Neonatal Mucous Membrane Disorders

Lucia Diaz, Adelaide A. Hebert

Introduction

Examination of the mucous membranes is an important, yet often overlooked, part of the neonatal evaluation. This chapter discusses abnormal cutaneous findings of the oral, genital, and ocular systems. Many of these abnormalities provide important clues to the diagnosis of underlying disease and/or developmental syndromes in the newborn infant.1,2

Disorders of the oral mucous membranes

Developmental defects, growths, and hamartomas

See Table 30.1.

TABLE 30.1

Benign papular and nodular lesions of the oral cavity

| Lesion | Morphology | Most common location |

| Bohn’s nodules | Multiple, small cysts | Gingival margin, lateral palate |

| Congenital epulis | Pedunculated, soft nodule from 1 mm to several cm in diameter | Gingival margin |

| Congenital ranula | Translucent, firm papule or nodule | Anterior floor of mouth, lateral to lingual frenulum |

| Epstein’s pearls | Multiple, tiny (< few mm) cysts | Median palatal raphe |

| Eruption cysts | Circumscribed, fluctuant swelling; may have bluish-red to black surface if hemorrhage has occurred | Alveolar ridge of mandible or maxilla |

| Granular cell tumor | Small (<3 cm in diameter), firm, flesh-colored nodule | Tongue |

| Hemangioma | Red to blue, soft to semi-firm nodule | Lip, buccal mucosa, palate |

| Lymphangioma | Translucent papules or nodule | Tongue |

| Neurofibroma | Soft, flesh-colored nodule | Tongue |

| Nevus sebaceus | Verrucous yellow plaques | Lip, gingiva |

| Venous malformation | Bluish, compressible nodule; often intermittently painful | Oropharynx |

| Verrucae | Papillomatous white or pink papules | Lip, tongue, palate |

| White sponge nevus | White plaque with thick, folded surface | Buccal mucosa, tongue |

Bohn’s nodules

Bohn’s nodules are multiple, small cystic structures found along the lingual gum margins and lateral palate (Fig. 30.1). These lesions are commonly found in up to 85% of newborn infants. Bohn’s nodules most likely develop from epithelial remnants of salivary gland tissue or from remnants of the dental lamina. However, some authors refute this idea because mucinous glands are rarely found on the lateral edge of the gingival margins. Bohn’s nodules are felt to be asymptomatic and occur more often in full-term infants than in premature newborns.3–6 Treatment is unnecessary as involution or shedding usually occurs.

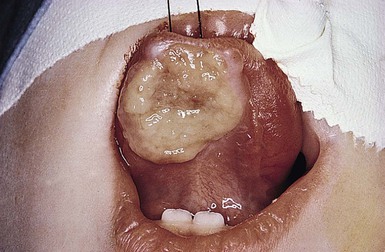

Congenital epulis

A congenital epulis is a rare, benign tumor of the newborn. Clinically, the lesion is a solitary soft nodule, measuring from 1 to several millimeters in diameter, and often pedunculated. The lesion represents a hamartoma of the alveolar ridge.7 The epulis forms over the gingival margin, most frequently along the anterior maxillary ridge or the incisor/canine.8,9 Lesions on the alveolar ridge occur twice as often as on the maxilla.7 Female infants are more often affected, with a female to male ratio of 3 : 2. Fetal ovarian estrogen levels were originally thought to account for this predominance, but this concept has been challenged.10 Currently, there is no known cause of these lesions and no teratogenic or genetic association has been reported.

Histologic examination shows tightly packed granular cells surrounded by a prominent fibrovascular network. The absence of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and neural elements differentiates the epulis from a granular cell myoblastoma.

Lesions may regress spontaneously over time. However, difficulties with feeding and respiration can occur with large or multiple lesions.11 Simple excision is curative; recurrences have not been reported.

Congenital ranula

A congenital ranula is a very rare type of mucocele that results from an obstructed, imperforate, or atretic sublingual or submandibular salivary gland duct. Lesions are found specifically on the anterior floor of the mouth, lateral to the lingual frenulum. The overlying mucosa may be normal in color or have a translucent blue hue. These retention cysts are asymptomatic.

Ranulae may resemble mucous retention cysts, dermoid cysts, or cystic hygromas. Differentiation of a ranula from a mucous retention cyst can be confirmed only by histopathologic examination. Although the mucous retention cyst is a true cyst lined by epithelium, the ranula is a pseudocyst. Ranulae may rupture spontaneously during feeding and sucking; however, lesions that enlarge over time should be treated early with marsupialization with packing. In some cases, failure to operate may lead to sialadenitis. If surgery is warranted, the risk of recurrence postoperatively is minimal.12,13

Epstein’s pearls

Epstein’s pearls are benign cystic lesions that occur along the median palatal raphe, most commonly at the junction of the hard and soft palates (Fig. 30.2). Lesions are multiple and small, ranging in size from less than a millimeter to several millimeters in diameter. The overall appearance is similar to that of Bohn’s nodules, but the location and etiology make this a distinct entity. Epstein’s pearls are common, occurring in 60–85% of newborn infants. Japanese newborns are most commonly affected (up to 92%), followed by Caucasians and African-Americans.4,6,14

Epstein’s pearls are epidermal inclusion cysts formed during the fusion of the soft and hard palates, and contain desquamated keratin within their lumina. They are considered the counterpart of milia, which are commonly seen on the faces of neonates. No therapy is indicated, as most lesions rupture spontaneously within the first few weeks to months of life.3,4,14

Eruption cysts

An eruption cyst (or eruption hematoma) is a circumscribed fluctuant swelling that develops over the site of an erupting tooth (Fig. 30.3). Lesions in the newborn may occur secondary to natal or neonatal teeth, but these cysts are more commonly associated with the eruption of deciduous or permanent teeth. Eruption cysts most commonly develop on the alveolar ridge of the maxilla or mandible. Size varies with the type of tooth overlaid, but most lesions are approximately 0.6 cm in diameter. The surface of the cyst may appear flesh-colored or have a bluish-red to blue-black color if the cyst cavity contains blood. Although removal of the tissue overlying the tooth may aid in its eruption, most eruption cysts resolve spontaneously within several weeks.15

Ectopic thyroid tissue

Ectopic thyroid tissue is defined by the development of thyroid tissue outside the usual pretracheal position (inferior to the thyroid cartilage). This abnormality results from an arrest or irregularity in thyroid descent during embryologic development. Ectopic thyroid tissue, also referred to as a thyroglossal duct cyst, may be classified as lingual, sublingual, pretracheal, or substernal. Lingual is the most common type, representing over 90% of cases. A lingual thyroglossal duct cyst presents as a painless, nodular mass in the cervical midline or at the base of the tongue between the circumvallate papillae and the epiglottis. Lesions may be present at birth or develop in early infancy. However, most become evident during the first or second decades of life, at which time associated symptoms may occur.16–19

Thyroglossal duct cysts are a rare but serious cause of airway obstruction in newborns and infants: mortality rates of up to 43% have been reported. Although usually asymptomatic, lesions may be associated with cough, dysphagia, hemorrhage, or pain. If a cutaneous tract is present, mucous drainage can occur.

Sebaceous hyperplasia of the lip (Fordyce spots or granules)

Fordyce spots are collections of normal sebaceous glands within the oral cavity. Lesions appear as white to yellow macules and papules visible through the transparent oral mucosa. The papules measure 1–3 mm and may be clustered (Fig. 30.4). Plaques form when large numbers of sebaceous glands coalesce. Sebaceous hyperplasia is most commonly seen on the upper lip, but may also be evident on the buccal mucosa, tongue, gingiva, or palate. No treatment is warranted, as these lesions are asymptomatic, resolve spontaneously, and are of no medical consequence.6 Superpulsed CO2 laser has been reported to be safe and effective in a small number of cases.20

Nevus sebaceus

Nevus sebaceus (see Chapter 26) is a common congenital lesion that usually occurs on the scalp and face, but may be seen in continuity with growths in the oral cavity. Cutaneous lesions present as yellow, verrucous plaques (Fig. 30.5) that enlarge with the growth of the child and often become thicker in puberty. Mucosal lesions most often present as linear papillomatous plaques on the gingivae, palate, tongue and buccal mucosa. Intraoral lesions can be associated with dental anomalies and mandibular cysts.21 Extensive and multiple nevus sebaceus may be associated with cerebral, ocular, and skeletal abnormalities as part of sebaceous nevus syndrome.

White sponge nevus (of Cannon)

White sponge nevus is a rare, benign condition inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Typical lesions are asymptomatic white plaques in which the oral mucosa appears thickened and folded, with a spongy texture (Fig. 30.6). The most common location for a white sponge nevus is on the buccal mucosa, often in a bilateral distribution. Extraoral locations, such as labial, nasal, vaginal, esophageal, and anal mucosa, are uncommon, and such lesions usually do not occur in the absence of oral involvement.22 The white sponge nevus is most often present at birth or discovered during early childhood.23

The clinical differential diagnosis of white sponge nevus includes candidiasis, leukoderma, leukoplakia, lichen planus, and local irritation. White sponge nevus is sometimes seen in association with pachyonychia congenita. However, the clinical and histologic findings are usually characteristic enough to differentiate this condition from other white mucosal lesions.24 The histopathology of a white sponge nevus shows epithelial thickening with hyperkeratosis and acanthosis. The suprabasal cells exhibit intracellular edema with pyknotic nuclei and compact aggregates of keratin intermediate filaments within the upper spinous layer.25 White sponge nevus is a benign disorder that does not require treatment.

Granular cell tumor

The granular cell tumor, first described in 1926, was originally thought to arise from skeletal muscle and was hence named a granular cell myoblastoma.26 However, more recent immunohistochemical testing suggests a neural origin.27 Intraoral granular cell tumors most commonly occur on the tongue, but may also affect the lips and gingiva. The lesion is typically a solitary, small (<3 cm), firm, asymptomatic nodule, with a smooth, nonulcerated surface. These lesions may rarely cause obstruction of the oral cavity.28

The differential diagnosis includes other benign neural neoplasms (neuromas, neurofibromas), and vascular tumors (hemangiomas, venous malformations).29–32 Histologically, large, eosinophilic granular cells are arranged in clusters and fascicles. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying epithelium may be present, mimicking squamous cell carcinoma.33

Although the majority of granular cell tumors are entirely benign, these tumors can be locally invasive and metastases have been rarely reported. Surgical excision is recommended and curative. Recurrences are uncommon.34

Neurofibroma

A neurofibroma is a tumor of neural origin, which may occur as an isolated finding or in association with the syndrome of neurofibromatosis. Neurofibromatosis may be difficult to diagnose in the newborn period, when many of the features of the syndrome are not yet evident.

Neurofibromas may be found on the skin or within the oral cavity, although intraoral lesions are exceedingly rare in the newborn. The most common intraoral location is the tongue, though tumors have also been observed over the buccal mucosa and palate. Oral lesions are typically asymptomatic, slow-growing, soft nodules, of the same color as the surrounding mucosa. Neurofibromas range in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters in diameter. Histologically, the tumor is unencapsulated and composed of Schwann cells, perineural cells, and fibroblasts. Neurofibromas are benign and can be electively surgically excised with little risk of recurrence.35,36

Infections

Thrush

The oral mucous membranes are the most frequent site for yeast colonization in infants. Candida albicans causes the white pseudomembranes (thrush) on the palate, gums, gingivae, tongue or buccal mucosa. Removal of the plaques leaves an underlying area of erythema. This is a clinical diagnosis that can be confirmed with KOH or culture. Thrush can be treated with nystatin oral suspension 200 000 units (2 mL) on the tongue four times daily for 7–10 days. Fluconazole may be more effective than oral nystatin and should be considered for treatment failures. Treatment of immunocompromised oropharyngeal candidiasis with systemic azoles can be beneficial.

Black hairy tongue (lingua pilosa nigra)

Black hairy tongue is characterized by accumulation of keratin on the filiform papillae that give the central dorsal tongue a brown-black appearance (Fig. 30.7). This condition is usually seen in adults but has been reported in an infant as young as 2 months of age.37 Although the etiology is unknown, black hairy tongue is attributed to bacterial or yeast infections as well as chronic antibiotic use. Treatment involves improving oral hygiene. Brushing of the tongue with toothpaste three times a day often helps this condition.

Herpangina and hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD)

Herpangina and HFMD (see Chapter 13) are common illnesses caused by echoviruses, predominantly coxsackie A16. Herpangina is characterized by fever, sore throat, anorexia, and sometimes abdominal pain. Multiple 1–2 mm vesicles develop on the uvula, tonsils, pharynx, and soft palate. In HFMD, patients have vesicles and erosions on the buccal mucosa in addition to the oral lesions of herpangina. Patients also have oval gray-white vesicles and erythematous papules and macules on the hands, feet and buttocks.

The diagnosis of both diagnoses above is made clinically but can be confirmed with PCR.38 Treatment is supportive and the course lasts less than 1 week.

Herpetic gingivostomatitis

Herpetic oral infections are usually caused by HSV-1 (see Chapter 13). There may be a prodrome of fever, vomiting, and irritability. The infant may also have tender cervical or submental lymphadenopathy. Small vesicles on an erythematous base may develop on the tongue, palate, pharynx, buccal mucosa, lips and floor of the mouth. In contrast to aphthous ulcers, the lesions coalesce into irregular shallow ulcers. Due to the pain, the infant may have difficulty with feeding.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with a Tzanck smear, viral culture, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Treatment includes supportive care and oral acyclovir. The course usually lasts less than 2 weeks.

Human papillomavirus

Oral verrucae or papillomas occur less frequently in children and infants than other forms of HPV infection (see Chapter 13).39 Exophytic, pedunculated or sessile papules with a papillated white or pink surface can present anywhere on the oral mucosa, but are most common on the tongue, palate, and labial mucosa.39 When associated with laryngeal papillomas the infant or child may also have a hoarse voice or respiratory symptoms.40 Vertical transmission of HPV during delivery, or in utero is the most likely, but horizontal transmission by household members and transmission from sexual abuse are also possible.39–41 If necessary, a clinical diagnosis of oral HPV infection can be confirmed by biopsy. HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 are most commonly found in oral papillomas. Treatment should depend on the severity of the presentation and associated symptoms. Treatment options include watchful waiting (as most spontaneously resolve within 1–2 years); destructive modalities such as cryotherapy and laser; and excision by tangential shave.39

Vascular lesions (see Chapters 21 and 22)

Infantile hemangiomas (IH)

IH of the mucosa in newborns most commonly develop within the first few days to weeks of life. Most often IH involve the oral mucosa (lips, buccal mucosa, or palate), but can also involve the nasal and ocular mucosa (Fig. 30.8). Superficial lesions consist of bright red papules, nodules or plaques, whereas deeper lesions are generally flesh colored, and may have a bluish hue or overlying telangiectasias. Lesions with a combination of both superficial and deep features are also common.

Hemangiomas of the oral cavity are prone to trauma, which can lead to ulceration and/or bleeding, particularly during the newborn period. The lip can also be a high-risk location for deformity and scarring, particularly when lesions ulcerate or are superficial and cross the vermillion border. There is also a known association between hemangiomas in a cervicofacial, or ‘beard’ distribution (preauricular skin, chin, anterior neck, or lower lip) and airway hemangioma. At-risk infants should be followed closely during the newborn period for the development of stridor or other signs of airway compromise, in which case direct visualization of the airway can provide a definitive diagnosis.42,43 Treatment indications and options for hemangioma treatment are discussed in Chapter 21. Ulceration of a lip hemangioma can be particularly difficult to manage owing to the challenges of wound care in this location, and because associated pain can interfere with feeding. Such cases may require additional management with beta blockers, corticosteroids, laser, or excisional surgery.44,45

Lymphatic malformations

Lymphatic malformations (LM) are benign, structural malformations of lymphatic vessels, and are much less common than hemangiomas. They are congenital, but sometimes do not manifest until later in childhood. No known sexual predilection or hereditary predisposition exists. Unlike hemangiomas, LM remain static or undergo slow expansion over time, and rarely undergo any significant degree of involution.46–48

The cervicofacial region is a common site for LM. Lesions may be localized, diffuse or multiple in distribution, and may be microcystic (‘lymphangioma’), macrocystic (‘cystic hygroma’) or combined. Microcystic lesions of the skin present as translucent papules or nodules, which often turn red or purpuric due to intralesional bleeding (Fig. 30.9). The most common location for intraoral LM is the tongue, although the lips, buccal mucosa, palate, or alveolar ridges may also be affected. LM of the tongue most commonly affects the dorsal anterior two-thirds and may result in macroglossia and difficulties with feeding and speech.47–49 Large macrocystic (Fig. 30.10) or combined LM of the posterior triangle of the neck, which often present as fluctuant, flesh-colored tumors, may also involve the floor or the mouth and submandibular space. Bacterial cellulitis occurring within cervicofacial LM is potentially dangerous because of the risks of airway compromise. In such instances, systemic antibiotics should be administered at the first sign of swelling, pain, redness, or systemic toxicity.

Histologically, LM consist of multiple lymphatic channels lined by single or multiple layers of endothelial cells. Treatment is rarely necessary in the first year of life, and is generally reserved for lesions causing functional compromise or cosmetic deformity. MRI is the best means of determining lesion extent and microcystic or macrocystic morphology, which is generally necessary before decisions regarding treatment can be made.

The mainstay of therapy for LM includes surgery and/or sclerotherapy, though cure is rarely achieved except for the smallest, most well-localized lesion. Attempts at surgical resection are often accompanied by a variety of intraoperative and postoperative complications, including recurrence. Sclerotherapy with agents such as absolute ethanol, sodium tetradecyl sulfate, or doxycycline, can be used for treatment of macrocystic LM, alone or in conjunction with surgical techniques.50,51 Microcystic LM of the tongue can also be treated with laser photocoagulation, though this is also a temporary measure.52,53

Venous malformations

Venous malformations (VM) are slow-flow structural anomalies of the venous vasculature, which are generally present at birth but may not manifest until later in childhood. Lesions most commonly involve the face and oropharynx, but may occur in any anatomic location. Though usually solitary, lesions may be multiple, especially when associated with the autosomal dominant, familial cutaneous–mucosal VM syndrome, or blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, both characterized by small dome-shaped lesions. VMs are bluish, compressible nodules, which slowly refill upon release and are often intermittently painful. Lesions may result in skeletal alterations, such as facial asymmetry, dental malalignment, open mouth deformity, and bony hypertrophy.

MRI with or without venography or Doppler ultrasound is the best way to confirm the diagnosis of a venous malformation and determine the extent of tissue involvement. In addition, the presence of phleboliths is highly characteristic of the diagnosis. Extensive lesions may be complicated by a localized, intravascular coagulopathy, characterized by a normal or moderately low platelet count and fibrinogen, increased d-dimers, and normal prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times.

VMs characteristically undergo slow expansion over time. Treatment is rarely necessary in the first years of life, and is generally reserved for lesions leading to functional compromise, bleeding, coagulopathy, or cosmetic disfigurement. Depending on the location and size of the lesion, surgical excision and/or sclerotherapy can be considered.54

Port-wine stain

A port-wine stain (PWS) is a common capillary malformation in newborns. Histopathology shows a normal number of dilated capillaries in the superficial dermis. The well-demarcated vascular stains grow in proportion to the growth of the child.

An orodental PWS may lead to hyperplasia of the gingivae, oral bleeding, overgrowth of bony structures, and possible interruption in dental eruption. This is thought to be from increased blood flow to the areas.55

Pyogenic granuloma

Pyogenic granuloma is an acquired vascular lesion that most commonly presents on the skin, but is not uncommonly seen on the mucous membranes. The typical clinical presentation is a solitary red papule with a collarette of scale at the base that occurs in areas prone to trauma and may bleed. Treatment includes shave excision with electrodesiccation of the base, which helps prevent recurrence. Pulsed-dye laser has been used in smaller lesions.56

Signs of extracutaneous disease

Macroglossia

Macroglossia is defined as a resting tongue that protrudes beyond the teeth or gum line (Figs 30.11, 30.12). When this is present in a newborn, a thorough evaluation should be performed to rule out genetic, metabolic, or other possibly contributing factors. True macroglossia may be ‘primary,’ whereby the tongue is enlarged due to hyperplasia or hypertrophy of normal lingual structures, or, more commonly, ‘secondary’ to an underlying process, as with a lymphangioma or in amyloidosis (Box 30.1).

True macroglossia must be distinguished from pseudomacroglossia. In pseudomacroglossia, the tongue is normal size but functionally enlarged as a result of a small or inferiorly displaced mandible. This situation occurs in the Pierre–Robin syndrome, and is also seen in some newborns ultimately diagnosed with cerebral palsy. An enlarged tongue may affect feeding, speech, and respiration. In later infancy, macroglossia may also cause malocclusion as a result of increased pressure on the teeth.

Surgical trimming or reduction of the tongue is often effective in reducing tissue bulk. Between 4 and 7 years of age is the optimal time for surgical correction if immediate intervention is not mandated by airway obstruction.57 However, therapeutic intervention, when feasible, should be aimed at treating any underlying cause.6

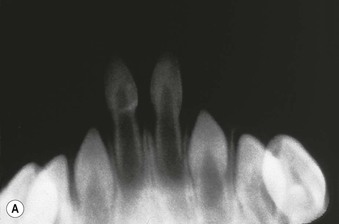

Natal teeth

Natal teeth are defined as teeth present at birth and must be differentiated from neonatal teeth, which erupt during the first month of life. The reported incidence of both natal and neonatal teeth varies widely, but is decidedly rare. Both may occur in either premature or term infants. However, natal teeth occur three times more often than neonatal teeth and are twice as common in females. Two-thirds of natal teeth occur in pairs. The most common location for natal teeth is at the sites of the central mandibular incisors (85%), followed by the maxillary incisors (11%) (Fig. 30.13).58–60 Estimates suggest that only 1–10% of natal teeth are supernumerary.61

Although the exact etiology for natal teeth remains unknown, it appears that the primary tooth bud develops in a more superficial location than normal, and therefore erupts prematurely.62

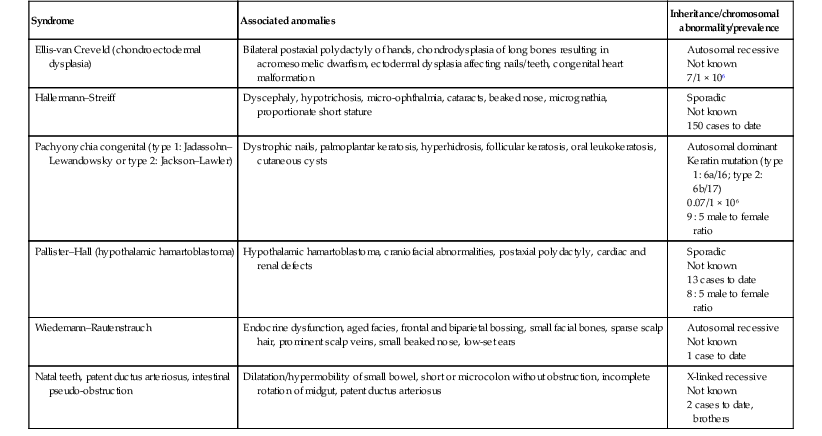

Many syndromes have been associated with natal teeth (Table 30.2), and newborns with this finding should be examined carefully. Reported associations include congenital syphilis, endocrine disturbances, febrile systemic illness, hypovitaminosis, and pyelitis during pregnancy.8

TABLE 30.2

Syndromes associated with natal teeth

| Syndrome | Associated anomalies | Inheritance/chromosomal abnormality/prevalence |

| Ellis-van Creveld (chondroectodermal dysplasia) | Bilateral postaxial polydactyly of hands, chondrodysplasia of long bones resulting in acromesomelic dwarfism, ectodermal dysplasia affecting nails/teeth, congenital heart malformation | |

| Hallermann–Streiff | Dyscephaly, hypotrichosis, micro-ophthalmia, cataracts, beaked nose, micrognathia, proportionate short stature |

(Reproduced with permission from Hebert AA. Mucous membrane disorders. In: Schachner LA, Hansen RC, eds. Pediatric dermatology, Volume 1, 4th edition. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2011.)

Natal teeth usually represent deciduous rather than supernumerary teeth, which can be distinguished by radiography. Supernumerary teeth are extraneous teeth, which should be extracted as they may interfere with normal tooth eruption. The lower central incisors are normally the first teeth in the oral cavity to erupt. The condition of Riga–Fede describes a traumatic ulcerative lesion of the tongue or frenulum, produced when an infant rakes the tongue over the primary lower incisors, which may be mobile and/or have poorly formed crowns (Fig. 30.14). This condition may be related to pain insensitivity, and has been associated with familial dysautonomia,8,63 although Riga–Fede can be seen in normal newborns. This oral ulcerative condition has also been associated with congenital autonomic dysfunction, microcephaly, Lesch–Nyhan syndrome and Tourette syndrome.64

Treatment of natal teeth is dependent on morphology, the amount of root development, and mobility. A pediatric dentist should be involved in the care plan. Two cases were managed by covering the incisal margin with photopolymerizable resin which facilitated the healing of the ulcerations.59 If the tooth is only minimally loose, it will tend to stabilize over time and can be left in place. Problematic teeth should be extracted to prevent trauma or aspiration.65,66 In the setting of a tongue ulceration of Riga–Fede disease, prompt diagnosis and management is essential to avoid deformity or mutilation of the tongue, dehydration and poor growth.67 In all newborns, the administration of prophylactic vitamin K (0.5–1.0 mg IM) is recommended before tooth extraction due to the potential risk of hemorrhage.68

Congenital fistulae of the lower lip

Congenital fistulae of the lower lip (or lip pits) are rare developmental anomalies. The estimated frequency of lower lip pits in Caucasians is uncommon, with approximately 1 in 100 000 persons affected; the frequency in the black population is rare. Clinically, bilateral indentations are seen on the vermillion portion of the lower lip. The pits are usually 1 cm apart and equidistant from the midline. The defect results from incomplete closure of the furrows on the fetal mandibular process. The pits range in depth from a few millimeters to 25 mm; longer fistulae can traverse the orbicularis oris muscle. The proximal opening of the fistula at the lip may extrude saliva, either spontaneously or during mastication. Histologically, the fistula lumen is lined by stratified squamous epithelium, similar to lip mucosa. At the distal end of the fistula, scattered acini of mucinous glands with tubular ducts are present. True salivary glands are not seen.6,69

Congenital fistulae are inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with an estimated penetrance of 80–100%. The presence of a single fistula is considered an incomplete expression of the trait and not a separate entity. Less severe forms may occur and present as simple elevations of a portion of the vermillion border or as an isolated ptosis of the lower lip.70 The evaluation of a patient with lower lip pits should include a search for other possible anomalies. Lip pits are strongly associated with the formation of cleft lip and/or palate. This association approaches 80% and is now referred to as the Van de Woude syndrome. Nearly all cases of Van de Woude syndrome have shown linkage to a region at chromosome 1q32–p41 or 1p34. This autosomal dominantly inherited clefting syndrome shows high penetrance but variable expressivity.71 Newborn infants with single lip pits are at equal risk with those having double pits for associated clefting. Congenital fistulae of the lip are only treated to correct visible deformity or to eradicate significant aberrant salivation.6,69,70,72–74

The best time for surgical repair of the lower lip may be between 10 and 12 months of age. Surgical intervention at this time also helps with parental concerns to normalize the appearance of their child.74

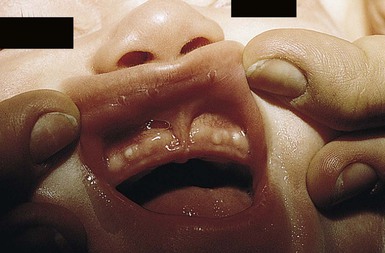

Orofacial–digital syndrome, type I

Orofacial–digital (OFD) syndrome is a rare and complex condition. Nine types are currently recognized.75 Oral abnormalities are the most consistent and characteristic findings of type I OFD (also known as Papillon–Léage–Psaume syndrome). Features may include multiple hyperplastic frenula between the buccal mucosa and alveolar ridge, cleft lip (45%) or palate (80%), a lobated or bifid tongue (30–40%) with small hamartomas (70%) (Fig. 30.15), dental caries, and/or anomalous anterior teeth. Distinguishing facial features are frontal bossing, hypoplasia of the malar bones and alar cartilages, a broad nasal root, and milia of the ears. Skeletal findings include asymmetric shortening of digits, clinodactyly and brachydactyly of the hands (45%), and unilateral polydactyly (25%) of the feet. Infants may also have a dry, rough scalp with significant alopecia.

This form of OFD is part of a heterogeneous group of PFD syndromes.76 The OFDI gene is named Cxof5 (Xp22.2–22.3). The condition is seen in one in 50 000 live births.

Newborns with OFD type I may also have internal manifestations, the most common of which are multiple renal, hepatic, or pancreatic cysts. OFD I is considered a distinct subset of this syndrome because of the X-linked dominant inheritance pattern and this association with polycystic kidney disease.76

Significant CNS abnormalities, especially agenesis or absence of the corpus callosum, also occur. The overall prognosis is poor: one-third of affected patients die within the first year of life. Therapy must be individualized based on the presence of visceral anomalies. Surgical intervention may be necessary to ensure proper feeding and oral communication.6,77,78

Oral and genital ulcerations with immunodeficiency

The presentation of oral and genital ulcers in a newborn may be a sign of underlying congenital immunodeficiency. In particular, ulcers in these locations appear to be a distinctive marker and are often the presenting feature of severe combined immunodeficiency disease with T- and B-cell lymphopenia (T−B−SCID) in Athabascan-speaking Native American infants.79 In this population, ulcers are typically punched-out and deep, albeit without invasion to underlying structures, and do not result in functional sequelae or significant scarring. This is to be distinguished from the condition noma neonatorum, which is a rare condition of preterm infants in developing countries. Noma neonatorum causes aggressive orofacial tissue gangrene, accompanied by a high mortality rate, and is most commonly associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis.80,81 In contrast, the ulcers found in Native American children with T−B−SCID are most likely a result of T-cell immunodeficiency combined with a genetic predisposition. In such children, treatment of the underlying condition with bone marrow transplantation results in resolution of the ulcers. Early recognition and diagnosis can lead to prompt intervention and prevention of complications.79

Behçet disease

Behçet disease is a complex, multisystem disease characterized clinically by the presence of oral aphthae and at least two of the following: genital aphthae, synovitis, cutaneous pustular vasculitis, posterior uveitis, or meningoencephalitis. The most common features of neonatal Behçet disease are oral ulcerations, skin lesions, fever and leukocytosis but only half of the patients described would fulfill the classic diagnostic criteria (based on an adult patient series). In addition, a treatment consensus for neonatal Behçet disease has yet to be published.82 Neonatal cases have been described in which affected mothers had oral and genital ulcerations during pregnancy.83,84 A case of transient neonatal Behçet disease with life-threatening complications has been reported.85

Although uncommon, pediatric Behçet disease does occur. In comparison with adults, oral and genital ulcers are less common in children with Behçet disease. Uveitis, however, is more common. As in adults, ocular lesions in children pose a serious threat because they may lead to blindness.86

Acatalasemia

Acatalasemia is a genetically heterogeneous disease characterized by an inherited absence of the enzyme catalase. Affected infants are unable to degrade endogenous or exogenous hydrogen peroxide, which accumulates, resulting in oxidation deprivation. The soft tissues of the mouth and nasal mucosa are preferentially affected, leading to ulceration, necrosis, and in severe cases gangrene. The physical examination is otherwise normal. The diagnosis is confirmed by the absence of blood catalase. Therapy consists of meticulous oral hygiene, early removal of diseased teeth and tonsils, and the administration of systemic antibiotics as necessary to control bacterial proliferation.6,87

Pigmentary disorders

Lingual melanotic macule

Congenital lingual melanotic macules have been observed as solitary or multiple, well-circumscribed, brown lesions on the dorsal surface of the tongue at birth that grow proportionately to the tongue (Fig. 30.16). Histological features are those of increased basal pigmentation with minimal melanocytic hyperplasia and mild pigment incontinence. It is distinct from macular pigmentation, and appears to be a benign process. The diagnosis of congenital lingual melanotic macule should be considered if the pigmented macules are present at birth and grow proportionately with the child.88

Macular pigmentation

Macular pigmentation of the oral mucosa is a normal variant found in darker-skinned persons. Several patterns of pigmentation may occur. Most commonly, a pigmented band is present at the junction of the free and attached alveolar mucosa. Patchy pigmentation may also be evident over the buccal mucosa, on the lips, and on the floor of the mouth (Fig. 30.17). When the tongue is involved, which is rare, the pigment is localized to the filiform papillae. The increased pigmentation occurs as a result of an increase in melanocytic activity rather than an increase in the number of melanocytes. No therapy is necessary.89

Miscellaneous lesions

Annulus migrans (geographic tongue)

Annulus migrans is a common condition that may present as early as 2 weeks of life. Another name for this condition is benign migratory glossitis. Characteristically, erythematous patches are due to depapillation. The lesions are often migratory and transient in nature. The etiology of annulus migrans is most likely reactive in nature; reported associated disorders have included psoriasis (especially pustular), Reiter syndrome, atopic and seborrheic dermatitis, and spasmodic bronchitis of childhood. Histologically, geographic tongue is indistinguishable from pustular psoriasis or Reiter syndrome. Therapy of this benign condition is generally unsuccessful and unwarranted.6,90

Sucking calluses

Sucking calluses (or sucking pads) develop on the lips or buccal mucosa as solitary, oval thickenings (Fig. 30.18). When these lesions are congenital, they are indicative of vigorous sucking in utero. Presentation after birth is more common in breastfed black infants.91 Histology reveals a thickened epidermis secondary to intracellular edema and hyperkeratosis. Sucking calluses involute spontaneously within a few days or weeks after birth, or on cessation of breastfeeding.6,14

Bednar’s aphthae

Bednar’s aphthae are ulcers located on the posterior palate that are thought to be from trauma. They are large and tend to coalesce. Pacifiers and vigorous sucking may be responsible. The differential diagnosis includes herpangina and herpetic stomatitis. Treatment of the lesions includes minimizing trauma.

Disorders of the genital mucous membranes

Labial adhesions

Labial adhesions92 are exceedingly rare during the newborn period. The rarity of this finding has been attributed to the presence of maternal estrogens at birth. Infants between the ages of 13 and 23 months are most commonly affected, with an incidence of 3.3%. Clinically, a thin membrane extends between the labia, which may partially or completely conceal the vaginal opening. Recommended treatments include A+D Ointment® for asymptomatic cases, and topical estrogen cream or ointment if urinary or vaginal drainage is impaired.93,94 Use of potent topical steroids have been reported in prepubertal patients but few references to the neonatal period are available.92

Perianal pyramidal protrusion

Perianal pyramidal protrusion (see Chapter 17) is an increasingly recognized entity characteristically located on the perineal median raphe, anterior to the anus. Clinically the lesion is pyramidal in shape, with a smooth, red, or rose-colored surface (Fig. 30.19). The average age at presentation is 14.1 months, and 94% occur in females. Histologic examination shows epidermal acanthosis, marked edema in the upper dermis, and a mild dermal inflammatory infiltrate.95 The pathogenesis is unknown, but some cases have been related to constipation and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus.96,97 This condition is not associated with child abuse. Differential diagnosis includes genital warts, granulomatous lesions of inflammatory bowel disease, rectal prolapse, hemorrhoids, acrochordons, and perineal midline malformation. Although most lesions show spontaneous reduction without any specific treatment, treating associated constipation may hasten resolution.95,98,99

Perineal groove

A moist sulcus extending from the posterior fourchette to the anterior edge of the anus is called a perineal groove (Fig. 30.20). Theories as to why this rare congenital malformation occurs include distorted fusion of the medial genital folds in the central area between the perineal raphe and the vestibule or as a function of an open cloacal duct.100–103 In those young girls with the perineal groove who tend to develop recurrent infections, treatment with surgical excision of the groove is recommended.102

Hymenal tag

Hymenal tags are fleshy protrusions that extend from the hymen. These have been defined as a ‘flap’ or ‘appendage’ extending ≥1 mm from the hymenal rim.104 Tags develop more often superiorly and inferiorly on the hymen (rather than on the lateral portion) due to their origin from the septa.105 Hymenal tissue may be observed to be redundant in neonates and a portion of the hymen may appear translucent.106 Tags may be present and noted at the time of birth or may develop during early childhood. No therapy is warranted.

Urethral retention cyst

The urethral retention cyst is an inclusion cyst that forms at the urethral opening in newborn boys. This lesion is simply a milium, which develops either as a result of friction or from remnants of epithelial tissue trapped along a line of skin fusion. No therapy is necessary, as the white, firm, smooth-surfaced papule will rupture spontaneously and be shed during the first weeks of life. These cysts are not likely to cause urinary retention or symptoms.107

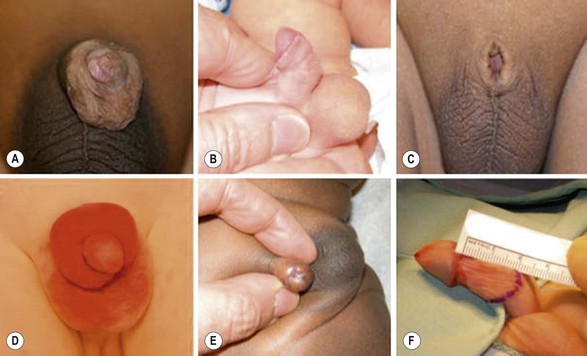

Adhesions after circumcision

The estimated rate of newborn circumcision in the USA is approximately 65% of all male offspring. While the vast majority of circumcisions are without postoperative complications, re-evaluations of the surgical site represented 7.4% of pediatric urology visits in one outpatient clinic.108 The most common finding that resulted in revision circumcision was the presence of excess foreskin resulting in an uncircumcised appearance and a poor cosmetic outcome. Other complications can include: preputial adhesions, meatal stenosis skin bridges, aborted circumcisions due to hypospadias, recurrent phimosis, paraphimosis, iatrogenic buried penis, penile rotation, and wound dehiscence. Examples of late complications are seen in Figure 30.21![]() . The majority of such surgical complications are said to be avoidable by the use of meticulous circumcision technique and careful postoperative wound care.108

. The majority of such surgical complications are said to be avoidable by the use of meticulous circumcision technique and careful postoperative wound care.108

The etiology of penile adhesions after circumcision is unknown but these may result from incomplete lysis of the physiological adhesions at circumcision.109 Following circumcision, two moist surfaces touch each other and that phenomenon may lead to the formation of adhesions that are circumferential or single synechial bands. The majority of these bands with resolve without intervention over time. The longer the time period between the circumcision, the less likely it is that adhesions will form.109

Lichen sclerosis

Lichen sclerosis (see Chapter 17) is rare in the neonate but may develop in infancy and most often affects females. The classic morphology in females is white, glistening atrophic plaques on the vulvar and perineal skin with occasional telangiectasias and fine wrinkling of the skin. Pruritus, constipation, dysuria and pain are common associated symptoms. Progressive anatomic distortion may occur if lichen sclerosis is left untreated. High potency topical steroids are the treatment of choice, but the disease may recur after treatment is stopped.

The characteristic findings in males are sclerotic white porcelain-like alterations at the distal portion of the prepuce (Fig. 30.22). These changes, which may present as a whitish ring on the distal penis, can cause progressive phimosis. Cicatricial phimosis should prompt an evaluation for lichen sclerosis. The ultimate degree of involvement of the meatus and urethra depends on the disease severity and the duration of the sclerosis before adequate intervention occurs. Lichen sclerosis is seen more often in males with hypospadias. Ultimately 10–40% of all surgically treated phimosis cases are due to lichen sclerosis. In males, the name balanitis xerotica obliterans refers to the prepubertal form of lichen sclerosis.110 Treatment is with topical steroids if the disease is mild, but surgery with total circumcision yields the most definitive clinical cure. The resected foreskin should be examined histologically to confirm the diagnosis.

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is an ulcerative skin disorder most commonly seen on the lower legs of adults. In adults, it is often associated with an underlying systemic disease, especially ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, or leukemia. The condition is rare in children (4% of cases), and rarer still in infants less than 2 years of age. Diagnosis in infancy is challenging because of the atypical location of lesions (perianal or genital) and the lack of associated systemic illness. Differential diagnosis in infancy includes ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Pseudomonas infection, herpes simplex infection, and severe diaper dermatitis. Successful treatment has been reported with systemic, topical, and intralesional corticosteroids.111

Disorders of the ocular mucous membranes

Congenital obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct

Congenital obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct is the most common abnormality of the lacrimal system in children. Up to 6% of newborn infants are affected. Symptoms typically begin shortly after birth and are variable. Many infants will have only a wet-looking eye or overflow tearing, but most will have recurrent infections manifested by reflux or mucopurulent material from the lacrimal sac. The majority of nasolacrimal duct obstructions clear spontaneously. Simple medical management with antibiotics and massage may hasten resolution. When spontaneous resolution does not occur, ophthalmologic probing and/or irrigation may be required.112,113

Mucocele of the lacrimal sac

The mucocele of the lacrimal sac is a rare anomaly. It presents at birth or shortly thereafter as a bluish, cystic swelling located just below the medial canthus. The lesion is typically about 1 cm in diameter and may be confused with a hemangioma because of its color. Blockage of both the proximal and distal ends of the lacrimal drainage system leads to the accumulation of mucus within the lacrimal sac. The natural course is variable. In some cases the blockage may open spontaneously, but many lesions become infected and/or inflamed with erythema, edema, and surrounding cellulitis. Treatment includes gentle application of warm compresses and systemic antibiotics if infection is suspected. Mucoceles unresponsive to conservative treatment may require ophthalmologic probing.112

Blepharitis and chalazion

Seborrheic blepharitis is an inflammatory condition of the eyelid margin. In infants, seborrheic blepharitis usually occurs in association with dermatitis of the scalp (termed cradle cap) or diaper area, and is most commonly seen between the second and 10th weeks of life. The lid margins are typically erythematous and scaly, with accumulation of debris at the base of the lashes. The severity of the blepharitis usually correlates with degree of dermatitis and rarely may cause a superficial, marginal keratitis.

Treatment of seborrheic blepharitis consists of warm water compresses and gentle cleansing using a dilute amount of an isotonic (baby) shampoo. If necessary, a soft-bristled toothbrush can be used to mechanically remove the scale. A low-potency, non-fluorinated corticosteroid (hydrocortisone) or sulfacetamide ointment may then be gently massaged into the lid margin. These procedures should be repeated daily until the blepharitis has subsided.114

A chalazion is caused by inflammation of a meibomian gland of the upper or lower eyelid. It presents with an erythematous, tender nodule on the lid margin. Most chalazia resolve without treatment, but patients may benefit from warm compresses, and lid hygiene (as described above). Oral azithromycin or erythromycin should be considered if there are corneal changes. If severe and persistent, patients should be referred for excision.

Blepharitis, conjunctivitis, or a chalazion may also be seen in association with periorificial dermatitis, a form of acne rosacea. Patients develop erythematous papules or pustules in the perioral, nasolabial, and periocular locations. Additional ocular findings include hyperemia, photophobia, episcleritis, keratoconjunctivitis and rarely corneal ulcers.115 The etiology of periorificial dermatis is unknown but may be precipitated or prolonged by the use of topical or inhaled steroids.116 Periorificial dermatitis is self-limited but may take months to resolve. Patients should be screened for ocular symptoms and referred for ophthalmologic evaluation if ocular symptoms are severe. Treatment includes topical or oral antibiotics such as erythromycin, azithromycin, or metronidazole (see Chapter 25).

Molluscum conjunctivitis

Molluscum contagiosum can present on the lid or lid margin in infants and young children. In most cases the lesions are small and umbilicated, but lesions can occasionally be multiple and >1 cm. Keratoconjunctivitis may be present and may lead to corneal complications.117 If asymptomatic, no treatment is necessary. However, if ocular symptoms are present, patients should be referred to ophthalmology.

Colobomata

The term coloboma describes a defect such as a notch, gap, fissure, or hole caused by the loss of ocular tissue or an ocular structure (Fig. 30.23). Colobomata may occur as an isolated anomaly, but are most frequently associated with chromosomal defects, especially trisomies 13 and 18, often in association with significant central nervous system abnormalities.118 Infants with the CHARGE syndrome (congenital heart disease, choanal atresia, growth and/or mental retardation, genital hypoplasia, ear anomalies and/or deafness) have a 79% incidence of colobomata.119,120 Colobomata may occasionally be associated with an impaired vision. Retinal colobomas are also a regular feature of the CHIME syndrome (see Chapter 19).

Glaucoma

In infants, the principal signs of glaucoma are tearing, conjunctival hyperemia, photophobia, blepharospasm, corneal clouding, and an enlargement of the cornea and globe, referred to as buphthalmos (Fig. 30.24). Glaucoma in infants is usually due to a developmental disorder in which residual mesodermal tissue impedes the drainage of aqueous humor from the anterior chamber. This primary or simple congenital glaucoma is probably a multifactorial, recessively inherited condition. Other major causes of glaucoma in children are trauma, intraocular hemorrhage, ocular inflammatory disease, and intraocular tumors. Infantile glaucoma has been associated with a variety of other ocular conditions as well as a number of systemic disorders. Those systemic disorders relevant to the dermatologist include Sturge–Weber syndrome, neurofibromatosis, the congenital infection (TORCH) syndromes, and juvenile xanthogranulomas.

Access the full reference list at ExpertConsult.com ![]()

Figure 21 is available online at ExpertConsult.com ![]()