34 Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting are commonly (but not universally) associated symptoms. The word nausea is derived from the Greek nautia, meaning sea-sickness, while vomiting is derived from the Latin vomere, meaning to discharge. Nausea is a subjective sensation whereas vomiting is the reflex physical act of expulsion of gastric contents. Retching is defined as ‘spasmodic respiratory movements’ against a closed glottis with contractions of the abdominal musculature without expulsion of any gastric contents, that is, ‘dry heaves’ (American Gastroenterological Association, 2001). It is important to differentiate vomiting from regurgitation, rumination and bulimia. Regurgitation is the return of oesophageal or gastric contents into the hypopharynx with little effort. Rumination is the passive regurgitation of recently ingested food into the mouth followed by re-chewing, re-swallowing or spitting out. It is not preceded by nausea and does not include the various physical phenomena associated with vomiting. Bulimia involves overeating followed by self-induced vomiting.

Epidemiology

Nausea and vomiting from all causes have significant associated social and economic costs in terms of loss of productivity and extra medical care. In the community, nausea (with or without vomiting) is most likely to be associated with infection, particularly gastro-intestinal infection. Vestibular disorders may cause vomiting as can motion sickness. Nausea and vomiting may be associated with pain, for example, migraine and severe cardiac pain. Many medicines also cause nausea and occasionally vomiting as a common dose-related (Type A) adverse effect. This is particularly common with opioid use in palliative care. Nausea and vomiting also occur post-operatively or in association with cytotoxic chemotherapy, or radiotherapy. These and other causes of nausea and vomiting are listed in Table 34.1.

| Central | |

|---|---|

| i. Intracranial | Migraine |

| Raised intracranial pressure (tumour, infection, haemorrhage, hydocephalus, etc.) | |

| ii. Labyrinthine Iatrogenic | Labyrinthitis, motion sickness, Ménière’s disease, otitis media |

| Cancer chemotherapy | |

| Many other medicines (e.g. opioids) | |

| Radiotherapy | |

| Post-operative | |

| Endocrine/ metabolic | Pregnancy, uraemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, Addison’s disease, acute intermittent porpyhria |

| Infectious | Gastroenteritis (viral or bacterial) |

| Other infections elsewhere | |

| Gastro-intestinal disorders | Mechanical obstruction (gastric outlet or small bowel) |

| Organic gastro-intestinal disorders (e.g. cholecystitis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, etc.) | |

| Functional gastro-intestinal disorders (e.g. non-ulcer dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome, etc.) | |

| Psychogenic disorders | Psychogenic vomiting, anxiety, depression |

| Pain related | Myocardial infarction |

(adapted from Quigley et al., 2001)

Pathophysiology

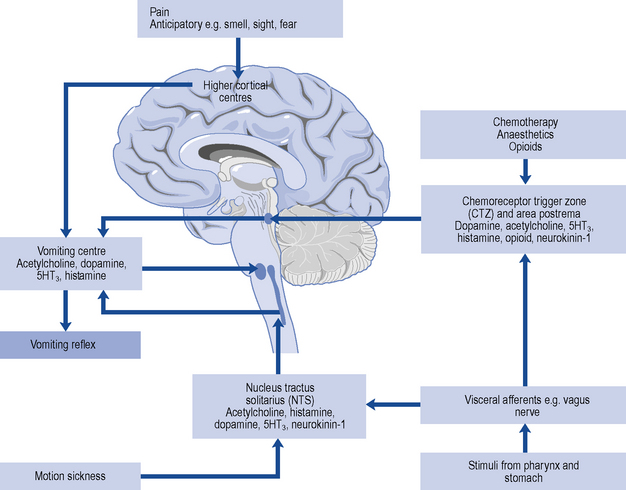

The vomiting centre is situated in the dorsolateral reticular formation close to the respiratory centre and receives impulses from higher centres, visceral efferents, the eighth (auditory) nerve (the latter two through the nucleus tractus solitarius) and from the CTZ (Fig. 34.1). It includes a number of brainstem nuclei required to integrate the responses of the gastro-intestinal tract, pharyngeal muscles, respiratory muscles and somatic muscles to result in a vomiting episode. The vomiting centre may be stimulated in association with, or in isolation from, the nausea process.

Patient management

Management of the patient with nausea and vomiting is approached in three steps.

Some scenarios illustrating common therapeutic problems in the management of nausea and vomiting are outlined in Table 34.2.

Table 34.2 Common therapeutic problems in managing patients with nausea and vomiting

| Problem | Possible cause/solution |

|---|---|

| Persistent nausea and vomiting despite treatment | Is the cause correctly diagnosed? |

| Review the antiemetic agent and the dose: if both correct, change to or add a second agent | |

| Patient with PONV is vomiting despite suitable antiemetic regimen | Check analgesia: pain may be causing nausea and vomiting, or patient-controlled analgesia may require adjustment downwards to reduce analgesic dose |

| Patient with bowel obstruction is passing flatus | Prokinetic drug is first-choice antiemetic. 5HT3 antagonists may also be effective |

| Patient with bowel obstruction is not passing flatus | Spasmolytic drug is first choice. Prokinetic drugs are contraindicated. Similarly, bulk-forming, osmotic and stimulant laxatives are inappropriate; phosphate enemas and faecal softeners are better |

| A terminally ill patient receiving diamorphine is vomiting, despite use of haloperidol | Levomepromazine given as a 24-h subcutaneous infusion can be very effective |

| A patient with renal failure (uraemia) is vomiting | Consider a 5HT3 antagonist |

| A patient develops an acute dystonic reaction to metoclopramide | Give an intramuscular injection of an antihistamine. Such extrapyramidal reactions to metoclopramide are more common in young adults (especially females) and this agent is best avoided in this group |

PONV, post-operative nausea and vomiting.

Antiemetic drugs

Complementary and alternative medicines

Systematic reviews support the use of stimulating wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing PONV in combination with, or as an alternative to, conventional antiemetics (Lee and Done, 2004). A systematic review of randomised trials has also demonstrated the efficacy of ginger (at least 1 g preoperatively) in PONV. Ginger has also been claimed to be beneficial in motion sickness and pregnancy-associated nausea, but the evidence for each is limited to single randomised trials (Ernst and Pittler, 2000).

Drug treatment in selected circumstances

Post-operative nausea and vomiting

Around 25% of patients experience PONV within 24 h of surgery (Gan et al., 2003). The aetiology is complex and multifactorial and includes patient-, medical-, surgical- and anaesthetic-related factors. Management is multimodal and involves strategies to reduce baseline risk such as using less emetogenic induction agents, anaesthetic agents and analgesics, consideration of the use of regional rather than general anaesthesia, adequate hydration and intraoperative supplemental oxygen use and avoidance of high-dose neostigmine.

Risk scores

Prophylaxis is preferable to treatment and this can often be achieved not only by use of antiemetic drugs but also by suitable planning. For example, not all patients undergoing surgery will experience post-operative nausea and vomiting and universal prophylaxis is not cost-effective (Habib and Gan, 2004). A simple risk scoring system has been devised in which the score increases relative to the presence or absence of four factors:

The incidence of post-operative nausea and vomiting with the presence of none, one, two, three or all four of these risk factors has been shown to be 10%, 20%, 40%, 60% and 80%, respectively (Apfel et al., 1999). Use of risk scores based on these criteria helps to appropriately tailor antiemetic use and can significantly reduce the incidence of nausea and vomiting in clinical practice (Apfel et al., 2002; Pierre et al., 2004).

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting

Management of CINV depends on the emetogenicity of the chemotherapy regimen and the use of combinations of antiemetic drugs based on their varying target receptors. Chemotherapy agents are divided into four emetogenic levels (Table 34.3) defined by expected frequency of emesis (Kris et al., 2006).

| Emetic risk (incidence of emesis without antiemetics) | Agent |

|---|---|

| High (>90%) | Cisplatin |

| Mechlorethamine | |

| Streptozotocin | |

| Cyclophosphamide ≥1500 mg/m2 | |

| Carmustine | |

| Dacarbazine | |

| Dactinomycin | |

| Moderate (30–90%) | Oxaliplatin |

| Cytarabine >1000 mg/m2 | |

| Carboplatin | |

| Ifosfamide | |

| Cyclophosphamide <1500 mg/m2 | |

| Doxorubicin | |

| Daunorubicin | |

| Epirubicin | |

| Idarubicin | |

| Irinotecan | |

| Low (10–30%) | Paclitaxel |

| Docetaxel | |

| Mitoxantrone | |

| Topotecan | |

| Etoposide | |

| Pemetrexed | |

| Methotrexate | |

| Mitomycin | |

| Gemcitabine | |

| Cytarabine ≤1000 mg/m2 | |

| Flurouracil | |

| Bortezomib | |

| Cetuximab | |

| Trastuzumab | |

| Minimal (<10%) | Bevacizumab |

| Bleomycin | |

| Busulfan | |

| 2-Chlorodeoxyadenosine | |

| Fludarabine | |

| Rituximab | |

| Vinblastine | |

| Vincristine | |

| Vinrelbine |

(from Kris et al., 2006)

In high-level acute emesis, a single dose of a 5HT3 antagonist given before chemotherapy is therapeutically equivalent to a multidose regimen with these agents. Odansetron and granisetron appear to be equally effective in CINV and only one study suggests palonosetron is superior to granisetron when given in combination with dexametasone (Billio et al., 2010). Oral formulations of antiemetics are often as effective as intravenous ones. In lower level acute emesis, the cost of the 5HT3 antagonists is prohibitive and metoclopramide or prochlorperazine are commonly used and are sufficiently effective.

When apparently appropriate antiemesis regimens fail, consideration should be given to the possibility of other underlying disease- and medication-related issues (Box 34.1).

Pregnancy-associated nausea and vomiting

In first-trimester nausea and vomiting, simple measures such as small frequent carbohydrate-rich meals and reassurance are sufficient to control symptoms. Ginger and P6 acupressure have also been advocated, although the evidence base is equivocal in early pregnancy (Jewell and Young, 2003). More recent studies on the use of acupuncture in pregnancy-associated nausea and vomiting remain unclear (King and Murphy, 2009). It is important to avoid antiemetic drugs when possible, but promethazine has been recommended in severe vomiting, with prochorperazine or metoclopramide as second line agents. In Canada and the USA, a combination of pyridoxine (vitamin B6) and an antihistamine (doxylamine) is approved for the treatment of nausea in pregnancy but this combination treatment appears to be less effective for controlling vomiting.

In the serious condition of hyperemesis gravidarum, drug therapy may be used, although no trials have shown clear benefit (Jewell and Young, 2003). Fluid and electrolyte replacement, rest and if necessary postpyloric or parenteral feeding to provide nutritional support and vitamins (e.g. thiamine to reduce the risk of Wernicke’s encephalopathy) supplementation should be considered. There are few safety or efficacy data on which to select the most appropriate treatments so the agents recommended for vomiting of pregnancy mentioned above are generally used in the first instance in the UK.

Migraine

Motion sickness

The anticholinergic agent hyoscine is the prophylactic drug of choice, although there is no evidence of its benefit once motion sickness is established (Spinks et al., 2004). Antihistamine drugs may also be effective. The less sedating antihistamines cinnarizine or cyclizine are used. Promethazine, an antihistamine with sedative effects, is also effective but phenothiazines, domperidone, metoclopramide and 5HT3-receptor antagonists appear to be ineffective in this situation. Treatment should be started before travel; for long journeys, promethazine or transdermal hyoscine may be preferred for their longer duration (24 h and 3 days, respectively). Otherwise, repeated doses will be needed.

Drug-associated nausea and vomiting

As well as chemotherapeutic agents, many commonly used medications for other disorders can cause nausea and vomiting (Quigley et al., 2001). Opioids are perhaps the most important group clinically, but dopamine agonists (used in Parkinson’s disease), theophylline, digoxin and macrolide antibiotics such as erythromycin can all cause nausea and/or vomiting, often in a dose-related manner (Type A toxicity). High-dose oestrogen, used in postcoital contraception, can produce these symptoms. Consideration should be given to altering the dose of the offending agent when possible, and administering the medication with food. With some agents, tolerance may develop. Thus, tolerance to the emetic effects of opioids often develops within 5–10 days and, therefore, antiemetic therapy is not generally needed for long-term opioid use.

Palliative care-associated nausea and vomiting

It is important to determine the predominant underlying cause for patients’ symptoms by taking a careful history, examination and appropriate investigations so that potentially reversible causes of nausea and vomiting can be treated (Box 34.2) and the most suitable antiemetic prescribed.

Conclusion

Case 34.1

A 30-year-old man presents seeking a remedy for vomiting which had an acute onset, 12 h previously.

Question

What questions should be asked to determine the nature, cause and seriousness of these symptoms?

Answer

Answer

American Gastroenterological Association. AGA medical position statement: nausea and vomiting. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:261-262.

Apfel C.C., Laara E., Koivuranta M., et al. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:693-700.

Apfel C.C., Kranke P., Eberhart L.H., et al. Comparison of predictive models for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br. J. Anaesth.. 2002;88:234-240.

Billio A., Morello E., Clarke M.J. Serotonin receptor antagonists for highly emetogenic chemotherapy in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (1):2010. Art. No.: CD006272.pub2. doi: 10.1002/14651858. Available at: http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab006272.html

Ernst E., Pittler M.H. Efficacy of ginger for nausea and vomiting: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Br. J. Anaesth.. 2000;84:367-371.

Gan T.J., Meyer T., Apfell C.C., et al. Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth. Analg.. 2003;97:62-71.

Habib A., Gan T.J. Evidence-based management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a review. Can. J. Anaesth.. 2004;51:326-341.

Jewell D., Young G. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (4):2003. Art. No.: CD000145. doi: 10.1002/14651858

King T.L., Murphy P.A. Evidence-based approaches to managing nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;54:430-444.

Kris M.G., Hesketh P.J., Somerfield M.R., et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline for antiemetics in oncology: update. J. Clin. Oncol.. 2006;24:2932-2947.

Lee A., Done M.L. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (3):2004. Art. No.: CD003281. doi: 10.1002/14651858

Pierre S., Corno G., Benais H., et al. A risk score-dependent antiemetic approach effectively reduces postoperative nausea and vomiting – a continuous quality improvement initiative. Can. J. Anaesth.. 2004;51:320-325.

Quigley E.M., Hasler W.L., Parkman H.P. A technical review on nausea and vomiting. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:263-268.

Spinks A.B., Wasiak J., Villanueva E.V., et al. Scopolamine for preventing and treating motion sickness. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (3):2004. Art No CD002851

Berger A. Prevention of Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and vomiting. New York: PRRR Inc; 2004.

Gan T.J. Risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth. Analg.. 2006;102:1884-1898.

Hatfield A., Tronson M., editors. The Complete Recovery Room, fourth ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Mannix K. Palliation of nausea and vomiting in malignancy. Clin. Med.. 2006;6:144-147.

Spinks A., Wasiak J., Bernath V., Villanueva E. Scopolamine (hyoscine) for preventing and treating motion sickness. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (3):2007. Art. No.: CD002851. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002851.pub3 Available at: http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab002851.html