106 Neonatal Resuscitation

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Fetal Circulation

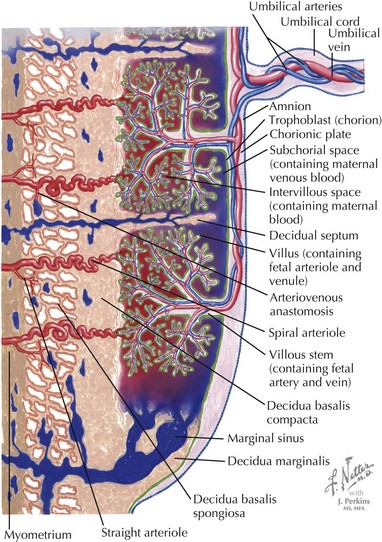

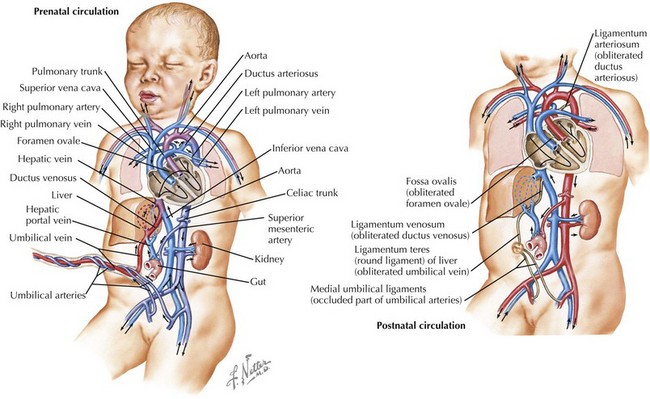

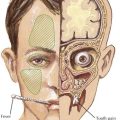

In fetuses, the placenta performs the primary gas exchange function rather than the lungs, and several circulatory adaptations exist to facilitate flow of oxygenated blood through the body and placenta. Deoxygenated blood from the body of the fetus flows to the placenta via the umbilical artery and becomes oxygenated through gas exchange with maternal blood. The oxygenated blood then flows back to the fetus via the umbilical vein (Figure 106-1). The umbilical vein deposits the blood to the inferior vena cava via the ductus venosus, which subsequently delivers it to the right atrium of the heart. In the right atrium, the blood partially mixes with blood from the superior vena cava, and the majority of it streams across the foramen ovale to the left atrium because of the high pulmonary vascular resistance. From the left atrium, blood flows through the left ventricle to the aorta, thereby delivering the most oxygenated blood to the brain via the carotid arteries. The remaining blood in the right atrium, largely from the superior vena cava, flows into the right ventricle and then into the pulmonary artery. A small amount of blood perfuses the lungs and then travels to the left atrium via the pulmonary veins. Most of the blood, however, is diverted across the ductus arteriosus to the descending aorta, where it joins the blood from the left ventricle. From the aorta, the blood is distributed via branches off the aorta and ultimately reaches the umbilical artery and the low pressure placenta again (Figure 106-2).

Transition to Neonatal Circulation

This system changes dramatically when the infant is born. Because of the stress of labor and delivery, the baby experiences a catecholamine surge at birth. Catecholamines regulate fluid resorption in the lungs, surfactant release into the alveoli, temperature, glucose mobilization, and blood flow to the brain and vital organs. When the umbilical cord is clamped, the placenta is removed from the circulation, causing a large increase in systemic vascular resistance. When the infant takes his or her first breath, the pulmonary vascular resistance decreases precipitously, causing blood to travel through the right atrium to the right ventricle and then the lungs rather than through the foramen ovale to the left atrium. The lower pulmonary pressures also result in less blood flow across the ductus arteriosus and more flow from the pulmonary artery to the lungs. The ductus venosus, ductus arteriosus, and umbilical vessels eventually constrict, leaving the infant with a fully intact neonatal circulatory system (see Figure 106-2). The initial breaths taken by the infant also must inflate the lungs and effect a change in vascular pressures so lung water is absorbed into the pulmonary arterial system and cleared from the lung.

Asphyxia

In some cases, the fetal reserve is not enough to protect the infant from difficulties with transition. Neonatal asphyxia can result from multiple factors, both maternal and fetal (Table 106-1), and may begin in utero. The initial response to asphyxia is a brief period of rapid breathing followed by “primary apnea.” During primary apnea, stimulation such as drying or slapping the feet will restart breathing. If the apnea is prolonged, the infant loses muscle tone and becomes cyanotic and then bradycardic. After a few gasping respirations, the neonate enters “secondary apnea.” At this point, ventilatory support must be provided for the newborn to survive. In this situation, an infant requires resuscitative efforts to aid in the transition to extrauterine life.

| Maternal | |

|---|---|

| Uterus | Uterine malformations, hypertonus, rupture |

| Infection | Chorioamnionitis |

| Blood | Anemia, hemoglobinopathy |

| Vascular | Diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, hypotension |

| Medications Placenta |

Narcotics, magnesium Uteroplacental insufficiency, placental abruption, placenta previa, postmature placenta |

| Fetal | |

|---|---|

| Umbilical cord | Compression, prolapse, knot, nuchal cord, thrombosis |

| Blood | Anemia |

| Other | Infection, fetal hydrops, malformations, multiple gestations, inborn error of metabolism |

Evaluation And Management

Neonatal Resuscitation Guidelines

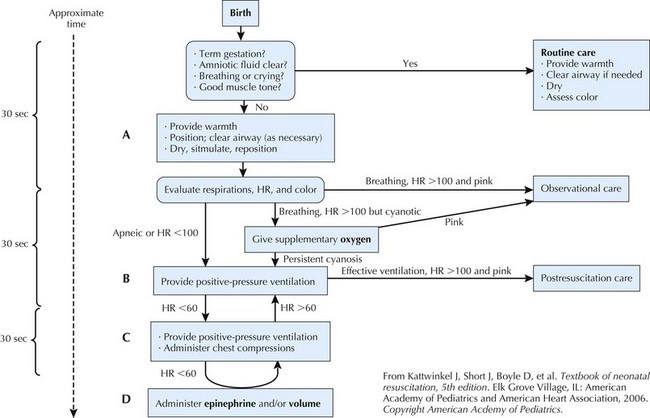

The NRP was introduced in 1987; its goal is to ensure that a health care professional trained in providing care to newborns just after delivery is present at every birth in the United States. To accomplish this goal, the NRP has compiled an algorithm standardizing neonatal resuscitation techniques, which was last revised in 2005 (Figure 106-3).

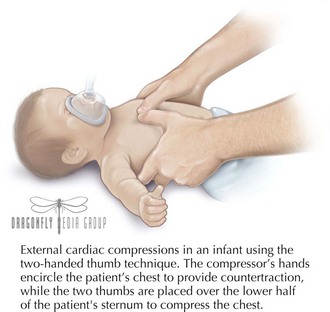

Thirty seconds later, if the heart rate remains less than 60 beats/min with effective positive-pressure ventilation, chest compressions should be initiated with the two-thumb technique. The chest should be compressed to one-third to one-half the anteroposterior diameter of the chest at a ratio of three compressions to one breath given (Figure 106-4). Chest compressions continue until the heart rate rises above 60 beats/min. If, after 30 seconds, the heart rate does not rise, then epinephrine should be administered. Epinephrine can be administered through the endotracheal tube or intravenously (often via the umbilical vein); the intravenous route is preferred because the endotracheal route yields lower serum concentrations. The dose is 0.01 to 0.03 mg/kg of epinephrine diluted to a 1 : 10,000 concentration. Thirty seconds later, the heart rate should be assessed again; if the heart rate remains less then 60 beats/min, epinephrine can be repeated every 3 to 5 minutes until the heart rate increases.

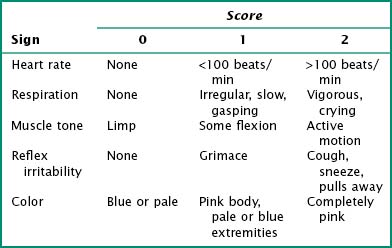

The Apgar scores are also assessed during this time; the infant is given a score at 1 and 5 minutes of life but should continue to be scored every 5 minutes until a score of 7 is achieved (Table 106-2).

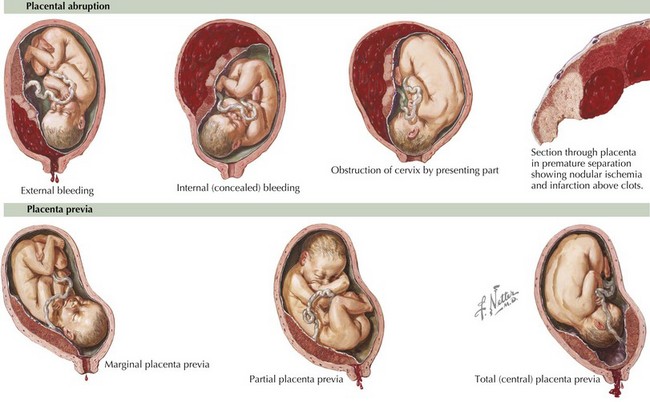

Volume expansion is indicated if the baby still does not respond to resuscitative efforts and appears pale with delayed capillary refill or weak pulses. Hypovolemic shock can result from an acute hemorrhage from a placental abruption or placenta previa or blood loss from the umbilical cord (Figure 106-5). Isotonic, crystalloid solutions, including normal saline and lactated Ringer’s solution, are best for acutely treating hypovolemia. O-negative, Rh-negative packed red blood cells can also be given if there is evidence of fetal anemia or severe fetal blood loss. Volume expansion should be accomplished with small volumes, 10 mL/kg at a time, to decrease the risk of intraventricular hemorrhage.

American Heart Association and American Academy of Pediatrics. 2005 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) of pediatric and neonatal patients: neonatal resuscitation guidelines. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):e1029-e1038.

International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. 2005 International Consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. part 7: neonatal resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2005;67(2-3):293-303.

Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, Aziz K, et al. Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:876-908.

Kattwinkel J, Short J, Boyle D, et al. Textbook of Neonatal Resuscitation, ed 5. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics and American Heart Association; 2006.

Obladen M. History of neonatal resuscitation. part 1: artificial ventilation. Neonatology. 2008;94(3):144-149.

Rajani AK, Chitkara R, Halamek LP. Delivery room management of the newborn. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56(3):515-535.

Stevens TP, Sinkin RA. Surfactant replacement therapy. Chest. 2007;131(5):1577-1582.

Taeusch HW, Ballard R, Gleason C. Avery’s Diseases of the Newborn, ed 8. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. pp 349-363