Chapter 493 Neoplasms of the Kidney

493.1 Wilms Tumor

Peter M. Anderson, Chetan Anil Dhamne, and Vicki Huff

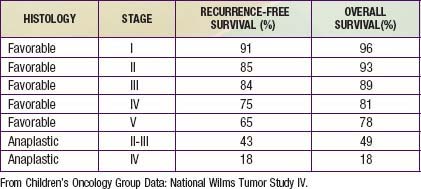

Wilms tumor, also known as nephroblastoma, is the most common primary malignant renal tumor of childhood; other tumors are very rare. Use of multimodality treatment and multi-institutional cooperative group trials has dramatically improved the Wilms tumor cure rate from <30% to ≈90% (Table 493-1).

Etiology: Genetics and Molecular Biology

Wilms tumor is genetically heterogeneous (Table 493-2). Familial Wilms tumors have been linked to FWT1 gene at chromosome 17q and FWT2 gene at chromosome 19q13. However, some families carry neither of these mutations, suggesting that additional Wilms tumor loci exist.

| SYNDROME | CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS | GENETIC ANOMALIES |

|---|---|---|

| Wilms tumor, aniridia, genitourinary abnormalities, and mental retardation (WAGR syndrome) | Aniridia, genitourinary abnormalities, mental retardation | Del 11p13 (WT1 and PAX6) |

| Denys-Drash syndrome | Early-onset renal failure with renal mesangial sclerosis, male pseudohermaphrodism | WT1 missense mutation |

| Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) | Organomegaly (liver, kidney, adrenal, pancreas) macroglossia, omphalocele, hemihypertrophy | Unilateral paternal disomy, duplication of 11p15.5 loss of imprinting, mutation of p57KIP57 Del 11p15.5 IGF2 and H19 imprinting control region |

Epidemiology

The incidence of Wilms tumor is approximately 8 cases/million children <15 yr of age with about 500 new cases in North America per year. It accounts for nearly 6% of pediatric malignancies and is the second most common malignant abdominal tumor in childhood. Although peak incidence is between 2 and 5 yr of age, Wilms tumor has also been encountered in neonates, adolescents, and adults. It can arise in one or both kidneys. The incidence of bilateral Wilms tumors is 7%, and individuals with horseshoe kidney are at twice the risk for development of Wilms tumor as the general population. Wilms tumor may be associated with hemihypertrophy, aniridia, genitourinary anomalies, and a variety of rare syndromes (see Table 493-2), including BWS and Denys Drash syndrome.

Clinical Presentation

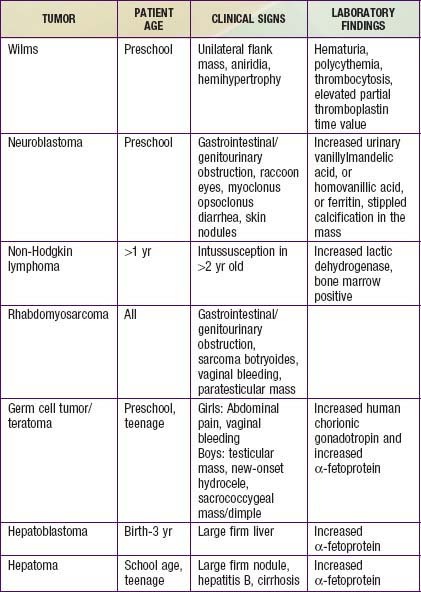

The most common initial clinical presentation for Wilms tumor is the incidental discovery of an asymptomatic abdominal mass by parents while bathing or clothing an affected child or by a physician during the course of a routine physical examination (Table 493-3). At presentation the mass can be quite large because retroperitoneal masses can grow unhampered by strict anatomic boundaries. Functional defects in paired organs like the kidney, with good functional reserve, are also unlikely to be detected early. Hypertension is detected in about 25% of tumors at presentation. Renin production by the tumor itself has been suggested as the cause. Elevated renin values are also attributed to renal ischemia caused by either pressure from the tumor directly on the renal artery or indirectly as a result of tumor compression within the renal capsule or by intrarenal arteriovenous fistula formation. But the etiology remains unknown in majority of the cases. Some patients present with abdominal pain. About 15- 25% of cases have hematuria, usually asymptomatic. Occasionally rapid abdominal enlargement and anemia occur as a result of bleeding into the renal parenchyma or pelvis. Wilms tumor thrombus extends into the inferior vena cava in 4-10% of patients, and rarely into the right atrium. Patients might also have microcytic anemia from iron deficiency or anemia of chronic disease, polycythemia, elevated platelet count, and acquired deficiency of von Willebrand factor or factor VII deficiency.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

An abdominal mass in a child should be considered malignant until diagnostic imaging, laboratory finding, and/or pathology can define its true nature (see Table 493-3). Imaging studies include abdominal flat plate radiography, abdominal ultrasonography (US), CT, and/or MRI of the abdomen to define the intrarenal origin of the mass and differentiate it from adrenal masses (e.g., neuroblastoma) and other masses in the abdomen. Abdominal US helps differentiate solid from cystic masses. Wilms tumor might show focal areas of necrosis or hemorrhage and hydronephrosis due to obstruction of the renal pelvis by the tumor. US with Doppler imaging of renal veins and the inferior vena cava is a useful first study that can not only look for Wilms tumor but also evaluate the collecting system and demonstrate tumor thrombi in the renal veins and/or inferior vena cava.

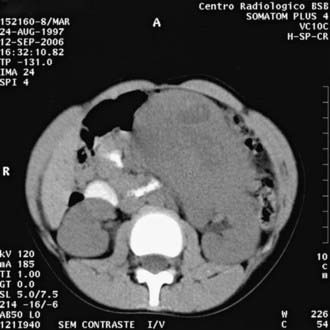

CT (Fig. 493-1) and/or MRI is useful to define the extent of the disease, integrity of the contralateral kidney, and metastasis. In bilateral cases, MRI may be a better guide to nephron-sparing surgery. If histologic diagnosis confirms clear cell sarcoma of the kidney, a bone scan is indicated. A brain MRI is indicated in case of rhabdoid tumor of the kidney, to look for metastasis. Chest CT is more sensitive than chest radiography to screen for and characterize pulmonary metastasis in Wilms tumor and other solid tumors.

Treatment

Prognostic factors for risk-adapted therapy include age, stage, tumor weight, and loss of heterozygosity at chromosomes 1p and 16q (Table 493-4). Histology plays a major role in risk stratification of Wilms tumor. Absence of anaplasia is considered a favorable histologic finding. Presence of anaplasia is further classified as focal or diffuse, both of which are unfavorable histologic findings.

| Stage I | Tumor confined to the kidney and completely resected. Renal capsule or sinus vessels not involved. Regional lymph nodes dissected and negative. |

| Stage II | Tumor extends beyond the kidney but is completely resected with negative margins and lymph nodes. At least one of the following has occurred: (a) penetration of renal capsule, (b) invasion of renal sinus vessels. |

| Stage III | Residual tumor present following surgery confined to the abdomen, including inoperable tumor; positive surgical margins; spillage of tumor preoperatively or intraoperatively; biopsy prior to nephrectomy, regional lymph node metastases; extension of tumor thrombus into the inferior vena cava including thoracic vena cava and heart. |

| Stage IV | Metastases outside the abdomen, for example, lung. |

| Stage V | Bilateral renal tumor. |

Source: Children’s Oncology Group Protocol AREN 0532.

493.2 Other Pediatric Renal Tumors

Ahmed HU, Arya M, Levitt G, et al. Part I: Primary malignant non-Wilms’ renal tumours in children. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:730-737.

Ahmed HU, Arya M, Levitt G, et al. Part II: Treatment of primary malignant non-Wilms’ renal tumours in children. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:842-848.

Baxter PA, Nuchtern JG, Guillerman RP, et al. Acquired von Willebrand syndrome and Wilms tumor: not always benign. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52:392-394.

D’Angio GJ. The National Wilms Tumor Study: a 40 year perspective. Lifetime Data Anal. 2007;13:463-470.

Davidson A, Hartley PS, Shuttleworth MH. Erythrocytosis and iron deficiency anemia in Wilms tumor. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27:502.

Fukuzawa R, Reeve AE. Molecular pathology and epidemiology of nephrogenic rests and Wilms tumors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;9:589-594.

Kaste SC, Dome JS, Babyn PS, et al. Wilms tumour: prognostic factors, staging, therapy and late effects. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:2-17.

Pritchard-Jones K, Pritchard J. Success of clinical trials in childhood Wilms’ tumour around the world. Lancet. 2004;364:1468-1470.

Scott RH, Douglas J, Baskcomb L, et al. Constitutional 11p15 abnormalities, including heritable imprinting center mutations, cause nonsyndromic Wilms tumor. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1329-1334.

Sonn G, Shortliffe LM. Management of Wilms tumor: current standard of care. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2008;5:551-560.