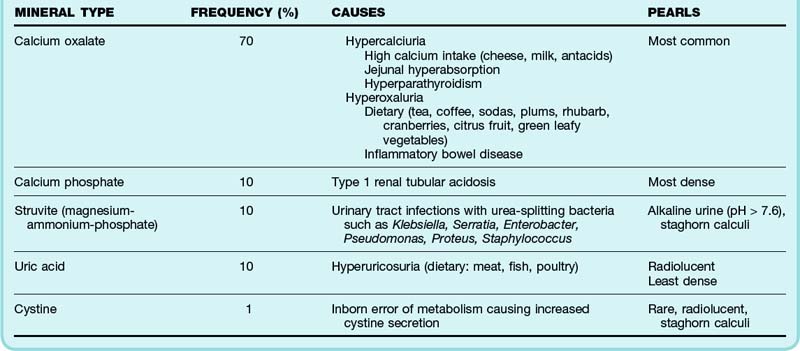

Renal stones form when the urine becomes supersaturated with calcium, oxalate, cystine, uric acid, or struvite. Hypercalciuria accounts for the development of 60% of calculi and results from increased intestinal absorption, decreased renal tubular reabsorption, or excessive bone resorption of calcium. Decreased urine output can further promote calculus formation as a result of reductions in citrate, magnesium pyrophosphate, and other inhibitors of urine crystallization. Table 112.1 describes features of the five main types of renal calculi.

Although an initial rise in creatinine may quickly resolve, irreversible kidney damage can begin to occur after 7 days of complete obstruction.3,4 Prolonged obstruction impairs recoverable kidney function over time,4,5 but case reports show that some recovery may be possible for up to 150 days.5,6

Ureteral obstruction is primarily determined by calculus size. Most stones smaller than 5 mm in diameter will pass spontaneously (90%), whereas passage of stones larger than 8 mm is unlikely (5%). Table 112.2 compares ureteral stone size with the percent likelihood of spontaneous passage.

Table 112.2 Renal Calculus Size and Likelihood of Spontaneous Passage

| STONE SIZE (DIAMETER) | PERCENT LIKELIHOOD OF SPONTANEOUS PASSAGE |

|---|---|

| <5 mm | 90 |

| 5-8 mm | 15 |

| >8 mm | 5 |

Anatomy

Stone impaction most commonly occurs at the ureterovesical junction, the narrowest part of the genitourinary tract. Other common areas of impaction include the ureteropelvic junction (where the renal pelvis narrows from 1 cm down to 3 mm) and the pelvic brim (where the ureter arches anteriorly across the iliac vessels) (Fig. 112.1).

Clinical Presentation

History

The location of the ureteral calculus determines the symptoms, as outlined in Table 112.3.

Table 112.3 Ureteral Calculus Location and Associated Symptoms

| LOCATION OF CALCULUS | SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|

| Renal pelvis or calyx | Deep flank ache |

| Proximal or middle part of the ureter | Severe flank pain radiating to the groin |

| Distal end of the ureter | Flank discomfort and/or low abdominal pain |

| Bladder | Dysuria, frequency, urgency, retention, suprapubic discomfort |

Physical Examination

Patients with renal colic typically appear uncomfortable and are commonly described as “writhing” on the gurney. Findings on the abdominal examination are generally unremarkable, although thin patients with distal ureteral stones and obstruction may exhibit some tenderness. Tenderness at the costovertebral angle can develop as a result of worsening hydronephrosis; this sign is mild or absent early in the course of the disease. Abnormal findings on physical examination should raise suspicion for alternative diagnoses, as reviewed in Table 112.4.

Table 112.4 Physical Examination Findings and Potential Alternative Diagnoses

| FINDING | CONSIDERATION |

|---|---|

| Vital Signs | |

| Fever | Infected stone, pyelonephritis, perinephric abscess |

| Hypotension | Sepsis, abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| Abdomen | |

| Bruit | Abdominal aortic aneurysm, renal artery stenosis |

| Pulsatile mass | Abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| Pronounced costovertebral angle tenderness | Pyelonephritis |

| Lower abdominal or pelvic tenderness | Ectopic pregnancy, appendicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, tuboovarian abscess, ovarian torsion |

| Genitourinary | |

| Testicular tenderness | Torsion, epididymitis, orchitis |

| Mass | Hernia, cancer |

| Pulmonary | |

| Focal findings | Lobar pneumonia |

| Cardiovascular | |

| Asymmetric lower extremity pulses | Abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| Skin | |

| Vesicular rash | Herpes zoster |

Differential Diagnosis

Many disease processes can mimic symptomatic nephrolithiasis. Abdominal aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, renal artery dissection, and renal infarction are the most lethal conditions that may manifest similar to renal colic. In one study, abdominal aortic aneurysms were initially misdiagnosed as kidney stones in approximately 20% of patients older than 60 years.7 Box 112.2 lists the differential diagnosis for renal colic.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory Tests

Urinalysis

Hematuria is a common but inconsistent finding in patients with ureteral stones. The amount of gross or microscopic hematuria does not correlate with stone impaction or the degree of obstruction; rather, hematuria results from direct ureteral trauma caused by the passing stone.8 Hematuria is absent in 15% of patients with ureteral stones.9,10

Imaging

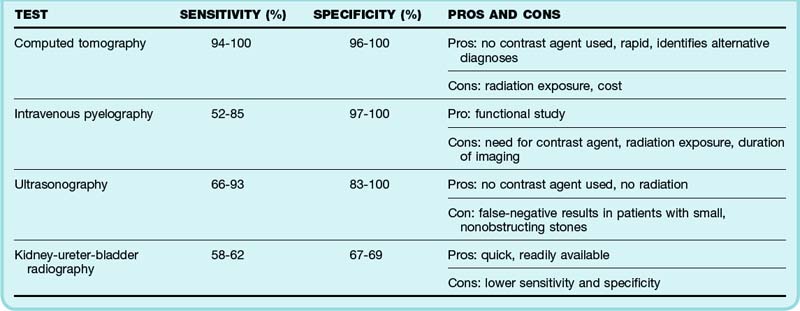

ED imaging (Table 112.5) is used to confirm the diagnosis of nephrolithiasis, evaluate stone size, identify obstruction, and exclude alternative diagnoses. Patients with decreased renal reserve (solitary kidney, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled hypertension), concurrent infection, first occurrence of stone disease, advanced age, and prolonged or unrelenting symptoms should undergo imaging during their initial evaluation. Indications for emergency imaging in cases of suspected renal colic are summarized in Table 112.6.

Table 112.6 Indications for Diagnostic Imaging of Patients with Suspected Renal Colic

| FINDING | INDICATION FOR DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING |

|---|---|

| Solitary kidney, uncontrolled diabetes,* uncontrolled hypertension* | To exclude obstruction in a patient with decreased renal reserve |

| Advanced age | To exclude alternative diagnoses, especially vascular disease |

| Concurrent infection | If concurrent with obstruction, a urologist should be involved to evaluate the need for intervention |

| Prolonged symptoms | To evaluate for prolonged obstruction, which may cause renal impairment |

| Refractory symptoms, first occurrence* | To exclude alternative diagnoses, especially ischemia or infarction |

Helical Computed Tomography

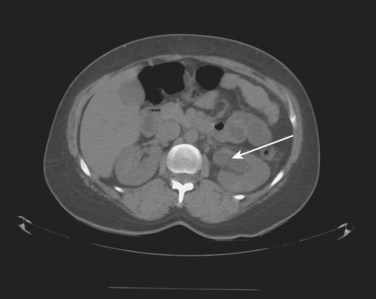

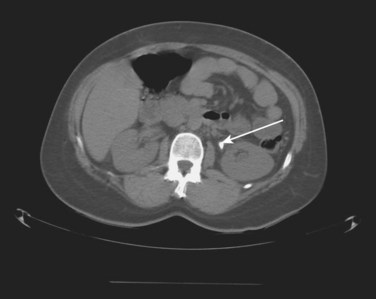

Noncontrast helical computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis is the preferred imaging modality for the evaluation of patients with suspected nephrolithiasis. CT imaging for renal stones can be performed without contrast material, demonstrates both high sensitivity (94% to 100%) and specificity (96% to 100%),11–15 and allows alternative diagnoses to be simultaneously identified.15,16 Sagittal images are obtained at 5-mm intervals from the top of the kidney to the bottom of the bladder (Figs. 112.2 and 112.3).

Intravenous Pyelography

Intravenous pyelography (Fig. 112.4) has a sensitivity of 52% to 85% and specificity of 97% to 100% for detection of ureteral calculi.11,17,18 It provides a visual interpretation of renal function, as well as genitourinary anatomy. The earliest sign of ureteral obstruction on an intravenous pyelogram is a delayed nephrogram; other abnormal findings include a “standing column” (the entire ureter seen on one image; Fig. 112.5), hydroureter, hydronephrosis, contrast cutoff at the point of impaction, and extravasation of contrast material. The use of intravenous pyelography is limited by the need for contrast material, decreased sensitivity in comparison with helical CT, and the length of time required to obtain multiple delayed images.

Sonography

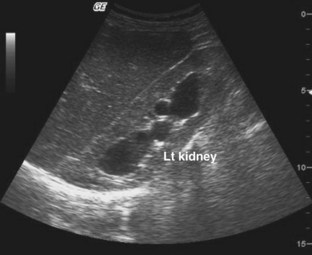

Ultrasonography is a useful modality for identifying hydronephrosis caused by ureteral obstruction (Fig. 112.6). Advantages include its ease of use and rapid acquisition of diagnostic images at the bedside without the need for contrast agents or radiation. It is the imaging technique of choice for the evaluation of suspected renal colic in pregnancy. Ultrasonography is limited by false-negative results, which occur in patients with small calculi that do not cause significant obstruction or hydronephrosis. The sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography for the diagnosis of urologic stone disease is 66% to 93% and 83% to 100%, respectively.18–20

Plain Radiography

The utility of plain radiography (kidney-ureter-bladder [KUB] projection performed in the supine position) is dependent on the radiodensity of the suspected kidney stone. Although 90% of stones are radiopaque (Fig. 112.7), uric acid and cystine calculi are radiolucent. KUB imaging is limited technically by overlying soft tissue, air, and bone; low sensitivity (58% to 62%) and specificity (67% to 69%) are observed in clinical practice.21,22 The combination of ultrasonography and KUB radiography improves the usefulness of these imaging modalities. Studies that used both ultrasound and plain radiography for the detection of nephrolithiasis demonstrated a sensitivity and specificity of 89% and 100%, respectively, when both tests were positive20 and a sensitivity and specificity of 95% and 67%, respectively, when either test was positive.23

Treatment

Pharmacologic Management

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) decrease ureteral spasm by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis. Renal blood flow may be reduced when NSAIDs are administered in the setting of ureteral obstruction,24 thereby improving symptoms through a decrease in urine production and ureteric pressure. Ketorolac (Toradol) (30 mg intravenously or 60 mg intramuscularly) has efficacy equivalent to the oral administration of 800 mg of ibuprofen, although the latter may be less well tolerated in patients with concomitant nausea.

Opiates

Intravenous narcotics provide adequate relief of symptoms for most patients with renal colic. Opiates have similar analgesic effects at equivalent dosing. Although meperidine (Demerol) demonstrates smooth muscle relaxation when tested in vitro,25 this spasmolytic effect does not appear to improve its clinical utility in therapy for renal colic.26 Given the potential for drug interactions with meperidine, preferred opiates for ED use include hydromorphone (0.015 mg/kg) and morphine (0.1 mg/kg starting dose).

Tips and Tricks

A young, healthy patient with the typical findings of renal colic, a history of previous nephrolithiasis, no signs of infection, and easily managed symptoms may be discharged with analgesics, antiemetics, and a urine strainer for follow-up within 7 days.

All other patients require evaluation of the need for imaging and possible urology consultation.

Multiple studies have shown that both NSAIDs and opiates are effective and appropriate treatments of renal colic.24–31 One metaanalysis of 19 studies showed that NSAIDs and opiates are equally effective in the acute management of renal colic symptoms.28 Many experts recommend the use of NSAIDs followed by opiates for continued pain.

Management of Other Symptoms

Tamsulosin (Flomax), an α-adrenergic blocker, reduces ureteral spasm. Early studies suggested that oral tamsulosin (0.4 mg/day) helps promote ureteral passage of juxtavesical stones.32 There continue to be more studies supporting such treatment,33–35 as well as studies now indicating that tamsulosin may be useful for more proximal stones as well.36 Calcium channel blockers have been studied for their smooth muscle relaxant effects, and some studies suggest that they also promote stone expulsion.34,37,38

Antiemetics should be administered to patients experiencing concomitant nausea or vomiting. Intravenous crystalloid administration was once thought to promote stone migration by stimulating ureteral peristalsis; however, no supporting evidence has shown that hydration consistently improves symptoms by this mechanism.39

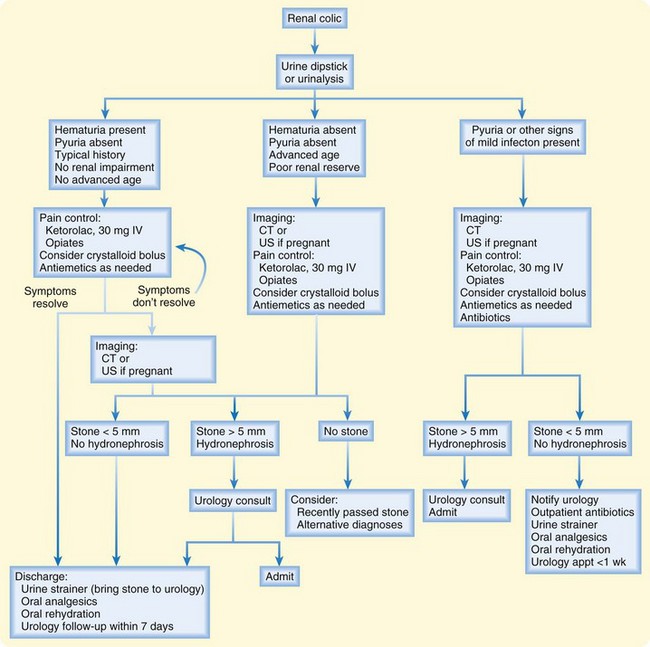

Disposition

Patients with uncomplicated renal colic whose symptoms are easily controlled should be discharged with analgesics, a urine strainer, antiemetics, and follow-up within 7 days. Stones captured by urine straining should be brought to the urologist for pathologic evaluation. Return precautions include uncontrolled pain, protracted vomiting, and fever (Fig. 112.8).

Box 112.3 summarizes common indications for admission or urology consultation.

1 Trivedi B. Nephrolithiasis: how it happens and what to do about it. Nephrolithiasis. 1996;100:63–78.

2 Ahlstrand C, Tiselius H. Recurrences during a 10-year follow-up after first renal stone episode. Urol Res. 1990;18:397–399.

3 Kerr Jr, WS. Effect of complete ureteral obstruction for one week on kidney function. J Appl Physiol. 1954;6:762–772.

4 Vaughan E, Gillenwater J. Recovery following complete chronic unilateral ureteral occlusion: functional, radiographic and pathologic alterations. J Urol. 1971;106:27–35.

5 Shapiro S, Bennett A. Recovery of renal function after prolonged unilateral ureteral obstruction. J Urol. 1976;115:136–140.

6 Okubo K, Suzuki Y, Ishitoya S, et al. Recovery of renal function after 153 days of complete unilateral ureteral obstruction. J Urol. 1998;160:1422–1423.

7 Borrero E, Queral LA. Symptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm misdiagnosed as nephroureterolithiasis. Ann Vasc Surg. 1988;2:45–49.

8 Stewart D, Kowalski R, Wong P, et al. Microscopic hematuria and calculus-related ureteral obstruction. J Emerg Med. 1990;8:693–695.

9 Luchs J, Katz D, Lane M, et al. Utility of hematuria testing in patients with suspected renal colic: correlation with unenhanced helical CT results. Urology. 2002;59:839–842.

10 Press S, Smith A. Incidence of negative hematuria in patients with acute urinary lithiasis presenting to the emergency room with flank pain. Urology. 1995;45:753–757.

11 Yilmaz S, Sindel T, Arslan S, et al. Renal colic: comparison of spiral CT, US and IVP in the detection of ureteral calculi. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:212–217.

12 Fielding J, Steele G, Fox L, et al. Spiral computerized tomography in the evaluation of acute flank pain: a replacement for excretory urography. J Urol. 1997;157:2071–2073.

13 Dalrymple N, Verga M, Anderson K, et al. The value of unenhanced helical computerized tomography in management of acute flank pain. J Urol. 1998;159:735–740.

14 Boulay I, Holtz P, Foley W, et al. Ureteral calculi: diagnostic efficacy of helical CT and implications for treatment of patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:1485–1490.

15 Smith R, Verga M, McCarthy S, et al. Diagnosis of acute flank pain: value of unenhanced helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:97–101.

16 Colistro R, Torreggiani W, Lyburn I, et al. Unenhanced helical CT in the investigation of acute flank pain. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:435–441.

17 Sourtzis S, Thibeau J, Damry N, et al. Radiologic investigation of renal colic: unenhanced helical CT compared with excretory urography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:1491–1494.

18 Hill M, Rich J, Mardiat J, et al. Sonography vs excretory urography in acute flank pain. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:1235–1238.

19 Patlas M, Farkas A, Fisher D, et al. Ultrasound vs CT for the detection of ureteric stones in patients with renal colic. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:901–904.

20 Gorelik U, Ulish Y, Yagil Y. The use of standard imaging techniques and their diagnostic value in the workup of renal colic in the setting of intractable flank pain. Urology. 1996;47:635–642.

21 Mutgi A, Williams J, Nettleman M. Utility of the plain abdominal roentgenogram. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1589–1592.

22 Roth C, Bowyer B, Berquist T, et al. Utility of the plain abdominal radiography for diagnosing ureteral calculi. Ann Emerg Med. 1985;14:311–315.

23 Palma L, Stacul F, Bazzocchi M, et al. Ultrasonography and plain film versus intravenous urography in ureteric colic. Clin Radiol. 1993;47:333–336.

24 Perlmutter A, Miller L, Trimble LA, et al. Toradol, an NSAID used for renal colic, decreases renal perfusion and ureteral pressure in a canine model of unilateral ureteral obstruction. J Urol. 1993;149:926–930.

25 Lennon G, Bourke J, Ryan P, et al. Pharmacological options for the treatment of acute ureteric colic. Br J Urol. 1993;71:401–407.

26 Jasani NB, O’Conner RE, Bouzoukis JK. Comparison of hydromorphone and meperidine for ureteral colic. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1:539–543.

27 Cordell W, Larson T, Lingeman J, et al. Indomethacin suppositories versus intravenously titrated morphine for the treatment of ureteral colic. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:262–269.

28 Labrecque M, Dostaler L, Rousselle R, et al. Efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of acute renal colic. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1381–1387.

29 Lundstam SO, Leissner KH, Wåhlander LA, et al. Prostaglandin-synthetase inhibition with diclofenac sodium in treatment of renal colic: comparison with use of a narcotic analgesic. Lancet. 1982;1:1096–1097.

30 Larkin G, Peacock W, Pearl S, et al. Efficacy of ketorolac tromethamine versus meperidine in the ED treatment of acute renal colic. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:6–10.

31 Cordell W, Wright S, Wolfson A, et al. Comparison of intravenous ketorolac, meperidine, and both (balanced analgesia) for renal colic. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:151–158.

32 Dellabella M, Milanese G, Muzzonigro G. Efficacy of tamsulosin in the medical management of juxtavesical ureteral stones. J Urol. 2003;170:2202–2205.

33 Duquenne S, Hellel M, Godinas L, et al. Spasmolytics indication in renal colic: a literature review. Rev Med Liege. 2009;64:45–48.

34 Singh A, Alter H, Littlepage A. A systematic review of medical therapy to facilitate passage of ureteral calculi. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:552–563.

35 Dellabella M, Milanese G, Muzzonigro G. Randomized trial of the efficacy of tamsulosin, nifedipine and phloroglucinol in medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteral calculi. J Urol. 2005;174:167–172.

36 Yencilek F, Erturhan S, Canguven O, et al. Does tamsulosin change the management of proximally located ureteral stones? Urol Res. 2010;38:195–199.

37 Welk B, Teichman J. Pharmacological management of renal colic in the older patient. Drugs Aging. 2007;24:891–900.

38 Troxel S, Jones A, Magliola L, et al. Physiologic effect of nifedipine and tamsulosin on contractility of distal ureter. J Endourol. 2006;20:565–568.

39 Edna T, Hesselberg F. Acute ureteral colic and fluid intake. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1983;17:175–178.