classification, grading and staging

Tumours exhibit a wide variety of behaviour and have a myriad of possible effects. Pathological analysis of neoplasms aims to allow sensible correlation with aetiological factors, to help select the best treatment, and to predict the prognosis. This is done by:

• classifying neoplasms according to the type of normal tissue they resemble

• grading them according to how closely they resemble normal tissue

• staging them by how far they have spread through the body.

12.1. Pathological characteristics of neoplasms

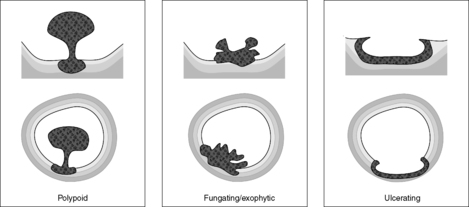

Macroscopic (naked eye) examination gives a preliminary idea of the nature of the tumour, since the growth pattern depends on the site of origin, speed of growth and cellular characteristics. Polypoid neoplasms stand above the adjacent tissue surface; exophytic neoplasms also do so but in an irregular way; fungating neoplasms are large, exophytic tumours with necrosis and surface ulceration; while the term ulcerating is used for ulcerated neoplasms that grow into the underlying tissue without a large exophytic component (Figure 30).

|

| Figure 30 |

Some clues as to whether the tumour is benign or malignant may be obtained by macroscopic examination. Infiltration of surrounding tissues implies malignancy, while a well-circumscribed tumour surrounded by a capsule of reactive fibrous tissue is more likely to be benign. Neoplasms with extensive necrosis or a fungating appearance are probably malignant.

The mainstay of routine pathological classification is still light microscopy using sections stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Sometimes, special stains, immunohistochemistry or molecular techniques (see Ch. 2) may be needed for accurate classification. In some tumours, characteristics such as hormone receptor expression may give additional information about how the tumour is likely to respond to treatment.

Tumour markers

Some tumours secrete substances which can be detected in the blood or urine (Table 17). They may be:

• substances normally produced by the tissue but in excessive amounts, e.g. PSA produced by prostatic carcinoma

• substances not normally produced by the tissue (ectopic production), e.g. adrenocorticotrophic hormone from a lung cancer

• substances usually only seen in primitive or fetal tissues, such as CEA and AFP.

| Marker | Tumour |

|---|---|

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) | Colorectal disease, benign and malignant |

| Human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) | Malignant teratoma |

| Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) | Malignant teratoma, hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Prostatic specific antigen (PSA) | Prostate cancer |

| Vanillyl mandelic acid (VMA) | Neuroblastoma |

| 5-Hydroxy indole acetic acid (5HIAA) | Carcinoid tumour |

Tumour markers are used clinically in the initial diagnosis of a neoplasm and in monitoring its response to treatment. For example, detecting markedly raised PSA in the blood of a man with prostatic symptoms suggests prostatic carcinoma. After surgical resection of the cancer, the level of PSA should return to normal, but if it starts to rise again, it suggests recurrence of the cancer.

Prognostic factors in neoplasia

Many factors affect the prognosis of a patient with a neoplasm. It is useful conceptually to divide them into three groups:

• tumour-related factors

• host-related factors

• access to care.

Tumour-related factors

Host-related factors

These are characteristics of the patient. For example, other diseases, called co-morbidities in this context, may worsen the patient’s overall condition, or prevent optimum therapy (e.g. respiratory disease may prevent an anaesthetic for surgical resection). The very old and very young sometimes have a worse prognosis than the rest of the population.

Access to care

The available treatment may be important in prognosis, i.e. whether optimum care is available and whether the individual has access to that care. These are sometimes called ‘environment-related factors’.

12.2. Classification of neoplasms

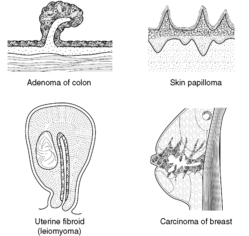

Neoplasms are named according to whether they are benign or malignant (see Ch. 11) and by the type of tissue they resemble. In general, although there are important exceptions, benign neoplasms have the suffix -oma, malignant neoplasms arising from epithelial tissues are called carcinomas and malignant neoplasms arising from mesenchymal tissue are called sarcomas (Table 18, Figure 31). The rest of the name usually indicates the type of tissue the neoplasm resembles. Thus, adenoma means ‘benign neoplasm of glandular epithelium’, adenocarcinoma means ‘malignant neoplasm of glandular epithelium’, and chondrosarcoma means ‘malignant neoplasm of cartilage’.

| Tissue of origin | Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|---|

| Squamous epithelium | Squamous papilloma | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Glandular epithelium | Adenoma | Adenocarcinoma |

| Smooth muscle | Leiomyoma | Leiomyosarcoma |

| Fat | Lipoma | Liposarcoma |

| Bone | Osteoma | Osteosarcoma |

| Skeletal muscle | Rhabdomyoma | Rhabdomyosarcoma |

Unfortunately, there are exceptions to these rules. For example,

• melanoma and lymphoma are malignant despite the fact they end with -oma

• some neoplasms cannot be easily classified as benign or malignant; some are given names such as ‘borderline tumour’.

Hamartomas (Box 16) are not generally considered to be neoplastic because they stop growing when the individual reaches adulthood. However, they may have genetic abnormalities similar to true neoplasms.

Box 16

Hamartomas are tumour-like masses of tissue but are not classified as neoplastic. They are composed of a mixture of tissues normally found at the site and grow slowly with the host. For example, hamartomatous polyps of the bowel consist of smooth muscle, glandular elements and blood vessels. Bronchial hamartomas contain cartilage, smooth muscle and bronchial epithelium.

Usually – though not always – tumours tend to resemble the tissue in which they arise. For example, squamous cell carcinomas are commonest in squamous epithelia (including metaplastic squamous epithelia).

12.3. Grading and staging

Grade and stage are two important features of a tumour that are commonly associated with prognosis and response to treatment.

Grade

The grade of a neoplasm describes how closely the tumour resembles normal tissue, i.e. the degree of cellular differentiation. A tumour that closely resembles its normal counterpart is called well differentiated or low grade, whereas a tumour that shows little resemblance to normal is called high grade or poorly differentiated. Moderately differentiated is a term for an intermediate degree of differentiation.

In some tumours, there are established numbered grading systems, usually of three of four groups, with grade 1 representing the most well differentiated neoplasms and grade 3 or 4 representing the least degree of differentiation. For example, breast carcinomas are divided into three grades based on the degree of tubular differentiation, nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic count. Renal cell carcinomas are divided into four grades based on nuclear characteristics such as size and shape.

The significance of grade is that it can be related to prognosis and response to treatment. High-grade neoplasms tend to grow faster and spread more rapidly than low-grade lesions. For example, in the case of large intestinal adenocarcinomas, well differentiated and moderately differentiated lesions have a better prognosis than poorly differentiated ones.

Stage

The stage of a neoplasm is determined by how far it has spread at the time of diagnosis. The concept only applies to malignant neoplasms, since benign tumours do not spread. In most cancers, it is the single most important tumour-related prognostic feature. Generally, the earlier a cancer is detected and treated, the better the outlook for the patient.

In the TNM system of tumour staging, a score is given for the extent of local spread (T category), local lymph node involvement (N category) and distant metastases (M category). These scores can then be used to calculate the stage group of the tumour. Each cancer has its own particular scoring system, but in general the higher the number the further the cancer has spread.

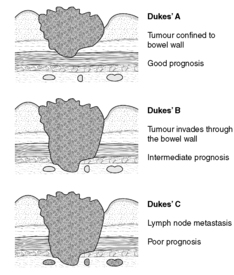

In the case of large intestinal carcinomas, another commonly used staging system is the Dukes’ classification (Figure 32).

|

| Figure 32 |

Self-assessment: questions

One best answer questions

2. Which one of the following is most likely to suggest a lymphoma?

a. atypical lymphocytes in a lymph node aspirate

b. papillary lesion of the oesophagus

c. raised serum carcinoembryonic antigen

d. reduced serum calcium

e. reduced numbers of circulating lymphocytes

3. Which one of the following features is likely to suggest a neoplasm is benign?

a. enlarged regional nodes

b. extensive necrosis of the tumour

c. growth of the tumour along nerves

d. fungating appearance

e. smooth external borders of the tumour

Extended matching items questions (EMIs)

EMI 1

Theme: Classification of neoplasms

A. adenocarcinoma

B. adenoma

C. chondroma

D. chondrosarcoma

E. hamartoma

F. leiomyoma

G. leiomyosarcoma

H. lymphoma

I. osteoma

J. osteosarcoma

K. teratoma

For each of the following questions, select the most appropriate response from the above list. Each response may be used once, more than once, or not at all.

1. A pathologist examines a tumour under the microscope and sees malignant glandular epithelium. What is the most appropriate classification?

2. Which name should be given to malignant tumour of smooth muscle?

3. tumour has arisen in the epithelium of the stomach and spread to regional lymph nodes. Which is the most likely tumour type?

4. Which lesion is not neoplastic?

5. A gynaecologist removes an ovarian tumour. He sees that it contains a mixture of tissues, including hair, teeth-like structures, bone and fat. What is the most likely diagnosis?

Case history questions

Case history 1

A 53-year-old woman presented to her doctor with a lump in her breast. On examination, the lump was in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast and was fixed to the skin which was puckered over the surface. The nipple was slightly inverted. The lump felt hard and craggy to palpation and was approximately 4cm in diameter. The GP felt several enlarged lymph nodes in the axilla on the same side. The patient admitted that the lump had been present for at least a year, but she had been too scared to see her doctor before.

The GP referred her urgently to a breast surgeon. Fine needle aspiration with examination of the cells removed showed that the tumour was malignant and surgery was performed (lumpectomy with axillary node clearance). The pathologist reported that the tumour was a malignant carcinoma of ductal origin which had been completely excised. The lymph nodes contained metastatic tumour.

Several months later the patient presented with pain in the femur and a pathological fracture.

1. Why was the lump fixed to the skin?

2. How does breast cancer spread?

3. How might breast screening have altered the course of the disease in this patient?

4. What is the significance of the bone pain and fracture?

Self-assessment: answers

One best answer

2. a. The presence of atypical (i.e. cytologically abnormal) lymphocytes is highly suggestive of a neoplastic proliferation. An oesophageal papillary lesion is most likely to be a squamous cell papilloma. CEA is typically raised in intestinal tumours. In lymphomas, the numbers of circulating lymphocytes are usually normal or increased.

3. e. Tumours with smooth external borders are described as well circumscribed. Benign tumours tend to have this appearance because they are confined to their site of origin. However, there are numerous exceptions! In contrast, enlarged regional nodes suggest that nodal metastases are likely, and extensive necrosis, perineural invasion and fungating growth are usually encountered in malignancies.

EMI answers

EMI 1

Theme: Classification of neoplasms

1. A. The nature of the lesion is reflected in the name: ‘carcinoma’ means malignant epithelial neoplasm, while ‘adeno-’ indicates glandular.

2. G. ‘Leiomyo-’ means smooth muscle; ‘sarcoma’ means malignant mesenchymal tumour.

3. A. The gastric epithelium is glandular, so glandular neoplasms are most common. This tumour must be malignant because it has spread to lymph nodes. Hence, it is an adenocarcinoma.

4. E. Hamartomas are not considered neoplastic because they behave as if they respond normally to constraints on cell growth. They are composed of tissues normally found at the site.

5. K. This lesion contains elements derived from at least two germ layers, ectoderm (teeth and hair) and mesoderm (fat and bone). Therefore, it is a teratoma. Most ovarian teratomas are benign and are called dermoid cysts. However, this lesion will require careful examination under the microscope to exclude any malignant elements.

Case history answers

Case history 1

1. Tumour fixation indicates that the tumour was invading the overlying skin. This gives it a puckered appearance. Sometimes tumour cells obstruct the lymphatics of the overlying skin, resulting in oedema and pitting of the surface rather like the skin of an orange. This clinical sign is called ‘peau d’orange’ and is a bad prognostic sign.

2. Breast cancer follows the general rules of spread of all cancers. It may invade locally into adjacent structures such as the skin, nipple and pectoralis muscles. Lymphatic spread to draining lymph nodes is common, in this case to axillary lymph nodes on the same side. Eventually, haematogenous spread may occur with metastases in the bones, lung, brain, liver or elsewhere.

3. If the patient had presented earlier, there may have been a chance that the tumour had not already spread either so extensively locally or to the lymph nodes. The earlier tumours are detected, usually, the better the prognosis. Breast screening programmes are designed to detect neoplasms before they become advanced, and should reduce the death rate from breast cancer.

4. The bone pain is caused by metastatic breast carcinoma (haematogenous spread) which has invaded the femur and caused it to become weak and fracture spontaneously (pathological fracture).