12 Neck and cervical spine

The commonest orthopaedic cause of neck disorders is degeneration of a cervical intervertebral disc. This may lead to protrusion of part of the disc contents (prolapsed cervical disc) or, more often, it may give rise to secondary osteoarthritic changes in the intervertebral joints (cervical spondylosis). These conditions together make up a large proportion of the disabilities of the neck encountered in an orthopaedic out-patient department. Another major cause of prolonged pain and stiffness of the neck is the common post-traumatic musculo-ligamentous strain known generally as whiplash injury.

SPECIAL POINTS IN THE INVESTIGATION OF NECK COMPLAINTS

EXPOSURE

The patient must be stripped to the waist. Preferably he should stand, or he may sit upon a stool.

STEPS IN CLINICAL EXAMINATION

A suggested routine for clinical examination of the neck is summarised in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1 Routine clinical examination in suspected disorders of the neck

| 1. LOCAL EXAMINATION OF NECK, WITH NEUROLOGICAL AND VASCULAR SURVEY OF UPPER LIMBS | |

| Inspection | Movements |

| Bone contours: ?deformity | Flexion–extension |

| Soft-tissue contours | Lateral flexion |

| Colour and texture of skin | Rotation |

| Scars or sinuses | ? Pain on movement |

| Palpation | ? Crepitation on movement |

| Skin temperature | Neurological state of upper limb |

| Bone contours | Muscular system |

| Soft-tissue contours | Sensory system |

| Local tenderness | Sweating |

| Vascular state of upper limb | Reflexes |

| Colour | |

| Temperature | |

| Pulses | |

| 2. EXAMINATION OF POTENTIAL EXTRINSIC SOURCES OF NECK SYMPTOMS | |

| Symptoms suggestive of a neck disorder may arise from the ears or throat. Symptoms in the upper limb suggesting a neck disorder with involvement of the brachial plexus may arise from shoulder, elbow, or nerve trunks in their peripheral course | |

| 3. GENERAL EXAMINATION | |

| General survey of other parts of the body. Neck symptoms may be only one manifestation of a more widespread disease | |

DEFORMITY

The cervical spine normally has a slight anterior curvature (lordosis). Straightening of this curve, or an angulation in the reverse direction (kyphosis), is sometimes significant and may suggest an underlying abnormality. Any lateral or rotational deformity (torticollis) must also be noted.

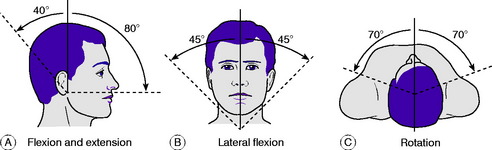

MOVEMENTS

The movements to be examined are flexion, extension, lateral flexion to right and left, and rotation to right and left (Fig. 12.1). Flexion–extension movements occur mainly at the occipito-atlantoid joint but to some extent throughout the cervical spine. Lateral flexion takes place throughout the cervical spine. Rotation occurs largely at the atlanto-axial joint, with a small range of movement at the other joints. It is important to find out whether movement causes pain and, if so, whether the pain is felt locally in the neck or whether it is referred down the upper limbs. It should be noted also whether movement is accompanied by audible or palpable crepitation.

NEUROLOGICAL EXAMINATION OF UPPER LIMBS

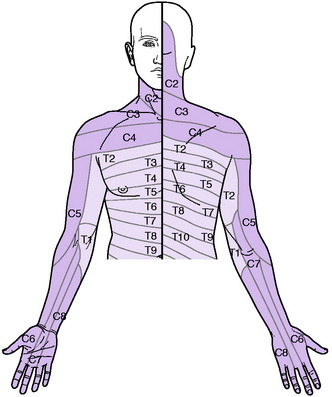

Sensory system. Examine the patient’s sensibility to touch and pin prick. In appropriate cases test also the sensibility to deep stimuli, joint position, vibration, and heat and cold. The nerve roots supplying the sensory dermatomes in the upper limb are shown in Fig. 12.2. In the assessment of sensory loss it should be remembered that the middle or long finger, representing the central axis of the limb, is innervated mainly from the seventh cervical nerve. The radial half of the hand is innervated by the proximal roots of the brachial plexus (C5, C6) whereas the ulnar half is innervated from the more distal roots (C8, T1).

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Radiographic examination. Routine radiographs of the cervical spine include an antero-posterior and a lateral projection. Additional projections are often required when it is desired to show a particular structure more clearly. For a study of the dens (odontoid process) of the axis a special antero-posterior projection is made through the open mouth. Occasionally oblique projections are required for a proper investigation of the intervertebral foramina and the facet joints, and is also valuable in revealing the size and shape of a cervical rib.

DEFORMITIES AND CERVICAL INSTABILITIES

INFANTILE TORTICOLLIS (‘Congenital’ torticollis; muscular torticollis)

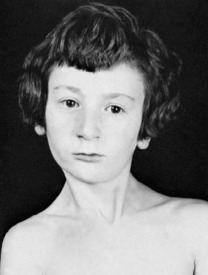

In infantile torticollis (wry neck) the head is tilted and rotated by contracture of the sternomastoid muscle of one side. Strictly this is not a true congenital deformity because it arises after birth. With improvements in obstetrical practice it is now seen much less often than it was in the past.

Clinical features. The child, often between 6 months and 3 years old when brought for consultation, is noticed to hold the head on one side. On examination, the contracted sternomastoid muscle is felt as a tight cord. The ear on the affected side is approximated to the corresponding shoulder. In long-established cases there is retarded development of the face on the affected side, with consequent asymmetry (Fig. 12.3).

CONGENITAL SHORT NECK (Klippel–Feil syndrome)

The degree of abnormality varies widely. The bony deformity consists in fusion of two or more of the cervical vertebrae. Clinically, the neck appears short or absent, and the hair-line is low. The neck may also be webbed to the shoulder. Movements of the head are restricted. Radiographs show the underlying bony abnormality, but operation is seldom indicated.

CERVICAL SUBLUXATION AND DISLOCATION (Spontaneous subluxation of the cervical spine; cervical spondylolisthesis)

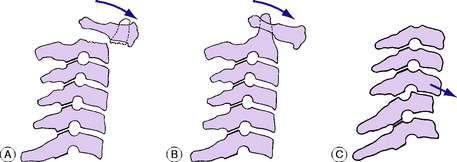

Causes and pathology. There are three types, caused by:

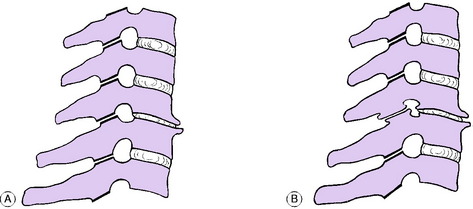

Congenital or acquired non-fusion of dens. Occasionally the dens fails to fuse with the body of the axis by bone, being attached only by fibrous tissue (os odontoideum). Under the constant stress of superimposed weight the fibrous bond slowly stretches, allowing the dens, and with it the atlas and skull, to slide gradually forwards upon the axis (Fig. 12.4A). A similar condition may exist after fracture of the dens, but this would be preceded by a history of trauma. Instability may also be present in patients with Down’s syndrome and radiological screening may be indicated in patients with this condition.

Inflammatory softening of the transverse ligament of the atlas. In this type the underlying cause is an inflammatory lesion in the upper part of the neck, such as rheumatoid arthritis or a severe local infection of the throat or glands. There is rarefaction of the atlas, with softening of the transverse ligament. In consequence the atlas is able to slide forwards upon the axis (Fig. 12.4B).

Instability from previous injury or from arthritis. A traumatic fracture- dislocation or subluxation at any level in the cervical spine may cause permanent instability, with a liability to slow redisplacement months or years after the initial injury (Fig. 12.4C).

Clinical features. In the inflammatory type there is complaint of ‘stiff neck’. The head is held rigidly, the cervical muscles being in spasm. In subluxation from congenital or post-traumatic instability there are discomfort and stiffness in the neck, and flexion deformity is apparent. Radiographs will show the displacement, its level and its type (Fig. 12.5).

Congenital or post-traumatic instability. If subluxation is not complicated by neurological disturbance, treatment may be expectant (observation only), by a plastic collar to give support, or by local fusion of the spine, according to the severity of the displacement and of the local symptoms. If neurological disturbance is present, treatment is by preliminary skull traction to reduce the displacement, followed by operative fusion of the affected segments of the spine.

TUBERCULOSIS OF THE CERVICAL SPINE (Tuberculous cervical spondylitis)

Tuberculosis is far less common in the cervical spine than in the thoracic and lumbar regions. It is now seldom seen in Britain, but it still occurs commonly in Africa and in Eastern countries. The general features of tuberculosis of bone were described in Chapter 7p. 92.

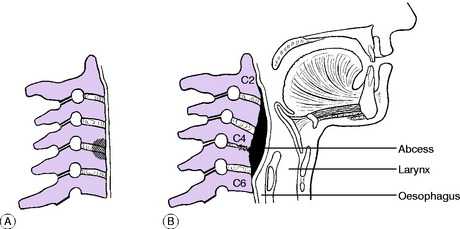

Pathology. The infection begins in the front of a vertebral body, or in an intervertebral disc (Fig. 12.6A). Destruction of bone and intervertebral disc leads to anterior collapse with consequent cervical kyphosis (Fig. 12.6B). The degree of destruction varies widely, depending upon the virulence of the organism and the resistance of the patient. Formation of pus leads either to a retropharyngeal abscess (behind the prevertebral fascia), which may eventually point at the posterior margin of the sternomastoid muscle, or, if the pus tracks posteriorly, to a suboccipital abscess. The spinal cord may be damaged by direct pressure of an abscess, or by secondary thrombosis of the vessels of the cord.

Imaging. Radiographs always show diminution of disc space, usually some destruction of bone (Fig. 12.6B), and sometimes an abscess shadow. MRI scans will provide more detailed information on the extent of the soft tissue abscess and assist in planning surgical drainage.

Diagnosis. Important diagnostic features are the history of tuberculous contact or disease, spasm of the neck muscles with restriction of all movements, abscess formation, and the radiographic findings.

Treatment. The principles of treatment are the same as for other forms of skeletal tuberculosis. Antibacterial therapy: combinations of antituberculous drugs were described on page 102. Local treatment is by support for the cervical spine by a halo splint or by a plastic collar until the disease is quiescent – often a matter of several months.

Operation is sometimes required and the following are the main indications:

PYOGENIC INFECTION OF THE CERVICAL SPINE (Pyogenic cervical spondylitis)

Clinical features. The onset is usually acute or subacute, with pyrexia. The clinical features resemble those of tuberculous spondylitis (p. 192), but the course is more rapid. A suppurative process elsewhere in the body (for instance, in the pharynx or pelvis) is usually present. Radiographs show local osteoporosis or erosion of bone, diminution of disc space, and sometimes subligamentous new bone formation.

Treatment. Appropriate antibiotic drugs (see p. 89) should be given systemically. The cervical spine must be immobilised in a rigid collar or brace; sometimes sustained head traction with a halo splint is required for relief of spasm. When there is an abscess it should be drained, especially if the spinal cord is threatened. Spontaneous fusion of the affected vertebrae usually makes operative fusion unnecessary.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS (General description of rheumatoid arthritis, p. 134)

The cervical spine is the third most commonly affected in rheumatoid polyarthritis, after the hands and feet. In sero-positive disease up to 50% will show evidence of destructive synovitis in the vertebral joints. It is important that this be recognised, because there is a risk that destruction of the intervertebral joints may allow gradual forward subluxation of a cervical vertebra upon the one next below it, with danger to the integrity of the spinal cord. There is a particular risk of subluxation at the atlanto-axial joint due to softening of the transverse ligament of the atlas (see Fig. 12.5). Destructive changes may also occur at multiple levels below the axis vertebra and may result in subluxation causing progressive spinal cord or nerve root compression. It is important to remember that these destructive changes may occur insidiously without significant symptoms because of the involvement of the upper and lower limb joints; thus they may be overlooked until the onset of paralysis.

ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS

Ankylosing spondylitis is a disease that creeps up the spine from below having originated in the sacro-iliac joints and the lumbar spine. In a high proportion of cases – though by no means in all – it extends to involve the cervical region, with aching pain and permanent stiffness – sometimes total rigid ankylosis – of the intervertebral joints. Very occasionally the neck may become ankylosed in an extreme degree of flexion producing a ‘chin on chest’ deformity. When this interferes with swallowing and the ability to see ahead it may justify surgical correction by osteotomy and fusion. This is very high-risk surgery with a 20% mortality rate and should only be undertaken in specialised centres by surgeons with the necessary skills. The disease of ankylosing spondylitis as a whole will be described in Chapter 13 (p. 229).

CERVICAL SPONDYLOSIS (Cervical spondylarthritis; cervical spondylarthrosis; cervical osteoarthritis; cervical osteoarthrosis)

Cause. The primary degenerative changes may be initiated by injury, but usually the condition is simply a manifestation of normal ageing processes.

Pathology. Degenerative arthritis occurs most commonly in the lowest three cervical joints. The changes affect first the central intervertebral joints (between the vertebral bodies) and later the posterior intervertebral (facet) joints. In the central joints there is degenerative narrowing of the intervertebral disc, and bone reaction at the joint margins leads to the formation of osteophytes (Fig. 12.7A). In the posterior intervertebral joints the changes are those of osteoarthritis in any diarthrodial joint – namely, wearing away of the articular cartilage and the formation of osteophytes (spurs) at the joint margins (Fig. 12.7B).

Secondary effects. Osteophytes commonly encroach upon the intervertebral foramina, reducing the space for transmission of the cervical nerves (Fig. 12.7B). If the restricted space in a foramen is reduced still further by traumatic oedema of the contained soft tissues, manifestations of nerve pressure are likely to occur. Exceptionally, the spinal cord itself may suffer damage from encroachment of osteophytes within the spinal canal.

Clinical features. The symptoms are in the neck or in the upper limb, or both.

On examination, the neck may be slightly kyphotic. The posterior cervical muscles may be somewhat tender but they are not in spasm. Movements are not markedly diminished except during acute exacerbations or when the degenerative changes are very advanced. Audible crepitation on movement is common. In the upper limb objective findings are usually slight or absent, for nerve pressure is seldom great enough to produce well-defined objective neurological signs (compare prolapsed intervertebral disc). Thus demonstrable motor weakness or sensory impairment is exceptional. Depression of one or more of the tendon reflexes is, however, fairly common.

Radiographic features. There is narrowing of the intervertebral disc space, with formation of osteophytes at the vertebral margins, especially anteriorly (Fig. 12.8A). A single vertebral level may be affected – often at the C5–C6 or C6–C7 level – or there may be changes at more than one level. Encroachment of osteophytes upon an intervertebral foramen is demonstrated best in oblique projections (Fig. 12.8B) or on CT scans. In a few patients with clinical evidence of neurological impairment MRI scanning may be indicated to identify nerve root or cord compression.

Diagnosis. Distinction has to be made from:

Treatment. There is a strong tendency for the symptoms of cervical spondylosis to subside spontaneously, though they may persist for many weeks and the structural changes are clearly permanent. Treatment is thus aimed towards assisting natural resolution of temporarily inflamed or oedematous soft tissues. In mild cases such measures include anti-inflammatory analgesic drugs and muscle relaxants as well as various forms of physiotherapy. Ultrasound, short-wave diathermy, massage, and intermittent traction have all been used, but none have been shown to be effective in large clinical trials. Some benefit has been shown for mobilisation and strengthening exercises. Manipulation is sometimes recommended, but in the presence of extensive osteophytes it is hazardous because it may damage the spinal cord; it should therefore be employed with extreme caution, and only by those familiar with a gentle technique. In the more severe cases it is wise to provide rest and support for the neck by a closely fitting protective cervical collar (Fig. 12.10A), but this should only be worn for a few weeks until the acute symptoms subside to prevent atrophy of the spinal muscles.

PROLAPSED CERVICAL DISC

Displacement of intervertebral disc material in the cervical spine is much less common than it is in the lumbar region. It is characterised by pain and stiffness in the neck, often with neurological manifestations in the upper limb and occasionally with signs of spinal cord compression.

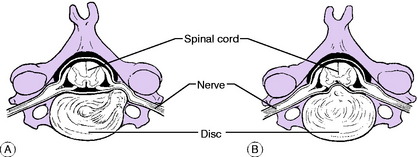

Pathology. The disc between C5–C6 and that between C6–C7 are those most frequently affected. Part of the gelatinous nucleus pulposus protrudes through a rent in the annulus fibrosus at its weakest part, which is postero-lateral; or part of the annulus itself may be displaced. If slight, the protrusion bulges against the pain-sensitive posterior longitudinal ligament, causing local pain in the neck. If large, the protrusion herniates through the ligament and may impinge upon the nerve leaving the spinal canal at that level (postero- lateral prolapse) (Fig. 12.11A), or occasionally upon the spinal cord itself (central prolapse) (Fig. 12.11B). Healing is probably by shrinkage and fibrosis of the extruded material rather than by its reposition within the disc. Secondary effects: Prolapse of a disc accelerates its degeneration and predisposes to the development of osteoarthritis (cervical spondylosis) in later years.

Clinical features. Central protrusions. These lead to manifestations of spinal cord compression and may be confused with spinal cord tumours or other central neurological disorders. They fall within the province of the neurosurgeon rather than the orthopaedic surgeon.

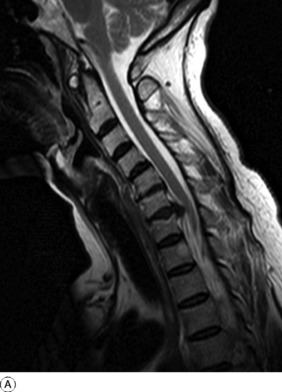

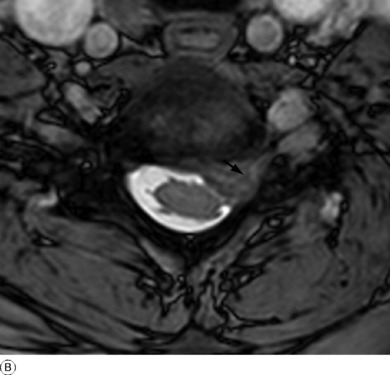

Imaging. Radiographs characteristically show a normal appearance in the first attack, but narrowing of one of the disc spaces (usually C5–C6 or C6–C7), denoting long-standing disc degeneration, is often demonstrable. Magnetic resonance imaging may show the displaced disc material and its relationship to the nerve roots and cord (Fig. 12.12).

Fig 12.12 A and B Sagittal and axial MR scans showing a posterior cervical disc protrusion at the C6–C7 level. On the axial scan B the disc material is seen lying on the left side of the canal extending into the exit foramen (arrow) and compressing the underlying C6 nerve root.

Diagnosis. Prolapsed cervical disc has to be differentiated:

The main conditions that may be confused with it are the same as those listed in the differential diagnosis of cervical spondylosis (p. 196). A confident diagnosis is justified only when a suggestive history is associated with the signs of a lesion of a single cervical nerve, and provided always that other possible causes have been excluded by careful investigation.

Relationship between prolapsed disc and cervical spondylosis

Treatment. This depends upon the nature and severity of the individual case. When the symptoms are slight no treatment other than perhaps a mild analgesic drug is required. In the more severe cases treatment is advisable, especially in the early acute stage. If the neck is ‘stiff’ and if movements aggravate the neck and limb pain, rest for a few weeks in a supportive collar made from heat-moulded reinforced plastic or a more rigid adjustable orthosis (Fig. 12.10) is the most satisfactory method. Pain is usually severe, necessitating fairly intensive analgesic therapy. As the acute symptoms gradually subside, physiotherapy in the form of graduated neck exercises to restore full mobility and muscle strength is often helpful.

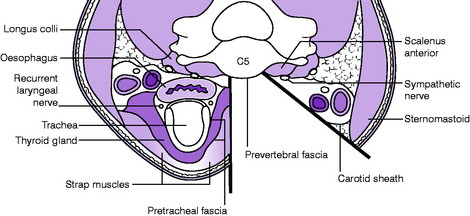

In cases of intractable radicular pain or myelopathy surgical treatment may be required. Removal of the affected degenerative disc material can be achieved through an antero-lateral approach to the vertebral bodies (Fig. 12.13). This displaces the sterno-mastoid muscle and contents of the carotid sheath laterally, with the strap muscles, trachea and oesophagus moved medially to expose the pre-vertebral fascia. It is important to confirm the correct intervertebral space with intra-operative radiography before disc removal. Distraction of the vertebral bodies facilitates removal of the disc and the space created is then filled with a block of autogenous cortico-cancellous bone graft to produce an anterior interbody fusion. The technique can also be applied to disc degeneration at more than one level by the use of a longer strut graft (see Fig. 4.4A), usually reinforced with a plate and screws. Postoperatively the neck is immobilised in a light collar until there is radiological evidence of bone healing.

CERVICAL RIB

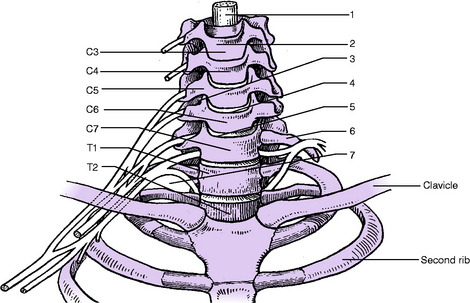

Radiographic features. Radiographs show the abnormal rib: if small, it is seen best in oblique projections (Fig. 12.14). In cases of suspected vascular obstruction arteriography is required.

The diagnosis of symptomatic cervical rib depends upon the detection of the characteristic neurological signs or vascular disturbance in association with a demonstrable supernumerary rib. Prolapsed intervertebral disc at C7–T1 gives a similar clinical picture neurologically, and indeed it may often be the true cause of symptoms ascribed to a cervical rib; but in prolapsed disc there is a strong tendency to natural recovery, which is not the case with cervical rib. Arteriography may be conclusive by revealing obstruction of the subclavian artery.

SCALENUS SYNDROME (First rib syndrome; thoracic outlet syndrome)

Occasionally the neurological manifestations characteristic of cervical rib occur in the absence of a demonstrable skeletal abnormality. They have been ascribed to trapping of nerves between the first rib and the clavicle (costo-clavicular compression), or between the first rib and the scalenus anterior muscle; and to stretching of the lowest trunk of the brachial plexus over the normal first rib. More often, they are caused by a tough fibrous band in the scalenus medius muscle, which may lead to kinking of the lowest trunk of the brachial plexus, demonstrable at operation. The symptoms are easily confused with those from a prolapsed intervertebral disc between C7 and T1. Treatment should be conservative at first, as for prolapsed disc. Gradual improvement would support the diagnosis of disc prolapse. But if the symptoms persist with undiminished intensity for a long time a true scalenus syndrome is probably the cause. In that event it may be justifiable to explore the plexus, to divide the scalenus anterior and the scalenus medius, and if necessary to excise the first rib.

TUMOURS IN RELATION TO THE CERVICAL SPINE AND EMERGING NERVES

Tumours involving the cervical spine or the related nerves may arise:

Destruction and collapse of cervical vertebrae. The commonest cause is a metastatic carcinoma (Fig. 12.15). The clinical features are local pain and, usually, flexion deformity. The spinal cord or the issuing cervical nerves may be involved, with corresponding signs of spinal cord compression or peripheral nerve defect.

Spinal cord compression. Interference with the function of the spinal cord may be caused by tumours of the cord itself or of its meninges, by tumours of nerves (neurofibroma), or by tumours of the bony spinal column. The clinical manifestations depend upon the location of the tumour. Typically, root pain at the level of the lesion is followed by lower motor neurone changes at the same level and by progressive upper motor neurone paralysis and visceral dysfunction below the lesion.

Interference with the brachial plexus. Nerves forming the brachial plexus may be involved by tumours of the nerves themselves (neurofibroma), by bone tumours, or by tumours at the thoracic inlet (Fig. 12.16). The predominant features are severe pain along the course of the nerve or nerves affected (neck or upper limb) and increasing motor and sensory impairment in the distribution of the nerves.

Imaging. Plain radiographs will usually help in discovering a tumour arising in the bones of the spinal column or eroding the bones from outside (Fig. 12.15). They may also reveal a tumour at the thoracic inlet (Fig. 12.16). Computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may give more precise information. Radiographs of the chest may reveal an apical lung tumour or pulmonary metastases.