23.7 Needle thoracostomy

Background

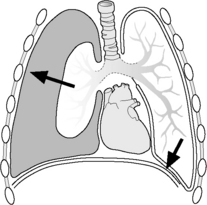

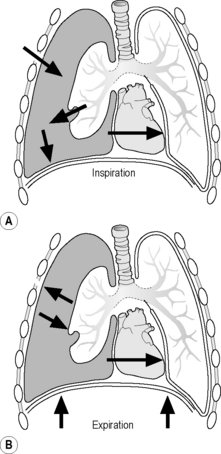

Normally, the visceral and parietal pleura are closely adherent to one another. However, if either surface is violated, air enters into the potential space between visceral and parietal pleura, creating a simple pneumothorax (Fig. 23.7.1). This typically occurs in the setting of blunt or penetrating trauma. Occasionally, spontaneous pneumothorax occurs, as with excessive air trapping in an asthmatic child. If enough air collects, a tension pneumothorax can develop in which pressure in the space shifts the mediastinum, impedes venous return to the heart, and decreases cardiac output (Fig. 23.7.2). Another pathophysiological mechanism for tension pneumothorax occurs when a patient with a simple pneumothorax is intubated – positive pressure ventilation will force air into the pleural space resulting in a tension pneumothorax. Tension pneumothorax can progress to shock and cardiopulmonary arrest.

Needle evacuation of the air between the visceral and parietal pleura and conversion of the tension pneumothorax to an open pneumothorax will re-expand the lung and improve venous return and cardiac output. Needle thoracostomy is a temporising procedure. Immediately after needle thoracostomy, insert a chest tube to provide ongoing drainage in a closed system (Chapter 23.8). The risk of not performing needle thoracostomy in a child spiralling towards death from a tension pneumothorax is far greater than the risk of performing the procedure in a child without a pneumothorax.

Indications

Contraindications

Preparation

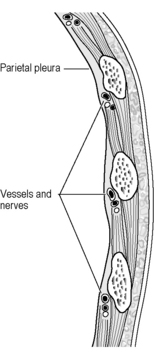

Inspect the anatomy of the ribs and select an entry site above the rib that avoids injuring the intercostal neurovascular bundle (Fig. 23.7.3).

Inspect the anatomy of the ribs and select an entry site above the rib that avoids injuring the intercostal neurovascular bundle (Fig. 23.7.3). Position the child supine with the head of the bed angled up at 30 degrees. Have an assistant gently restrain the conscious child.

Position the child supine with the head of the bed angled up at 30 degrees. Have an assistant gently restrain the conscious child. Identify the 2nd intercostal space (above the 3rd rib) at the midclavicular line. This space is ideal since air in the pleural space rises and typically collects toward the top of the lungs. A lateral approach is an alternative, but may have more complications, including lung penetration and subsequent adhesions.

Identify the 2nd intercostal space (above the 3rd rib) at the midclavicular line. This space is ideal since air in the pleural space rises and typically collects toward the top of the lungs. A lateral approach is an alternative, but may have more complications, including lung penetration and subsequent adhesions.Procedure

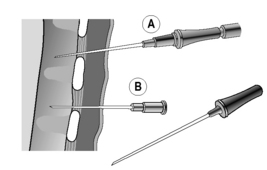

Insert the catheter into the chest wall at a 90 degree angle above the 3rd rib (2nd intercostal space) at the midclavicular line (Fig. 23.7.4A).

Insert the catheter into the chest wall at a 90 degree angle above the 3rd rib (2nd intercostal space) at the midclavicular line (Fig. 23.7.4A). Provide back pressure on the syringe. Once there is a free flow of air in the syringe, continue to pull back on the plunger to evacuate the air.

Provide back pressure on the syringe. Once there is a free flow of air in the syringe, continue to pull back on the plunger to evacuate the air.If there is an open connection between the chest wall and the pleural space from a penetrating injury – an open pneumothorax or sucking chest wound – cover with a petrolatum gauze, extending 6–8 cm from the wound edges on all sides and taped on three sides, to stop further air entry during inspiration (Fig. 23.7.5). Leave one side free to allow for the ongoing egress of air from the pleural space.

Complications

Tips

Barton E.D., Epperson M., Hoyt D.B., Rosen P. Prehospital needle aspiration and tube thoracostomy in trauma victims: A six-year experience with aero medical crews. J Emerg Med. 1995;13(2):155-163.

Bliss D., Silen M. Paediatric thoracic trauma. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(11 Suppl):S409-S415.

Wright S.W. Tube thoracostomy. In Roberts J.R., Hedges J.R., editors: Clinical procedures in emergency medicine, 3rd ed, Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1998.

Zimmerman K.R. Needle thoracostomy. In: Dieckmann R.A., Fiser D.H., Selbst S.M., editors. Paediatric emergency and critical care procedures. St Louis, MO: Mosby, 1997.