Chapter 49 Neoplasms Around the Elbow

Introduction

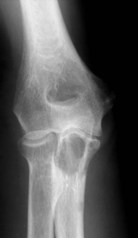

The elbow appears to be an area which is rarely afflicted by primary bone tumours. Although it is difficult to give a true incidence of the conditions, a review of 2900 cases referred to the London Bone Tumour Service reveals only 39 cases involving the elbow joint. The pathological diagnoses of these cases are shown in the Table 49.1. Although this table may represent the true incidence of primary malignant lesions in the southern half of the UK, it does not reflect the true incidence of benign lesions, many of which will be treated without referral to a supra-specialist centre. Finally the most frequent lesion seen around the elbow joint will in fact be a metastasis, particularly in a patient over 40, the primary lesion being either in the breast, prostate, bronchus, kidney or thyroid (Fig. 49.1). Pathological fracture is not an unusual mode of presentation (Fig. 49.2).

Table 49.1 London Bone Tumour Service: pathological diagnoses of cases involving the elbow

| Eventual diagnosis | No |

|---|---|

| Ewing’s/malignant round cell tumour | 8 |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst | 6 |

| Osteoblastoma | 2 |

| Giant cell tumour | 1 |

| Chondroblastoma | 1 |

| Metastasis | 6 |

| Others | 15 |

| Total (elbow) | 39 |

| Total cases (all sites) | 2900 |

Background/aetiology

The most common benign lesion of bone is undoubtedly the solitary osteocartilaginous exostosis (osteochondroma). This condition was first described by Sir Astley Cooper in 1818.1 A review of 323 solitary lesions throughout the skeleton revealed only five around the distal humerus.2 In multiple exostoses (diaphyseal aclasis) the distal humerus, in common with other long tubular bones, may be affected and unequal growth of the bones about the elbow may cause radiohumeral subluxation.3 Diaphyseal aclasis must be distinguished from Ollier’s disease or multiple enchondromatosis. This is a cartilage dysplasia which rarely affects the elbow region, although involvement of a bone close to an epiphysis may lead to forearm distortion.4 The association of soft tissue haemangiomas with chondromatosis is known as Maffucci’s syndrome.5,6 Any bone or area may be affected and the rate of malignant transformation of the enchondritic element is said to be greater than in Ollier’s disease.

Sir Astley Cooper is also credited with the first description of a giant cell tumour and emphasized its benign nature, although the French surgeon, Nelaton, was the first to give a good account of the varied clinical course and histological features.7 A review of 265 cases of giant cell tumour finds only three occurring around the distal humerus.

None of the four common primary bone malignancies – osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma – are commonly found around the elbow joint. Sir James Paget first described osteosarcoma in 1854.8 Until the mid-1970s, treatment had always been by ablation, but with modern chemotherapy, limb-sparing surgical techniques may be attempted. Ewing first described his eponymous disease in 19219 and further classified telangiectatic osteosarcoma in 1922.10 The disease which bears his name is now thought to have been originally recognized by Lucke in 1866.11 It is considered to be one of a spectrum of small round cell tumours to afflict bone. Considerable skill and immunocytochemistry may be required for a histopathologist to differentiate Ewing’s sarcoma from neuroblastoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumour of bone, small cell osteosarcoma, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and lymphoma of bone.

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

Bone-forming tumours

Benign

Osteoid osteoma

This condition usually presents as vague pain, often nocturnal characteristically relieved by aspirin or other non-steroidal antiinflammatory agents.12 The pain may be associated with tenderness and vasomotor disturbance. Classically, the osteoblastic nidus arises within the cortex or spongiosa of long bones. The nidus is less than 1 cm in diameter and induces dense surrounding change. If the nidus is in a subarticular location diagnosis can be difficult as the reactive changes may not occur. Intracapsular osteoid osteomas around the elbow have been mistaken for tuberculous synovitis13 and rheumatoid arthritis.14 It is also well recognized that longstanding disease can induce degenerative changes (Fig. 49.3).15

The radiological investigation consists initially of a plain X-ray. This may or may not reveal the characteristic nidus. When marked reactive bone is seen, the differential diagnosis is between bone abscess, sclerosing osteomyelitis of Garré, osteochondritis and stress fracture.16 Bone scintigraphy will usually help localize a nidus, but is relatively non-specific. Classically the area has two levels of activity. Computed tomography (CT) if performed in close 2 mm sections, will be successful in accurately locating the nidus prior to surgical resection or ablation.17

The treatment of osteoid osteoma requires excision or ablation of the nidus. As the nidus is surrounded by dense reactive bone, this can be difficult to achieve. The traditional approach requires wide exposure with radiological verification of the site. More recently the use of intra-operative scintigraphy has been described, although this is rarely required.18 Excisional biopsy of the nidus under CT control is now being successfully performed (Johnson and Cannon, manuscript in preparation). In addition, radiofrequency ablation is now being undertaken with encouraging results. The latter is performed by radiologists under CT control, the only real contraindication being where the nidus is adjacent to either vascular or neural tissue.19,20

Osteoblastoma

This is a similar lesion histologically to osteoid osteoma, although larger and not inducing so much reactive surrounding change. It is an extremely rare lesion affecting mainly the axial skeleton, although any bone may be affected. Patients are predominantly male in their second or third decades.21

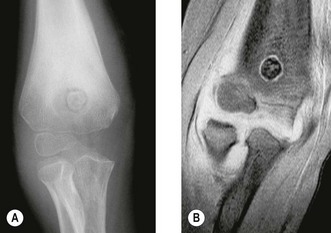

The clinical presentation is of vague pain, less marked than osteoid osteoma, and not particularly relieved by salicylates. Occasionally there may be both swelling and joint dysfunction. The radiological features classically show an expansile lesion, radiolucent with a thin shell of peripheral new bone (Fig. 49.4).

Figure 49.4 (A) Anteroposterior X-ray and (B) computed tomography scan, showing osteoblastoma of the proximal ulna.

Treatment consists of either curettage with or without bone grafting or local excision. Local excision gives good local control but reconstruction may be required. Recurrence rate may be as high as 20% following curettage, although the use of radiotherapy in extra-spinal cases is rarely required.22

Malignant

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary bone tumour and can occur at any age, although most cases occur in the first two decades of life.23 Although commonly affecting the metaphysis around the knee, the humerus is the third most frequently affected bone, with tumours often arising at an earlier age than in the lower limb, and usually affecting the proximal metaphyseal area.24

Osteosarcomas are usually subtyped on the basis of their histological patterns into fibroblastic, chondroblastic, telangiectatic or mixed. Although the subtype was originally thought to have a bearing on prognosis, more recently carefully controlled studies have shown this is not to be the case.25 Histological grading as a prognostic indication is also unreliable.26

Patients usually present with a short history of pain followed by swelling and joint dysfunction. Occasionally they can present with a pathological fracture. The many radiological advances which have occurred in the last decade have allowed very accurate staging of the disease. Plain X-rays remain the primary diagnostic tool but can underestimate the extent of the tumour. CT scanning will give a more accurate visualization of cortical destruction and soft tissue spread but may miss skip lesions in the same bone. It is a useful technique in planning biopsy and local excisions.27 The accepted staging investigation to assess for the presence of pulmonary metastases is CT of the chest. Local staging of disease depends heavily on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the whole bone. This, particularly in T2 mode, will delineate accurately the intramedullary extent and soft tissue extent of the lesion. It will outline the relationship of the tumour to the adjacent joints and to the blood vessels.

Preoperative bone scanning using technetium isotopes is useful in identifying skip lesions and metachronous lesions in other bones. A radioisotope scan may also on occasions, demonstrate pulmonary metastases.28 Having performed the radiological staging procedures, it is necessary to establish the pathological diagnosis. For this a biopsy is required. Many argue that this should be an open biopsy. However, Stoker et al29 have shown the accuracy of Jamshidi needle biopsy cores obtained under local anaesthesia and image intensification. This can also be supplemented by other imaging techniques.

Historically, the treatment of osteosarcoma has always been surgical ablation. In the upper limb this has led to either disarticulation at the shoulder for lesions in the distal humerus or forequarter amputation for more proximal growths. Survival, however, has been poor with 5-year survival rates varying between 11% and 25%. Cade30 reported an alternative method of treatment combining preoperative radiation followed by surgical ablation in cases without pulmonary metastases. Fewer amputations were performed but the survival rate was unaltered. This has subsequently been confirmed by other series.31

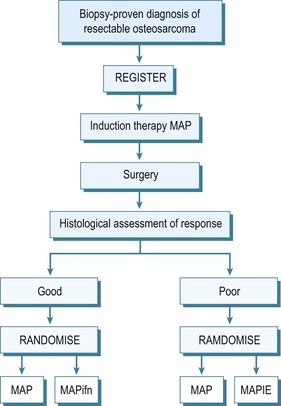

By the early 1970s it became evident that this appalling survival rate might be improved by the use of adjuvant chemotherapy. Many different protocols were produced, some claiming very high survival rates,32 although controlled trials of therapies were not performed. In the UK the Medical Research Council combined with the European Organisation for Research into Cancer Treatment (EORTC) set up controlled trials of adjuvant chemotherapy. These have advanced to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which allows treatment of undetected micro-metastases and causes necrosis of the tumour which may result in some shrinkage of the primary tumour. This latter effect may allow easier local resection and reconstruction of the limb. The initial trials compared the effect of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cisplatin with or without high-dose methotrexate. The two-drug combination performed better, giving a survival of 65% at 5 years. This combination has also been compared with a Rosen T10 regimen. The trial assessed 400 cases and analysis revealed significant difference between the treatment modalities. A further trial into which all osteosarcoma cases without metastases were entered was an attempt at dose intensification using the rescue factor granulocyte cell stimulating factor. It aimed to allow three courses of chemotherapy to be given in 6 rather than 9 weeks. This trial unfortunately did not show any major difference in survival. Currently an international randomized trial is ongoing for the aim of optimizing treatment strategies for resectable osteosarcoma based on histological response. Effectively those with a good early response to induction chemotherapy, which consists of methotrexate, Adriamycin and cisplatin, are randomized to a standard arm of the same therapy in the postoperative period plus or minus interferon, whereas for those that are recognized to have a poor response, chemotherapy is enhanced with the addition of ifosfamide and etoposide.33 The outline of this regimen in seen in Figure 49.5.

Parosteal osteosarcoma

This is a low-grade malignant tumour which develops on the external surface of large bones. The disease was first reported by Geschickter and Copeland in 1951.34 It has a long natural history and tends to affect patients in the second and third decades of life. Most patients present with a long-standing swelling associated with a dull ache. The elbow is only rarely affected.

Treatment consists of wide local resection of the tumour with appropriate reconstruction. It is generally accepted that in most cases chemotherapy is not indicted. Histological analysis of the tumour may show high-grade changes in the fibrous elements. These tumours have a poor prognosis,35 and chemotherapy may be indicated. Occasionally the low-grade component may transform or dedifferentiate to a high-grade osteosarcoma. Treatment is then as for an osteosarcoma.36

Periosteal osteosarcoma

This is a very rare tumour, with many still doubting its existence,37 although it probably is a variant of parosteal osteosarcoma with a prominent cartilaginous component.38 These are usually small unicortical lesions. Treatment is by wide resection and appropriate reconstruction. Whether chemotherapy is required in their management is still unclear.

Cartilage forming tumours

Benign

Osteochondroma

These cartilage-capped bony protrusions may develop in any bone derived from cartilage. They are usually discovered in childhood and many are found only as incidental findings on radiology. They are usually painless, although discomfort can be invoked by mechanical irritation or nerve compression. A pseudoaneurysm has also been reported specifically in the popliteal region.39

In diaphyseal aclasis the patient may also present with growth abnormality and subluxation at the radiohumeral joint. In this condition, removal of the lesions is rarely enough and the patients often require major reconstructions to correct the deformities.40 The patient should be warned specifically of the possibility of malignant change associated with growth after maturity. Known lesions which cannot be palpated, should be monitored by radiography, particularly the depth of the cartilage cap. Unfortunately, bone isotope scanning cannot reliably differentiate benign from malignant cartilage lesions.41 MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) may be a reasonable alternative.

Chondroblastoma

This is a rare bone tumour usually located in the epiphyseal plate. It is essentially benign. Jaffe and Lichtenstein42 consider that it is a tumour developed from cartilaginous germ cells, although Higaki et al43 consider the cell of origin to be histiocytic. Typically, the patient is in the second decade of life and is more likely to be male. A long prodromal history is typical and there may be muscle wastage and joint restriction.44 The most common site of affliction is the upper humeral epiphyseal plate, although they can be associated with any primary or secondary site of ossification.

Typically, the lesion is radiolucent crossing the growth plate – intralesional calcification can be seen particularly with tomography.45 CT may better illustrate the local invasive properties of the tumour. It is well recognized that chondroblastoma may exhibit metastatic implantation to the pulmonary tissues. These areas if resected have a ‘benign’ histological appearance, and, therefore, represent implantation of benign tumour transported via the haematogenous route, rather than true metastases (Fig. 49.6).

Treatment of the local lesion is by a combination of curettage and excision of any adjacent soft tissue extension. The recurrence rate is approximately 20% but this may be further reduced by use of cryotherapy.46 The application of autologous bone graft will lessen the recurrence rate but conversely makes local recurrence more difficult to detect by plain radiography.

Chondromyxoid fibroma

This is a tumour which arises commonly in the upper tibia. It is most common in the second decade of life but may occur at any stage. There is often a long prodromal history, which may be as long as 2 years.47 With the exception of the clavicle, any bone may be involved, but it is much more common in the lower limb.

The radiological features are of an eccentric lesion in the metaphyseal area of a long bone. It is well defined but surrounding subperiosteal reaction may be slight.48 As with a chondroblastoma, treatment consists of an initial curettage. The recurrence rate can be reduced if the operation is supplemented with autograft.49

Malignant

Chondrosarcoma

Although chondrosarcoma may occur in the young, they predominate after the third decade of life. Both sexes are equally affected. Most patients complain of pain, however, it is well recognized that a presenting mass may be painless.50 The anatomical distribution favours the axial skeleton but 10% of tumours occur in the humerus.

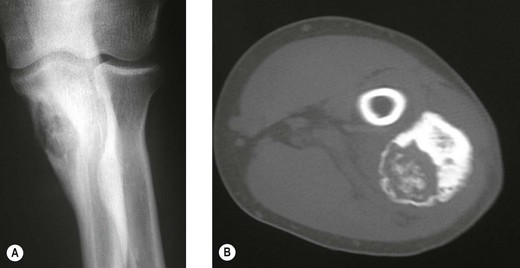

Classically the radiological appearance is of a thick-walled radiolucency with irregular blotchy areas of calcification. On the medullary surfaces the cortex is scalloped and cortical penetration occurs late in the disease. It is frequently difficult to discern radiographically the presence of a pre-existing benign tumour (Fig. 49.7).

The only treatment which is effective with chondrosarcomas is surgery, the adequacy of which is important in determining the outcome.51 The survival rate is also influenced by the degree of malignancy and site. Patients with pelvic lesions do far worse than those with upper limb tumours.50 Although most lesions require excision, preferably of a wide or radical nature, small corticated low-grade lesions in the elderly may be best served by curettage and adjuvant therapy consisting of cryosurgery, phenolization or ‘cement’ application.

Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma

This rare tumour was first described by Dahlin and Bebout in 1971. Additional mesenchymal elements are present as well as the chondrosarcoma.52 The humerus is the second commonest site. The radiological appearance may give a clue to the probability of this lesion, which may present as a purely lytic expansile area within an otherwise typical chondrosarcoma. The overall poor prognosis of patients with this tumour has led to attempts with the use of chemotherapy as a neoadjuvant therapy in addition to surgery. The lesion tends to occur in the elderly population.

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma

This is a further subtype of chondrosarcoma which rarely affects the upper limb. It is characterized by a highly cellular primitive spindle cell stroma with focal chondroid differentiation.53 The tumour occurs most frequently in the second decade of life.

Clear cell chondrosarcoma

This is an extremely rare tumour which is rather slow-growing, patients often having symptoms for up to 3 years. The most common site is the upper femur but the upper limb may be affected.54 The tumour usually appears as an osteolytic expansile lesion, usually at the proximal end of long bones. Treatment consists of complete surgical excision with reconstruction.

Tumours of histiocytic or fibrohistiocytic origin

Benign

Giant cell tumour

This is a locally aggressive but essentially benign bone tumour. It accounts for 5% of all primary bone tumours and afflicts the mature skeleton. There is a slight female predominance.55 Although commonly affecting the knee, distal radius and proximal humerus, the elbow region may be affected. Indeed patients with multiple sites have been recorded.56 All patients suspected of presenting with a giant cell tumour should have hyperparathyroidism excluded by biochemical testing.

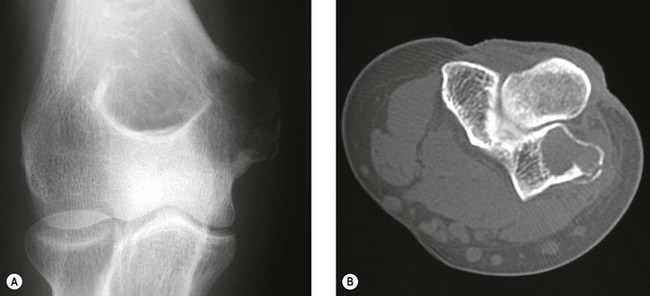

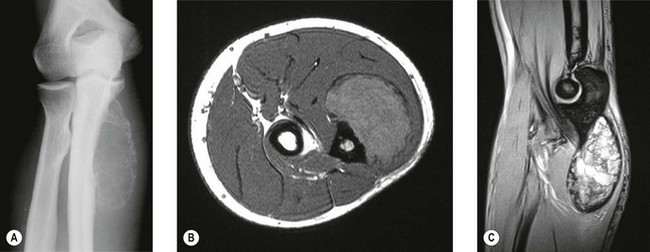

Early lesions present radiographically as expanding lytic lesions, eccentric to the long axis, often with fine trabeculae present. Most people consider that the tumour arises in the epiphysis (subarticular region) and extends to involve the metaphysis. Large lesions progress to cortical destruction and joint dysfunction (Fig. 49.8).

Figure 49.8 (A) Anteroposterior X-ray and (B) T2-weighted image of giant cell tumour of the distal humerus.

On the basis of the radiological appearance, four subtypes have been proposed which redefine the previously proposed classifications of latent, active and aggressive.57 Unfortunately, grade I probably represents benign fibrous histiocytoma and the other grades do not necessarily predict their clinical behaviour. The picture is further complicated by the histological pattern of the tumour. The osteoclasts which are present are now considered markers of the true tumour which is represented by the stromal background. This background can vary from being inconspicuous to frankly malignant and thus can profoundly affect treatment intentions.

Another poorly understood phenomenon in these tumours is the likelihood of malignant transformation of a benign tumour either following multiple local recurrences or irradiation treatment.58,59 It is important to establish whether there has been true malignant transformation of the giant cell tumour or sarcomatous induction by the radiotherapy when this modality of treatment has been used.

Primary de novo malignant giant cell tumour is a rare but well-recognized entity. Care is required, however, particularly in its differentiation from an osteoclast-rich osteosarcoma.60 When diagnosed, their treatment is as for a malignant fibrous tumour.

Given the multiplicity of combinations of local extent and histological appearance, it is difficult to be dogmatic regarding treatment. It is well recognized that curettage alone has a 20% or greater local recurrence rate.61 Recent work by the European Musculoskeletal Oncology Society in a multicentre study (unpublished), suggests that this might be halved if adjuvant therapy (phenolization, cryotherapy or polymethyl methacrylate insertion) is used in combination with intralesional techniques.

Curettage remains the mainstay of treatment, although occasionally multiple attempts may be required. Reconstruction may not always be required after curettage and a number of patients have been treated by simple casting or cast bracing alone until in-filling of the cavity occurs.62 If articular failure has occurred by fracture or tumour invasion, then reconstruction with a prosthesis or allograft will be required.

Non-ossifying fibroma/benign fibrous histiocytoma

Non-ossifying fibroma is the general term given to a lesion which is larger than a fibrous cortical defect. The term metaphyseal fibrous defect may be used for both. These lesions are extremely common between the ages of 4 and 8 years and can affect any metaphysis. They are rarely seen in adults, which probably reflects the natural history of the condition. Large lesions may be associated with pathological fractures.63

Radiological features are characteristic consisting of an eccentric lesion which may involve the cortex situated at the end of the diaphysis. A sclerotic rim is usually seen on the medullary border. Although the lesion does not usually require biopsy, unusual clinical or radiological features may justify the need for needle biopsy. Treatment in the majority of cases is only observation. Enlargement or pathological fracture will demand curettage or block excision with or without bone grafting. Fractures occasionally lead to obliteration of the lesion.64

Malignant

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

This is a rare tumour which tends to affect the diaphysis of the appendicular skeleton. It is a tumour which must be differentiated from the dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma, fibroblastic osteosarcoma and fibrosarcoma. In all, 70% of tumours arise de novo, the remaining 30% arising in bones with infarction, irradiation, Paget’s disease and fibrous dysplasia.65

The radiological features are usually an area of poorly delineated osteolysis without other characteristic features. Pathological fracture is a common occurrence. Where the lesion arises secondarily to a pre-existing condition then this pathology may be visible. Endosteal scalloping, periosteal reaction or a soft tissue mass are indicative of malignant transformation.66

Treatment of malignant fibrous histiocytoma is now very much along the lines of that for osteosarcoma. The fact that this lesion will respond to chemotherapy has been noted for some time,67 although since the patients are older (the mean age being around 40 years) this mode of therapy is less well tolerated. Following neoadjuvant chemotherapy, any surgical treatment is by wide excision which around the elbow consists of prosthetic replacement of the distal humerus and proximal ulna.

Ewing’s sarcoma

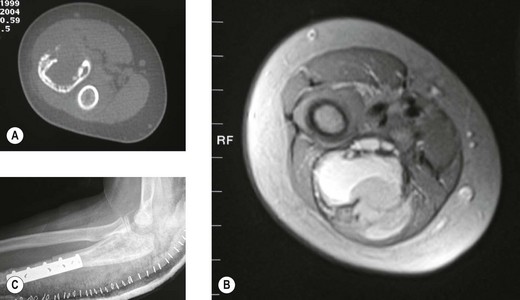

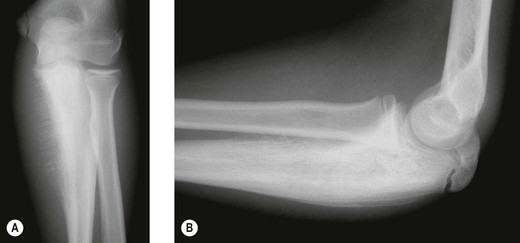

The classical description of the radiological appearance is a moth-eaten medullary bone with periosteal lamination of new bone. Repeated events of lamination will lead to the classical so-called onion-skin appearance. This appearance is, however, rare and is not pathognomic.68 More frequently, patchy lysis and sclerosis are seen (Fig. 49.9). Staging investigations are particularly important in this condition as with their increasing use and sophistication a greater percentage of patients are found to have either multifocal bone disease of pulmonary metastases. These findings have a detrimental effect on overall survival. Local staging is also important to decide whether a surgical approach is feasible (Fig. 49.10A,B).

Figure 49.9 (A) Anteroposterior and (B) lateral X-rays of Ewing’s sarcoma of the proximal ulna in a growing child.

Biopsy material requires extremely careful evaluation and scrutiny. Immunohistochemical techniques will be required to differentiate the lesion from PNET, neuroblastoma, small-cell osteosarcoma, lymphoma of bone and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Having established a diagnosis, the optimal mode of treatment is still unclear. Chemotherapy certainly has a role to play and its usage has increased with overall 5-year survival varying from 20% to 50%.69 The difficulty remains in that there are a number of variables which are recognized to affect survival rates. Among these are age and sex of a patient, site of lesion and its measurable volume.70

Although the role of chemotherapy is not in dispute, the management of the local primary lesion is still controversial. The traditional local therapy is radiation, although the local recurrence rate with this mode of treatment is probably around 30%. Surgery can do better, but the results are liable to bias as this modality is often chosen to treat distally situated lesions (Fig. 49.10C). Finally, irradiation may also lead to the induction of post-irradiation sarcomas.71

Simple bone cyst (unicameral bone cyst)

These fluid-filled cysts often arise in the metaphyseal region of long bones juxtaposed to the epiphyseal plate. They are usually brought to the patient’s attention either by an incidental X-ray or following a pathological fracture. Fracture may lead to resolution of the cyst, however, it is also well recognized that a traumatic episode may turn a cystic lesion into an aneurysmal bone cyst.72

Plain X-rays usually show a lesion which has a central medullary location. Its length is usually greater than its width. The transverse diameter of the cyst closest to the epiphysis is recognized as being as wide as the epiphysis. With age, the cyst grows towards the diaphysis. This appearance is contrary to an aneurysmal bone cyst, which shows a centrifugal growth pattern. When the cyst abuts on cancellous bone there is a reaction, although a periosteal reaction is rare. There is no soft tissue component. Further radiological investigation is rarely performed, although it is possible to recognize fluid levels on CT scanning. Treatment can be difficult. Small cysts which are asymptomatic do not require any therapy. However, large cysts may require curettage, bone grafting, en bloc resection or even nailing. It is now accepted that these cysts will respond to an injection of methylprednisolone.73 If surgery is contemplated, incomplete removal of the cyst lining usually leads to local recurrence. The recurrence rate is much higher in children.74

Aneurysmal bone cyst

This is predominantly a disease of the first three decades of life and occurs equally in both sexes. It can affect any bone and 8% are recorded as occurring in the upper limb. The radiological features are of a purely lytic expansile lesion which usually arises in the metaphysis. Extensions may occur into the epiphysis when the growth plate has closed.75 These may grow alarmingly rapidly mimicking malignant tumours (Fig. 49.11). If further radiological investigation is required, the multiple fluid levels seen on CT are practically diagnostic of an aneurysmal bone cyst.

The mainstay of treatment is a combination of curettage and bone grafting. Where the tumour arises in inaccessible sites or where major blood loss is feared, arterial embolization may be a helpful adjunct to treatment. In tumours that recur or remain inaccessible, small doses of radiation can be given.76

Soft tissue sarcomas

Interpretation of the histopathology of soft tissue sarcomas is extremely difficult. Enzinger and Weiss77 have recognized over 200 subtypes which makes guidance on treatment and outcome extremely difficult. Techniques involving immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics have recently been introduced and are helpful in classifying tumours, however, whether they have any prognostic value remains debatable.

The adequate surgical removal of a sarcoma still remains the mainstay of treatment. Inadequate surgery has a very high rate of recurrence. This was described by Enneking.78

Radical resection

Radiotherapy plays an important role in limb-salvage procedures. High-dose radiation can sterilize small foci of residual tumour after marginal resection and it should always be considered after resection of high-grade malignant tumours. It is important that any decision regarding radiotherapy is part of a multidisciplinary team. The technique of brachytherapy can be used in selected cases to minimize damage to surrounding healthy tissue and reduce post-irradiation contracture and joint destruction.79

Miscellaneous tumours of soft tissue

Myositis ossificans

Radiographic features show no abnormality in the first 2–3 weeks and then speckled calcification becomes evident. A fully mature lesion can usually be seen at around 14 weeks. In general, the diagnosis should be made on clinical and radiological grounds as great care is required with the examination of a biopsy. Unfortunately, myositis ossificans can be easily mistaken for osteogenic sarcoma.80

Surgical techniques and rehabilitation

Where the lesion is contained within the bone (Enneking stage 11A) or is contained beneath the expanded periosteum (stage 11B) and gives clinical and radiographic indication of responding to chemotherapy, then a wide local excision of the lesion may be justified. Where the lesion is of low-grade malignancy (stage 1A or 1B) this type of conservative approach will lead to good local control.81

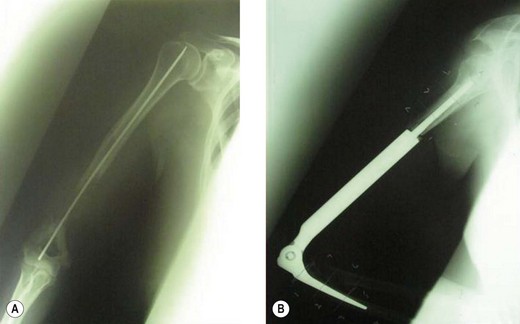

In benign disease such a radical approach is rarely justified unless other methods aimed at maintaining joint integrity have failed. Following wide excision of the elbow joint, reconstruction can be achieved by a number of difference approaches. None is ideal and some are inapplicable if an extra-articular resection of the joint has been performed. Enneking82 reported a method of arthrodesis, although this is often difficult to achieve. In smaller resections, hemiarthroplasty of the distal humerus or proximal ulna may be appropriate.83–87 In the USA, Mankin has popularized the use of cadaveric allografts and, although function in the upper limb is better than in the lower limb, there are still problems of sizing, stability, fracture, rejection and degeneration.88,89

In Europe and Japan, prosthetic reconstructions replacing the total elbow have been developed.90 The results in 26 patients have been reported, with a local recurrence rate and loosening rates of 11.5% but no prosthetic failures. Since the publication of this paper, two important developments have led to a reduction in this complication rate. First, better staging procedures, particularly MRI, have led to more accurate visualization of the tumours and, therefore, better selection for limb salvage surgery. Second, the rate of aseptic loosening has been reduced by the development of a ‘flexi-elbow’ or ‘sloppy hinge’ design instead of the earlier constrained variety (Fig. 49.12).

The results of customized elbow replacements in malignant disease have recently been reviewed by Lambert et al.91 When assessed by a Mankin functional grading system, 80% of patients were good or excellent. Only one patient reviewed had instability of his prosthetic hinged mechanism. If a second score – the Mayo elbow performance index – is used, the average gain in function is 16.25 points, which is largely due to pain relief achieved by the operation. Radiological evaluation remains good.

1 Cooper A. Exostosis. In: Cooper A, Travers B, editors. Surgical Essays. 3rd edn. London: Cox & Son; 1818:169-226.

2 Huvos AG, editor. Bone Tumours. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1991:225.

3 Solomon L. Bone growth in diaphyseal aclasis. J Bone Joint Surgery (Br). 1961;43:700-716.

4 Ollier M. Dyschondroplasie. Lyon Med. 1900;93:23-25.

5 Maffucci A. Di un caso di enchondroma ed angiome multiplo. Mov Med Chir. 1991;13:399-412.

6 Elmore SM, Cantrell WC. Maffucci’s syndrome – case report with a normal karyotype. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1966;48:1607-1613.

7 Nelaton E. D’une nouvelle espéce de tumeurs benignes des os, ou tumours a myeloplaxes. Paris: Adrien Delahayle; 1860.

8 Paget J. Lectures in surgical pathology. Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blackiston; 1854.

9 Ewing J. Diffuse endothelioma of bone. Proc NY Path Soc. 1921;21:17-24.

10 Ewing J. A review and classification of bone sarcomas. Arch Surg. 1922;4:483-533.

11 Lucke A. Beitrage zur Geschwulstlehre Virehars Arch. Patholog Anat. 1866;35:524-539.

12 Saville PD. A medical option for the treatment of osteoid osteoma. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:1409-1411.

13 Leonessa C, Savoni E. Osteoma osteoide para articulare del gomito. Chir Organic Mov. 1971;59:487-492.

14 Marcove RC, Freiberger RH. Osteoid osteoma of the elbow – a diagnostic problem. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1966;48:1185-1190.

15 Shifrin LZ, Reynolds WA. Intra-articular osteoid osteoma of the elbow. Clin Orthop. 1971;81:126-129.

16 Sim FH, Dahlin DC, Beabout JW. Osteoid osteoma – diagnostic problems. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1975;57:154-159.

17 Gamba JL, Martinez S, Apple J, et al. Computed tomography of axial skeletal osteoid osteoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142:769-772.

18 Szypryt EP, Hardy JG, Colton CL. An improved technique of intra-operative bone scanning. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1986;68:643-646.

19 Taminiau A, Berg de JC, Oberman WR. Percutaneous computer tomography-guided thermocoagulation for osteoid osteomas. Trans Int Soc Limb Salvage. 1977:159.

20 Hoffman RT, Jakobs TF, Kubisch CH, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of osteoid osteoma. A five year experience. Eur J Radiol. 2009;7:23.

21 Lepage J, Rigault P, Nezeloft C, et al. Benign osteoblastoma in children. Rev Clin Orthop. 1984;70:117-127.

22 Camepa GM, Defabiani F. Osteoblastoma del radio. Minerva Orthop. 1965;16:645-648.

23 Williams G, Barrett G, Pratt C. Osteosarcoma in two very young children. Clin Paediatr. 1977;16:548-551.

24 Price CHG. Primary bone-forming tumours and their relationship to skeletal growth. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1958;40:574-593.

25 Simmons CC. Bone sarcoma: factors influencing prognosis. Surg Gynaecol Obstet. 1939;68:67-75.

26 Mankin HJ, Connor JF, Schiller AC, et al. Grading of bone tumours by analysis of nucleus DNA content using flow cytometry. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1985;67:404-413.

27 Coffre E, Vanel D, Contesso G, et al. Problems and pitfalls in the use of computed tomography for the local evaluation of long bone osteosarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 1985;13:147-153.

28 Flowers JMJr. 99m Tc-polyphosphate uptake within pulmonary and soft tissue metastases from osteosarcoma. Radiology. 1974;112:377-378.

29 Stoker DJ, Cobb JP, Pringle JAS. Needle biopsy of musculoskeletal lesions. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1991;73:498-500.

30 Cade S. Sarcoma of bone. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1951;9:211-223.

31 Beck JC, Wara WM, Bovill EGJr, et al. The role of radiation therapy in the treatment of osteosarcoma. Radiology. 1976;120:163-165.

32 Rosen G, Tan C, Exelby P. Vincristine, high-dose Methotrexate with cirtovarum factor rescue, cyclophosphamide and Adriamycin cyclic therapy following surgery in childhood osteogenic sarcoma. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 1974;15:172.

33 Whelan J, Seddon B, Perisoglou M. Management of osteosarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2006;6:444-455.

34 Geschickter CF, Copeland MM. Parosteal osteosarcoma of bone: a new entity. Ann Surg. 1951;133:790-807.

35 Campnacci M, Picci P, Gherlinzoni F, et al. Parosteal osteosarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1984;66:313-321.

36 Wold LE, Unni KK, Beabout JW, et al. Dedifferentiated parosteal osteosarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1974;66:53-59.

37 Hall FM. Periosteal sarcoma. Radiology. 1978;129:835-836.

38 Campanacci M, Giunti A. Periosteal osteosarcoma – review of 41 cases. Ital J Orthop Trauma. 1976;2:23-35.

39 Tomsu M, Procek J, Wagner K, et al. Vascular complications in osteochondromatosis. Rozhl Chir. 1977;56:696-699.

40 Fogel G, McElfresh EC, Peterson HA, et al. Management of deformities of the forearm in multiple heredity osteochondromas. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1984;66:670-680.

41 Hudson TM, Chew FS, Manaster BJ. Scintigraphy of benign exostoses and exostotic chondrosarcomas. Am J Radiol. 1983;140:581-586.

42 Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein C. Benign chondroblastoma of bone. Am J Pathol. 1942;18:969-983.

43 Higaki S, Takeyama S, Tateishi A. Clinical pathological study of twenty-two cases of benign chondroblastoma. Nippon Seikeigeha Gahhai Zasshi. 1981;55:647-664.

44 Bloem JL, Mulder JD. Chondroblastoma: a clinical and radiological study of 104 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8:223-230.

45 Hudson TM, Hawkins IFJr. Radiological evaluation of chondroblastoma. Radiology. 1981;139:1-10.

46 Huvos AG, Marcove RC. Chondroblastoma of bone – a critical review. Clin Orthop. 1973;95:300-312.

47 Rahimi A, Beabour JW, Ivins JC, et al. Chondromyxoid fibroma – a clinical pathological study of 76 cases. Cancer. 1972;30:726-736.

48 Schajowicz F. Chondromyxoid fibroma – a report of three cases with predominant cortical involvement. Radiology. 1987;164:783-786.

49 Gerlinzoni F, Rock M, Picci P. Chondromyxoid fibroma. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1983;65:198-204.

50 Marcove RC, Mike V, Hutter RVP, et al. Chondrosarcoma of the pelvis and upper end of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1972;54:561-572.

51 Kaufman JH, Douglass HOJr, Blake W, et al. The importance of initial presentation and treatment upon the survival of patients with chondrosarcoma. Surg Gynaecol Obstet. 1977;145:357-363.

52 Dahlin DC, Beaumont JW. Dedifferentiation of low grade chondrosarcoma. Cancer. 1971;28:461-466.

53 Lichtenstein L, Bernstein D. Unusual benign and malignant chondroid tumours of bone. Cancer. 1959;12:1142-1157.

54 Bjornsson J, Unni KK, Dahlin DC, et al. Clear cell chondrosarcoma of bone – observations in 47 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8:223-230.

55 Hutter RVP, Worcester JNJr, Francis KC, et al. Benign and malignant giant cell tumours of bone. Cancer. 1962;15:653-690.

56 Singson R, Feldman F. Case report 229: diagnosis of multiple (multicentric) giant cell tumours of bone. Skeletal Radiol. 1983;9:276-281.

57 Campanacci M, Baldini N, Boriani S, et al. Giant cell tumour of bone. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1987;69:106-114.

58 Hadders HN. Some remarks on the histology of bone tumours. Year Book Cancer Res Amsterdam. 1973;22:7-10.

59 Tudway RC. Giant cell tumour of bone. Br J Radiol. 1959;32:315-321.

60 Nascimento AG, Huvos AG, Marvoe RC. Primary malignant giant cell tumour of bone. Cancer. 1979;44:1393-1402.

61 Johnson EWJr. Adjacent and distal spread of giant cell tumours. Am J Surg. 1965;109:163-166.

62 Kemp HBS, Cannon SR, Briggs TWR, et al. Shark-bite: a conservative method for the treatment of cysts, benign tumours and selected malignant tumours of bone. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1996;78(Suppl. 1):58.

63 Arata MA, Peterson HA, Dahlin DC. Pathological fractures through non-ossifying fibromas. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1981;63:980-988.

64 Cunningham JB, Ackerman LV. Metaphyseal fibrous defects. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1956;38:797-808.

65 Huvos AG, Heilwell M, Bretsky SS. The pathology of malignant fibrous histiocytoma of bone. Am J Pathol. 1985;9:853-871.

66 Taconis WK, Mulder JD. Fibrosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma of long bone: radiographic features and grading. Skeletal Radiol. 1984;11:237-245.

67 Bacci G, Springfield D, Capanna P, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the femur and tibia. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1985;67:620-625.

68 Feldman F. Round cell lesions of bone. In: Potchen EJ, editor. Diagnostic Radiology. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1977:437-454.

69 Rosen G. The current management of malignant bone tumours. Med J Aust. 1988;148:373-378.

70 Gobel V, Jurghens H, Etspuler G, et al. Prognostic significance of tumour volume in localised Ewing’s sarcoma of bone in children and adolescents. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1987;113:187-191.

71 Juergens C, Wesron C, Lewis I, et al. Safety assessment of intensive induction with vide in the treatment of Ewing’s tumours – Euro-Ewing. Paediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47:22-29.

72 Johnston CE, Fletcher RR. Traumatic transformation of unicameral bone cyst into aneurysmal bone cyst. Orthopaedics. 1986;9:1441-1477.

73 Campanacii M, Capanna R, Picci P. Unicameral and aneurysmal bone cysts. Clin Orthop. 1986;204:35-36.

74 Norman A, Schiffman M. Simple bone cysts: factors of age dependency. Radiology. 1977;124:779-782.

75 Dyer R, Stellilng CB, Fechner RE. Epiphyseal extension of an aneurysmal bone cyst. Am J Radiol. 1981;137:153-168.

76 Biesecker JL, Marcove RC, Huvos AG, et al. Aneurysmal bone cysts. A clinico-pathological study of 66 cases. Cancer. 1970;26:615-625.

77 Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Soft Tissue Tumours, 3rd edn. St Louis: Mosby; 1995.

78 Enneking WF. Staging of Musculoskeletal Neoplasms. Current Concepts of Diagnosis and Treatment of Bone and Soft Tissue Tumours. New York: Springer Verlag; 1986.

79 Hilaris BS, Bodner WR, Mastorias CA. The role of brachytherapy in adult soft tissue sarcomas. Semin Surg Oncol. 1997;13:196-203.

80 Ackerman L, Ramamurthy S, Jablokow V, et al. Case report 488: Post traumatic myositis ossificans mimicking a soft tissue neoplasm. Skeletal Radiol. 1988;17:310-314.

81 Enneking WF, Spanier SS, Goodman MA. A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcoma. Clin Orthop. 1980;153:106-120.

82 Enneking WF. Musculoskeletal tumour surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1983.

83 Mellen RH, Phalen GS. Arthroplasty of the elbow by replacement of the distal portion of the humerus with an acrylic prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1947;29:348-353.

84 Barr JS, Eaton RG. Elbow reconstruction with a new prosthesis to replace the distal end of the humerus: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1965;47:1408-1413.

85 Kestler OC. Replacement of the distal humerus for reconstruction of the elbow joint: report of two cases with long follow up. Bull Hosp Joint Dis. 1970;31:85-90.

86 Dunn AW. A distal humeral prosthesis. Clin Orthop. 1971;77:199-202.

87 Johnson EWJr, Schlein AP. Vitallium prosthesis for the olecranon and proximal part of the ulna: case report with thirteen year follow up. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1970;52:721-724.

88 Mankin JH, Dopperts S, Tomford W. Clinical experience with allograft implantation: the first ten years. Clin Orthop. 1983;174:69-86.

89 Urbaniak JR, Black KEJr. Cadaveric elbow allografts: a six year experience. Clin Orthop. 1985;197:131-140.

90 Ross AC, Sneth RS, Scales JT. Endoprosthetic replacement of the humerus and elbow joint. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1987;69:652-655.

91 Lambert S, Davis J, Cannon SR. Endoprosthetic reconstruction for tumours of the elbow region. Trans Int Soc Limb Salvage. 1995:96.