Chapter 184 Neisseria meningitidis (Meningococcus)

Clinical Manifestations

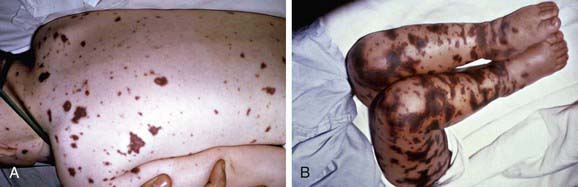

Acute meningococcemia may initially mimic illnesses caused by viruses or other bacteria, causing pharyngitis, fever, myalgias, weakness, vomiting, diarrhea, and/or headache. A fine maculopapular rash is evident in about 7% of cases, with onset typically early in the course of infection. Limb pain, myalgias, or refusal to walk occurs often and is the primary complaint in 7% of otherwise clinically unsuspected cases. Cold hands or feet and abnormal skin color are also early signs. In fulminant meningococcemia, the disease progresses rapidly over several hours from fever without other signs to septic shock characterized by prominent petechiae and purpura (purpura fulminans), hypotension, DIC, acidosis, adrenal hemorrhage, renal failure, myocardial failure, and coma (Fig. 184-1). Meningitis may or may not be present.

Figure 184-1 A, Purpuric rash in a 3 yr old with meningococcemia. B, Purpura fulminans in an 11 mo old with meningococcemia.

(From Thompson ED, Herzog KD: Fever and rash. In Zaoutis L, Chiang V, editors: Comprehensive pediatric hospital medicine, Philadelphia, 2007, Mosby, p 332, Figs. 62-6 and 62-7.)

Treatment

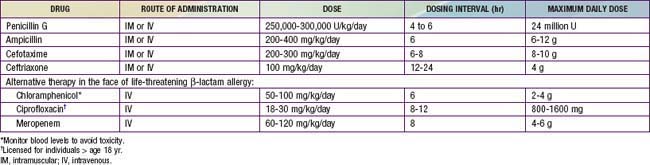

Empirical therapy should be initiated immediately for possible invasive meningococcal infections. β-Lactam antibiotics are the drugs of choice. Because of concerns about penicillin- or cephalosporin-resistant S. pneumoniae, intravenous (IV) vancomycin (60 mg/kg/day, divided in four doses, each dose given every 6 hr) should be added empirically as a second drug as part of initial empiric regimens for bacterial meningitis of unknown cause (Chapter 595.1). More specific therapy for meningococcal disease may be initiated when culture and antibiotic susceptibility results become available (Table 184-1). Although ciprofloxacin may be an alternative to cephalosporins for treatment of meningococcal infection, ciprofloxacin-resistant meningococci have been identified. Therapy in children is generally continued for 5-7 days.

Prevention

Close contacts of patients with meningococcal disease are at increased risk for infection. Antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated for household, daycare, and nursery school contacts and for anyone who has had contact with the patient’s oral secretions during the 7 days before onset of illness. Prophylaxis of contacts should be offered as soon as possible (Table 184-2), ideally within 24 hr of diagnosis of the patient. Because prophylaxis is not 100% effective, close contacts should be carefully monitored and brought to medical attention if they experience fever. Prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for medical personnel except those with intimate exposure, such as through mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, intubation, or suctioning before antibiotic therapy was begun.

Table 184-2 ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS TO PREVENT NEISSERIA MENINGITIDIS INFECTION

| DRUG | DOSE | DURATION |

|---|---|---|

| Rifampin: | 2 days (4 doses) | |

| Infants <1 mo | 5 mg/kg PO every 12 hr | |

| Children >1 mo | 10mg/kg PO every 12hr | |

| Adults | 600 mg PO every 12 hr | |

| Ceftriaxone: | ||

| Children <15 yr | 125 mg IM | 1 dose |

| Children >15 yr | 250 mg IM | 1 dose |

| Ciprofloxacin, persons >18 yr | 500 mg PO | 1 dose |

IM, intramuscular; PO, by mouth.

Vaccination

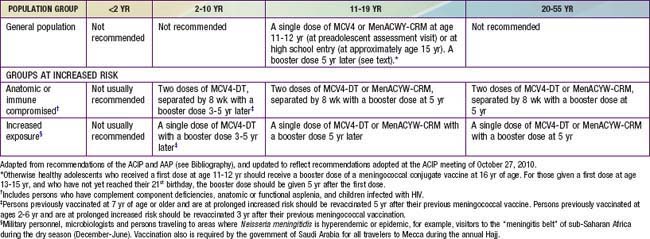

In the USA, routine meningococcal vaccination is recommended for all children beginning at age 11 yr. In this age group, about 75% of meningococcal disease is caused by strains with capsular groups C, Y, or W-135 and therefore is potentially vaccine preventable. On the basis of reviews of age-related immunogenicity, disease burden, and cost effectiveness, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) do not recommend routine meningococcal vaccination for children < 11 yr. Beginning at age 2 yr, vaccination should be given to children with underlying conditions associated with increased risk of meningococcal disease (Table 184-3). As of October 2010, MPSV4 and MCV4-DT are the only vaccines approved by the FDA for use in this age group. MenACWY-CRM, however, is reported to be safe and immunogenic in children 2-10 yr, and regulatory approval by the FDA for this age group is under consideration.

Recommendations for meningococcal vaccination can be found in Table 184-3. MCV4-DT or MenACWY-CRM as a single dose is routinely recommended for all adolescents at 11-12 yr at the preadolescent visit, and adolescents at age 15 yr or high school entry if not previously vaccinated. MPSV4 remains an acceptable alternative for this age group when conjugate vaccines are unavailable. MCV4-DT or MenACWY-CRM and the Tdap (tetanus and diphtheria toxoids and acellular pertussis booster) vaccine should be administered at separate injection sites to adolescents during the same visit if both vaccines are indicated. If this is not feasible, the meningococcal conjugate vaccines and Tdap can be administered in either sequence with a minimum interval of 1 mo between vaccines. MenACWY-CRM also can be administered at separate injection sites with Tdap and HPV vaccines. Either conjugate vaccine is also recommended for all incoming college freshmen living in dormitories who have not been previously immunized with a meningococcal vaccine. Many colleges and universities, and some states, have mandated meningococcal immunization of all matriculating freshmen. Because of waning immunity, otherwise healthy adolescents who received a first dose at age 11-12 yr should receive a booster dose of a meningococcal conjugate vaccine at 16 yr of age. For those given a first dose at age 13-15 yr, and who have not yet reached their 21st birthday, the booster dose should be given 5 yr after the first dose.

Allport T, Read L, Nadel S, et al. Critical illness and amputation in meningococcal septicemia: is life worth saving? Pediatrics. 2008;122:629-632.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Licensure of a meningococcal conjugate vaccine (Menveo) and guidance for use—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:273.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendation from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for revaccination of persons at prolonged increased risk for meningococcal disease. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1042-1043.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP): decision not to recommend routine vaccination of all children aged 2–10 years with quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV4). MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:462-465.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices to vaccinate all persons aged 11–18 years with meningococcal conjugate vaccine. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:794-795.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendation from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for revaccination of persons at prolonged increased risk for meningococcal disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1042-1043.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Licensure of a meningococcal conjugate vaccine (Menveo) and guidance for use—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;59:273.

Cohn AC, MacNeil JR, Harrison LH, et al. Changes in Neisseria meningitidis disease epidemiology in the United States, 1998–2007: implications for prevention of meningococcal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:184-193.

Davila S, Wright VJ, Chuen Khor C, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the CFH region associated with host susceptibility to meningococcal disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:772-776.

Gardner P. Clinical practice: prevention of meningococcal disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1466-1473.

Granoff DM. Relative importance of complement-mediated serum bactericidal and opsonic activity for protection against meningococcal disease. Vaccine. 2009;27(Suppl 2):B117-B125.

Granoff DM, Harrison L, Borrow R. Meningococcal vaccines. In: Plotkin SA, Offit P, Orenstein WA, editors. Vaccines. ed 5. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2008:399-434.

Harrison LH, Kreiner CJ, Shutt KA, et al. Risk factors for meningococcal disease in student in grades 9–12. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:193-199.

Hart CA, Thomson AP. Meningococcal disease and its management in children. BMJ. 2006;333:685-690.

Heckenberg SGB, de Gans J, Brouwer MC, et al. Clinical features, outcome, and meningococcal genotype in 258 adults with meningococcal meningitis. Medicine. 2008;87:185-192.

Maiden MC, Ibarz-Pavon AB, Urwin R, et al. Impact of meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccines on carriage and herd immunity. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:737-743.

Nascimento-Carvalho CM, Moreno-Carvalho OA. Changing the diagnostic framework of meningococcal disease. Lancet. 2006;367:371-372.

Snape MD, Perrett KP, Ford KJ, et al. Immunogenicity of a tetravalent meningococcal glycoconjugate vaccine in infants. JAMA. 2008;299:173-184.

Thompson MJ, Ninis N, Perera R, et al. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet. 2006;367:397-403.

Vu DM, Welsch JA, Zuno-Mitchell P, et al. Antibody persistence 3 years after immunization of adolescents with quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:821-828.

Wu HM, Harcourt BH, Hatcher CP, et al. Emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant Neisseria meningitidis in North America. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:886-892.

Wright V, Hibber M, Levin M. Genetic polymorphisms in host response to meningococcal infection: the role of susceptibility and severity genes. Vaccine. 2009;27(Suppl 2):B90-B102.